Translate this page into:

Psoriatic alopecia - fact or fiction? A clinicohistopathologic reappraisal

2 Department of Dermatopathology Section, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

Correspondence Address:

Meera Mahalingam

Dermatopathology Section, Department of Dermatology, Boston University School of Medicine,609 Albany Street, J-301, Boston, MA 02118

USA

| How to cite this article: Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, Mahalingam M. Psoriatic alopecia - fact or fiction? A clinicohistopathologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:611-619 |

Abstract

Background: The incidence of psoriatic alopecia in psoriatic patients is underwhelming, given the prevalence of psoriasis in the North American population. Recently, a 60-year-old Albanian female, lacking a significant medical history for psoriasis, presented to our clinic with a 1-year history of "dandruff" associated with itch, hair thinning, and histopathologic evidence consistent with prior reports of "psoriatic alopecia." Aims: The absence of preceding or concomitant psoriasis suggests that the patient's alopecia is an antecedent manifestation of psoriasis, thus prompting this retrospective study to ascertain better the relationship between alopecia and psoriasis. Methods: We performed a retrospective review of 33 scalp biopsies on 31 patients having histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis belonging to 31 patients seen between 2007 and 2010. Results: Alopecia was a presenting feature in 48% of cases with definitive clinical and/or histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis (scale crust with neutrophils, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and hypogranulosis). The most common follicular-related changes were infundibular dilatation (87%) followed by perifollicular fibrosis (77%), perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation (68%), thinning of the follicular infundibulum (55%), and fibrous tracts (28%). Of interest, sebaceous glands were absent in 60% and atrophic in 25% of cases. Conclusion: While a major limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective one, given that these changes are common to varying degrees in all lymphocytic scarring alopecias, we posit that psoriatic alopecia likely represents a secondary clinical change to a primary process and is not a unique histopathologic entity. A prospective study with a control group that includes lymphocytic scarring alopecias from non-psoriatic patients is required to support our findings.Introduction

Although psoriasis is fairly common in the North American population with an incidence of 1.5-2%, [1] a paucity of data exist regarding the characterization of psoriatic alopecia, with less than 60 cases published to date. [2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7] First described by Shuster in 1972, [2] psoriatic alopecia initially was thought to be associated exclusively with acute erythrodermic, generalized pustular psoriasis or chronic plaque psoriasis. [3],[5] Conflicting data exist as to whether the alopecia in psoriasis is a scarring or non-scarring process. While some histopathologic studies indicate a scarring process (i.e., reduction in hair follicle density and presence of a peri-infundibular lymphocytic infiltrate with destruction of the follicle), [3],[4],[5],[6],[7] clinical reports of complete hair re-growth following topical anti-psoriatic treatments favor a non-scarring process. [4],[8]

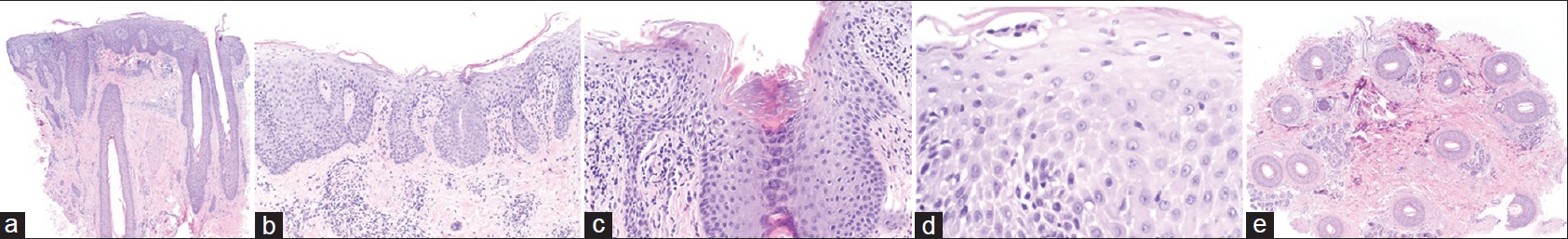

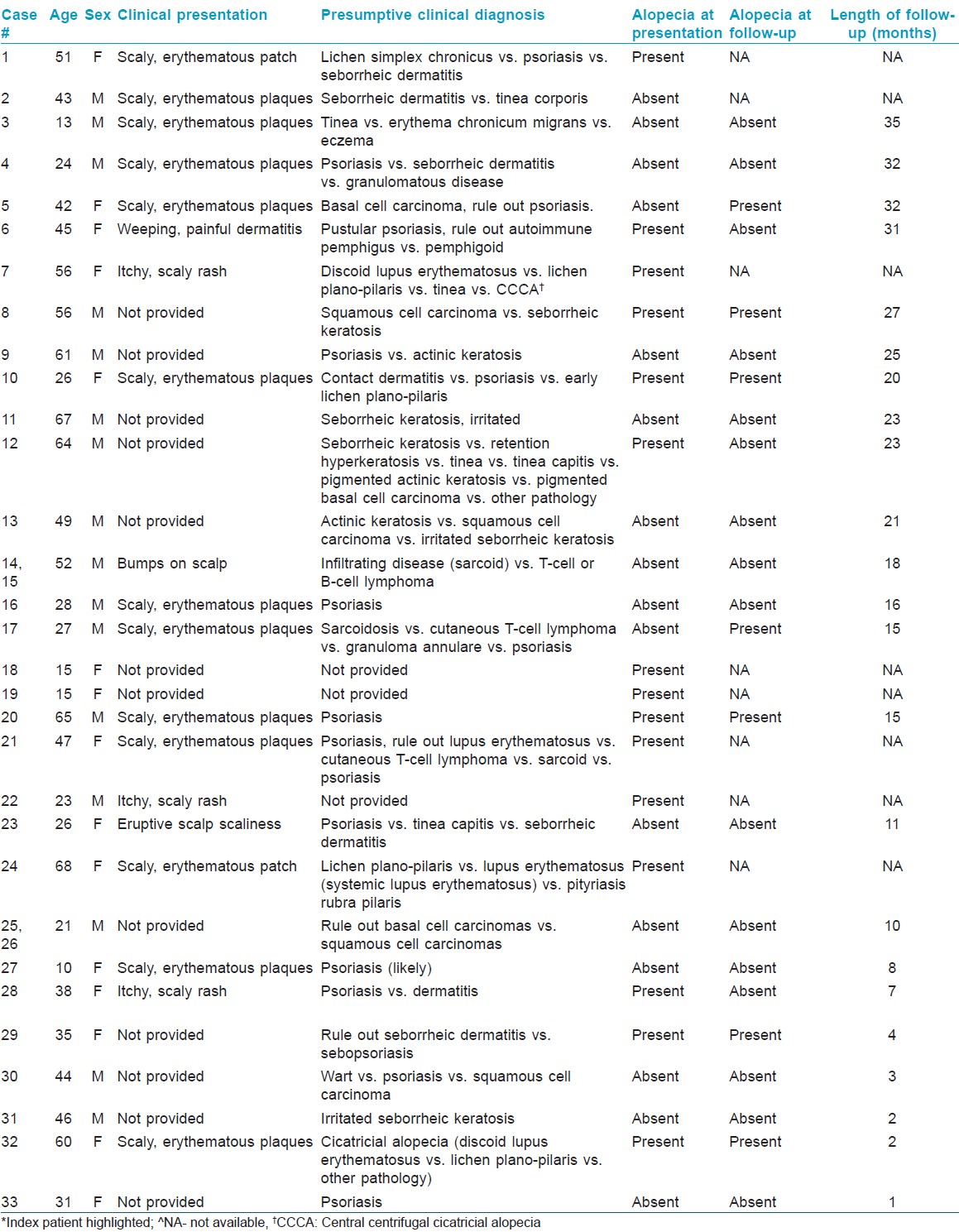

Recently, a 60-year-old Albanian female, with no current or past cutaneous manifestations of psoriasis, presented to our clinic with a 1-year history of "dandruff" associated with itch, hair thinning [Figure - 1], and histopathologic evidence consistent with prior reports of "psoriatic alopecia" [Figure - 2]a-e.

The lack of preceding or concomitant cutaneous psoriasis suggests that this patient′s alopecia is an antecedent manifestation of psoriasis, thus prompting this study to ascertain better the relationship between alopecia and psoriasis.

|

| Figure 1: Mild hair loss with fine, whitish scale and surrounding erythema on frontal scalp |

|

| Figure 2: (a-e) H and E (a-d vertical and e horizontal sections) (H and E, ×20) (a) Scanning magnification showing loss of sebaceous glands (b) Epidermal changes of confluent hypogranulosis and psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia (c) Infundibular dilatation (d) Aggregates of neutrophils in the stratum spinosum (reminiscent of spongiform pustule of Kogoj) (e) Decrease in density of hair follicles (total of 13 hair follicles seen, all in anagen) |

Methods

This study was approved by Boston University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB docket No. H- 30202). Archival materials between 2007 and 2010 of biopsies from the scalp with a histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis were retrieved from the pathology files of the Skin Pathology Laboratory,

Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA. A total of 33 cases belonging to 31 patients were identified. Histologic sections of all cases were re-reviewed, and the diagnoses confirmed by the dermatopathologist (M.M.) in all of the cases. All patient data were de- identified.

Statistical analysis

We performed comparisons of clinical characteristics and histopathologic findings on psoriasis patients with and without alopecia at presentation. Wilcoxon rank sums were used to compare means and standard deviations of age. Fisher exact test was used to compare the proportions of the presence of histopathologic features. These included both epidermal (scale crust with neutrophils, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and hypogranulosis) and follicular-related changes (absent or atrophic sebaceous gland, infundibular dilation, thinning of the follicular epithelium, perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, and fibrosis and fibrous tract formation). All statistical analyzes were performed with Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical findings

Patient demographics including indications for biopsy are summarized in [Table - 1]. The 33 cases of psoriasis occurred in 31 patients, of whom 17 (55%) were men and 14 (45%) were women. The patient ages at time of diagnosis ranged from 10 to 68 years (mean = 39.4 years). 2 of the patients had 2 biopsies done and given that both had similar clinical and histopathologic findings, will be considered as one, bringing the total number of cases to 31. Clinical presentation data was not available for 13 cases (42%). Clinical presentations included: Scaly erythematous plaque in 11/18 (62%), scaly pruritic rash in 3/18 (17%), scaly erythematous patch in 2/18 (11%), eruptive bumps in 2/18 (11%), a weeping, painful dermatitis with scale in 1/18 (6%), and eruptive scalp scaliness in 1/18 (6%). Psoriasis was the presumptive pre-biopsy diagnosis in 16/28 (57%) cases. A presumptive pre-biopsy diagnosis was unavailable for 3 cases (10%). Remarkably, 15 patients (48%), none of whom were on systemic therapy, had alopecia as a presenting symptom. None of the patients in the study were on anti-TNF-α therapy and, to the best of our knowledge, no extraneous factors were involved in patients presenting with or in those who had alopecia.

Histopathologic findings

Histopathologic findings are summarized in [Table - 2]. Overall, we observed epidermal changes consistent with psoriasis (scale crust with neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia) in all 31 (100%) cases.

Notable follicular-related changes included: infundibular dilatation in 26/30 (87%) cases, thinning of the follicular infundibulum (FI) in 17/31 (55%) cases, perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation (PFLI) in 21/31 (68%) cases, perifollicular fibrosis (PF) in 24/31 (77%) cases, and fibrous tracts in 10/28 (28%) cases. None of the cases demonstrated naked hair shafts or granulomas.

Sebaceous gland-related changes included: Complete absence in 12/20 (60%) cases and atrophy in 5/20 (25%) cases, while a normal size and number were observed in 3/20 (15%) cases. In 11/31 (35%) cases, no sebaceous glands were seen as a consequence of the biopsy type (i.e., shave biopsies).

Histopathologic findings in the follicle were limited by the type of biopsy done (i.e. shave biopsies).

Summary of statistical analyzes

Overall, no statistically significant differences were observed on histopathologic features between scalp biopsies from psoriasis patients presenting with and without alopecia [Table - 3]. All specimens exhibited epidermal changes (scale crust with neutrophils (SCN), psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia (PSEH), and hypogranulosis (HOG)) consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis. None of the biopsy specimens demonstrated naked hair shafts or had granulomas. A significantly larger proportion of patients presenting with alopecia were female (73% vs. 25%, P = 0.01). There were trends for an older age at biopsy (44.3 vs. 36.5 years, P = 0.23), more sebaceous gland abnormalities (92% vs. 63%, P = 0.25), perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (PFLI) (80% vs. 56%, P = 0.25), and presence fibrous tract (21% vs. 50%, P = 0.24), but these comparisons did not reach statistical significance. These associations remained even after correction for patients that developed alopecia on follow-up (12%, N = 2).

Discussion

Shuster first described psoriatic alopecia in 1972. [2] In this seminal article, all study patients (although not enumerated) presented concomitantly with alopecia and various types of cutaneous psoriasis. Of interest, he excluded patients with the erythrodermic and pustular forms of psoriasis, as alopecia in these 2 is well accepted. Shuster derived his data from clinical examination of hair roots plucked in bunches of 50 or more hairs. Based on his observations, he concluded that scalp psoriasis results in 3 distinct types of alopecia: 1) hair loss confined to lesional skin as confirmed by hair pluck revealing dystrophic bulbs (most common); 2) acute hair fall with a predominance of telogen hairs; and 3) "destructive or scarring alopecia" associated with decreased hair density and "perifollicular inflammation with destructional folliculitis and fibrous tissue replacement" (least common). [2] A paucity of studies on psoriatic alopecia exists (n = 7), particularly given the frequency of psoriasis in the Caucasian population. [2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] The histopathologic findings in our index case encompass the spectrum of changes described in psoriatic alopecia and include epidermal changes consistent with psoriasis, decreased hair density (totaling 13 hair follicles, predominantly in anagen), and loss of sebaceous glands. In contrast to prior studies in which patients with a known history of psoriasis presented with alopecia, [2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] our index case presented with alopecia without a definitive history of psoriasis. In our retrospective review, alopecia was a presenting feature in 45% (14 of 31) of patients identified by definitive clinical and/or histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis. Observed histopathologic changes included traditional epidermal changes of psoriasis and follicular-related changes (infundibular dilatation, perifollicular inflammation and fibrosis, thinned follicular epithelium, and fibrous tracts).

First, we questioned whether there is difference in the clinical and histopathologic findings of those patients who presented with alopecia from those who did not have alopecia at presentation. A significantly larger proportion of patients with alopecia were female (P = 0.01). No statistically significant differences were observed from the scalp biopsies between the 2 groups although a trend was observed for an older age at biopsy (44.3 vs. 36.5 years, P = 0.23), more sebaceous gland abnormalities (92% vs. 63%,P = 0.25), perifollicular infiltrates (80% vs. 56%, P = 0.25), and less fibrosis tract formation (21% vs. 50%, P = 0.24), but these comparisons did not reach statistical significance. These associations remain even after correcting for patients that developed alopecia on follow-up (12%, N = 2). Of interest, and a clinical trend that was statistically significant was that, females tend to present earlier than males - a feature that can perhaps be attributed to increased concern and sensitivity to hair loss in females compared to males.

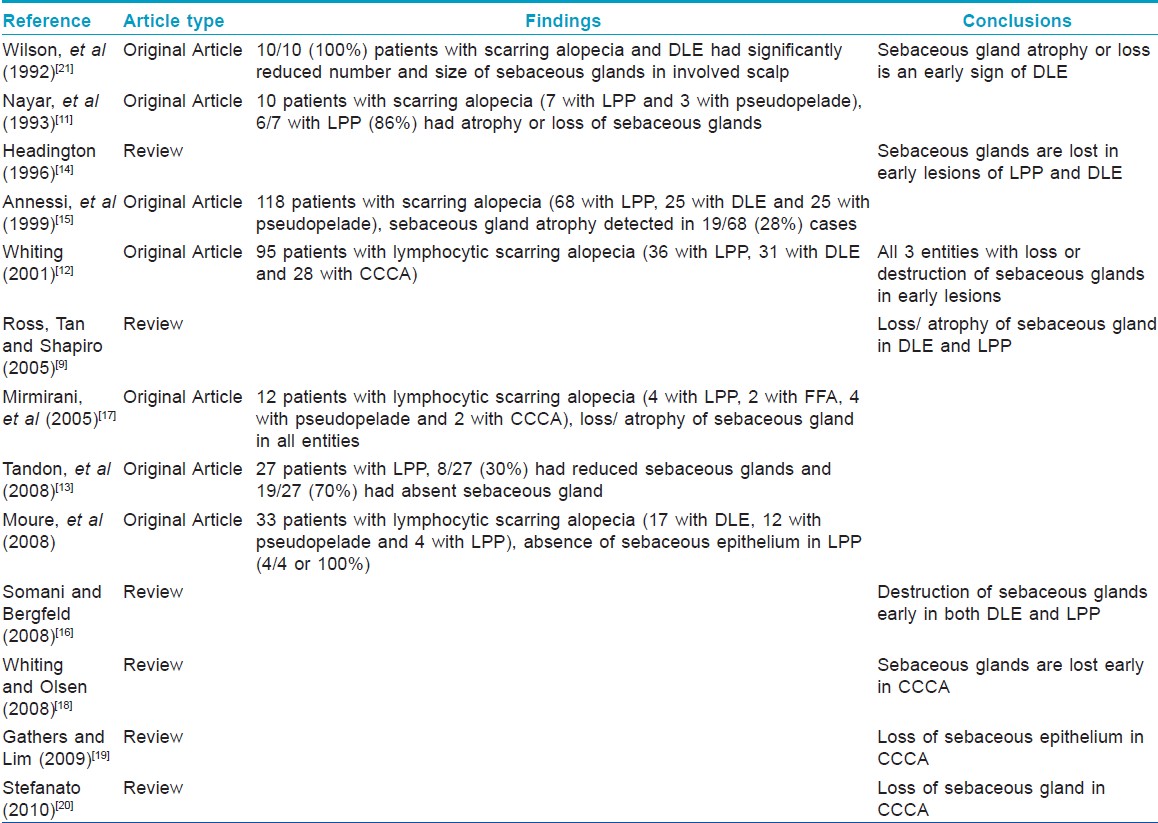

Next, we questioned whether psoriatic alopecia has specific histologic changes or if similar findings are present in other lymphocytic scarring alopecias, like central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), lichen planopilaris (LPP) or frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) and lupus. Histopathologic features seen in these entities include: Decreased or absent follicular units, a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, distention of follicular ostia (lupus), infundibular hyperkeratosis (LPP/ FFA), fibrous tracts, and naked hair shafts. [9] While the frequency of these changes varies with both the diagnosis and the stage of disease at which the biopsy is performed, the follicular changes noted in our study are not unique to psoriatic alopecia and are often present in other lymphocytic scarring.

Of interest, 87% of patients with alopecia at time of presentation had complete absence or atrophy of sebaceous glands. In a recent series, comparing 19 patients with scalp psoriasis (no clinical information on the presence, absence, or degree of alopecia mentioned) with 26 normal controls, atrophy of sebaceous glands was the only statistically significant histopathologic finding present in the psoriatic group. [10] Although this led the authors to conclude a feature "peculiar to scalp psoriasis was sebaceous gland atrophy", a retrospective review of the literature indicates that "sebaceous glands are often atrophic or absent in other lymphocytic scarring alopecias such as LPP/ FFA, [9],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15],[16],[17] CCCA, [12],[17],[18],[19],[20] and DLE [9],[12],[16],[21] [Table - 4]. In those that were original articles, the prevalence of sebaceous gland atrophy or absence in lymphocytic scarring alopecias varied from 28 to 100%, often being observed as an early event in all 3 entities.

Why does sebaceous gland atrophy/loss occur in psoriasis? One possible explanation is that psoriasis has an extremely complex cytokine milieu. The psoriatic plaque is characterized by the predominance of cytokines produced by T H1 cells. [22] Briefly, these include IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. [22] It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that the interactions of cytokines and chemokines produced in lesional epidermis could cause sebaceous glands to atrophy in an autocrine and paracrine manner akin to the role of IGFBP7 (a secreted protein produced by normal melanocytes) in BRAFV600E mutated nevi. [23] In BRAFV600E-positive nevi, constitutive activation of the BRAF-MEK- ERK pathway increases expression and secretion of IGFBP7, resulting in high levels of IGFBP7 that inhibit BRAF-MEK-ERK signaling and activate senescence. [23] Extending this analogy to psoriasis and lending credence to our hypothesis, Kristensen et al, showed that TNF-α and its receptor are expressed in basal layers of epidermis and sebaceous glands in normal skin, but are confined solely to the epidermis in psoriatic skin. [24] In addition, prior research indicates that TNF-α is present in normal sebaceous glands and murine skin, [25] is implicated in the induction of psoriatic skin lesions on the scalp including alopecia, and is reported secondary to anti-TNF-α therapy. [26],[27],[28] Of note, none of the patients in the current study were on anti-TNF-α therapy.

An alternate explanation for sebaceous gland atrophy/loss relates to the perifollicular inflammation of the upper "permanent" portion of the hair follicle present in psoriatic alopecia which is also common to all scarring alopecias. [3] Near this site (particularly where the arrector pili attaches), the bulge contains stem cells that give rise to multipotent matrix cells. [29],[30],[31] It is thought that these multipotent cells give rise to the hair shaft, as well as the sebaceous gland and adjacent epidermis. [31] Thus, damage to this region compromises the sebaceous gland. Using antibodies to stem cell markers nestin, CK15 and CD34, we previously demonstrated that the bulge region is involved in "active" stages of scarring alopecias. [32] Could alopecia be secondary response to sebaceous gland loss? Asebia mouse mutants, having markedly hypoplastic sebaceous glands, experience progressive hair loss and striking scarring alopecia. [33]

From a clinical perspective, 4 of the 7 published articles refer to psoriatic alopecia as a scarring form of alopecia, [3],[5],[6],[7] one categorizes it as a non-scarring alopecia [8] and two had features of both, [2],[4] favoring a non-cicatricial process is the presence of hair re-growth. In the largest study to date (n = 47), 7 patients experienced permanent hair loss while 34 patients had re-growth. [4] Similarly, multiple patients in our study experienced hair re-growth (4 of 7 patients with follow-up), albeit obvious limitations in the numbers of patients with follow-up (averaging 18.1 months).

While a major limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective one, given that these changes are common to varying degrees in all lymphocytic scarring alopecias, we posit that psoriatic alopecia likely represents a secondary clinical change to a primary process and is not a unique histopathologic entity. A prospective study with a control group that includes lymphocytic scarring alopecias from non-psoriasis patients is required to support our findings.

| 1. |

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Information Clearinghouse. NIAMS Fast Facts. Available from: http://www.niams nih gov. [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 24].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol 1972;87:73-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wright AL, Messenger AG. Scarring alopecia in psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70:156-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Runne U, Kroneisen-Wiersma P. Psoriatic alopecia: Acute and chronic hair loss in 47 patients with scalp psoriasis. Dermatology 1992;185:82-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Bardazzi F, Fanti PA, Orlandi C, Chieregato C, Misciali C. Psoriatic scarring alopecia: Observations in four patients. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:765-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

van de Kerkhof PC, Chang A. Scarring alopecia and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1992;126:524-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Cockayne SE, Messenger AG. Familial scarring alopecia associated with scalp psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:425-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Gul U, Soylu S, Demiriz M. Noncicatricial alopecia due to plaque-type psoriasis of the scalp. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009;75:78-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:1-37.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Werner B, Brenner FM, Boer A. Histopathologic study of scalp psoriasis: Peculiar features including sebaceous gland atrophy. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:93-100.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Nayar M, Schomberg K, Dawber RP, Millard PR. A clinicopathological study of scarring alopecia. Br J Dermatol 1993;128:533-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Whiting DA. Cicatricial alopecia: Clinico-pathological findings and treatment. Clin Dermatol 2001;19:211-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Tandon YK, Somani N, Cevasco NC, Bergfeld WF. A histologic review of 27 patients with lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:91-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Headington JT. Cicatricial alopecia. Dermatol Clin 1996;14:773- 82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Annessi G, Lombardo G, Gobello T, Puddu P. A clinicopathologic study of scarring alopecia due to lichen planus: Comparison with scarring alopecia in discoid lupus erythematosus and pseudopelade. Am J Dermatopathol 1999;21:324-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Somani N, Bergfeld WF. Cicatricial alopecia: Classification and histopathology. Dermatol Ther 2008;21:221-37.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Mirmirani P, Willey A, Headington JT, Stenn K, McCalmont TH, Price VH. Primary cicatricial alopecia: Histopathologic findings do not distinguish clinical variants. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:637-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Whiting DA, Olsen EA. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Dermatol Ther 2008;21:268-78.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: Past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:660-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Stefanato CM. Histopathology of alopecia: A clinicopathological approach to diagnosis. Histopathology 2010;56:24-38.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Wilson CL, Burge SM, Dean D, Dawber RP. Scarring alopecia in discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1992;126:307-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, Walters IB, Krueger JG. The majority of epidermal T cells in Psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effect or populations: A type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:752-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR.Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell 2008;132:363-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Kristensen M, Chu CQ, Eedy DJ, Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Breathnach SM. Localization of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and its receptors in normal and psoriatic skin: Epidermal cells express the 55-kD but not the 75-kD TNF receptor. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;94:354-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Kolde G, Schulze-Osthoff K, Meyer H, Knop J. Immunohistological and immunoelectron microscopic identification of TNF alpha in normal human and murine epidermis. Arch Dermatol Res 1992;284:154-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, Lackey J, Thomas B, Vleugels RA, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy: A novel cause of noncicatricial alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol 2011;33:161-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Nakagomi D, Harada K, Yagasaki A, Kawamura T, Shibagaki N, Shimada S. Psoriasiform eruption associated with alopecia areata during infliximab therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:923-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Shabrawi-Caelen L, La Placa M, Vincenzi C, Haidn T, Muellegger R, Tosti A. Adalimumab-induced psoriasis of the scalp with diffuse alopecia: A severe potentially irreversible cutaneous side effect of TNF-alpha blockers. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:182-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

McElwee KJ. Etiology of cicatricial alopecias: A basic science point of view. Dermatol Ther 2008;21:212-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Pozdnyakova O, Mahalingam M. Involvement of the bulge region in primary scarring alopecia. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35:922-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Lavker RM, Sun TT, Oshima H, Barrandon Y, Akiyama M, Ferraris C, et al. Hair follicle stem cells. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2003;8:28-38.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Hoang MP, Keady M, Mahalingam M. Stem cell markers (cytokeratin 15, CD34 and nestin) in primary scarring and nonscarring alopecia. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:609-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Stenn KS, Sundberg JP, Sperling LC. Hair follicle biology, the sebaceous gland, and scarring alopecias. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:973-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,871

PDF downloads

1,754