Translate this page into:

Management of autoimmune urticaria

Correspondence Address:

Arun C Inamadar

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, BLDEA's SBMP Medical College, Hospital and Research Center, Bijapur - 586 103, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Inamadar AC, Palit A. Management of autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:89-91 |

|

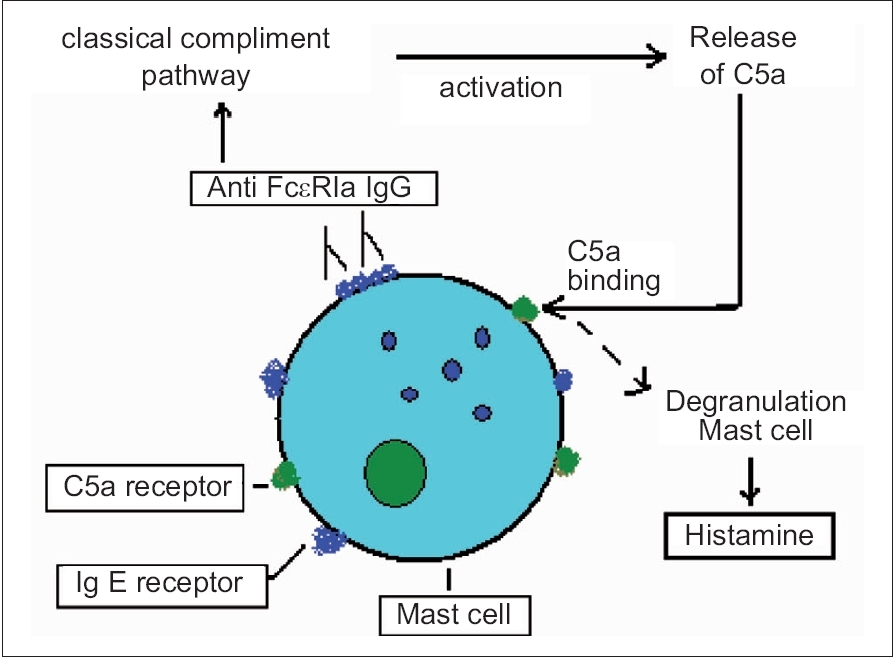

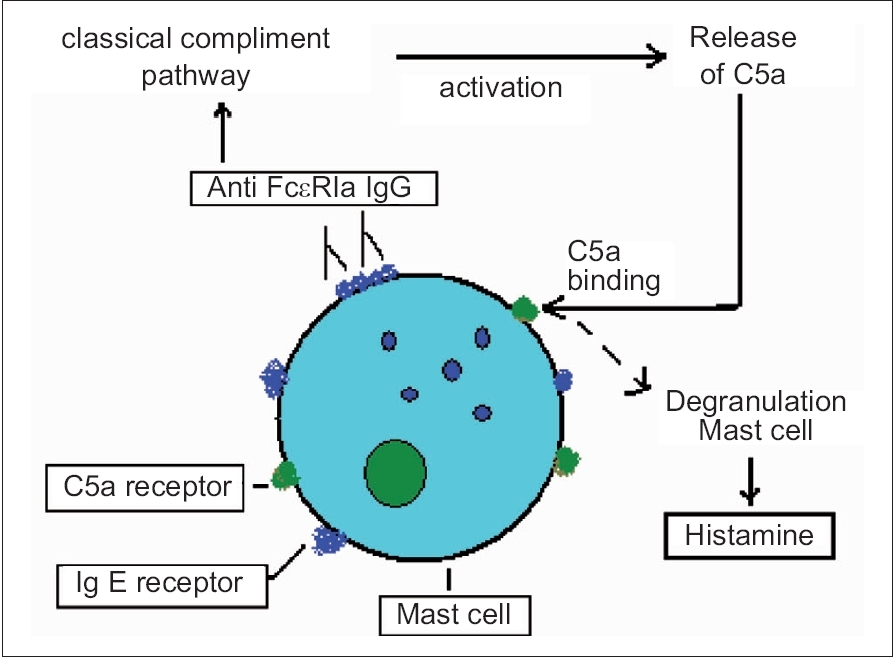

| Figure 1: Diagrammatic illustration of mast cell activation in autoimmune urticaria |

|

| Figure 1: Diagrammatic illustration of mast cell activation in autoimmune urticaria |

Chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) is one of the most vexing management problems that dermatologists face. However, recognition of autoimmune urticaria (AIU) as a distinct subgroup of CIU during the last decade has facilitated better understanding of unremitting CIU.

About 40-50% of the patients with CIU demonstrate an immediate wheal and flare response to intra-dermally injected autologous serum. [1] This led to the concept of AIU, which is now a widely accepted entity. These patients demonstrate circulating histamine-releasing IgG autoantibodies against the high affinity IgE receptor F cεR Iα (35-40%) on dermal mast cells and basophils or less commonly to IgE itself (5-10%). [2] Basophil and mast cell degranulation leads to the release of histamine, which is demonstrable by the autologous serum skin test (ASST). These autoantibodies may also be present in healthy individuals (natural autoantibodies) but are capable of triggering histamine release only if the receptors are IgE-free. [3]

Positive results in ASST give an approximate idea of basophil and mast cell histamine-releasing propensity of a patient with CIU. In an earlier Indian study, ASST positivity was found to be 26.67% in chronic urticaria. [4] This issue carries two larger studies by Mamatha et al. [5] and Bajaj et al. [6] with 34 and 49.5% ASST positivity respectively among their patients with chronic urticaria.

Clinically, these patients present with typical urticaria and angioedema, not differing much from usual chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) except in terms of severity. [1],[7] In the Indian study by Mamatha et al. [5] the frequency and severity of the episodes of urticaria, duration of individual lesions and systemic symptoms were more in patients giving positive ASST results. However, there was no significant difference among ASST-positive and ASST-negative groups of patients regarding demographic profiles, distribution of skin lesions and presence of angioedema; occurrence of dermographism was higher among ASST-negative patients. [5] A pointer to the clinical possibility of AIU is the refractoriness of the urticaria to optimum, off-label dosage of conventional antihistamine therapy administered for sufficient duration. [1]

These patients may have clinical hypo- or hyperthyroidism and anti-thyroid antibodies are present in 27% of the cases. [8] Bakos et al. [9] have discussed the possibility of H. pylori acting as a trigger factor in some patients with AIU and the co-existence of autoimmune thyroiditis may be determined by the presence of Cag A+ strains of H. pylori . Personal or family history of other autoimmune diseases such as pernicious anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, vitiligo and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus may be present. [10]

The circulating IgG isotypes responsible in the pathogenesis of AIU are IgG 3 (primary), IgG 1 (frequent) and IgG 4 (occasional). [2] The binding of the autoantibodies to F cεR Iα may be competitive or noncompetitive. [8] This binding leads to the activation of the classical complement pathway releasing C5a. [8] C5a binds to the respective receptors on the mast cell surface augmenting histamine secretion by degranulation [Figure - 1]. [8]

The only in vivo screening test for AIU is ASST with a sensitivity and specificity of 70 and 80% respectively in the detection of histamine release by basophils and cutaneous mast cells. [1] Peripheral blood basophil count is reduced or absent in patients with AIU. [11] The confirmatory diagnostic tests include basophil CD63 expression assay and basophil histamine release assay. [10],[12] These tests are not available in India and access to them is limited even in developed countries.

Histopathological features of AIU remain almost indistinguishable from CIU except for a more intense granulocyte infiltrate in the former. [8],[10] Thyroid function tests and screening for thyroid autoantibodies are recommended only in the presence of clinical features of thyroid dysfunction. [13] In the series of patients studied by Mamatha et al. [5] three ASST-positive patients showed abnormal thyroid function tests.

Patients with AIU are poor responders to conventional antihistamine therapy. When the wheals are uncontrolled in spite of optimum dosage of non-sedating and sedating antihistamines, adjunctive medications like H2 receptor antagonists and leukotriene antagonists should be attempted. [8] However, monotherapy with oral leukotriene receptor antagonist (montelukast) was found to be ineffective in a group of Indian patients with CIU demonstrating positive ASST. [14] Short-term, alternate day regimen of systemic steroids may be used to tackle severe, persistent episodes but steroids do not affect mast cell degranulation or complement activation.

When the disease is disabling, immunosuppressive therapy is warranted. Although these therapies should bring dramatic effect to this disorder of autoimmune pathogenesis, only selected patients are found to be responsive. The drugs which have been tried for this purpose include cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. [10]

Cyclosporine is a steroid-sparing drug in the management of AIU. It is used where steroids are contraindicated or in patients who have developed significant side effects due to prolonged use of systemic steroids. [8] Cyclosporine has been found to be effective, used in the dosage of 3-5 mg/kg/day for a minimum period of 1 month. [13] An excellent response (>75%) has been observed following 12 weeks of cyclosporine therapy, of which 1/3 rd patients achieved complete remission, 1/3 rd had mild relapse and the rest experienced a relapse to pretreatment levels. [15] Continuation of antihistamine therapy is recommended along with cyclosporine. [13] The mechanism of action of cyclosporine includes inhibition of basophil and mast cell degranulation by interfering with intracellular signaling in cells following cross-linking of the IgE receptor. [8],[15] Close monitoring of patients on cyclosporine therapy is needed.

Weekly methotrexate therapy (2.5 mg every 12 h for 2 days/week, followed by the same dosage 3 days/week for 6 weeks) has been found to be effective in decreasing pruritus and wheals and improving sleep and daily activities. [16] Although this has little effect on angioedema, it has been proposed as a cost-effective alternative to cyclosporine even in Indian set-up. [17]

Intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg for 5 days) was effective in relieving symptoms in patients with chronic AIU and achieving ASST negativity as well as long-term (>3 years) remission. [18] Complete, permanent remission was reported in patients who attained ASST negativity within 6 months of therapy. [18] High-dose, intravenous immunoglobulin monotherapy (2 g/kg over 24 h) has also been used successfully. This one-time therapy had brought complete remission for 7 months; relapse occurred thereafter and repetition of the same therapy resulted in only moderate response. [19] Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, presence of anti-idiotypic antibodies capable of suppressing IgE autoantibodies, in the intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) preparation has been suggested. [20]

Plasmapheresis was found to be beneficial in a small series of patients with AIU by eliminating the functional autoantibodies from system. [21]

Futuristic therapeutic options include selective immunotherapy using humanized, structure-based peptides by epitope mapping of the α-chain of high-affinity IgE receptors. [8] DNA-plasmid vaccination to induce tolerance to the α-chain and use of specific antibodies like humanized, monoclonal anti-IgE can be another specific intervention. [10]

Bajaj et al. [6] have used autologous serum therapy (AST) for two groups of patients with CIU (ASST-positive and ASST-negative) and found it to be an effective therapeutic modality to reduce disease severity as well as antihistamine requirement. This also prevented relapse of symptoms for durations as long as 2 years.

The interesting finding in the study by Bajaj et al. [6] is that the ASST-negative group responded almost equally well to AST as the ASST-positive group. This has raised a question regarding the validity of ASST in detecting AIU. In this context, the possibility of the existence of a subset of patients with AIU who are ASST-negative may also be considered. It is probable that these patients possess a different isotype of anti-α IgG than ASST-positive patients (IgG 1 , IgG 3, IgG 4 ), which has a lesser ability to release histamine by basophil activation. The IgG 4 fraction detected in some patients with AIU is not complement-fixing. [2] The IgG 2 autoantibody has been demonstrated in patients with CIU with negative results in the histamine release assay, irrespective of IgG 2 anti-α antibody immunoblot positivity. [8] Moreover, the anti-F cεR Iα autoantibodies found in some other disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus(SLE), dermatomyositis and bullous pemphigoid (IgG 2 , IgG 4 ) are incapable of histamine release from basophils and mast cells. [10],[13] Hence, a possibility exists that some patients with AIU have predominant IgG 4 anti-α or IgG 2 anti-α antibodies and thus, they may display ASST negativity. This can be proved or nullified by IgG subclass analytic assays in such patients in future studies.

This may partially explain the therapeutic response of some ASST-negative patients to AST. This therapeutic modality can be tried in difficult-to-manage patients with CIU even if they are ASST-negative.

Autoimmune urticaria remains a therapeutic dilemma. Immunosuppressive drugs are useful in some cases. However their use is limited by factors like need for prolonged therapy, related side effects, presence of co-morbid disorders, need for elaborate laboratory testing, regular patient monitoring, and high cost of therapy. AST may be a ray of hope in the management of AIU.

| 1. |

Greaves M. Chronic idiopathic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;3:363-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Soundararajan S, Kikuchi Y, Joseph K, Kaplan AP. Functional assessment of pathogenic IgG subclasses in chronic autoimmune urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:815-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Pachlopnik JM, Horn MP, Fux M, Dahinden M, Mandallaz M, Schneeberger D, et al . Natural anti-Fcepsilon RIalpha autoantibodies may interfere with diagnostic tests for autoimmune urticaria. J Autoimmun 2004;22:43-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Godse KV. Autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004; 70:283-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Mamatha G, Balachandran C, Smitha P. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Comparison of clinical features with positive autologous serum sensitivity test. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:105-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Bajaj AK, Saraswat A, Upadhyay A, Damisetty R, Dhar S. Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: Old wine in a new bottle. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:109-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Caproni M, Volpi W, Giomi B, Cardinali C, Antiga E, Melani L, et al . Chronic idiopathic and chronic autoimmune urticaria: Clinical and immunopathological features of 68 subjects. Acta Derm Venereol 2004;84:288-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: Pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;114:465-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Bakos N, Hillander M. Comparison of chronic autoimmune urticaria with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:613-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Grattan CE, Sabroe RA, Greaves MW. Chronic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:645-57.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Grattan CE, Walpole D, Francis DM, Niimi N, Dootson G, Edler S, et al . Flow cytometric analysis of basophil numbers in chronic urticaria: Basopenia is related to serum histamine releasing activity. Clin Exp Allergy 1997;27:1417-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Gyμmesi E, Sipka S, Dank� K, Kiss E, Hνdvιgi B, Gαl M, et al . Basophil CD63 expression assay on highly sensitized atopic donor leucocytes: A useful method in chronic autoimmune urticaria. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:388-96.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Kozel MM, Sabroe RA. Chronic urticaria: Aetiology, management and current and future management options. Drugs 2004;64:2515-36.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Godse KV. Oral montelukast monotherapy is ineffective in chronic idiopathic urticaria: A comparison with oral cetirizine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006; 72:312-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;105:664-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Montero Mora P, Gonzαlez Pιrez Mdel C, Almeida Arvizu V, Matta Campos JJ. Autoimmune urticaria: Treatment with methotrexate. Rev Alerg Mex 2004;51:167-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Godse KV. Methotrexate in autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004; 70:377.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

O'Donnell BF, Barr RM, Black AK, Francis DM, Karmani F, Niimi N, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:101-6.

et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:101-6.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Klote MM, Nelson MR, Engler RJ. Autoimmune urticaria response to high dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005;94:307-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

R�tter A, Luger TA. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: An approach to treat severe immune-mediated and autoimmune diseases of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:1010-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Grattan CE, Francis DM, Slater NG, Barlow RJ, Greaves MW. Plasmapheresis for severe, unremitting, chronic urticaria. Lancet 1992;339:1078-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

6,540

PDF downloads

3,283