Translate this page into:

Recurrent, scarring penile ulcers

2 Division of DVL,Rajah Muthiah Medical College, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, India

3 Department of Patholgy,Rajah Muthiah Medical College, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, India

4 Department of Community Medicine, Rajah Muthiah Medical College, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, India

Correspondence Address:

L Padmavathy

B3, RSA Complex, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar-608002, Tamil Nadu

India

| How to cite this article: Padmavathy L, Chockalingam K, Rao LL, Ethirajan N. Recurrent, scarring penile ulcers. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:86 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A 35-year-old male complained of recurrent crops of asymptomatic papules on his glans penis for the past few weeks. They ruptured, ulcerated and healed with tiny depressed scars.

On examination, he had multiple tiny ulcers, papules and pitted scars arranged in a more or less linear fashion on the glans penis near the coronal sulcus [Figure - 1]. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. He denied any pre-marital or extra-marital sexual contact.

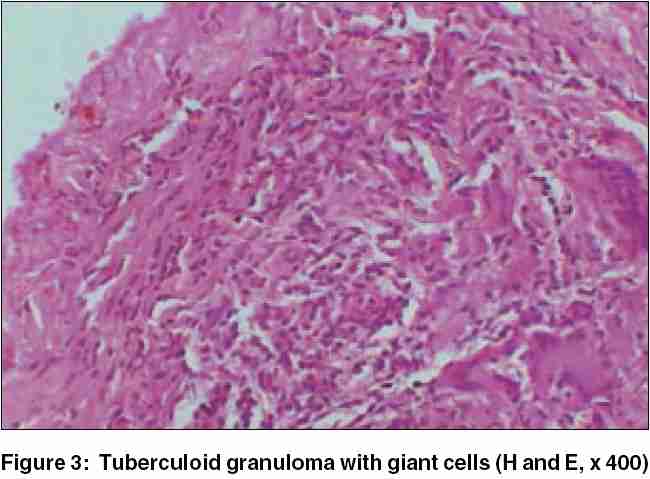

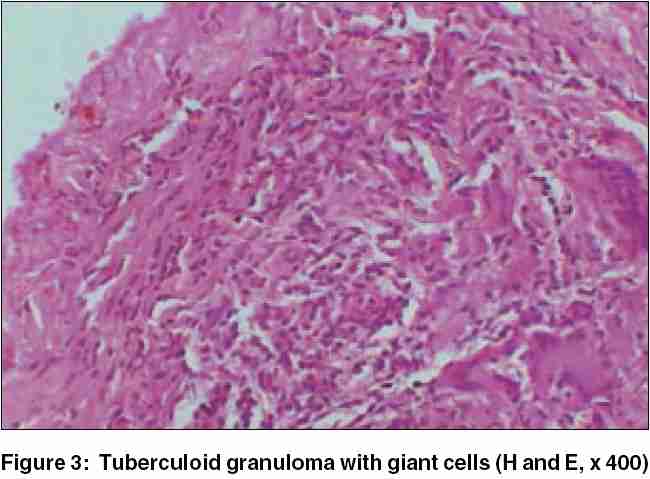

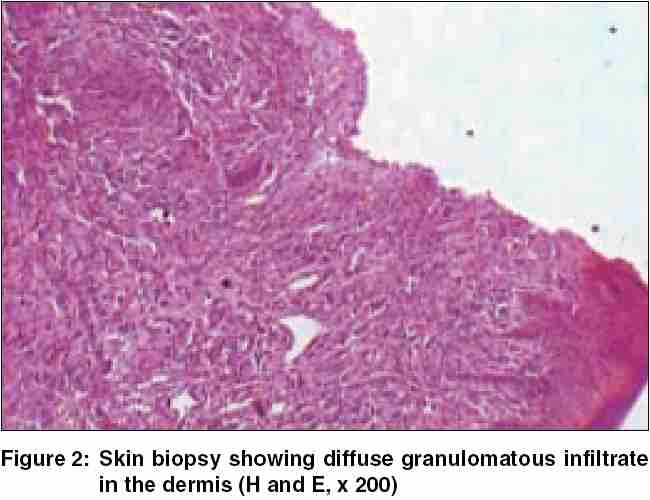

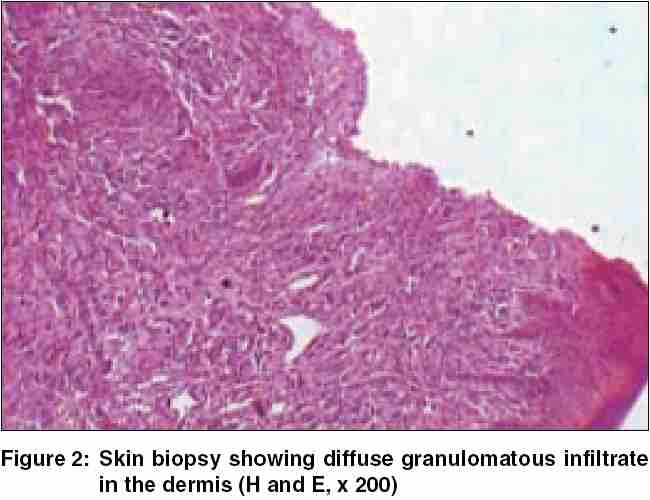

All relevant biochemical and hematological parameters and X-ray chest were within normal limits. Smears from the ulcers and serum VDRL and HIV (ELISA) tests were negative. A biopsy from one of the lesions revealed tuberculoid granulomatous dermatitis [Figure - 2][Figure - 3].

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Papulonecrotic tuberculide

Histopathology: Skin biopsy shows ulceration and granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells.

The term tuberculide was first used by Darier in 1896 to denote recurrent, papular and nodular skin eruptions usually disseminated and symmetric, showing a tendency to spontaneous involution.[1] Pautrier in 1936 first described PNT and established its tuberculous etiology.[3] Though M. tuberculosis is the most common etiological agent, a case of PNT as a reaction to M. kansasii was recently reported.[3] PNT is most commonly seen in adults, with a female preponderance (M: F = 1:3).[4] It is characterized by an eruption of necrotizing papules occurring in symmetrical crops, particularly affecting the elbows, knees, buttocks and face and responding to antituberculous treatment. Associated clinical features described are tuberculous arthritis with gangrene, lymphadenopathy, phlyctenular conjunctivitis and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.[5] There are reports of the simultaneous occurrence of two tuberculides, erythem induratum and papulonecrotic tuberculides.[6],[7] Lupus vulgaris is also reported to develop from PNT.[7]

Biopsy, a general physical examination and tuberculin testing are necessary to establish the diagnosis. The histopathological characteristics depend on the age of lesions, and range from subacute lymphocytic vasculitis to granulomatous vasculitis with focal infarction and coagulative necrosis, which is characteristically "flask shaped" when viewed under low power.[7] Tuberculin sensitivity is intense.

It is suggested that PNT begins as an Arthus reaction, followed by a delayed hypersensitivity response, which

will prevent the local proliferation of M. tuberculosis .[7] The patients′ active immune system destroys all evidence of the bacilli in the skin, making stains and cultures negative.[8] However PCR examination may reveal evidence of M. tuberculosis .[9] In a large series of 91 cases of PNT, only 38% had a focus of tuberculosis.

Though strongly Mantoux positive, our patient did not have any clinical or radiological evidence of a tuberculous focus. In 1977, Kumar and Kaur described a case of PNT on the penis, which is probably the first such report from India.[1] There are also reports of involvement of the glans penis from other countries.[4],[8]

Our patient was treated with standard anti-tuberculous treatment and there was no recurrence.

| 1. |

Kumar B, Kaur S. Papulonecrotic tuberculide. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1977;43:212-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Callahan EF, Licata AL, Madison JF. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasi infection associated with a papulonecrotic tuberculide reaction. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:497-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wilson-Jones E, Winkelman RK. Papulonecrotic tuberculide: a neglected disease in the western countries. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;14:815-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ramdial PK, Mosam A, Malette R, Aboobaker J. Papulonecrotic tuberculide in a 2-year-old girl: with emphasis on extent of disease and the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;15:450-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Sloan JB, Medenica M. Papulonecrotic tuberculide in a 9-yearold American girl: case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol 1990;7:191-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Degitz K, Steidl M, Thomas P, Plewig G, Volkenandt M. Aetiology of tuberculides. Lancet 1993;341:239-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Roblin D, Kelly R, Wansbrough-Jones M, Harwood C. Papulonecrotic tuberculide and erythema induratum as presenting manifestations of tuberculosis. J Infection 1994;28:193-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Papali C, Gangadharan C, Ramachandran Nair P, Asokan PU. Tuberculides - A concept. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1973;39:276-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Kumar B, Rai R, Kaur I, Sahoo B, Muralidhar S, Radotra BD. Childhood cutaneous tuberculosis - a study over 25 years from northern India. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:26-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,392

PDF downloads

1,183