Translate this page into:

An elderly man with a violaceous nodule and anemia

2 Department of Pathology, BLDEA's SBMP Medical College, Hospital & Research Centre, Bijapur, Karnataka, India

Correspondence Address:

Arun C Inamadar

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, BLDEA's SBMP Medical College, Hospital & Research Centre, Bijapur-586103, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Palit A, Inamadar AC, Athanikar S B, Sampagavi V V, Deshmukh N S, Yelikar B R. An elderly man with a violaceous nodule and anemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:376-378 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A 60-year-old agricultural worker, admitted to the surgical ward for bleeding piles of long duration, was referred for evaluation of his skin lesions. He had developed a painful nodule on his left thigh for the past 4 weeks, which had been enlarging rapidly since its onset.

On general physical examination, the patient was pale and emaciated. There were multiple ecchymotic patches over both forearms and legs. A violaceous, shiny nodular lesion of about 4 cm x 4 cm was observed on the extensor aspect of his left thigh [Figure - 1]. The lesion was firm, non-compressible, movable over the underlying structures and slightly tender. Systemic examination revealed hepatosplenomegaly.

A complete hemogram revealed Hb, 7 gm%; TLC, 11,300/cmm; differential count: neutrophils, 42%; lymphocytes, 52%; eosinophils, 4%; and monocytes, 2%; platelet count 60,000/cmm; and ESR, 120 mm at the end of the 1st hour. The peripheral blood smear showed predominantly normocytic, normochromic, few hypochromic, microcytic and nucleated RBCs. A few large cells with atypical morphology were observed.

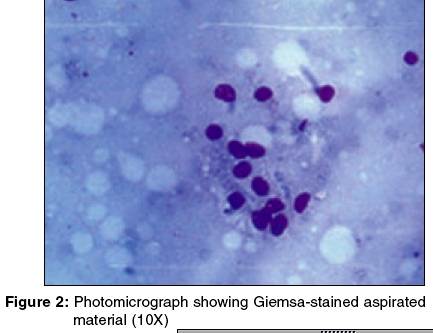

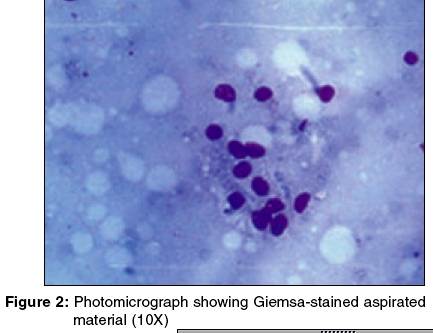

The Giemsa-stained photomicrograph of the aspirated material from the nodule has been presented in [Figure - 2].

What is the diagnosis?

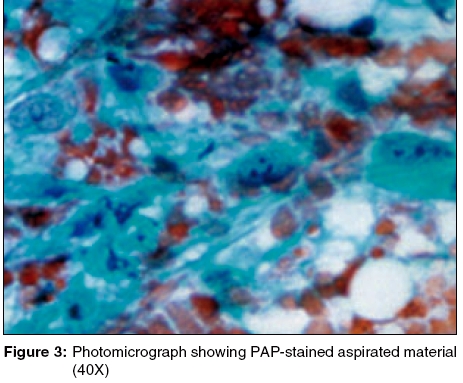

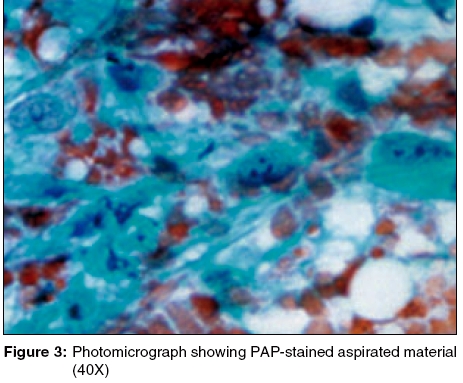

Diagnosis: 0 Granulocytic sarcoma associated with acute myeloid leukemia The Giemsa-stained FNAC smear showed clusters of blast cells [Figure - 2]. The PAP-stained smear showed large myeloid precursor cells with coarse granules, suggestive of myeloblasts [Figure - 3]. A differential count revealed myeloblasts, 60%; neutrophils, 26%; lymphocytes, 10%; and monocytes, 4%.

The patient was referred to the Medicine Department for further work-up and bone marrow aspiration studies. He refused further invasive investigations and left the hospital against medical advice.

Discussion

Granulocytic sarcoma (GS) is a rare tumor resulting from extramedullary invasion of granulocyte precursor cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[1] It is variably known as myeloid sarcoma, myeloblastoma or chloroma. The tumors are usually localized to the bone, periosteum, soft tissue, lymph node or skin.[1] The commonest extracutaneous sites are skull bones, orbit and paranasal sinuses, but involvement of intracranial structures, viscera, serous membranes, breast and salivary glands has been reported.[1] When the skin is involved, it constitutes a specific form of leukemia cutis. The lesion occurs as a solitary, rapidly enlarging nodule, occasionally with a greenish hue.

The overall incidence of GS varies from 2% to 14%.[1] It is common in children and younger patients with AML. GS may occur in three clinical situations:[2]

· In patients with AML,

· Rarely, in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome with leukemic transformation or chronic myeloid leukemia with impending blast crisis, or

· In patients without hematological or bone marrow evidence of acute myeloid leukemia (aleukemic leukemia cutis).

The occurrence of GS in patients with AML is a poor prognostic factor, indicating a life expectancy of one year in 90% of the cases.[3] In patients of myelodysplastic syndrome with GS, there is a definite progression to AML. The majority of patients with aleukemic leukemia and GS develop overt AML within a mean period of 10 months.[3]

The pathogenesis of GS is unknown. It has been speculated that trauma induced extravasation of myeloid precursor cells in the skin leads to their localized replication.[3] Recently, the role of the neural cell adhesion molecule CD56 has been highlighted. Co-expression of CD56 and CD4 on the tumor cells and co-existent 8:21 chromosome translocation have been implicated as possible risk factors for the development of GS in patients with AML.[2]

The earlier name chloroma was derived from the greenish color of some of the tumors which results from the increased level of myeloperoxidase enzymes in the immature cells.[4] The color can be enhanced by rubbing the tumor with alcohol swabs.[3] It also fluoresces red under ultraviolet light due to the presence of protoporphyrin.[5] The diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy, dried imprint smears and cytological preparations.

Histopathological features include a dense population of myeloblasts, myelocytes and some mature cells infiltrating the collagen fibers and deeper tissues.[1] Focal necrosis may be present. The nature of the granules (eosinophilic/neutrophilic) may indicate the cells′ myeloid lineage. Peripheral blood and bone marrow examinations are essential for management. Neutropenia is common in patients with GS.[1]

The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous B-cell lymphoma,[6] which may clinically present as a single or multiple violaceous nodules involving the head, neck or trunk. Histopathologically, there is a bottom-heavy infiltrate of lymphocytes sparing the epidermis. In some cases, immunohistochemistry, flow-cytometry or cytochemical stains may be required to exclude lymphoma.[6] Pseudochloroma is a rare condition characterised by the collection of normal hemopoietic tissue in unusual locations.[5] It can be differentiated from GS by the constituent mature cells.

No established treatment is available for individual lesions of GS. The lesions are radiosensitive.[1] Radiotherapy and electron-beam therapy are palliative and causes rapid shrinkage of the lesions.[3] In view of the frequent subsequent relapse, systemic chemotherapy, as recommended for the underlying hematological condition, is the preferred mode of treatment.

| 1. |

Greer JP, Baer MR, Kinney MC. Acute myeloid leukemia in adults. In: Greer JP, Foerster J, Lukens JN, Rodgers GM, Paraskevas F, Glader B, editors. Wintrobe's Clinical hematology. 11th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2004. p. 2097-142.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Murakami Y, Nagae S, Matsuishi E, Irie K, Furue M. A case of CD 56+ cutaneous aleukemic granulocytic sarcoma with myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:587-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Harris DW, Ostlere LS, Rustin MH. Cutaneous granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) presenting as the first sign of relapse following autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Br J Dermatol 1992;127:182-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:161-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Ashley DJ. Myeloid leukemia and allied disorders. In: Ashley DJB, editor. Evans' Histopathological appearances of tumors, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. p. 191-204.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Zic JA, Kiripolsky MG, Hamilton KS, Greer JP. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, mycosis fungoides and Sιzary syndrome. In: Greer JP, Foerster J, Lukens JN, Rodgers GM, Paraskevas F, Glader B, editors. Wintrobe's Clinical hematology, 11th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2004. p. 2485-520.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,240

PDF downloads

4,699