Translate this page into:

Psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus is similar to vitiligo, but greater than melasma: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary-care center in north India

Corresponding author: Dr. Vinod Kumar Sharma, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi - 110 029, India. aiimsvks@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gupta V, Yadav D, Satapathy S, Upadhyay A, Mahajan S, Ramam M, et al. Psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus is similar to vitiligo, but greater than melasma: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary-care center in north India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:341-7.

Abstract

Background:

Lichen planus pigmentosus can have a negative impact on the quality of life; however, this has not been studied in detail.

Objectives:

To study the quality of life in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and compare it with patients with vitiligo and melasma.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in a tertiary-care center in north India from January 2018 to May 2019. Patients ≥ 18 years of age with lichen planus pigmentosus (n = 125), vitiligo (n = 113) and melasma (n = 121) completed the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire and answered a global question on the effect of disease on their lives. In addition, patients with vitiligo completed the Vitiligo Impact Scale (VIS)-22 questionnaire, while those with lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma filled a modified version of VIS-22.

Results:

The mean DLQI scores in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma were 10.9 ± 5.95, 9.73 ± 6.51 and 8.39 ± 5.92, respectively, the difference being statistically significant only between lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma (P < 0.001). The corresponding mean modified VIS-22/VIS-22 scores were 26.82 ± 11.89, 25.82 ± 14.03 and 18.87 ± 11.84, respectively. This difference was statistically significant between lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma, and between vitiligo and melasma (P < 0.001 for both). As compared to vitiligo, patients with lichen planus pigmentosus had a significantly greater impact on “symptoms and feelings” domain (P < 0.001) on DLQI, and on “social interactions” (P = 0.02) and “depression” (P = 0.04) domains on VIS-22. As compared to melasma, patients with lichen planus pigmentosus had significantly higher scores for “symptoms and feelings,” “daily activities,” “leisure” and “work and school” domains of DLQI, and all domains of VIS-22. Female gender was more associated with impairment in quality of life in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, while lower education, marriage, younger age and increasing disease duration showed a directional trend.

Limitations:

Use of DLQI and modified version of VIS-22 scales in the absence of a pigmentary disease-specific quality-of-life instrument.

Conclusion:

Patients with lichen planus pigmentosus have a significantly impaired quality of life. The psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus is quantitatively similar to that of vitiligo, but significantly greater than melasma.

Keywords

Lichen planus pigmentosus

melasma

pigmentary dermatoses

quality of life

vitiligo

Introduction

Pigmentary disorders are known to have a negative psychosocial impact on patients’ lives, primarily because of cosmetic disfigurement.1,2 However, the health-related quality of life has received attention in only a select few pigmentary dermatoses. Lichen planus pigmentosus is characterized by dark brown to slate gray macules predominantly on photoexposed and flexural sites. It typically affects middle-aged individuals, usually women with darker skin types.3 Though the exact etiopathogenesis is not understood, there may be several triggers including contact allergens, food allergens, drugs, viral infections and hypothyroidism. About a third of patients with lichen planus pigmentosus can have a positive patch test to cosmetics.4,5 There has been a renewed interest in lichen planus pigmentosus and related entities, and attempts have been made to address the controversy regarding their nomenclature in the last few years.6-9 Owing to a large degree of clinicopathological overlap with conditions such as ashy dermatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis, hypernyms such as “acquired macular dermal hyperpigmentation” and “macular pigmentation of uncertain etiology” have been proposed.6,7 Despite the increasing recognition of a potential negative impact of lichen planus pigmentosus on the quality of life of patients, no study has been undertaken to formally evaluate it so far. We conducted this study to evaluate the quality of life in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and compare it with two other common pigmentary disorders, vitiligo and melasma.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study conducted in the outpatient department of dermatology and venereology of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India after institute ethics clearance (IEC-611/03.11.2017), from January 2018 to May 2019.

Study population

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma were included in the study. To differentiate lichen planus pigmentosus from other similar entities (ashy dermatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis), its diagnosis was made by two experienced dermatologists based on the clinical features of slate-gray-to-brown macules on the face with or without involvement of other sites (trunk, flexures) in the absence of preceding erythema or inflammation. The pigmented macules lacked an erythematous halo. Possibility of a contact allergen causing the pigmentation was excluded by a lack of temporal correlation on detailed history and the pattern of pigmentation on clinical examination. 5,10 Patients ≥18 years of age were included in the study after giving informed consent. Patients with other skin diseases concurrently and those with psychiatric comorbidities were excluded.

Quality-of-life measures

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), vitiligo impact scale (VIS)-22 and a global question were used for measuring the quality of life in the study patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma. The DLQI is a valid and reliable dermatology-specific quality-of-life instrument containing ten items related to different domains of life. Each item is scored on a scale of 0–3 (0-not at all, 1-a little, 2-a lot, 3-very much), and the total scores range from 0–30.11 We anticipated that DLQI, being a general dermatology instrument, might not be sensitive enough to the unique quality-of-life issues in patients with pigmentary dermatoses. In the absence of an instrument specific for pigmentary dermatoses, we chose VIS-22, an instrument developed and validated in Indian patients with vitiligo. It has 22 items related to different domains of life: attitude (items 1, 4, 17, 19), anxiety (2, 11), social interactions (3, 12, 13), self-confidence (5, 18), depression (6, 9, 10, 14), treatment (7, 15, 16), family (8), marriage (20), occupation (21) and school or college (22). Each item is scored from 0–3 (0-not at all, 1-a little, 2-a lot, 3-very much), and the total scores range from 0–66 with higher scores indicating a higher effect on life. Its reliability and responsiveness have been demonstrated in vitiligo, and clinical meaning has been assigned to its scores.12,13 A modified version of VIS-22 was used as a quality-of-life measure for lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma, after testing its validity in patients with these diseases. The modified version of VIS-22 differed from VIS-22 in only one question (item 20) where the phrase “white patches” was replaced with “patches”. In addition to DLQI and modified version of VIS-22/VIS-22, a global question (“How much does your skin disease affect your life?”) concerning the effect of the disease on the patients’ lives was also asked. The response was on a five-point Likert scale: 0, no effect; 1, mild effect; 2, moderate effect; 3, large effect and 4, very large effect.

Pretesting of modified VIS-22 in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and melisma

Study participants with lichen planus pigmentosus (n = 35) and melasma (n = 20), recruited through purposive sampling, were asked to answer the modified version of VIS-22. Participants were then interviewed regarding the clarity, understandability and relevance of individual items of modified VIS-22, and also whether any aspect of their disease is not covered in the modified VIS-22.

Validity of modified VIS-22 in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and melisma

DLQI, modified VIS-22 and global question were self-administered by a separate cohort of patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma. Concurrent and convergent validities were assessed by correlating the scores of modified VIS-22 with that of the global question and DLQI, respectively. Known-group’s validity was calculated by comparing the scores of modified VIS-22 between patients grouped on the basis of gender, disease duration, disease progression, number of sites and body surface area affected, education, marital and employment status. These analyses were done separately for patients with lichen planus pigmentosus as well as melasma.

Statistical analysis

Quality of life was estimated by global question scores and the overall scores of modified VIS-22 / VIS-22 and DLQI. Scores for individual domains of modified VIS-22 / VIS-22 and DLQI were also calculated. Continuous variables are reported as mean (standard deviation, range), and categorical variables as frequency (%). Continuous variables were compared using student’s t-test or Wilcoxon ranksum test, and categorical variables by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as applicable. Correlation between two quality-of-life measures was tested using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Clinicodemographic variables associated with impairment in quality of life were identified by univariate and stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis (with a probability to enter = 0.051 and probability to remove = 0.1) using dichotomized DLQI scores (0–10, no-moderate effect vs. 11–30, large or very large effect) and global question scores (0–2, no-moderate effect vs. 3–4, large or very large effect) as dependent variables, as well as stepwise multiple linear regression analysis using continuous DLQI and modified VIS-22 scores. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, U. S. A.).

Results

There were 125 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, 113 patients with vitiligo and 121 with melasma. The clinicodemographic profile of patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma is summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | LPP (n=125), n (%) | Vitiligo (n=113), n (%) | Melasma (n=121), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 32 (25.6) | 51 (45.1) | 34 (28.1) |

| Women | 93 (74.4) | 62 (54.8) | 87 (71.9) |

| Age (years), mean±SD (range) | 34.6±11.3 (18-63) | 29.9±10.9 (18-66) | 34.4±7.7 (20-58) |

| Disease duration(years), mean±SD(range) | 4.0±5.1 (0.02-43) | 11.2±7.1 (0.5-35) | 5.0±4.4 (0.2-20) |

| <5 | 88 (70.4) | 22 (19.47) | 71 (58.68) |

| 5-10 | 31 (24.8) | 41 (36.28) | 37 (30.58) |

| >10 | 6 (4.8) | 50 (44.25) | 13 (10.74) |

| Progressive disease | 62 (49.6) | 73 (64.6) | 87 (71.9) |

| Sites affected | |||

| Head and neck | 123 (98.4) | 71 (62.8) | 121 (100) |

| Trunk | 68 (54.4) | 64 (56.6) | 0 |

| Upper limbs | 38 (30.4) | 79 (69.9) | 0 |

| Lower limbs | 23 (18.4) | 94 (83.2) | 0 |

| Number of anatomical sites affected | |||

| 1 | 51 (40.8) | 17 (15.04) | 121 (100) |

| 2 | 35 (28) | 26 (23) | 0 |

| 3 or more | 39 (31.2) | 70 (61.9) | 0 |

| Body surface area affected | n=116 | n=113 | n=121 |

| <5% | 78 (62.4) | 79 (69.9) | 121 (100) |

| 5%-10% | 27 (21.6) | 21 (18.6) | 0 |

| >10% | 11 (8.8) | 13 (11.5) | 0 |

| Married | 80/125 (64.5) | 52/113 (46) | 89/120 (74.2) |

| Employed | 50/120 (41.6) | 49/111 (44.1) | 54/120 (45) |

| Education >12 class | 70/105 (66.7) | 64/107 (59.8) | 59/109 (54.1) |

| GQ | |||

| 0 (no effect) | 8 (6.4) | 15 (12.4) | 8 (7.08) |

| 1 (mild effect) | 23 (18.4) | 32 (26.45) | 27 (23.89) |

| 2 (moderate effect) | 27 (21.6) | 26 (21.49) | 34 (30.09) |

| 3 (large effect) | 28 (22.4) | 33 (27.27) | 27 (23.89) |

| 4 (very large effect) | 39 (31.2) | 15 (12.4) | 17 (15.04) |

GQ: global question, SD: standard deviation, LPP: lichen planus pigmentosus

Pretesting and validity of modified VIS-22 in lichen planus pigmentosus and melisma

The modified VIS-22 was first administered to 35 (10 men, 25 women; mean age 35.5 ± 11.7 years) patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and 20 (6 men, 14 women; mean age 36.6 ± 7.8 years) patients with melasma. Three (8.6%) patients with lichen planus pigmentosus reported at least one item as not relevant to their disease (items 4, 7, 9, 13, 14, 16 and 17, of which items 9 and 14 were reported by two patients each). Six (30%) patients with melasma reported at least one item as not relevant to their disease (items 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, 14 and 20 of which item 4 was reported by four patients and items 6, 13, 14 and 20 by two patients each). None of the patients with lichen planus pigmentosus or melasma reported any additional question to be added to modified of VIS-22.

The modified VIS-22 scores showed moderately good correlation with global question (r = 0.635, P < 0.001) and good correlation with DLQI scores (r = 0.735, P < 0.001) in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Similarly, there was a moderate correlation of modified VIS-22 scores with global question (r = 0.607, P < 0.001) and good correlation with DLQI scores (r = 0.723, P < 0.001) in patients with melasma. DLQI correlated moderately well with global question in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus (r = 0.568, P < 0.001) as well as melasma (r = 0.547, P < 0.001). In patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, the mean modified VIS-22 and DLQI scores were higher for women, those with disease duration > 1 year, progressive disease, affected body surface area < 5% and those who were employed. In addition, the mean modified VIS-22 scores were higher for patients with lichen planus pigmentosus who were unmarried, had 1–2 body sites affected and educated till class 12, while the DLQI scores were higher for those who were married, had >2 body sites affected and educated beyond class 12. None of these differences were statistically significant for either modified VIS-22 or DLQI scores. Among patients with melasma, the mean modified VIS-22 scores were significantly higher for women (P = 0.013), those who were unemployed (P = 0.012) and educated till class 12 (P = 0.006), while the DLQI scores were significantly higher for only women (P = 0.003) and those educated till class 12 (P = 0.023).

Quality-of-life scores in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and comparison with vitiligo and melisma

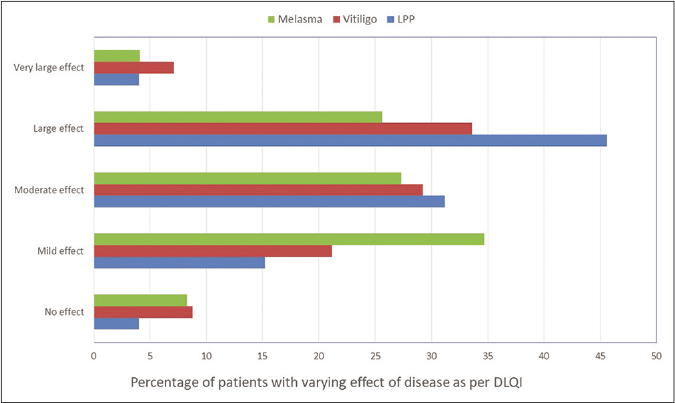

The mean DLQI score in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus was 10.9 ± 5.95, comparable to those with vitiligo (9.73 ± 6.51, P = 0.169) but significantly higher than melasma (8.39 ± 5.92, P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean modified VIS-22 score in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus (26.82 ± 11.89) was also comparable to the VIS-22 scores in patients with vitiligo (25.82 ± 14.03, P = 0.66) but was significantly higher than those with melasma (18.87 ± 11.84, P < 0.001). The mean VIS-22 scores in patients with vitiligo were significantly higher than melasma (P < 0.001), but not DLQI scores (P = 0.167). As per the DLQI scores [Figure 1], 49.6% (n = 62/125) patients with lichen planus pigmentosus had large or very large effect of the disease on life as compared to 40.7% (n = 46/113) patients with vitiligo (P = 0.168) and 29.8% (n = 36/121) patients with melasma (P < 0.001). The difference between patients with vitiligo and melasma almost reached statistical significance (P = 0.08).

- DLQI scores showing the “effect of disease on life” of patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma

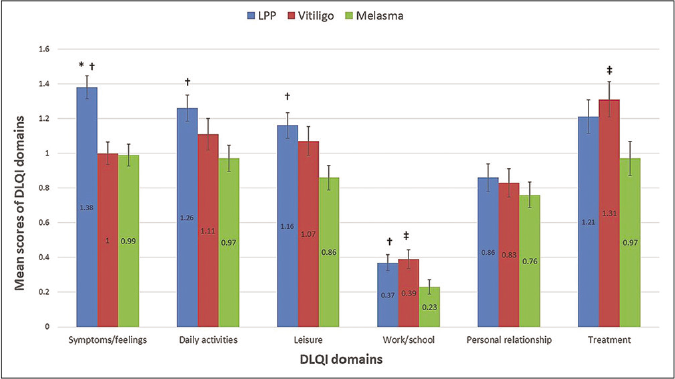

Among the DLQI domains, patients with lichen planus pigmentosus had the highest scores were for “symptoms and feelings” (1.39 ± 0.73), “daily activities” (1.26 ± 0.83) and “treatment” (1.21 ± 1.09). Lichen planus pigmentosus had a significantly higher impact on “symptoms and feelings” compared with both vitiligo and melasma (both P < 0.001). Lichen planus pigmentosus also had a higher effect on “daily activities” (P = 0.015), “leisure” (P = 0.006) and “work and school” (P = 0.024) as compared to melasma. Patients with vitiligo had higher mean scores than melasma in all DLQI domains, but the difference was statistically significant only for “work and school” (P = 0.013) and “treatment” (P = 0.013) domains [Figure 2].

- Mean scores with error bars (standard error of means) of DLQI domains in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma (p < 0.05 * between lichen planus pigmentosus and vitiligo, † between lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma, ‡ between vitiligo and melasma)

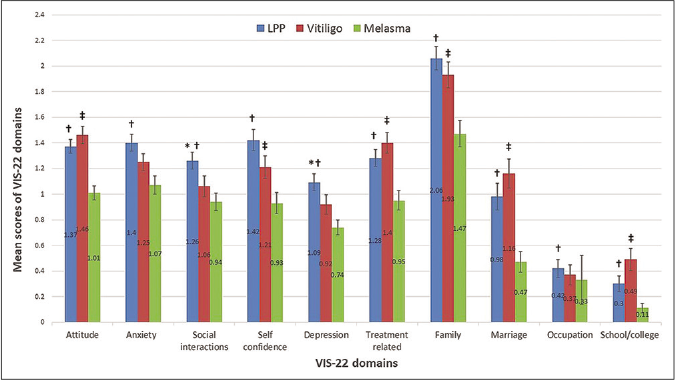

The highest mean scores of VIS-22 domains in lichen planus pigmentosus were obtained for “family” (2.06 ± 1.02), followed by “self-confidence” (1.42 ± 0.92), “anxiety” (1.40 ± 0.75), “attitude” (1.37 ± 0.6) and “treatment” (1.28 ± 0.73). Patients with lichen planus pigmentosus had significantly higher mean scores for “social interactions” (P = 0.02) and “depression” (P = 0.04) domains than vitiligo. In addition, the mean scores for “anxiety,” “self-confidence,” “family” and “occupation” in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus were higher than vitiligo, and lower for “attitude,” “marriage,” “treatment” and “school or college” domains, but these differences were not statistically significant [Figure 3]. Patients with melasma had a lower score in every VIS-22 domain compared to both lichen planus pigmentosus (all P < 0.05) and vitiligo (P < 0.05 for “attitude,” “self-confidence,” “treatment,” “family,” “marriage” and “social or college” domains).

- Mean scores with error bars (standard error of means) of modified VIS-22 / VIS-22 domains in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma (p < 0.05 * between lichen planus pigmentosus and vitiligo, † between lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma, ‡ between vitiligo and melasma)

Factors influencing the quality of life in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus

The results of univariate logistic regression and simple linear regression analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified female gender (OR 2.97, 95% CI: 1.12–7.89, P = 0.03) to be associated with large or very large effect on life as per global question scores. As per DLQI scores, female gender (OR 2.25, 95% CI: 0.85–5.90, P = 0.09), married patients (OR 2.07, 95% confidence interval: 0.87–4.92, P = 0.09) and education higher than class 12 (OR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.17–1.08, P = 0.07) were shown to have a directional trend towards an association with large or very large effect on life, but did not reach statistical significance. Multiple linear regression analysis identified female gender (β = 2.76, 95% CI: 0.09–5.43, P = 0.04) to be associated with an impairment in the quality of life as per DLQI scores, while younger age (β = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.03–0.36, P = 0.09) and increasing disease duration (β = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.06–0.76, P = 0.09) showed a directional trend toward an association with impaired quality of life as per modified VIS-22 scores, but did not reach statistical significance.

| Variables | DLQI score (0-10) (%) | DLQI score (11-30) (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | GQ score (0-2) (%) | GQ score (3-4) (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 44/63 (69.8) | 49/62 (79) | 1.63 (0.72-3.67) | 0.241 | 37/58 (63.8) | 56/67 (83.6) | 2.89 (1.25-6.69) | 0.013 |

| Disease duration >1 year | 47/63 (74.6) | 48/62 (77.4) | 1.17 (0.51-2.65) | 0.713 | 45/58 (77.6) | 50/67 (74.6) | 0.85 (0.37-1.94) | 0.699 |

| Progressive disease | 32/63 (50.8) | 30/62 (48.4) | 0.91 (0.45-1.83) | 0.788 | 27/58 (46.5) | 35/67 (52.2) | 1.25 (0.62-2.54) | 0.526 |

| BSA >5% | 18/56 (32.1) | 20/60 (33.3) | 1.05 (0.48-2.29) | 0.891 | 13/52 (25) | 25/64 (39) | 1.92 (0.86-4.30) | 0.111 |

| >2 sites affected | 19/63 (30.2) | 20/62 (32.3) | 1.10 (0.52-2.35) | 0.800 | 19/58 (32.8) | 20/67 (29.9) | 0.87 (0.41-1.86) | 0.726 |

| Married | 35/63 (55.6) | 45/62 (72.6) | 2.04 (0.96-4.32) | 0.062 | 35/58 (60.3) | 45/67 (67.2) | 1.28 (0.61-2.69) | 0.504 |

| Education >12 class | 39/51 (76.5) | 31/54 (57.4) | 0.41 (0.18-0.96) | 0.041 | 30/50 (60) | 40/55 (72.3) | 1.78 (0.78-4.04) | 0.169 |

| Employed | 24/59 (40.7) | 26/61 (42.6) | 1.08 (0.52-2.22) | 0.829 | 28/55 (50.9) | 22/65 (33.8) | 0.49 (0.23-1.03) | 0.060 |

BSA: bovine serum albumin, DLQI: dermatology life quality index, CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio, GQ: global question

| Variables | DLQI score | mVIS-22 score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | −0.24 (−0.12-0.07) | 0.62 | −0.17 (−0.36-0.01) | 0.07 |

| Women | 2.01 (−0.38-4.41) | 0.09 | 3.19 (−1.61-8.01) | 0.19 |

| Disease duration | 0.13 (−0.07-0.33) | 0.19 | 0.36 (−0.51-0.76) | 0.08 |

| Progressive disease | 0.44 (−1.66-2.56) | 0.67 | 0.04 (−4.18-4.27) | 0.98 |

| BSA | 0.02 (−0.08-0.13) | 0.66 | 0.07 (−0.13-0.29) | 0.48 |

| Number of sites | 0.27 (−0.64-1.18) | 0.56 | 0.71 (−1.10-2.52) | 0.43 |

| Married | 1.79 (−0.39-3.97) | 0.11 | −1.44 (−5.84-2.95) | 0.52 |

| Education >12 class | −1.41 (−3.83-1.00) | 0.25 | 0.84 (−4.04-5.73) | 0.73 |

| Employed | 0.43 (−1.76-2.61) | 0.70 | 1.16 (−3.17-5.51) | 0.59 |

BSA: body surface area, DLQI: dermatology life quality index, mVIS-22: modified VIS-22, CI: confidence interval

Discussion

We found that about half (49.6% as per DLQI, 53.6% as per global question) of the patients with lichen planus pigmentosus reported large or very large disease-related effect on their quality of life. The significant impact of lichen planus pigmentosus on the quality of life was also reflected in their mean DLQI score of 10.9, which corresponds to “a large effect on life.” A previous study from India reported that about 42% patients with lichen planus pigmentosus (n = 7) and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis (n = 10) had large effect on the quality of life as estimated by DLQI.2 The mean DLQI score of 9.73 and VIS-22 score of 25.82 in patients with vitiligo were comparable to previous Indian studies,12-14 while the mean DLQI score of 8.39 in patients with melasma is slightly higher than that reported previously (4.5–6.02).15,16

It is interesting to note that the overall psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus was comparable to vitiligo, despite the stark contrasts in the pigmentary alteration. The adverse effect of vitiligo on patient lives is well recognized. There are several misconceptions prevalent in our society about vitiligo, chief being that it is contagious or occurs as a punishment for past sins. It is often confused with leprosy leading to social ostracism of not only the patient but also the family members.17 Lichen planus pigmentosus does not suffer from such sociocultural stigmas, and it is likely that the poor quality of life in these patients is attributable only to the cosmetically disfiguring facial involvement. DLQI and VIS identified some differences on how lichen planus pigmentosus and vitiligo affect the patients’ lives. For example, “symptoms and feelings” domain of DLQI was affected significantly more in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus as compared to vitiligo. About a third of patients with lichen planus pigmentosus can be symptomatic (itching, burning), while patients with vitiligo are usually not.18,19 Modified version of VIS-22 identified family, self-confidence, anxiety, attitude and treatment as the most affected domains by lichen planus pigmentosus. Patients with lichen planus pigmentosus were likely to be distressed by the constant advice regarding treatment from family members, felt embarrassed when meeting new people, were preoccupied with thoughts about their disease, worried about the spread of lesions and were bothered by the amount of money spent on its treatment. The effect of lichen planus pigmentosus and vitiligo on different VIS-22 life domains was largely similar, except for “social interactions” and “depression” domains which were affected more in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus.

Notably, quality of life in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus was significantly more affected than those with melasma. Patients with lichen planus pigmentosus scored higher than those with melasma for all the domains of DLQI and modified VIS-22. Though both lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma are disorders of hyperpigmentation, skin discoloration in lichen planus pigmentosus is darker, more conspicuous and poorly responsive to treatment, which might cause a greater effect on life.

Women were more likely to have a significant impairment in quality of life due to lichen planus pigmentosus. Studies on vitiligo and melasma have also shown women to be more affected than men, probably because of a greater cosmetic concern.14,20 Younger age, marriage and increasing disease duration tended to have an association with poor quality of life, while patients with higher education tended to have lesser disease effect.

Limitations

Since the study was conducted at a tertiary-care center, we might have included more severely distressed patients. The external validity of our results needs to be tested in other settings. In the absence of a validated disease-specific quality-of-life instrument for lichen planus pigmentosus or for pigmentary disorders in general, DLQI was used. Skin discoloration impact questionnaire, a short five-question instrument has been used in hyperpigmentary disorders by some authors; however, it is not validated and detailed information on its psychometric properties is not available.1,21 We attempted to address this lacuna by including a modified VIS-22 as an additional quality-of-life measure, after testing its face and content validity in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus and melasma, and demonstrating a moderately good criterion validity and good convergent validity. The differences in the overall disease burden and various domains between lichen planus pigmentosus, vitiligo and melasma were better brought forth by modified VIS-22 / VIS-22 than DLQI. Further, modified VIS-22 provided richer information than DLQI regarding certain life domains such as anxiety, attitude, self-confidence, social interactions and depression, though it lacked a symptoms domain relevant to patients with lichen planus pigmentosus.

Conclusion

Lichen planus pigmentosus has a significant negative impact on the quality of life. The psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus is quantitatively similar to that of vitiligo but much greater than that of melasma. Clinicians should take care to address this important, yet often overlooked, aspect of lichen planus pigmentosus which may influence the decision-making process regarding treatment. Patients with lichen planus pigmentosus are likely to benefit from a more holistic approach towards their disease.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project received the IADVL-L’Oreal Indian Hair and Skin research Grant 2018.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prevalence of pigmentary disorders and their impact on quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:164-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with acquired pigmentation: An observational study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1293-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patch testing and histopathology in Thai patients with hyperpigmentation due to Erythema dyschromicum perstans, Lichen planus pigmentosus, and pigmented contact dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2014;32:185-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopy and patch testing in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus on face: A cross sectional observational study in fifty Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:656-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatoscopic evaluation and histopathological correlation of acquired dermal macular hyperpigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:1395-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A global consensus statement on ashy dermatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation, and Riehl's melanosis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:263-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashy dermatosis, lichen planus pigmentosus and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis: Are we splitting the hair? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:470-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everything is in the name: Macular hyperpigmentation of uncertain etiology or acquired dermal macular hyperpigmentation of varied etiologies? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:85-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatology life quality index (DLQI) a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measurement properties of the Vitiligo Impact Scale 22 (VIS 22), a vitiligo specific quality of life instrument. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1084-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What do VIS 22 scores mean? Studying the clinical interpretation of scores using an anchor based approach. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:580-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: An analysis of the dermatology life quality index outcome over the past two decades. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:608-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of melasma on the quality of life in a sample of women living in Singapore. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:21-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with melasma in Turkish women. Dermatol Reports. 2017;9:7340.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The psychosocial impact of vitiligo in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:679-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A clinico demographic study of 344 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus seen in a tertiary care center in India over an 8 year period. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:245-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improved quality of life with effective treatment of facial melasma: The pigment trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:377-81.

- [Google Scholar]