Translate this page into:

Human leukocyte antigen Class II alleles associated with acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizo patients: A case-control study

Corresponding author: Dr. Lucia Rangel-Gamboa, Department of Ecology of Pathogenic Agents, Division of Investigation, Hospital General Dr. Manuel Gea González, México City, México. draluciaragel@yahoo.com.mx

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Roldan-Marin R, Rangel-Gamboa L, Vega-Memije ME, Hernández-Doño S, Ruiz-Gómez S, Granados J. Human leukocyte antigen Class II alleles associated with acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizo patients: A case-control study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:608-14.

Abstract

Background

Melanoma is an aggressive cutaneous cancer. Acral lentiginous melanoma is a melanoma subtype arising on palms, soles, and nail-units. The incidence, prevalence and prognosis differ among populations. The link between expression of major histocompatibility complex Class II alleles and melanoma progression is known. However, available studies report variable results regarding the association of melanoma with specific HLA Class II loci.

Aims

The aim of the study was to determine HLA Class II allele frequencies in acral lentiginous melanoma patients and healthy Mexican Mestizo individuals.

Methods

Eighteen patients with acral lentiginous melanoma and 99 healthy controls were recruited. HLA Class II typing was performed based on the sequence-specific oligonucleotide method.

Results

Three alleles were associated with increased susceptibility to develop acral lentiginous melanoma, namely: HLA-DRB1*13:01; pC = 0.02, odds ratio = 6.1, IC95% = 1.4–25.5, HLA-DQA1*01:03; pC = 0.001, odds ratio = 9.3, IC95% = 2.7–31.3 and HLA-DQB1*02:02; pC = 0.01, odds ratio = 3.7, IC95% = 1.4–10.3.

Limitations

The small sample size was a major limitation, although it included all acral lentiginous melanoma patients seen at the dermatology department of Dr. Manuel Gea González General Hospital during the study period.

Conclusion

HLA-DRB1*13:01, HLA-DQB1*02:02 and HLA-DQA*01:03 alleles are associated with increased susceptibility to develop acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizo patients.

Keywords

Acral lentiginous melanoma

human leukocyte antigen Class II

human leukocyte antigen-DQA1*01:03

human leukocyte antigen-DQB1*02:02

human leukocyte antigen-DRB1*13:01

skin tumour

melanoma

Plain Language summary

The incidence of skin cancers has been rising in recent decades and melanoma is the most aggressive among these. Melanomas include four genetic and clinical variants. One rare variant is acral lentiginous melanoma, a subtype arising from palms, soles, and nail units. The acral lentiginous melanoma incidence, prevalence and prognosis differ among populations. Melanoma progression has been linked to different expression of major histocompatibility complex class II proteins. However, the available literature reports variable findings regarding the melanoma association with specific HLA Class II loci. This study compares HLA Class II allele frequencies in acral lentiginous melanoma Mexican Mestizo patients with the frequencies presented in healthy individuals. Three alleles (HLA-DRB1*13:01, HLA-DQA1*01:03 and HL-DQB1*02:02) were found to confer susceptibility to develop acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizo patients. HLA susceptibility alleles differ among melanoma subtypes, which suggests differences in the immunopathological mechanism. Potentially, HLA typing could be useful to discriminate between melanoma subtypes and could possibly help in guiding the treatment plan.

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is a relatively common skin cancer with different clinical subtypes that vary with respect to progression and clinical presentation.1,2 The rarest type of melanoma is acral lentiginous melanoma; this melanoma variant occurs mainly on the palms, soles, and nail units.3 It begins as a flat patch of discoloured skin that may enlarge slowly over time; it can become invasive and spread as the condition advances. Usually, this entity is diagnosed at advanced stages. Thus, prognosis tends to be worse than with other subtypes of melanoma.4-6

Melanoma is considered an immunogenic malignancy. In an idyllic state, antigen-presenting cells lead to the activation of effector memory T-cells in the lymph nodes that mediate anti-tumour effects at the cancer site, producing new antigens from destroyed malignant cells and creating a tumour-immunity cycle.7 One of the contributory factors to melanoma progression is the failure of melanoma cells expressing HLA Class II molecules to process oxidised or cysteinylated peptides.8 This phenomenon leads to a modified epitope presentation to CD4+ T-cells and a resultant absence of immune response against the tumour.9 HLA-DR mediated signalling is another factor that plays a role in melanoma progression, increasing the migration and invasion of melanoma cells.10

HLA-DR mediated signalling is strongly influenced by the high polymorphism of these molecules.10 Importantly, the variability and richness of HLA molecules in Mexican Mestizos are strongly influenced by admixture;11 and in many cases, the introduced and fixed alleles have been responsible for susceptibility to different diseases. However, the specific alleles which generate susceptibility and change signalling in melanoma cells are not yet described for acral lentiginous melanoma. Consequently, this work aims to determine the frequencies of major histocompatibility complex Class II alleles, namely, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DQA1 in Mexican Mestizo patients with acral lentiginous melanoma and compare them with ethnically matched healthy controls.

Methods

Subjects

Eighteen ethnically Mexican Mestizo patients with acral lentiginous melanoma were included. Mestizos are the result of admixture, mostly between Amerindians and Spaniards; currently, they represent practically 93% of Mexican population.12 The diagnosis of acral lentiginous melanoma was based on clinical evaluations as well as histologic criteria. Tumour site and histology were coded according to the World Health Organization classification of tumours.13 Recruited patients had a histologic diagnosis of acral lentiginous melanoma; ICD code 8744.5 The presence of other cancers or diseases already linked to HLA alleles, mainly autoimmune diseases, was considered an exclusion criterion. All patients were above 18 years old, and they were recruited during a three-year period between 2004 to 2007, from the dermatology outpatient clinics at Dr. Manuel Gea González General Hospital in Mexico City. As a control group, 99 healthy unrelated Mexican admixed individuals were studied.

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of Dr. Manuel Gea González General Hospital approved the protocols for genetic studies (registration number 06-39-2006). All subjects were informed about the research objectives and procedures related to this study and provided written informed consent before recruitment to this study. Declining to participate did not affect their medical treatment. All procedures were performed with due respect for human rights in keeping with the Helsinki declaration.14

HLA typing

Genomic DNA from all study subjects was obtained and purified from peripheral blood leukocytes, according to Miller’s salting-out method.15 Blood was collected by a single peripheral venipuncture, according to the current guidelines and procedures approved by the Internal Review Boards of the Dr. Manuel Gea González General Hospital. The HLA-DRB1, -DQB1 and -DQA1 loci were genotyped based on the hybridisation of labelled single-stranded polymerase chain reaction products to sequence-specific oligonucleotides. The LifeCodes HLA typing kit using the Luminex platform (GenProbe Transplant Diagnostics, Inc., Stamford, CT, USA) was used, in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. Data were analysed using the Quicktype for LifeCodes version 3.0 software to determine the HLA alleles.

Statistical analysis

Each allele was evaluated separately with the X2 method using the Epi Info™ v7.2, Stat Calc, tables (2×2×N) option. Epi Info™ software is provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.16 A P-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference between HLA allele frequencies in patients compared to healthy individuals. The P-values were also corrected using the Bonferroni method (for allele frequencies, multiplying the original P-value by the number of alleles, included in the EpiInfo algorithm). The risk factors were expressed as odds ratios.

Results

Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics of acral lentiginous melanoma patients

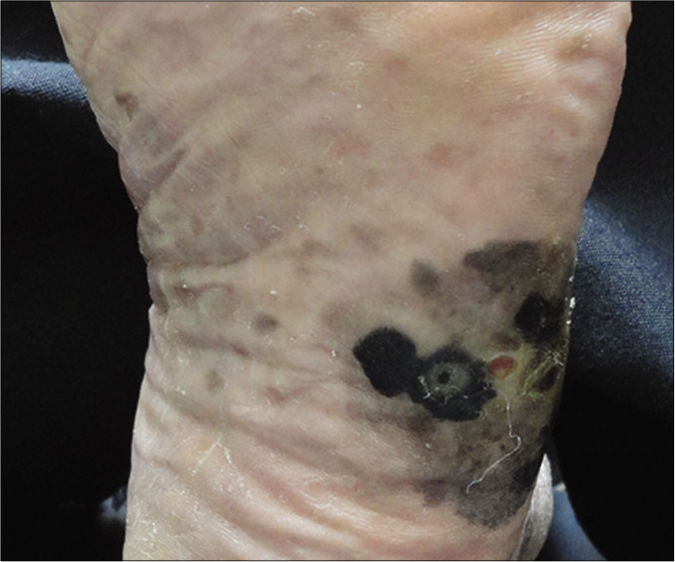

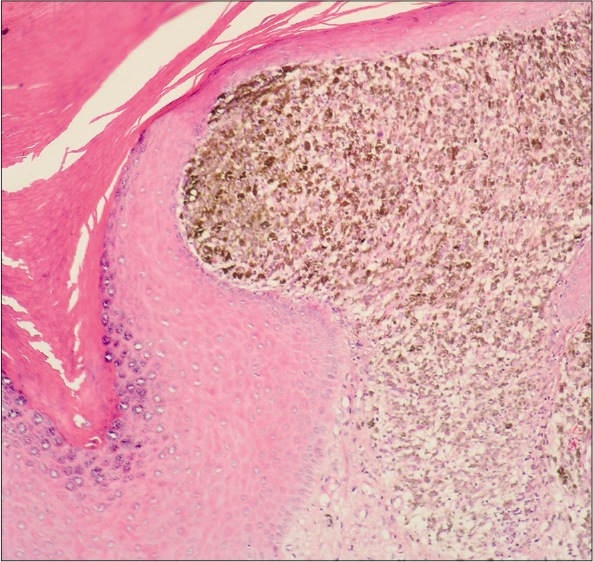

Eighteen patients with acral lentiginous melanoma were diagnosed by clinical [Figure 1] and histopathological criteria [Figure 2]. The mean age at diagnosis was 56 years; females outnumbered males with a ratio of 2.6:1. Lesions were most often located on the lower extremities, in 10/18 of cases (55.5%).

- Acral lentiginous melanoma on the lateral aspect of the left foot showing irregularly bordered and variable pigmentation with a slightly centre ulcerated lesion

- Acral lentiginous melanoma, showing epidermis with acanthosis, in papillary dermis atypical melanocytes with melanin granules and large nuclei. (H&E, ×100)

HLA-DRB1*13:01, -DQA1*01:03 and -DQB1*02:02 are susceptibility alleles for acral lentiginous melanoma

The HLA alleles, which showed higher frequencies among acral lentiginous melanoma patients compared with healthy individuals, were HLA-DQA1*01:03 (pC = 0.001, odds ratio = 9.3, IC95% = 2.7–31.3), HLA-DQB1*02:02 (pC = 0.01, odds ratio = 3.7, IC95% = 1.4–10.3) and HLADRB1*13:01 (pC = 0.02, odds ratio = 6.1, IC95% = 1.4–25.5 [Tables 1-3].

| HLA-DQA1 Alleles | Patients | Healthy Individuals | pCa | OR | 95% IC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=18 n=36 |

N=99 n=198 |

|||||||

| N | af | n | af | |||||

| DQA1*03 | 12 | 0.333 | 51 | 0.258 | 0.460 | 1.4 | 0.67 | 3.09 |

| DQA1*01:03 | 7 | 0.194 | 5 | 0.025 | 0.0001 | 9.32 | 2.77 | 31.31 |

| DQA1*04:01 | 5 | 0.139 | 33 | 0.167 | 0.865 | 0.8 | 0.29 | 2.23 |

| DQA1*01:01 | 3 | 0.083 | 11 | 0.056 | 0.791 | 1.5 | 0.41 | 5.84 |

| DQA1*01:02 | 3 | 0.083 | 14 | 0.071 | 1.000 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 4.39 |

| DQA1*05:02 | 3 | 0.083 | 5 | 0.025 | 0.206 | 3.5 | 0.80 | 15.39 |

| DQA1*05:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 32 | 0.162 | 0.160 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 1.33 |

| DQA1*02:01 | 1 | 0.028 | 22 | 0.111 | 0.215 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 1.75 |

N: Number of individuals, n: Number of alleles, af: Allele frequency,

| HLA-DQB1 Alleles | Patients | Healthy Individuals | pCa | OR | 95% IC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=18 n=36 |

N=99 n=198 |

|||||||

| n | af | n | af | |||||

| DQB1*04:02 | 9 | 0.250 | 33 | 0.167 | 0.336 | 1.7 | 0.72 | 3.87 |

| DQB1*02:02 | 7 | 0.194 | 12 | 0.060 | 0.01 | 3.7 | 1.36 | 10.28 |

| DQB1*03:02 | 5 | 0.139 | 48 | 0.242 | 0.251 | 0.5 | 0.19 | 1.37 |

| DQB1*03:01 | 3 | 0.083 | 33 | 0.166 | 0.306 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 1.57 |

| DQB1*06:03 | 3 | 0.083 | 4 | 0.020 | 0.130 | 4.4 | 0.94 | 20.60 |

| DQB1*05:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 9 | 0.045 | 1.000 | 1.2 | 0.26 | 5.97 |

| DQB1*06:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 2 | 0.011 | 0.216 | 5.8 | 0.79 | 42.32 |

| DQB1*06:02 | 2 | 0.055 | 12 | 0.060 | 1.000 | 0.9 | 0.20 | 4.26 |

| DQB1*02:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 31 | 0.156 | 0.180 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 1.39 |

| DQB1*06:09 | 1 | 0.028 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||

N: Number of individuals, n: Number of alleles, af: Allele frequency,

| HLA-DRB1 Alleles | Patients | Healthy Individuals | pCa | OR | 95% IC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=18 n=36 |

N=99 n=198 |

|||||||

| N | af | n | af | |||||

| DRB1*08:02 | 9 | 0.250 | 30 | 0.150 | 0.224 | 1.9 | 0.80 | 4.36 |

| DRB1*07:01 | 7 | 0.194 | 22 | 0.111 | 0.262 | 1.9 | 0.76 | 4.93 |

| DRB1*04:07 | 5 | 0.138 | 21 | 0.106 | 0.773 | 1.4 | 0.48 | 3.87 |

| DRB1*13:01 | 4 | 0.111 | 4 | 0.020 | 0.02 | 6.1 | 1.40 | 25.50 |

| DRB1*15:01 | 4 | 0.111 | 9 | 0.045 | 0.235 | 2.6 | 0.76 | 9.03 |

| DRB1*14:01 | 3 | 0.083 | 6 | 0.030 | 0.293 | 2.9 | 0.69 | 12.21 |

| DRB1*01:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 7 | 0.035 | 0.913 | 1.6 | 0.32 | 8.06 |

| DRB1*03:01 | 2 | 0.055 | 9 | 0.045 | 1.000 | 1.2 | 0.26 | 5.97 |

N: Number of individuals, n: Number of alleles, af: Allele frequency,

Previous studies have not found a linkage disequilibrium among these three susceptibility alleles which we found increased in acral lentiginous melanoma patients.17 This implies that each allele confers risk separately and the risks are additive. Thus, patients who have more than one susceptibility allele been at a correspondingly greater risk of developing acral lentiginous melanoma, which does not happen when alleles are in linkage disequilibrium. Importantly, any of these alleles are not from native Amerindians.18

Discussion

Melanoma in Mexico has a prevalence of 0.4 per 100 thousand inhabitants.19 However, acral lentiginous melanoma prevalence is not known and limited information has been published about acral lentiginous melanoma and HLA susceptibility alleles. Acral lentiginous melanoma is included as a rare disease in the National Institute of Health Database and Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center.20 Its severity is often the result of the delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis and the fundamental cause of acral lentiginous melanoma is poorly understood. It is not related to sun exposure, unlike other forms of skin cancer.21,22 Major histocompatibility complex expression is known to influence melanoma severity and its response to anti-cancer therapy. However, only few associations have been described between HLA-specific alleles and melanoma and even less is known in this regard for acral lentiginous melanoma.

In this study, we found, three HLA Class II susceptibility alleles, namely, HLA-DRB1*13:01, HLA-DRQB1*02:02 and HLA-DQA1*01:03, which confer high risks for the development of acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizos. HLA-DQA1*01:03 was previously associated with melanoma in the Japanese population.23 However, it is the first time that HLA-DQB1*02:02 and HLADRB1*13:01 have been associated with melanoma in any population. Remarkably, each one of these three alleles confers an independent risk for the development of acral lentiginous melanoma. More importantly, these alleles are not recognized as native of Mexican Amerindians; this fact adds an anthropological angle to the results, which in turn influences the biomedical traits. Therefore, the biomedical, clinical, and anthropological importance of the results is discussed.

The complex ethnic background of Mexicans contributes to the unusual situation where alleles such as HLA-DRB1*13:01 and HLA-DRB1*02:02, found in haplotypes mainly from African and Caucasian populations, respectively, increase the susceptibility of Mexican patients to develop acral lentiginos melanoma. Mexicans are among the population groups with the highest richness of admixture worldwide. This fact affects the biomedical traits and consequently, favours the development of diseases and altered immunological responses in Mexicans,23 as has been seen in other diseases and autoimmune conditions.

The biomedical repercussions chiefly concern the aberrant participation of HLA-DR in melanoma cell signalling, allowing, and enhancing melanoma cell migration and invasion, which has been previously demonstrated.8-10,24 But hitherto, not much was known regarding specific HLA Class II susceptibility alleles for acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexicans. Quite possibly the acral lentiginous variant shares the invasion mechanism modified by HLA-DR that has been described in common melanoma. Besides, recently it has been demonstrated that major histocompatibility complex proteins are determinants of both melanoma prognosis25 as well as its sensitivity to different anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1 and MAPK inhibitors.26,27

Some studies about HLA alleles and susceptibility to melanoma have been inconclusive.28,29 But recently, a Genome-Wide Association Study has confirmed the role of HLA in melanoma.28 In this study, HLA-DQA1*01:03 has been associated with susceptibility to develop acral lentiginous melanoma, which has also been confirmed in Japanese patients (P = 0.013, odds ratio = 2.4).23 Moreover, the HLA-DQA1 locus has been associated with melanoma in Spaniards,30,31 but the risk alleles found were different from those found in Mexicans. In our study, HLADQA1*01:03 presented a strong statistical association with acral lentiginous melanoma patients with carriers having a more than nine-fold risk of developing the disease.

The second allele which presented a significant statistical association with acral lentiginous melanoma in our study was HLA-DQB1*02:02, imparting an almost four-fold increased risk of developing this type of melanoma. HLA-DQB1 locus has been studied in Italian melanoma patients; some alleles were found more frequently in patients, but the results were not statistically significant.31 Interestingly, other studies have observed that patients with localised melanoma who carried HLA-DQB1*03:01 presented an increased risk of developing recurrent disease compared with stage-matched patients who lacked this allele.33-35

The third allele which presented strong statistical association with acral lentiginous melanoma in our studied patients was HLA-DRB1*13:01, conferring a more than six-fold increased risk of developing the disease. Studies about the -DRB1 locus have been performed in different groups of melanoma patients. A study involving Italian melanoma patients found an increased frequency HLA-DRB1*11:01 but without reaching statistical significance.32 Nevertheless, another study noticed that HLA-DRB1*11:01 was the strongest predictor of melanoma recurrence. In addition, these patients showed increased levels of IFN-gamma compared with patients lacking this allele,36 which could be contributory to recurrence.

Regarding anthropological aspects, the presence of three foreign HLA Class II alleles in Mexicans could be explained on the basis that these susceptibility alleles were introduced and fixed because of an advantage against infections. However, antigen presentation by these alleles is not favourable and probably permits acral lentiginous melanoma cells to escape immune responses.

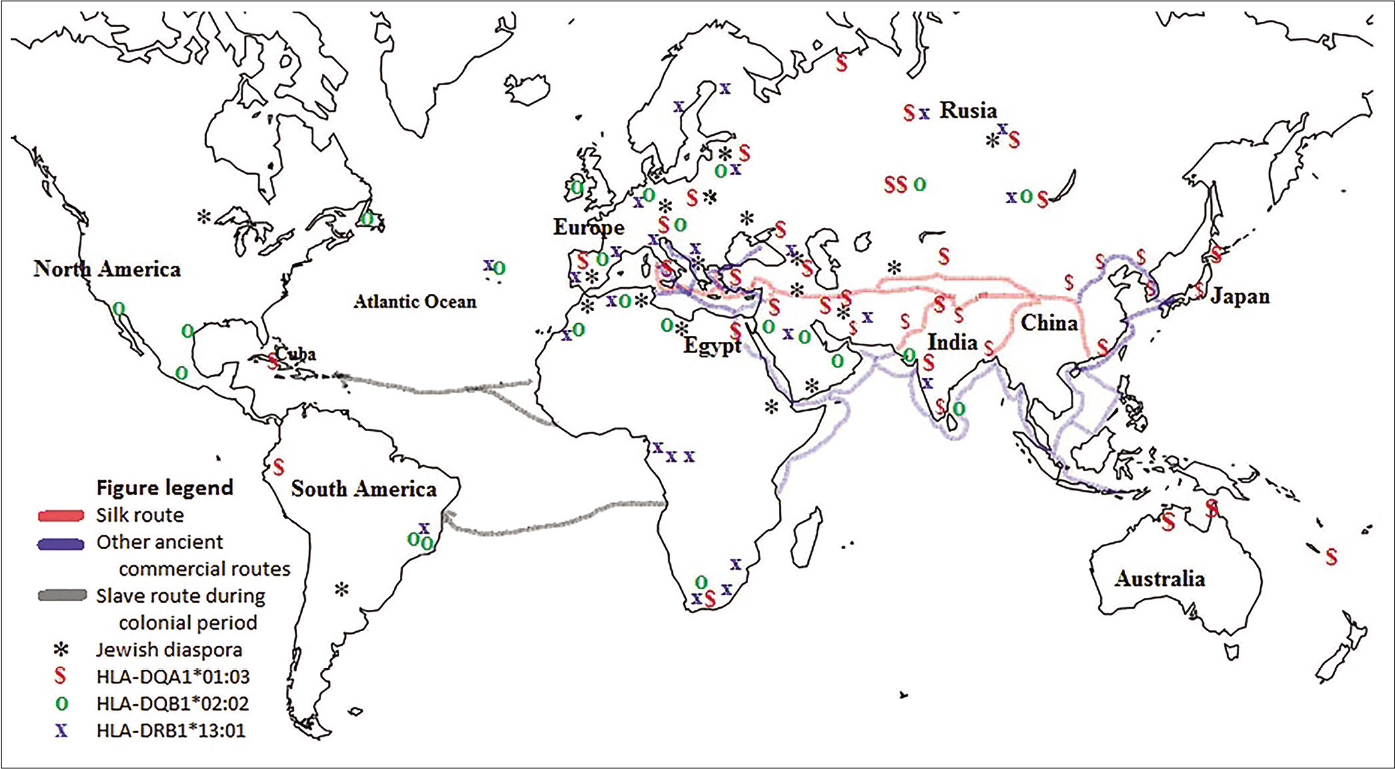

Human migration dynamics could explain the increased frequency of the susceptibility alleles in Mexican Mestizo acral lentiginous melanoma patients. The HLA region is commonly used in anthropology studies because the allele and haplotype distributions at these loci vary widely among ethnic groups.37,38 Thus, according to the data available in allele frequency net database,18 the allele HLA-DQA1*01:03 is most prevalent in the region along the ancient commercial route called the “Silk Road,”37,39 which is depicted in Figure 3. In contrast, HLA-DQA1*01:03 is found in low frequencies in Amerindian natives [Table 4]. This allele was introduced by Europeans during migrations processes to the Americas.40,41

- World map showing the Silk Road and other ancient commercial routes from east to west and some slave routes from Africa to America used in the colonial period. Also marked are regions populated by the Jewish diaspora and regions with high prevalence (≥9%) of HLA-DQA1*01:03, HLA-DQB1*02:02 and HLA-DRB1*13:01 alleles

| Allele | Populations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acral lentiginous melanoma patients | Mexican Mestizo (control group) | Maya Mazatecans Mixtec Nahuas Tarahumara17,20,21,26,27,33 | Aymaras (Bolivia), Mapuche (Araucanian Chile) and Urros (Titikaka lake, Peru) 34,35 | Japanese31 | Italian | Spain29,30 | Finland36 | Jewish22-25 | ||

| Ashkenazi | Non-Ashkenazi | |||||||||

| DQA1*01:03 | 0.194 | 0.025 | 0.035 | ? | 0.272 | 0.059– 0.113 |

0.074– 0.104 |

? | 0.174–0.181 | 0.149†–0.225 |

| DQB1*02:02 | 0.194 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.077 | 0.175 | 0.029 | 0.333a | 0.423a |

| DRB1*13:01 | 0.111 | 0.020 | 0.000–0.011 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.083 | 0.090 | 0.035–0.075 | 0.089†–0.092 |

†Moroccan Jews. aIn these cases just HLA-DQB1*02 information was available, HLA: Human leukocyte antigen

As for HLA-DQB1*02:02, it is common in Europe. High allele frequencies are observed in Portugal and Spain, ranging from 0.175–0.178. In Mexican Mestizos, this allele has been previously identified in haplotypes of Caucasian origin.17 In this study, the frequency of this allele in Mexican Mestizo acral lentiginous melanoma patients is 0.194, which is like its frequency in the Caucasian population. However, the allele frequency is diminished in Mexican Mestizo healthy individuals being 0.060.17,42

The third allele of interest, HLA-DRB1*13:01 has been reported at a lower frequency of 0.020 in the native Amerindian population. HLA-DRB1*13:01 appearance in Amerindians is considered to be a product of admixture with Spaniard conquerors.39,43 However, the highest frequencies of this allele have been found in African haplotypes.17

Acral lentiginous melanoma is the rarest type of melanoma, but is most common in non-Caucasian ethnicities, with 15% presenting in Hispanics and only 2–8% in Caucasians. However, it is interesting that one of the main alleles imparting susceptibility to Mexicans is Caucasian, which suggests a genetic interaction with Mexican genes resulting in disease, which manifests much less often in Caucasians. Importantly, the Mexican Americans do not develop acral lentiginous melanoma.

More significantly, the medical implication of this study is that, although informally, medicine in Mexico is increasingly taking the ethnic aspect more seriously in suspecting a disease involving a genetic component. Gradually, ethnicity is taking its place as a novel criterion in the screening and decision algorithm of some diseases.44

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, this study included every single acral lentiginous melanoma patient seen at the outpatient dermatology clinic at Dr. Manuel Gea González General Hospital during the three-year study period. Moreover, this dermatology department is a national referral centre for dermatological diseases for southern and central states of Mexico.

Conclusion

This study shows the role of HLA alleles in susceptibility to develop acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican Mestizos. The presence of HLA-DQA1*01:03, HLA-DRB1*02:02 and HLADRB1*13:01 increased the risk of acral lentiginous melanoma in this study. These differ from the alleles found in other studies of HLA and common melanoma. The differences in susceptibility alleles could indicate important differences in the immunopathological mechanisms; or besides the differences could be attributable to the ethnic and admixture background.

Adding the determination of HLA Class II to the battery of genetic studies conducted on acral lentiginous melanoma in Mexican patients when there are doubts about the melanoma diagnosis could be beneficial.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Evolving concepts in melanoma classification and their relevance to multidisciplinary melanoma patient care. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:124-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acral cutaneous melanoma in caucasians: Clinical features, histopathology and prognosis in 112 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:275-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acral lentiginous melanoma: Incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanoma in Mexico: Clinicopathologic features in a population with predominance of acral lentiginous subtype. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:4189-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and treatment of cutaneous melanoma of the foot. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43:59-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulatory T cells in melanoma: the final hurdle towards effective immunotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e32-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Absence of gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase in melanomas disrupts T cell recognition of select immunodominant epitopes. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1267-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insights into the role of GILT in HLA class II antigen processing and presentation by melanoma. J Oncol. 2009;2009:142959.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The HLA-DR mediated signalling increases the migration and invasion of melanoma cells, the expression and lipid raft recruitment of adhesion receptors, PD-L1 and signal transduction proteins. Cell Signal. 2017;36:189-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The immunogenetic diversity of the HLA system in Mexico correlates with underlying population genetic structure. Hum Immunol. 2020;81:461-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic admixture, relatedness, and structure patterns among Mexican populations revealed by the Y-chromosome. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2008;135:448-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. In: 4th ed. Vol 11. Geneva: IARC Publication; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epi Info™, a Database and Statistics Program for Public Health Professionals Atlanta, GA, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- HLA class I and class II conserved extended haplotypes and their fragments or blocks in Mexicans: Implications for the study of genetic diversity in admixed populations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74442.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allele frequency net database (AFND) 2020 update: gold-standard data classification, open access genotype data and new query tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D783-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous melanoma in Latin America: The need for more data. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2011;30:431-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. 2021. Available from: https://beta.rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/9570/acral-lentiginous-melanoma

- [Google Scholar]

- Acral lentiginous melanoma: A clinicoprognostic study of 126 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:561-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:765-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular genetic analysis of HLA class II alleles in Japanese patients with melanoma. Tissue Antigens. 1997;49:466-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanoma-specific MHC-II expression represents a tumour-autonomous phenotype and predicts response to anti-PD-1/ PD-L1 therapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10582.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA class Ia and Ib molecules and FOXP3+ TILs in relation to the prognosis of malignant melanoma patients. Clin Immunol. 2017;183:191-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHC proteins confer differential sensitivity to CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade in untreated metastatic melanoma. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar3342.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PD-L1 expression and immune escape in melanoma resistance to MAPK inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6054-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA class I and class II frequencies in patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma from southeastern Spain: the role of HLA-C in disease prognosis. Immunogenetics. 2006;57:926-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hereditary malignant melanoma is not linked to the HLA complex on chromosome 6. Int J Cancer. 1985;36:439-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA class II polymorphisms in Spanish melanoma patients: homozygosity for HLA-DQA1 locus can be a potential melanoma risk factor. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:261-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular genetic analysis of HLA-DR and-DQ alleles in Spanish patients with melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:90-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular analysis of HLA DRB1 and DQB1 polymorphism in Italian melanoma patients. J Immunother. 1998;21:435-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malignant melanoma: relationship of the human leukocyte antigen class II gene DQB1*0301 to disease recurrence in American joint committee on cancer stage I or II. Cancer. 1996;78:758-63.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- HLA-DQB1*0303 and *0301 alleles influence susceptibility to and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma in the British Caucasian population. Tissue Antigens. 1998;52:67-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA-DQB1*0301 association with increased cutaneous melanoma risk. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:510-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presence of the human leukocyte antigen class II gene DRB1*1101 predicts interferon gamma levels and disease recurrence in melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:587-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allele frequency net 2015 update: new features for HLA epitopes, KIR and disease and HLA adverse drug reaction associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D784-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA class II alleles in Amerindian populations: Implications for the evolution of HLA polymorphism and the colonization of the Americas. Hereditas. 1997;127:19-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Origin of mayans according to HLA genes and the uniqueness of Amerindians. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:425-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA genes in Mexican Mazatecans, the peopling of the Americas and the uniqueness of Amerindians. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:405-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of HLA class II alleles and haplotypes in Mexican Mestizo population: comparison with other populations. Immunol Invest. 2010;39:268-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLA class II diversity in seven Amerindian populations. Clues about the origins of the Ache. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62:512-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human genetics. The genetics of Mexico recapitulates Native American substructure and affects biomedical traits. Science. 2014;344:1280-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]