Translate this page into:

Neutrophil extracellular traps and Sweet syndrome

Corresponding author: Dr. Cristina Croia, Immuno-Allergology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Via Roma 67, Pisa 56126, Italy. cristina.croia@med.unipi.it

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Croia C, Dini V, Loggini B, Manni E, Bonadio AG, Romanelli M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and Sweet syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:842-3.

Sir,

A growing body of evidence suggests that skin damage in neutrophilic dermatoses is at least in part mediated by the formation of neutrophilic extracellular traps.1,2

Sweet syndrome, a neutrophilic dermatosis, is characterised by the acute onset of tender nodules and plaques often associated with fever and histologically characterised by a diffuse infiltrate consisting predominantly of mature neutrophils.3 The disease may be idiopathic or, in up to one-third of cases, be associated with haematologic malignancies or drug intake.

Neutrophils can occasionally undergo a unique form of cell death by releasing their nuclear and cytoplasmic content (neutrophils extracellular traps) as a form of protection against external stimuli. Neutrophils extracellular traps have been investigated in different immune-mediated disorders as well as autoimmune diseases, and it has been suggested that they can play an important role in the pathogenesis of cutaneous inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis.4 We recruited four Sweet syndrome patients, of which one patient concomitantly had a B cell lymphoma and one had type 2 diabetes. We studied neutrophils extracellular traps in the tissue as proposed by Brinkman et al., by performing double immunofluorescence for histone/myeloperoxidase (H2B/MPO) in skin biopsies.5 Biopsies from three abscesses and two non-lesional skin were used as controls. We also assessed the rate of spontaneous and stimuli-induced neutrophilic extracellular traps in peripheral neutrophils from the diabetic Sweet syndrome patient and five healthy controls, by performing immunofluorescence for myeloperoxidase on fixed cells.

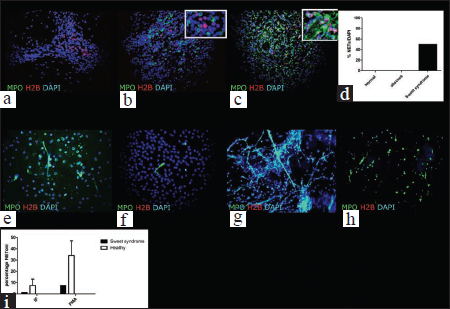

We found that two of the Sweet syndrome skin biopsies displayed a highly increased level of neutrophilic extracellular traps, identified by the co-expression of MPO and H2B in a 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-positive cell [Figs. 1c and d]. Both these patients had comorbidities (diabetes or lymphoma).

- A double immunofluorescence staining shows absence of NETs (indicated by the lack of co-localization of MPO and H2B) in a normal and abscess skin sample (a, b, d). In c a Sweet syndrome skin sample is characterized by scattered NETting cells. The colocalization of the two antigens is better illustrated in the inset in c. Lower percentage of NETting neutrophils were observed in both the immediately fixed (e,f) and PMA stimulated (g,h) neutrophils in Sweet patients (f,h,i) comparted to healthy (e,g,i) patients.

Among the control or abscess biopsies, none were positive for neutrophilic extracellular traps, although a variable level of H2B or MPO expression was found in abscesses and only H2B expression was detected in non-lesional skin [Figs. 1a, b and d]. The absence of netting of neutrophils in the abscess is particularly relevant, indicating that in a very dense infiltrate, neutrophils do not necessarily undergo neutrophilic extracellular trap-osis (NETosis) with a higher rate.

In the patient with Sweet syndrome and diabetes, we also studied the rate of spontaneous (immediately fixed, IF) and induced (by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, PMA) NETosis in peripheral blood neutrophils and lower percentage of NETting neutrophils were observed in both the immediately fixed and PMA stimulated neutrophils in Sweet patients compared to healthy patients. [Figures 1e-i].

Overall, our results indicate that neutrophils may undergo an aberrant level of NETosis in the skin lesions but not in the peripheral blood of Sweet syndrome patients. Aberrant NETosis was observed only in Sweet syndrome associated with disorders like diabetes and lymphoma. These disorders are per se characterised by increased NETosis of peripheral neutrophils. However, the single diabetic patient we analysed had low levels of NETosis in circulating neutrophils and increased levels in skin infiltrating neutrophils. Thus, the role of comorbidities in affecting NETosis in skin infiltrating neutrophils seems limited.

On the contrary, in a previous study, aberrant NETosis was detected in skin lesions of all the pyoderma gangrenosum patients that were studied, irrespective of the coexistence of autoimmune disorders.1,2 Neutrophils extracellular trap are less frequently detected in Sweet syndrome patients compared to pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that, despite a similar neutrophilic infiltrate in the skin, neutrophilic dermatoses may differ in the extent of NETosis.1,2 In pyoderma gangrenosum, the higher number of netting neutrophils is parallel to a higher degree of tissue damage, leading to ulcerative lesions.

Similar results have been reported by Eid et al., analysing a larger cohort of Sweet syndrome patients and a smaller group of pyoderma gangrenosum patients.2

Thus, further studies are necessary on Sweet syndrome patients to identify the mechanisms of neutrophil-induced skin damage, and the role of NETosis in the different subsets of the disease.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as the patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Evaluation of neutrophil extracellular trap deregulated formation in pyoderma gangrenosum. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30:1340-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characterizing the presence of neutrophil extracellular traps in neutrophilic dermatoses. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30:988-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:414.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigating the presence of neutrophil extracellular traps in cutaneous lesions of different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:1348-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunodetection of NETs in paraffin-embedded tissue. Front Immunol. 2016;7:513.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]