Translate this page into:

Application of CL Detect™ rapid test for diagnosis and liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A retrospective analysis from a tertiary care centre in a non-endemic area in India

Corresponding author: Dr. Ruchi Singh, Molecular Biology Laboratory, ICMR-National Institute of Pathology, Safdarjung Hospital Campus, New Delhi, India. ruchisp@gmail.com; ruchisingh.nip@gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Yadav P, Ramesh V, Avishek K, Kathuria S, Khunger N, Sharma S, et al. Application of CL Detect™ rapid test for diagnosis and liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A retrospective analysis from a tertiary care centre in a non-endemic area in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:78-84. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1017_2022

Abstract

Background

Increasing urbanisation has led to the occurrence of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in new areas, which was otherwise localised to endemic areas. Healthcare workers should be made aware of this entity to ensure clinical suspicion of CL and investigations needed to confirm CL. The article describes patients seen at a tertiary hospital in Delhi.

Aims

To establish the utility of the CL Detect Rapid test as a diagnostic tool and the efficacy of Liposomal Amphotericin B (LAmB) for the complete cure of CL patients.

Methods

Data of patients of CL (n = 16) was retrospectively analysed concerning diagnosis and treatment. Diagnosis rested on histopathology, real-time PCR, and CL Detect Rapid Test. Speciation of the parasite was based on the Internal transcribed spacer-I gene. Patients were treated with LAmB (i.v., 5 mg/kg up to three doses, five days apart).

Results

A positivity of 81.3% (95%CI, 54.4–96) was observed for CL Detect Rapid test in comparison with 100% (95%CI, 79.4–100.0) for real-time PCR and 43.8% (95%CI, 19.8–70.1) for microscopy/histopathological examination. L. tropica was the infective species in all cases. All the patients treated with LAmB responded to treatment, and 9/10 patients demonstrated complete regression of lesions, while one was lost to follow-up.

Limitations

It is a retrospective study, and the data includes only confirmed cases of CL at a single centre.

Conclusion

This study highlights the utility of CL Detect as a promising diagnostic tool and the efficacy of LAmB for the complete cure of CL.

Keywords

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

LAmB

CL Detect Rapid test

diagnosis

treatment

Plain Language Summary

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is an infectious disease spread by the bite of infected sandflies. Affected individuals develop skin ulcers and can suffer from severe disfigurement. In recent years, the number of CL cases in non-endemic areas has increased due to increased migration and urbanisation. This article describes CL patients from different parts of India seen at a tertiary hospital in Delhi . This study evaluated the utility of the CL Detect Rapid test as a diagnostic tool and the efficacy of Liposomal Amphotericin B (LAmB) in treating CL patients to cure them completely. The CL detection test correctly identified nearly 80% of confirmed cases of CL. The infective species in these cases was Leishmania tropica. All the patients treated with LAmB responded to treatment, and 9/10 patients demonstrated complete regression of lesions, while one was lost to follow-up. The results of this study indicate that the CL Detect Rapid test is a reliable tool for diagnosing CL. Furthermore, LAmB is an effective treatment for CL, with a high success rate in curing the disease.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), a vector-borne parasitic disease caused by Leishmania, affects the global population with 0.6–1.0 million cases annually.1 In India, regions in and around the Thar desert in Rajasthan are considered endemic for CL. Additionally, cases from other areas, like Himachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir, have been reported over the past two decades.2–4

In the old world, the causative species are L. tropica, L. major and L. aethiopica.1,5 Reports of atypical CL are well documented from Sri Lanka, where the infective species was L. donovani.6 Similarly, atypical CL due to L. donovani has been reported from Himachal Pradesh, India.2

Demonstration of Leishman-Donovan bodies (LDB), a standard test for diagnosis of CL in slit-skin smear from the lesion, has low sensitivity (40–60%) and needs expertise in interpretation.7 Immunological methods are not dependable for diagnosing CL.8 CL Detect™ Rapid Test is qualitative, in vitro immunochromatographic assay that detects peroxidoxin antigen of Leishmania species that has shown considerable sensitivity in detecting CL.7,9,10 Nucleic acid amplification-based methods like PCR, real-time PCR and LAMP have been used to diagnose CL.10,11 Molecular assays targeting parasite-specific Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and heat shock protein (hsp) 70 are used for determining the parasite species.10,12,13

Although CL self-heals, specific treatment can accelerate parasite clearance. Pentavalent antimony is the treatment of choice.14 Miltefosine is an oral drug with good efficacy, but a complete cure in old world CL is not common.15 Amphotericin B (AmB) is reserved for cases of antimony failures. Resistance to antimonials and side effects observed have supported the use of liposomal AmB (LAmB).16,17 Other curative options, including local destructive measures like cryotherapy and heat therapy, require special equipment.18,19 We have shown the utility of the CL Detect Rapid test, a less invasive procedure, as a promising diagnostic tool at the point of care. We also highlight the curative efficacy of LAmB.

Methods

Study population

Data from CL patients (n = 16) in the age range of 6 to 70 years who reported to the Department of Dermatology, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College & Safdarjung Hospital (SJH) during the years 2015–2019 were included, and the relevant clinical details have been tabulated [Table 1]. The disease was termed “localised” when one body region was affected and “disseminated” when more than one part was involved.

| S. No. | Patient’s Age, Sex and place of residence | Extent of Disease and Clinical features | Histopathology | Slit Smear for LDB | CL Strip Test | Speciation | Prior Therapy | Treatment and Outcome | Follow up/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

27, M Rajasthan |

Localised; Upper lip nodule, 1 year |

Thinned-out epidermis. Dense dermal chronic inflammation of lymphohistiocytes and plasma cells. No LDB |

Negative | Positive | L. tropica | Antibiotics |

Intralesional SAG 2ml (200mg) weekly. Lesions subsided after 3 injections. |

Lost to follow-up after 4 months |

| 2 |

50, M Rajasthan (working in Tamilnadu for 20 y) |

Disseminated Nodulo-ulcerative lesion near the root of left middle finger extending into web space & right malleolus, 6 months |

Normal epidermis. Dermis showed ill-formed granulomas interspersed with abundant plasma cells. No LDB |

Positive | Positive | L. tropica | Anti-tubercular treatment for over a year | 30 i.v. injections of SAG 8ml (800mg), discontinued after partial regression due to deranged kidney function test; cryotherapy given for resolution | No recurrence after 1year follow-up |

| 3 |

22, M Uttarakhand |

Disseminated; Plaque left cheek Crateriform nodule on left arm, 2 months |

Dermis showed ill-formed granulomas. Dense pan-dermal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate extending into subcutis. No LDB |

Negative | Positive | L. tropica | Antibiotics |

LAmB i.v. 3 doses Lesions subsided in 9 months. |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 4 |

32, M Haryana |

Localised; Crusted plaque on left infra orbital area, cheek and groove of the nose, 6 months |

Epidermis- hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis. Dermis- dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells. No LDB |

Negative | Positive | ND |

Anti-tubercular therapy Itraconazole for sporotricho-sis |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Healed in 9 months. |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 5 |

25, M Uttarakhand |

Localised; Coin-sized plaque on the forehead with a central crater, 8 months |

Hyperkeratotic & acanthotic epidermis. Pandermal poorly formed granulomas; dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a moderate number of plasma cells. No LDB |

Negative | Positive | L. tropica | Antitubercular therapy | Did not complete treatment with LAmB | Not applicable |

| 6 |

45, F Rajasthan |

Localised; Erythematous induration left lower eye, 4months |

Acanthotic epidermis. Ill-defined epithelioid cell granulomas with a few giant cells, dense dermal infiltrate rich in plasma cells and histiocytes, Singly scattered LDB | Positive | Positive | ND | Lesion recurred after surgical excision elsewhere | Did not report for Treatment | Not applicable |

| 7 |

41, F Uttar Pradesh |

Localised; Plaque with a small central scab on the right cheek, 1 year |

Epidermis- acanthosis. Dermis- dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and histiocytes. No LDB |

Negative | Negative | L. tropica |

Anti-leprosy therapy Later misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided after 9 months |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 8 |

70, F Rajasthan |

Disseminated; Crateriform centrally crusted plaque on the forehead and left inner forearm since 6 months. |

Epidermis- atrophied with parakeratosis. Dermis-diffuse pan-dermal sheet-like infiltrate of histiocytes & plasma cells. LDB positive. | Positive | Negative | L. tropica | Nil |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided after 9 months |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 9 |

60,F Rajasthan |

Disseminated; Nodulo-ulcerative lesions over the forehead, both upper limbs & near the umbilicus, 8 months |

Epidermis- Hyperkeratosis focal parakeratosis, Dermis-aggregates of lymphohistiocytes and scattered plasma cells. No LDB | Positive | Positive | L. tropica | Anti-leprosy therapy with no relief |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Healed crusts were seen. |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 10 |

34, M, Delhi |

Disseminated; Large annular keratotic plaque on right calf, smaller on the left forearm and irregular plaques on left thigh & knee, 5 months |

Epidermis-Hyperkeratosis parakeratosis. Dermis- pan-dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate of lymphohistiocytes, plasma cells. No LDB |

Positive | Positive | L. tropica | Oral ketoconazole without any relief |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided after 10 months |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 11 |

6, M Nepal |

Localised; Crateriform crusted plaques on forehead & lower lip, 18 months |

Epidermis- Parakeratotic Dermis- chronic inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and a moderate number of plasma cells. No LDB |

Negative | Negative | L. tropica | Antibiotics |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided in 6months |

No recurrence after 6 months of follow-up |

| 12 |

60,F Delhi |

Localised; Erythematous plaque on the left cheek with central crust & a few satellite lesions, 4 years |

Dermis– Ill-defined epithelioid cell granulomas, pan-dermal dense plasma cells and histocytes No LDB. |

Positive | Positive | L. tropica |

Incised leaving scar; anti-tubercular therapy with no response |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided in 6months |

No recurrence after 1year follow-up. |

| 13 |

37, M Uttarakhand |

Localised; Plaque with central crust on the cheek, 6 months |

Epidermis- Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis. Dermis- dense infiltrates of lymphohistiocytesand scattered plasma cells, LDB seen. |

Positive | Positive | L. tropica | Anti-leprosy therapy, no relief |

LAmB i.v. 3 doses Lesions were reduced by 50% after the last injection. |

Lost to follow-up |

| 14 |

8, M Uttarakhand |

Localised; Erythematous nodule on the forehead, 6 years |

Epidermis- unremarkable Dermis-multiple poorly formed epithelioid cell granulomas with occasional giant cells lymphohistiocytes and plasma cells; No LDB. |

Negative | Positive | L. tropica | Nil |

LAmB i.v., 3 doses Lesions subsided, Complete healing in 6 months |

No recurrence after 1-year follow-up. |

| 15 |

41, M Himachal Pradesh |

Localised; Papulonodular lesion on the cheek, 4 months |

Epidermis- unremarkable. Dermis- circumscribed epithelioid cell granulomas, lymphohistiocytes, and scattered plasma cells. No LDB |

Negative | Positive | ND | Nil | Did not report for Treatment | Not applicable |

| 16 |

70,M Rajasthan |

Localised; Plaque over right. Cheek with scaling, 6 months |

Epidermis- parakeratotic. Dermis- diffuse sheets of plasma cells and histiocytes with LDB | Negative | Positive | ND | Nil | Did not report for Treatment | Not applicable |

M-male; F-female; LDB-Leishman-Donovan bodies; SAG-Sodium Antimony Gluconate; LAmB-Liposomal Amphotericin B; ND-not determined.

Ethical Approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Vardhaman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi (S. No. IEC/VMMC/SJH/Project/2021-10/CC-197).

Histopathology and slit smear microscopy

Punch biopsies were analysed by histopathology. Slit-skin aspirates were subjected to smear examination. Criteria for diagnosis were mainly based on the demonstration of LDB or characteristic features on histopathology showing a diffuse dermal infiltration of lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells.

Real time-PCR

QIAamp DNA Tissue kit (QIAGEN) was used to isolate DNA from slit aspirate/tissue samples. SYBR Green I-based Leishmania genus-specific Q-PCR based on k-DNA sequence was performed to detect the parasite as described earlier.20

CL Detect Rapid test

The CL Detect Rapid test (InBios International, USA) was performed with a slightly different approach from the dental broach method described in the kit manual and reported previously.7,10 Briefly, 2–3 drops of lysis buffer were added to a small volume of slit aspirate sample collected by skin scraping technique in a microcentrifuge tube and allowed to stand for 5–10 minutes. The test strip was placed into the sample from the loading position, and the results were interpreted after 15–20 minutes. A positive result was recorded when a control line and test line appeared in the test area, and a negative result when only the control line appeared.

ITS-1 PCR for species identification

ITS region was amplified with DNA isolated from confirmed CL cases, as described earlier.21 Sanger sequencing was done for the amplified product, and the reads thus obtained were analysed using NCBI- Basic Local Alignment Search Tool to identify the causative species.

Treatment and Clinical investigations

Treatment details were available for 12 of the 16 CL patients. After confirmation, the patients (n = 10) were given anti-leishmanial therapy with LAmB, 5 mg/kg, up to three doses, five days apart. The remaining two were treated with sodium antimony gluconate (SAG) 100 mg/ml, intralesionally in one case (200 mg, weekly, 3 times) and intravenously in the other (i.v. injections of SAG 800 mg, 30 days). Before treatment, baseline investigations were done, including a complete hemogram, liver and kidney function tests, and chest x-ray.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity and 95% confidence interval were determined using MedCalc statistical software (version 16.8.4).

Results

Demographic data and diagnostic tests

Of the 16 cases confirmed, 11 were males, and five were females. Fifteen cases hailed from Northern India (Rajasthan n = 6, Uttarakhand n = 4, Delhi n = 2, Haryana n = 1, Himachal Pradesh n = 1 and Uttar Pradesh n = 1) while one was from Nepal. The extent of CL observed was localised (n = 11) or disseminated (n = 5), as detailed in Table 1.

The onset of lesions at the reporting time varied from 2 months to 4 years. The lesions were erythematous nodules or raised plaques, with some showing thick central crusts. The most prevalent site was on the face in 14 cases. In the localised form, the eruptions were present on the face in all 11 patients; they were solitary in 7 and 2–3 in number in four. In the disseminated forms, either one or more of the extremities were affected; face was spared in 2 with many lesions in one patient being distributed on the right calf, and forearm and lower limb on the left side. In 13 of the 16 patients, the nodules had a sloping periphery and a central crater resembling a volcano. In some, the crust had fallen, revealing an erosion; in one case with disseminated lesions, the individual papules were flat or annular with central pits giving a honeycomb appearance. The other two had erythematous plaques with prominent irregular crust in one.

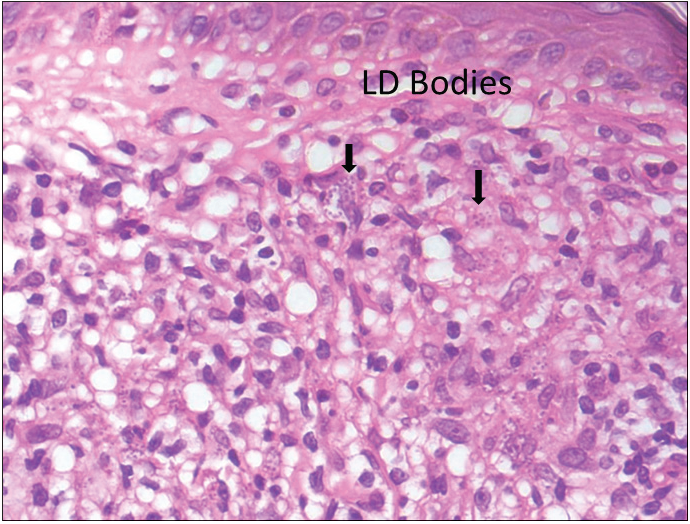

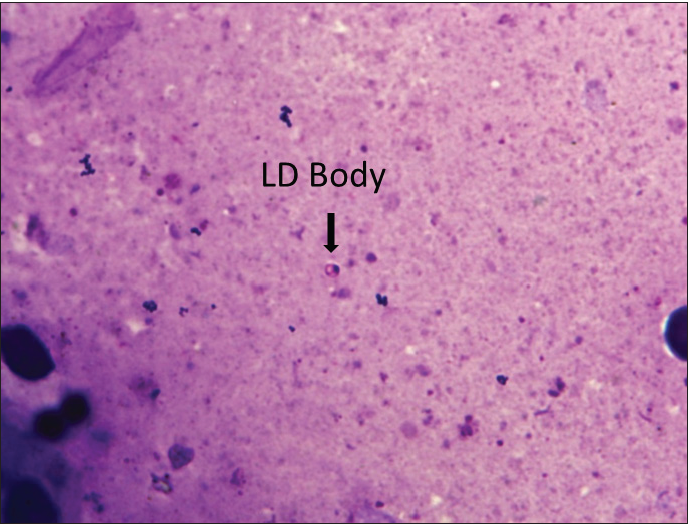

Histopathology showed normal to the atrophic epidermis with acanthosis in one case and parakeratosis in two cases. Dermis showed moderate to dense diffuse pan-dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes mixed with abundant plasma cells. Well- to ill-defined epithelioid cell granulomas were noted in 5 cases. Giemsa stain revealed LDB in 4/16 cases on histopathology and 7/16 slit-skin smears (sensitivity of 43.8%: 95% CI, 19.78–70.1%) [Figure 1].

- Dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate along with numerous LDB in the cytoplasm of histiocytes (H&E, 1000X).

- Slit skin smear showing a solitary LD body (H&E, 400X).

CL Detect Rapid Test performed in 16 confirmed CL cases were positive in 13 patients (81.3%; 95% CI, 54.4–96.0%). Although the assay is recommended for lesions not older than four months, it efficiently detected cases even when the lesions were older than four months. ITS-1 gene-based analysis identified L. tropica as the causative species in 12 samples.

Treatment

Intravenous infusion of LAmB was given in ten patients. After completion of three doses, the lesions showed 60% regression in 2–3 months, better appreciated in localised forms. Complete regression was seen in 6 months in three cases with localised CL [Figure 2]. The four disseminated and two localised forms took around 10 months for complete regression, while one case with localised CL, after taking all three doses, did not report for follow up. There was flattening of the nodules, a decrease in induration and re-epithelialisation of the ulcers. Complete re-epithelialisation was evident in the long-term follow-up [Figure 3]. Two patients were treated with SAG. One patient with a nodule on the upper lip responded to three intralesional injections of SAG. Another patient with disseminated CL, intolerant to LAmB, was given 8 ml (800 mg) SAG intravenously daily for 30 days.

- Localised cutaneous leishmaniasis – Pre-treatment.

- Localised cutaneous leishmaniasis – One month post-treatment (with LAmB).

- Localised cutaneous leishmaniasis – 10 months post-treatment complete re-epithelialisation.

- Disseminated Cutaneous Leishmaniasis – Pre-treatment.

- Disseminated Cutaneous Leishmaniasis – One month post-treatment (with LAmB).

- Disseminated Cutaneous Leishmaniasis – 3 years post-treatment complete re-epithelialisation.

Discussion

CL occurs mainly in resource-limited areas, and this study presents the cases that went undiagnosed during the initial visit of patients to doctors in endemic areas, mainly from parts of Rajasthan and Uttarakhand.

In expert hands, the positivity of LDB in slit-skin smears, better demonstrable in early lesions, is around 60%.2,4,22 The plausible reason for the observed low positivity (44%) rate seen here is that many of the patients have taken antibiotics known to be leishmanicidal, e.g. rifampicin. Our observations are similar to the histomorphologic pattern in LDB-negative patients, where a high plasma cell density distributed diffusely and ill-formed granulomas should alert one to the possibility of CL.23

The distinctive feature is the volcano sign seen in the lesions of most of our patients, in which the often elevated lesions show a central crater or crust mimicking a volcano.24 It was also seen that the lesions evolved as groups of papules and characteristically revealed central pits resembling mini craters.25 These features should raise the suspicion of CL in non-endemic areas since these are less common in other infective granulomas like tuberculosis and leprosy.4,26

CL Detect Rapid test is an easily accessible tool, requiring little expertise in handling when performed with slit aspirate for sample collection. We observed the sensitivity of the CL Detect Rapid test to be 81.3%, higher than that reported in previous studies, possibly because slit aspirates from only confirmed cases of CL were subjected to the test.7,10

The availability of antimonials is a problem, and alternative drugs like dapsone, rifampicin, and azoles are not consistent in their efficacy.27 Further, some patients in our series had already taken these drugs. Hence LAmB, which had proven effective in both old and new-world CL, was evaluated and found to be highly effective.

Limitations

In this retrospective analysis, a small number of patients were analysed, and results on the performance of a CL Detect Rapid Test only on confirmed cases of CL and a short treatment with LAmB are presented.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the application of the CL Detect Rapid test as a point-of-care test and also established the excellent performance of LAmB for treating CL.

Acknowledgement

The CL detect Rapid test kit was provided by InBios International, USA.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study, in part, was supported by ICMR grant no. 6/9-7(228)2020-ECDII.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis, updated-8 January 2022. Accessed-6 November 2022.

- Localised cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani and Leishmania tropica: preliminary findings of the study of 161 new cases from a new endemic focus in Himachal Pradesh, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:819-24.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an emerging infection in a non-endemic area and a brief update. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:272-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and epidemiological study of cutaneous leishmaniasis in two tertiary care hospitals of Jammu and Kashmir: An emerging disease in North India. Int J Inf Dis. 2021;103:138-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical spectrum of cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview from Pakistan. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012;18:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sri Lankan cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania donovani zymodeme MON-37. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:380-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of a rapid diagnostic test based on antigen detection for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in patients with suggestive skin lesions in Morocco. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:716-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of serological and parasitological methods for cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosis in the state of Paraná, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13:47-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of point of care tests for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Suriname. BMC Inf Dis. 2019;19:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of point-of-care tests for cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosis in Kabul, Afghanistan. EBioMedicine. 2018;37:453-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The applicability of real-time PCR in the diagnostic of cutaneous leishmaniasis and parasite quantification for clinical management: current status and perspectives. Acta Trop. 2018;184:29-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heat-shock protein 70 gene sequencing for Leishmania species typing in European tropical infectious disease clinics. Eurosurveill. 2013;18:20543.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leishmania donovani complex: Genotyping with the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and the mini-exon. Parasitology. 2004;128:263-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-60.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynamics of parasite clearance in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients treated with miltefosine. PLoS Neg Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1436.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of topical liposomal amphotericin B versus intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Parasitol Res 2011:2011-656523.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liposomal amphotericin B in travelers with cutaneous and muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis: not a panacea. PLoS Neg Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006094.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomised controlled trial of local heat therapy versus intravenous sodium stibogluconate for the treatment of cutaneous Leishmania major infection. PLoS Neg Trop Dis. 2010;4:e628.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of thermotherapy to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in Kabul, Afghanistan: a randomised, controlled trial. Clin Inf Dis. 2005;40:1148-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of parasite load in clinical samples of leishmaniasis patients: IL-10 level correlates with parasite load in visceral leishmaniasis. PloS One. 2010;5:e10107.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in Bikaner, India: parasite identification and characterisation using molecular and immunologic tools. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:896-901.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correlation of clinical, histopathological, and microbiological findings in 60 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:28-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of histopathology in the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A Case–Control Study in Sri Lanka. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:566-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. The leishmaniases in biology and medicine. Volume II. Clinical aspects and control 1987:617-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unusual presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:55-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:23-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis with dapsone, itraconazole, cryotherapy, and imiquimod, alone and in combination. Intl J Dermatol. 2009;48:862-9.

- [Google Scholar]