Translate this page into:

Comparison of self-estimated and clinician-measured SALT score in patients with alopecia areata: Patients with alopecia areata perceive themselves as more severe than dermatologists

Corresponding author: Won-Soo Lee, Department of Dermatology, Wonju Severance Christian hospital, Ilsan-ro 20, Wonju, Korea. leewonsoo@yonsei.ac.kr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Lee JY, Lee JW, Lee WS. Comparison of self-estimated and clinician-measured SALT score in patients with alopecia areata: Patients with alopecia areata perceive themselves as more severe than dermatologists. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:235–7. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_439_2022

Dear Editor,

Alopecia areata (AA) has a global prevalence of 2% and causes non-scarring hair loss due to autoimmunity.1 Hair loss in AA affects the patient’s quality of life (QoL) and causes psychosocial problems. In addition, several studies have found that psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities significantly worsen in patients with AA, and they perceive themselves more severely than dermatologists.2–4 Based on these studies, we attempted to determine whether patients with AA in our hospital also evaluated themselves more severely and whether this had a more significant effect on QoL.

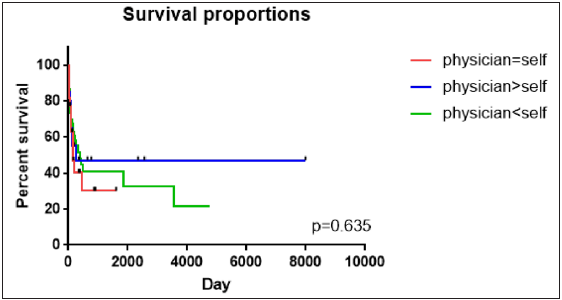

This study was conducted retrospectively on patients who visited Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital from April 2019 to May 2021. In our clinic, we routinely administer a questionnaire measuring the Hair Specific Skin Scale-29 (HSS-29), which consists of three domains (function, symptoms and emotions) and a self-estimation of alopecia severity tool (SALT) score to all patients with AA [Figure 1].5,6 We reviewed the patient’s medical records and questionnaires and measured the initial SALT score using photographs from the first visit. We excluded patients under the age of 11 years because we thought it would be difficult for them to self-estimate their SALT score. We also excluded patients who did not complete the HSS-29 questionnaire at the first visit, did not have a clinical photograph at the first visit, or the photograph was inappropriate for the estimation of the SALT score. We divided patients with AA into three groups to see how they estimated their severity: ‘self-estimated SALT score < clinician-measured SALT score’, ‘self-estimated SALT score = clinician-measured SALT score’, and ‘self-estimated SALT score > clinician-measured SALT score’. The initial SALT score was compared to assess QoL in each group. We also evaluated the duration of follow-up to assess compliance in these patients and only included patients with three or more visits to AA to avoid misclassification. ANOVA was used to analyse differences in HSS-29 and SALT scores between groups, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to determine compliance. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS 28.0 (IBM, New York, United States) and R 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (CR321151). A waiver of informed consent was granted owing to the deidentified data used.

- A self-administered questionnaire for evaluating the SALT score. (SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool).

A total of 114 patients with AA were included, and 70 patients (61.4%) were in the group with a high self-estimated SALT score. Functioning (p < 0.001), symptoms (p = 0.026), emotions (p = 0.005) and total HSS-29 scores (p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the group with a higher self-estimated SALT score than in the other groups. In addition, their self-estimated and clinician-measured SALT score (p < 0.001 and p = 0.029, respectively) were significantly higher than in the other groups [Table 1]. There were no significant differences in compliance [Figure 2].

| SALT score | Clinician>Self | Clinician=Self | Clinician<Self | P* value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 23 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 70 (100%) | ||

| Age | 43.7 ± 18.7 | 48.8 ± 16.7 | 40.8 ± 13.4 | 0.108 | |

| Sex | Male | 12 (52.2%) | 7 (33.3%) | 40 (57.1%) | 0.200 |

| Female | 11 (27.8%) | 14 (66.6%) | 30 (23.9%) | 0.819 | |

| Total HSS-29 score ± SD | 35.6 ± 22.3 | 48.2 ± 30.9 | 48.2 ± 30.9 | 0.001 | |

| Functioning scale score ± SD | 8.0 ± 6.7 | 12.5 ± 8.4 | 18.0 ± 11.6 | 0.026 | |

| Symptoms scale score ± SD | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 6.8 ± 4.3 | 8.5 ± 4.0 | 0.005 | |

| Emotion scale score ± SD | 13.6 ± 7.1 | 15.6 ± 9.6 | 21.0 ± 10.3 | 0.001 | |

| Self-SALT score | 15.3 ± 14.6 | 9.6 ± 6.9 | 26.8 ± 22.9 | 0.001 | |

| Clinician SALT score | 17.3 ± 15.6 | 9.6 ± 6.9 | 21.7 ± 21.0 | 0.029 | |

- Kaplan–Meier plot of the loss-to-follow-up rate by group. The loss-to-follow-up of the three groups was compared. p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Abbreviations: SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool.

In our study, most patients with AA had a worse perception of their condition than they actually did and had significantly higher HSS-29 scores than those who did not. In addition, the SALT score was higher in the group who perceived themselves as worse. Previous meta-analyses have shown poorer QoL and mental health in patients with AA.4 Our results were consistent with the previous study. Patients with AA might perceive themselves as more severe, leading to a poorer quality of life and mental health. As these patients scored higher on symptoms, functioning and emotions, they might have more psychosocial and psychiatric problems. In our previous study of patients with androgenetic alopecia (AGA), higher HSS-29 scores were associated with poorer compliance.7 So, in this study, patients who overestimated themselves tended to have higher HSS-29 scores, so we expected to see poorer compliance in these patients, but this was not the case. We considered that this might be because some patients with AA, unlike AGA, are self-limiting or show dramatic improvement.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective, single-centre study. Second, our study did not analyse hair loss in areas such as eyebrows and body hair. Nevertheless, the strength of our study was that patients estimated themselves and the differences were analysed with clinicians.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware that some patients with AA tend to perceive their symptoms as more severe than they actually are, which can affect their quality of life.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The Alopecia Areata Investigator Global Assessment scale: A measure for evaluating clinically meaningful success in clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:702-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Alopecia areata and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:561-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life assessment in male patients with androgenetic alopecia: Result of a prospective, multicenter study. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:311-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALT II: A new take on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) for determining percentage scalp hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1268-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low quality of life and high HSS-29 scores reflect the risk of loss to follow-up: A study in patients with androgenetic alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e457-e9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]