Translate this page into:

Delving into the depth: On the historical aspect of ingrown toenails from the ancient period till the 19th century

Corresponding author: Dr. Amiya Kumar Mukhopadhyay, Consultant dermatologist, ‘Pranab Skin Clinic’, Pranab Ismile (Near Dharmaraj Mandir), Asansol, West Bengal, India. amiya64@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mukhopadhyay AK. Delving into the depth: On the historical aspect of ingrown toenails from the ancient period till the 19th century. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:408-15. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1034_2023

...the evolution of bipedal locomotion seems to have preceded other uniquely human attributes. It appears quite probable that our ancestors walked first, and subsequently became large-brained, tool-using humans.

Mednick LW (1955).1

Introduction

The erect posture and subsequent bipedal locomotion are considered the first and singular most important factor in the hominid evolution. With bipedalism, humans gained a distinct advantage over most other animals. To avail this evolutionary benefit the feet became flat and the great toes were predominantly modified.2,3 The immense role of the great toe in erect posture and bipedal walking has puzzled and attracted attention of the scholars working on the kinetics and kinematics of bipedal walking. The hallucal distal phalanx of humans is both laterally angled in the transverse plane and medially torqued along the long axis of the bone and helps in bipedal propulsion. The centre of gravity passes through the ball of the great toe and in the final stage of forward propulsion while walking, the body weight is transferred to the ball of the foot with peak pressure under the medial metatarsal and ultimately ending with toe-off pressure.4,5 But as every good thing comes with a price, so also do the advantages of big toes. Various diseases of the big toes, namely ingrown toenails, corns, and callosities have rendered trouble and posed profound challenges to mankind. Consequently, men tried to find the reason and remedy since the early days which was evident in the medical texts since ancient times. As footwear has been held as one of the common contributory factors, the description of ingrown toenails is more prevalent in the medical literature of foot-wear using civilisations. Controversies surrounded this entity including its cause and treatment since the ancient period. These debates settled with the description of Durlacher.6

Etymology

Since the early days, ingrown toenails have been described under the different names of paronychia, onychia, whitlow, etc. With time, it had been variously termed as ingrowing or ingrown toenails, infleshed toenails, embedded toenails, onychocryptosis, onyxis, ongle incarné, unguis incarnatus, etc. Greeks called it pterúgion (Pterύgion) and in Latin it was reduvia or excrescentia unguis fungosa.7 It has been argued that when the nail is primarily at fault, the condition should be termed as an ingrown or ingrowing toenail, whereas with problems in the lateral nail folds, it is onychocryptosis.8 Different types of this ailment have been described.9

On the disease and its aetiology: from the pages of history

In the history of medicine, Egyptian papyri are considered the oldest written records discovered to date. The Hearst papyrus of the first half of the second millennium BCE contained discussions on the ailments of fingers and toes in plate numbers XI to XIII. The subjects on pages XII (lines 6, 7, 11, 13, and, 15) and XIII (lines 3 and 6) specifically discussed the diseases of fingers and toenails. Out of these prescriptions, plate number XII, line 11, and plate number XIII, line 7 mentioned an open sore around the toenail and swelling of the toes, respectively. Whether it included ingrown toenails was difficult to ascertain.10,11 The Ebers papyrus (c.1550 BCE) also discussed nail diseases but did not mention ingrown toenails.12

In the ancient Ayurvedic literature of India, a description suggestive of this disease (Chippam) and its medical and surgical management have been mentioned. It was also designated as Upanakha and Kshataroga and placed under a group of smaller diseases (Kshudraroga).13,14 Sushruta Samhita (c.6th century BCE) remarks that the deranged humour of vayu and pitta vitiating the flesh of the fingernails gives rise to a disease that is characterised by pain, burning, and suppuration.15 A similar condition (charmanakhashotha) arising between the nail and the flesh that may be suggestive of this ailment can be found in Charak Samhita of the first-millennium BCE.16,17 Madhavanidana (c.7th century CE), a book of diagnostics, mentioned this sickness like its predecessors.18

Votive offerings of ingrown toenails were presented in ancient Italy during the 4th to 1st century BCE.19,20 Celsus (c. 25 BCE–c. 50 CE) in his De Medicina described a disease around the nails that contained some condition (caruncle) like ingrowing toenails though he described it under the heading: Of the ulcers in the fingers. Celsus mentioned that the Greeks called it pterygion.21 Oribasius (320–400 CE), a Greek medical writer and personal physician of the Roman emperor Julian, wrote about it.22 Paulus Aeginita (c.625–c.690) also described the condition of fungous flesh covering part of the nail as pterygium caused by whitlow or some identical condition. Ingrown toenail has been described by eminent authorities of the Islamic world like Rhazes (c. 864/865–c.925/935), Haly Abbas (930–994), Albucasis (936–1013), Avicenna (980–1037) and others.23,24 The ancient foot--binding practice originated in 10th century China and was a painful exercise that sometimes led to onychocryptosis.25

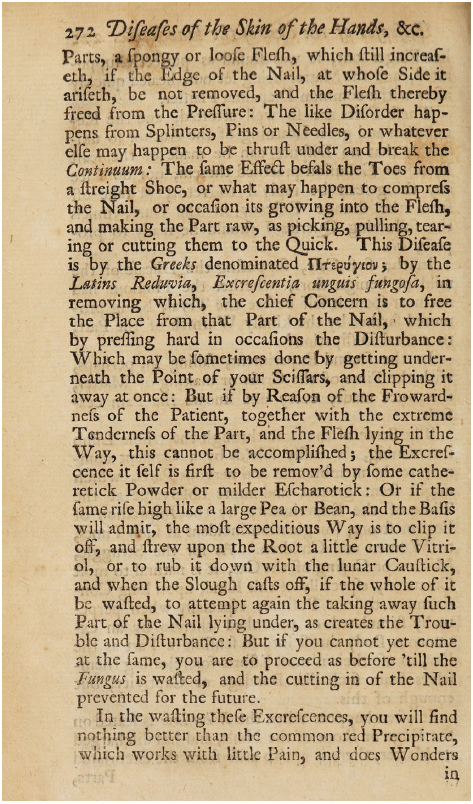

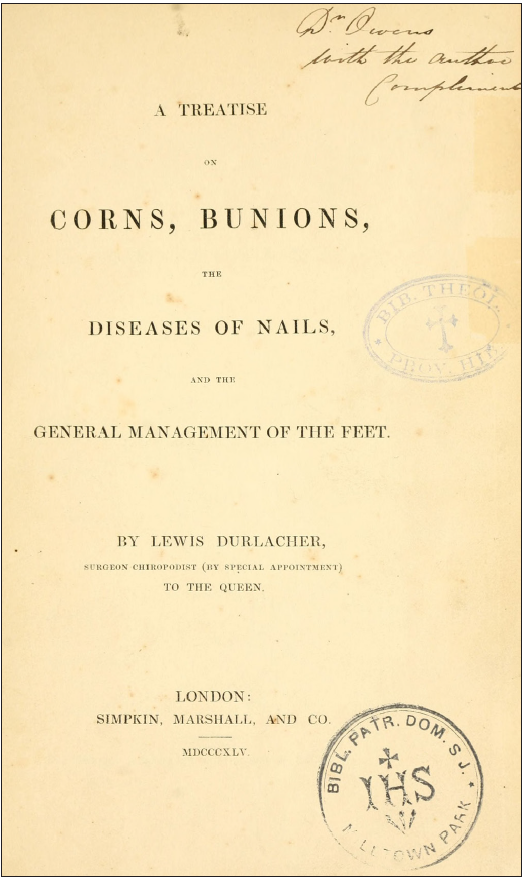

The eminent British physician Daniel Turner (1667–1741) in his De morbis cutaneis (1723), the first book of skin diseases in the English vernacular, described the condition and held the ill-fitting shoes responsibly - [Figures 1a, and 1b].7 Rousselot, a French surgeon, wrote about this ailment in Toilette des pieds (1769) – a treatise considered to be the first book on chiropody [Figures 2a, and 2b].26 After the death of Rousselot, these notes were relocated to Nicholas Laurent La Forest, a practicing Chirurgien-pédicure, to Louis XVI. He began the scientific writing on chiropody in his L’art de Soigner Les Pieds (1781) and explained the cause of onychocryptosis.27 Plenck (1735–1807) in Doctrina de morbis cutaneis (1783) mentioned it as pterygium unguis in the chapter of Morbi unguium.28 At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the chiropodist Heymann Lion portrayed a detailed account in his Spinae pedum (1802). He blamed faulty paring of nails with rounding of the corners.29 Wardrop (1814) also provided a comprehensive explanation of the subject in his surgical discourse.30 Durlacher in later years acknowledged Wardrop’s view. Rayer, a distinguished dermatologist of the early nineteenth century, maintained that the affliction was caused by mechanical irritation secondary to accidental trauma, the defective configuration of the nail, irregular growth or great convexity of the nail, and pressure of the tight shoes.31 The eminent dermatologists of the nineteenth century like Erasmus Wilson, Tilbury Fox, Duhring, and others also held similar views.32,33,34 From the ancient days of medical history till the nineteenth century, several works provided exhaustive descriptions of the cause and clinical picture of this condition but in 1845 Durlacher was probably the pioneer in mentioning and emphasising the inappropriate cutting of the nail as the reason behind this ailment.35 He gave a clear and complete picture of the condition describing it as the ‘nail growing into the flesh’ in his treatise A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails and the general management of the feet (1845) [Figures 3a and 3b].6 Notably, this book also contained the first illustration of an ingrown toenail [Figure 4].6 Dagnall in his landmark paper on the history of chiropody literature placed this book as the most important one that ‘placed chiropody on a scientific basis’.36 In 1869, Emmert, a Bernese surgeon proposed the three stages of ingrowing toenails for the first time.37

- The title page of Daniel Turner’s De morbis cutaneis (1723). (Credit: De morbis cutaneis. A treatise of diseases incident to the skin with an appendix concerning the efficacy of local remedies by Daniel Turner. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

- On the management of ingrown toenails in Turner’s De morbis cutaneis (1723). (Credit: De morbis cutaneis. A treatise of diseases incident to the skin with an appendix concerning the efficacy of local remedies by Daniel Turner. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

![Title page of the first book on Chiropody by Rousselet (1769). (Credit:Toilette des pieds, ou traité de la guerison des cors, verrues, et autres maladies de la peau: et dissertation abrégée sur le traitement et la guérison des cancers/[Rousselot]. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).](/content/126/2024/90/3/img/IJDVL-90-3-408-g3.png)

- Title page of the first book on Chiropody by Rousselet (1769). (Credit:Toilette des pieds, ou traité de la guerison des cors, verrues, et autres maladies de la peau: et dissertation abrégée sur le traitement et la guérison des cancers/[Rousselot]. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

![The page from Rousselot’s treatise (1769) on the management of ingrown toenails. (Credit:Toilette des pieds, ou traité de la guerison des cors, verrues, et autres maladies de la peau: et dissertation abrégée sur le traitement et la guérison des cancers/[Rousselot]. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).](/content/126/2024/90/3/img/IJDVL-90-3-408-g4.png)

- The page from Rousselot’s treatise (1769) on the management of ingrown toenails. (Credit:Toilette des pieds, ou traité de la guerison des cors, verrues, et autres maladies de la peau: et dissertation abrégée sur le traitement et la guérison des cancers/[Rousselot]. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

- The title page of A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails: and the general management of the Feet (1845) by Lewis Durlacher. (Credit: A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails: and the general management of the feet by Lewis Durlacher. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

- The page from Durlacher’s book mentions the nail growing into the flesh (1845). (Credit: A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails: and the general management of the feet by Lewis Durlacher. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

- The first-ever illustration of an ingrown toenail in Durlacher’s treatise (1845). (Credit: A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails: and the general management of the feet by Lewis Durlacher. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark 1.0).

Nail into the flesh or flesh onto the nail

Several arguments have been put forward and a lot of causative factors have been enumerated regarding the aetiopathogenesis of ingrowing toenails.8,9,38 Heifetz argued that ingrown toenail is a misnomer and wrote: It is generally conceded that the underlying pathology is not the growth of the nail into the flesh, but rather the growth of the flesh upon the edge of the nail.39

Historically, the earliest explanation was proposed in the ancient Indian texts of Ayurveda as the vitiation of the humours vata (air) and pittam (bile) as the reason for ingrown toenails. Paulus Aegineta commented that it was commonly caused by accident. Turner opined that any trauma from splinters, pins, or needles was the reason and blamed shoes that might compress the nail leading to the malady. Plenck maintained that prolongation and increase of the epidermis at the root of the nail was the cause. Though Durlacher is credited with his argument of ‘nail growing into the flesh’, Wardrop in an article commented about the ‘growth of the nail into the flesh’ in 1814.30

Treatment: A Look Back

Since the early days of human history, various remedies have been tried to mitigate the misery of painful ingrown toenails. The several avenues available today to manage it are the outcomes of the endeavour of innumerable known and unknown medical persons.9,39

The ancient Egyptian papyri like the Hearst papyrus mentioned many finger and toe conditions that might have included this ailment too, albeit not very clearly. There are about 36 remedies and one of them is to ‘remove the swelling of the toe’.10,11 The ancient Indian Ayurvedic text Sushruta Samhita (c. 6th century BC) said that the affected part should first be washed with hot water, drained with a knife, and subsequently anointed with medicated oil. Resin powder should be sprinkled over it and bandaged. If this failed, thermocautery used to be done.15 Similar therapies echoed in other Ayurvedic texts like Astanga Hridayam (6th century CE), Sharangdhara Samhita (12th century CE), Bhavaprakash (16th century CE), etc. Chakradatta, an 11th-century treatise, has advised fomentation instead of washing with hot water which is in contrast with Sushruta’s advice.40

As footwear is an important factor, the quest for remedies for ingrowing toenails is more ubiquitous in the medical literature of shoe-wearing civilizations. Celsus suggested a mixture made of alum and honey to be rubbed on the lesion for extirpation. If it does not work, it should be fomented and a medicine composed of calcite, pomegranate bark, copper scales, honey, etc., should be applied and wrapped with moistened linen. In case it failed, surgery using a knife was the final way to alleviate the ailment.21 Oribasius prescribed various mixtures composed of crushed incense, iron, realgar, etc. Another combination he prescribed was a compound containing honey, gallnuts, sour pomegranate peel, red copper, and burnt dried fig compounded to form a liniment and applied under a bandage twice daily.22 Paulus Aegineta advised a formula of arsenic and manna covered with a plug or roll of lint containing wine and sponge. Along with this, he also suggested the administration of medicines and methods as previously described by Celsus and Oribasius. Paulus also suggested raising and cutting the corners of the nails with a scalpel. Various famous authorities like Rhazes, Haly Abbas, Albucasis, and Avicenna of the Islamic medical world also described in detail the management of medicines as well as surgery using lancets and cautery.23,24 Ambrose Paré (1510–1590) treated this condition by pushing a straight-edged bistoury through the base of the soft parts covering the nail and removing these with subsequent cauterisation with the red-hot iron.31 Fabrizius ab Aquapendente (1537–1619) advised excision and avulsion of the ingrowing nail margin.9 Turner suggested the introduction of the point of the scissors underneath the affected area of the nail and clip it at the earliest, but if the excrescence was very painful then cathertick powder or escherotick or crude vitriol and lunar caustic is used to expedite the sloughing of the growth and then the affected nail is removed.7 La Forest echoed the views of Turner.27 Plenck in his Doctrina de morbis cutaneis remarked that the epidermis be separated from the nail with a knife as treatment.28 Lion opposed the then-prevalent practice of scrapping the nail. He described the operation for the ingrowing toenail exhaustively in his treatise.29 Wardrop discussed the management with lunar caustic and suggested the old but prevalent method of cutting a V-shaped notch in the upper surface of the nail.30 Michaelis (1830) described various treatment procedures.41 Gosselin described the removal of an elliptical wedge-shaped piece of nail matrix and skin including the whole nail groove along the edge.42 Durlacher, the most prominent chiropodist of his time in England, reviewed the ancient and prevalent methods of management of the condition and advocated his way of treatment of dividing the affected nail longitudinally to relieve the sulcus pressure.36 Hildebrandt (1884), Quenu (1887), Anger (1899), and others added further to the subject. Quenu’s radical nail bed and matrix ablation method was popularised in the 20th century as Zadik’s procedure.9 Foote in 1899 compared different methods of operation for ingrowing nails and for the first time described selective matrix horn resection.43

Most of the time the treatment was more painful and even fatal than the disease itself, so much so that at times it had to witness a tragic end.44 This can be visualised from the description of Dupuytren in article VIII entitled D’longle rentré dans les chairs (Of the nail tucked into the flesh) of his book Leçons orales de clinique chirurgicale where he wrote:45

¼the moment of the operation being judged suitable, I engage the tip of a branch of straight, solid well-sharpened scissors under the middle of the nail. I drag them by a rapid movement to the root and divide the nail by one cut into two roughly equal halves; then seize the half corresponding to the ulceration with dissecting forceps and tear it off by rolling it over inside out. If the other side is bad, I remove it in the same way. In case the fungous flesh surrounding the wound is too high I pass over a hot cautery which consumes them and thus assures, as much as possible, the cure of the disease.

Considering the prevailing situation of agonising management of the condition, one of the most important developments is the use of anaesthesia which ended the anguish of patients and helped surgeons to perform their job better to yield a more fruitful outcome. It was probably in 1853, Robert Liston (1794–1847) the British surgeon famous for his skill and swiftness in surgery during the pre-anaesthetic era first used anaesthesia for the operation of an ingrown toenail ‘removed, by revulsion (avulsion), both sides of the great toenail’.46

Many dermatologists, surgeons, and chiropodists worked and detailed the management of the ingrowing toenails during and after Durlacher, but they followed the existing ones without much new contribution during the 19th century. Many newer methods were developed thereafter, but there is no unanimous way to relieve the agony of the sufferers yet and debate is continuing about the best way to treat this condition.

The history of ingrowing toenails is fascinating. Since the early days of medical history, this painful condition has been mentioned. Men tried to find out its reason and remedy and all possible avenues were ventured – from poultice of bread to paring of nails, from lateral matricectomy to most advanced laser surgery but it had remained a tough problem to treat. About 170 years back, Gosselin enumerated about 75 types of local management.47

The history of the ingrown toenail witnessed various landmark events and the seeds of major developments germinated during the 19th century. A summary of these significant events is given in Table 1. We have traversed a long way since the ancient period to reach the modern scientific remedy for this ailment and various strategies have developed. Table 2 summarises these different treatment options and the landmark progress with the period of these procedures is presented in Table 3.8,9,48–51 The advent of anaesthesia has led to the tragic picture of agonising pain inflicted by the pointed blade of sharp scissors, a common scenario in the operating room, to the pages of the book of the history of medicine. With the rapid advancement in medical science and technology, days are not far away when there will be no more long-lasting morbidity and permanently distorted toes and nails and the tale of the painful ingrown toenail will become a story of the past.

| Authorities | Period | Important events |

|---|---|---|

| Hearst papyrus11 | First half of the second millennium BCE | Mentions open sore around the toenail and swelling of the toes (probable ingrown toenail). |

| Sushruta Samhita15 | 6th century BCE | Mentions chippam – an entity suggestive of ingrown toenails. Prescribed anointment and thermocautery. |

| Charak Samhita16 | First-millennium BCE | Described charmanakhashotha – an entity suggestive of ingrown toenails. |

| Celsus21 | c. 25 BCE–c. 50 CE | Suggested a mixture of alum and honey for extirpation and surgery, if needed. |

| Ambrose Paré31 | 1510–1590 | Used bistoury and red hot iron. |

| Fabrizius ab Aquapendente9 | 1537–1619 | Advised excision and avulsion of the ingrowing nail margin |

| Daniel Turner7 | 1667–1741 | Held ill-fitting shoes as the responsible factor. Suggested use of scissors and escharotics. |

| Nicholas Laurent La Forest27 | 1781 | Tried to explain the cause of onychocryptosis scientifically. |

| Heymann Lion29 | 1802 | Blamed faulty paring of nails and ill-fitting shoes. |

| Wardrop30 | 1804 | Use of lunar caustics and supported the cutting of a V-shaped notch. |

| Lewis Durlacher6 | 1845 | Gave a clear and complete picture of the condition describing it as the ‘nail growing into the flesh’ in his treatise. |

| Robert Liston46 | 1853 | First anaesthesia for ingrown toenail operation. |

| Emmert37 | 1869 | Proposed three stages of ingrowing toenails. |

| Quenu9 | 1887 | Advocated radical nail bed and matrix ablation. |

| Foote43 | 1899 | First described selective matrix horn resection. |

| Method | Techniques |

|---|---|

| Conservative treatment |

Compression and massage Taping Packing False nail Use of dental floss Gutter treatment Unbending of nails using braces Nail tube splinting (sleeve technique) Use of superelastic wire Nail ironing |

| Narrowing the nail plate permanently |

Narrowing the nail plate permanently Chemical cauterisation (phenol, sodium hydroxide, trichloroacetic acid) Wedge excision (Winograd’s, Zadik’s, or Emmert’s procedures, etc.) Laser therapy (e.g., CO2 laser) Electrocautery Radiosurgery Curettage of lateral horns |

| Reduction of the periungual soft tissue |

Howard–Dubois procedure Vandenbos’ procedure Super U procedure Noël’s procedure Tweedie and Ranger’s transposition flap Terminal Syme operation Avulsion Deroofing |

| Period | Important events |

|---|---|

| 1929 | Winogard described wedge resection of the toenail and nail fold.8 |

| 1945 | Otto Boll told about the chemical partial matricectomy using phenol.52 |

| 1950 | Zadik advocated radical nail bed and matrix ablation.9 |

| 1959 | Vandenbos and Bower described the soft-tissue nail fold excision technique8 |

| 1959 | DuVries used wide excision of the lateral nail wall and subcutaneous fat.9 |

| 1974 | Howard and Dubois’s method is about removing a crescent of soft tissue from the tip of the toe.48 |

| 1975 | Wallace described the gutter treatment.9 |

| 1983 | A carbon dioxide laser was used.8 |

| 1985 | Tweedie and Ranger’s transposition flap method is described.8 |

| 1989 | Ival Peres Rosa described the super U procedure.8 |

| 2008 | Noël’s procedure advocates the reduction and removal of the lateral nail fold.48 |

| 2009 | The use of trichloroacetic acid was reported.9 |

Acknowledgement

The author would like to express his gratitude to Prof. Vincent J. Hetherington, DPM, MS, Emeritus Professor, College of Podiatric Medicine, Kent University, Ohio, USA for the critical review and suggestions during the preparation of this article and for providing various instrumental literature on the subject.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Food transport and the origin of hominid bipedalism. Am Anthropol. 1961;63:687-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. New York: D Appleton and Co.; 1897. p. :51-3.

- A treatise on corns, bunions, the diseases of nails and the general management of the feet. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co.; 1845. p. :120-51.

- De Morbis Cutaneis. A treatise of diseases incident to the skin. London: R. Bonwicke, J. Walthoe, R. Wilkin, T. Ward, and S. Tooke.; 1723. p. :267-73.

- Nail surgery. In: Baran R, ed. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management (5th ed). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell.; 2019. p. :825-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The Old Egyptian Medical Papyri. Kansas: University of Kansas Press.; 1952. p. :54-94.

- The Hearst medical papyrus. Leipzig: J C Hinrichs.; 1905. p. :8-13.

- The papyrus Ebers. London: Geoffrey Bles.; 1930. p. :59.

- Etiopathological study of different kshudra rogas & its management. IJRMST. 2019;8:79-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Susruta Samhita. Vol Vol II. Calcutta: Published by the Author.; 1911. p. :88-451.

- The Charaka Samhita.Vol-V. Jamnagar: Shree Gulabkunverba Ayurvedic Society.; 1949. p. :641.

- Contribution of Ayurveda for management of Onychocryptosis (In growing Toe Nail) (Chippa): A Case Report. NJRAS [Internet]. 2022Oct.210(04). Available from: https://www.ayurlog.com/index.php/ayurlog/article/view /1058. [last accessed on 2023, Sep. 29].

- Madhavanidan. Gorakhpur: Geeta Press.; 1932. p. :523.

- Anatomical votive reliefs as evidence for specialization at healing sanctuaries in the ancient mediterranean world. Athens J Health. 2014;1:47-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mobility impairment in the sanctuaries of early Roman Italy. In: Laes C, ed. Disabilty in antiquity. London and New York: Routledge.; 2016. p. :248-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Of medicine (translated to English by Greive J). London: Wison D and Durham T.; 1756. p. :356-76.

- Oeuvres D’ Oribase. Paris. A L’imprimerie Nationale: J.-B. Baillière & fils.; 1873. p. :351-3.

- Seven books of Paulus Aegineta. Vol Vol-I, Book III. London: The Sydenham Society.; 1844. p. :679-80.

- Seven books of Paulus Aegineta. Vol Vol-II, Book VI. London: The Sydenham Society.; 1846. p. :414-5.

- Toilette des pieds, ou traité de la guerison des cors, verrues, et autres maladies de la peau: et dissertation abrégée sur le traitement et la guérison des cancers. Paris: Dufour.; 1769. p. :100-18.

- L’art De Soigner Les Pieds. Paris: Blaizot.; 1781. p. :84-112.

- Doctrina de morbis cutaneis. Vienna: R Graeffer.; 1783. p. :125.

- An entire, new, and original. work, being a complete treatise upon spinae pedum; containing several important discoveries. Edinburgh: H Inglis.; 1802. p. :284-385.

- An Account of some diseases of the toes and fingers; with observations on their treatment. Med Chir Trans. 1814;5:129-456.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A theoretical and practical treatise on the diseases of the skin. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart.; 1845. p. :383-5.

- On diseases of the skin. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea.; 1857. p. :613.

- Notes on the treatment of skin diseases. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.; 1877. p. :94.

- Practical treatise on diseases of the skin (2nd ed). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Co.; 1881. p. :397.

- Historic aspect of nail diseases. In: Scher RK, Daniel III CR, eds. Nails: Diagnosis, therapy, surgery (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005. p. :7-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zur Operation des eingewachsenen Nagels. Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 1869;11:266-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A review of management of ingrown toenails and onychogryphosis. Can Fam Physician. 1988;34:2675-81.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Chakradatta.4th ed. Clacutta: Ashubodh vidyabhusan and nityabodh vidyaratna; 1914. p. :540.

- Ongle incarné et son traitement. Clinique chirurgicale de l’hopital de la Charité. Tome Premier. Paris: Librairie J-B. Baillière Et Fils; 1879. p. :111-25.

- Leçons orales de clinique chirurgicale de Dupuytren.Vol-IV. Paris: Germer Baillière.; 1839. p. :392.

- Statement, supported by evidence of Wm. T.G. Morton, M.D., on his claim to the discovery of the anæsthetic properties of ether, submitted to the honorable Select Committee appointed by the Senate of the United States 32nd Congress, 2nd session. Washington: United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee On Ether Discovery, and United States Congress.; 1853. p. :130.

- Ingrown toenail. In: Singal A, Neema S., Kumar P, eds. Nail disorders: A comprehensive approach. New York: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group.; 2019. p. :177-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ingrown toenails. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:279-89.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical matricectomy for ingrown toenails: Is there an evidence basis to guide therapy? J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:287-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]