Translate this page into:

Rituximab in the treatment of severe childhood pemphigus vulgaris accompanying phenylketonuria: A case report

Corresponding author: Dr. Gülfem Akin, Department of Dermatology, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey. glfmakin@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Avcı C, Akin G, Aydogan A, Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Aktan S. Successful use of rituximab in the treatment of severe childhood pemphigus accompanying phenylketonuria: A case report. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1252_2023

Dear Editor,

Childhood pemphigus vulgaris is a pediatric variant of pemphigus vulgaris characterised by skin and mucous membrane blisters and erosions.1 Managing protein loss can be challenging in pemphigus vulgaris patients associated with phenylketonuria (PKU). Here, we describe a 10-year-old girl with phenylketonuria (PKU) and severe childhood pemphigus vulgaris who did not respond to high-dose corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) but improved after rituximab infusion.

This child presented with generalised blisters, erosions, conjunctivitis, and oral lesions that persisted for 5 months. She was on a phenylalanine-restricted diet and used sapropterin dihydrochloride to lower phenylalanine levels.

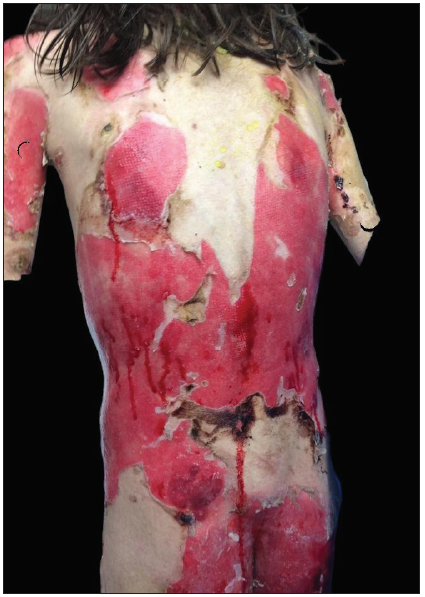

Physical examination revealed flaccid blisters and extensive erosions on her trunk and extremities, covering approximately 45% of her body surface area [Figures 1a and 1b]. Her oral intake was limited due to painful oral mucosal involvement. The Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) activity score was 168. Laboratory tests showed mild anaemia (11.2 g/dL), eosinophilia (0.7x103/µL), thrombocytosis (513x103/µL), hypoalbuminemia (2.2 g/dL) and elevation in C-reactive protein (24.4 mg/dL; normal range: 0.2–5).

- Extensive erosions on posterior trunk and lower extremities.

- Erosions covered by haemorrhagic crusts on lips and periorbital areas.

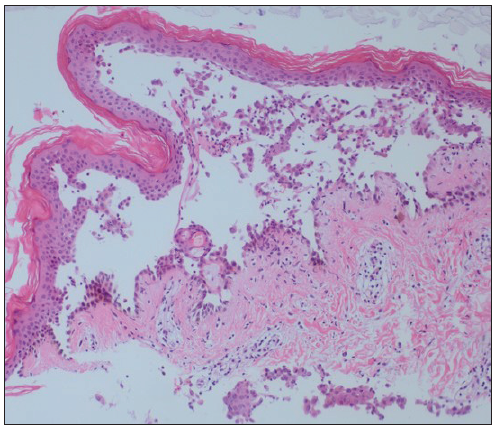

Skin biopsy specimens revealed suprabasal acantholysis [Figure 2] and direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular deposition of IgG in the epidermis. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay showed anti-BP180 negative, anti-BP230 2.11 ratio (>1 positive), anti-collagen tip VII negative, anti-Dsg1 negative, anti-Dsg3 10.09 ratio (>1 positive), and anti-envoplakin 1.94 ratio (>1 positive). Due to clinical severity and positive serological markers, malignancy screening was conducted to rule out paraneoplastic pemphigus. Tests included occult blood in faeces, peripheral smear, and protein electrophoresis. Imaging studies (chest X-ray, ultrasound for lymph nodes, abdominopelvic ultrasound, CT scans) showed no signs of solid tumours, hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy, nor atypical cells in peripheral blood smear.

- Suprabasal acantholysis with a row of tombstones (Haemotoxylin and Eosin, 40x)

After confirming the diagnosis, systemic prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) was initiated but yielded no response. Prednisone dosage was increased to 1.5 mg/kg/day, with monthly IVIG (2 g/kg). Due to limited oral intake and protein loss causing hypoalbuminemia, protein intake was raised to 55 g/day, with weekly blood phenylalanine monitoring. Serum albumin below 2 g/dL prompted two albumin infusions at 3-week intervals. Weekly blood phenylalanine levels ranged from 10 to 15 mg/dL initially, maintained at 6–8 mg/dL over 1 year.

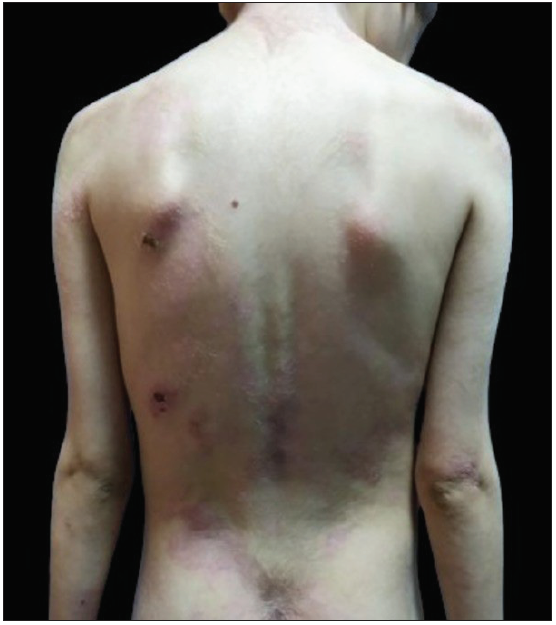

Despite 1 month of systemic corticosteroid therapy and two IVIG treatments, she showed no response, prompting rituximab administration (300 mg weekly for 4 weeks). Prednisolone was continued at 1.5 mg/kg/day, with a third round of IVIG. Tubular proteinuria after further IVIG led to its discontinuation. Lesions began to re-epithelise after the second rituximab infusion, with no new blisters. However, after the fourth infusion, she developed COVID-19 and recovered with supportive care. Prednisolone was gradually tapered by 5 mg monthly, but oral lesions remained resistant. Six months post-rituximab, a relapse occurred, necessitating a maintenance infusion (500 mg, iv). She has been in remission for the past 7 months [Figures 3a and 3b].

- Resolution of skin lesions at 12 months post-treatment.

- Resolution of skin lesions at 12 months post-treatment.

Antibodies against BP230 and envoplakin, proteins of the plakin family, are typically found in paraneoplastic pemphigus patients.2 However, cases of pemphigus vegetans with periplakin antibodies and pemphigus vulgaris with anti-desmoplakin antibodies have been reported.3,4 Despite this, no underlying malignancy was detected. In our patient, initial tissue damage from anti-desmoglein 3 may have led to an epitope-spreading phenomenon, resulting in antibodies against plakin family proteins.

While PKU is associated with various autoimmune disorders, childhood pemphigus vulgaris has not been reported.5 The coexistence of pemphigus vulgaris and PKU may reflect the susceptibility of PKU patients to autoimmune diseases.

Maintaining protein balance in severe childhood pemphigus vulgaris patients on a phenylalanine-restricted diet is challenging. Protein loss from skin lesions can lead to electrolyte imbalance and hypovolemic shock. To maintain the patient’s albumin level in balance, it is suggested to measure the albumin level closely and, if necessary, replace albumin and increase daily protein intake under weekly blood phenylalanine level monitoring.

Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment in childhood pemphigus vulgaris in conjunction with steroid-sparing agents.6 Steroid-related side effects limit its long-term use in childhood.1 Some cases may be refractory, requiring additional therapies. Long-term follow-up is crucial due to relapses.6

Rituximab, recommended alongside systemic prednisolone for moderate-to-severe adult pemphigus vulgaris, shows growing evidence of safety and efficacy in childhood pemphigus vulgaris, despite limited data on its use in this population.1,6

Despite concerns about immunosuppression during the COVID-19 pandemic, rituximab was deemed necessary due to the severe and refractory nature of the patient’s pemphigus.

Except for one patient with phenylketonuria and pemphigus foliaceus reported by Scheinfeld, to our knowledge, PKU with childhood pemphigus vulgaris has not been reported in the literature.7 The management of protein deficiency and the efficacy of rituximab in a severe childhood pemphigus vulgaris case resistant to conventional corticosteroid treatment during the pandemic is highlighted in this case report.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Pediatric autoimmune blistering disorders – A five-year demographic profile and therapy experience. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1511-18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus: A clinical, laboratorial, and therapeutic overview. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:388-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pemphigus vegetans Neumann type with anti-desmoglein and anti-periplakin autoantibodies. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:530-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucosal dominant pemphigus vulgaris with anti-desmoplakin autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:62-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The challenges of managing coexistent disorders with phenylketonuria: 30 cases. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:242-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Successful use of rituximab in the treatment of childhood and juvenile pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:669-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case of co-incident phenylketonuria, pemphigus foliaceus, and tinea amiantacea treated with tetracycline and nicotinamide. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:202-5.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]