Translate this page into:

A child’s cry: Hematohidrosis - Unmasked by surgical trauma

Corresponding author: Dr. Sahana Srihari, Department of Dermatology, Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India. drsahanasrihari@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Srihari S, Iyer SK, Tayal R, Goyal V. A child’s cry: Hematohidrosis - Unmasked by surgical trauma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2025;91:S50-S51. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1407_2023

Dear Editor,

Hematohidrosis is a rare medical condition where blood is excreted through intact, unbroken skin.1 It is thought to result from the rupture of tiny blood vessels supplying the sweat glands during periods of extreme emotional or physical stress. This condition presents as recurrent episodes of spontaneous bloody discharge and has been associated with systemic issues such as thrombocytopenic purpura and vicarious menstruation.2–4 The spectrum of hematohidrosis includes documented cases of bleeding from the skin, eyes (hemolacria)5 and ears (blood otorrhea).6 Although it is rare, the condition has been recorded in a limited number of cases, with the largest study to date reporting just 25 cases between 1996 and 2016.7

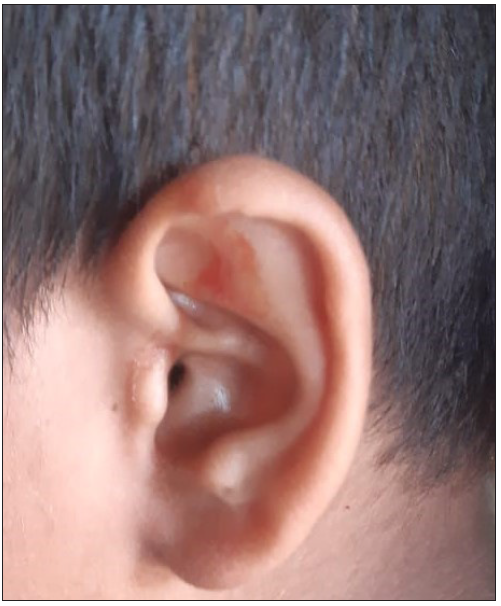

A ten-year-old boy presented at the dermatology outpatient department with a distressing complaint of recurrent bleeding from his cheeks, eyelids [Figure 1] and ears [Figure 2] since the past two months. Remarkably, there were no reports of bleeding from any other sites. The child had recently undergone septoplasty following which there was a prolonged period of absence from school and a marked change in his demeanour. He exhibited heightened irritability, frequent temper tantrums and voluntary social isolation. Over the subsequent weeks, he experienced recurrent episodes of bleeding from the intact skin around his eyes (non-conjunctival) and ears, including the skin around the ear canal and cheek. These episodes increased in frequence to become a daily occurrence, characterised by spontaneous, painless bleeding lasting from mere seconds to a few minutes. The bleeding was of a non-spurting nature and it subsided with gentle pressure or simple wiping. The school authorities, concerned about his condition, prohibited him from attending school which aggravated the stress in this otherwise fun-loving and diligent child. Clinically, there were no discernible scars or breaks in the skin surface. The child did not lose consciousness, experience a drop in blood pressure or develop syncope during these episodes. There was no concurrent physical illness, history of trauma or the use of illicit substances. Notably, he experienced these episodes during periods of heightened stress. The child’s medical history was unremarkable, with no known allergies to medications or foods or past occurrences of similar complaints, systemic illnesses or bleeding tendencies. There was no family history. On examination, he was alert and conversed well. His general physical condition, cutaneous and systemic examinations were within normal limits. His haematological investigations were within normal limits. Peripheral smear examination revealed normal red blood cell morphology. Benzidine test yielded a positive result when applied to the secretion sample. To address his condition, the patient was advised to employ relaxation techniques, prioritise rest, engage in meditation practices and make lifestyle adjustments. Additionally, he was prescribed dose of propanolol used was 10mg once daily for 3 months. During the follow-up visit after a fortnight, the patient reported feeling better with fewer episodes and no episodes were reported after eight weeks. In conjunction with propranolol, the child received counselling and specific meditation techniques that led to the maintenance of remission. Consequently, the duration and frequency of bleeding episodes diminished, to occur sporadically every few weeks. The boy successfully completed the regimen with controlled bleeding episodes sustained for at least one year leading to parents’ satisfaction as well.

- Sweat admixed with blood on the eyelids.

- Sweat admixed with blood from the left ear pinna.

Hematohidrosis, also known as hematidrosis and hematofolliculohidrosis, is a notable medical disorder in which a person excretes blood through their intact skin. This ailment is officially recognised in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD9-CM 705-89).7 The term ‘Hematohidrosis’ is derived from the Greek terms ‘haima/haimatos’, which means blood, and ‘hidros’, which means sweat. It is thought to result from the rupture of tiny blood vessels supplying the sweat glands during periods of extreme emotional or physical stress. This happens when a person experiences extreme mental or physical stress, resulting in the unusual release of blood through the skin.1 Although there is no established cure for hematohidrosis, the available therapeutic options consist of beta blockers, anxiolytics, and other psychological therapies. These interventions have shown promising results in alleviating the symptoms within a year of starting treatment, as reported in existing studies. We present this report due to its rarity, with the aim of further enhancing and clarifying the knowledge of hematohidrosis, a peculiar and perplexing phenomenon. Recognising the beneficial influence that counselling and modifications to one’s lifestyle may have on the overall state of well-being in these individuals is crucial.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- I am anxious, I bleed – A rare clinical case of facial hematohidrosis. Clin Dermatol Rev. 2023;7:383-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Child who presented with facial hematohidrosis compared with published cases. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;7:123-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of primary thrombocytopenic purpura by modified minor decoction of bupleurum. J Tradit Chin Med. 1995;15:96-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microscopically and chemically detected haemolacria. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1977;55:132-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blood otorrhea: blood-stained sweaty ear discharges: Hematohidrosis; four case series (2001–2013) Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:271-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hematidrosis (bloody sweat): A review of the recent literature (1996–2016) Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:85-90.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hematohidrosis: A rare case of a female child who sweat blood. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18:327-9.

- [Google Scholar]