Translate this page into:

Clinical and dermoscopic profile of non-venereal genital dermatoses and its impact on the quality of life: A cross-sectional study of 550 cases

Corresponding author: Dr. Anupama Bains, Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. whiteangel2387@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sadhukhan S, Bains A, Bhardwaj A, Patra S, Vedant D, Sharma C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic profile of non-venereal genital dermatoses and its impact on the quality of life: A cross-sectional study of 550 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_776_2024

Abstract

Background

Non-venereal genital dermatoses cover a broad spectrum of conditions with varying aetiologies and can be confused with venereal disorders. This may cause significant anxiety to the patient as well as diagnostic difficulties for the clinician.

Objective

The purpose was to study the clinico-epidemiological pattern of non-venereal genital dermatoses along with their dermoscopic features and to assess their impact on the quality of life.

Methods

This was a prospective, cross-sectional, observational study of 503 consecutive adult patients with non-venereal genital dermatoses. Relevant history and clinical examination, dermoscopy findings were documented and histopathology was performed where indicated. Statistical analyses was done using SPSS software v.23.

Results

Five hundred and three individuals with non-venereal genital lesions were enrolled. Some patients had multiple dermatoses, so a total of 550 cases were analysed. Men outnumbered women (5.8:1). A total of 49 different non-venereal genital dermatoses were identified. The most common ones were scabies 97 (17.6%), vitiligo 54 (9.8%), lichen simplex chronicus 43 (7.8%), lichen sclerosus 43 (7.8%) and lichen planus 39 (7.1%). Other dermatoses included psoriasis, Zoon’s balanitis, lichen nitidus, angiokeratoma and idiopathic scrotal calcinosis. Physiological conditions were noted in 56 (10.2%) cases, while 5 (1%) cases were premalignant and malignant disorders. The commonest symptom was genital pruritus 337 (60.9%). Scrotum was most frequently affected site in men (54.6%) and labia majora in women (81.6%). Comparative analysis between the dermoscopic features of similar-looking disorders like vitiligo versus lichen sclerosus, scrotal dermatitis versus psoriasis and lichen planus versus psoriasis was statistically significant (p<0.05). There was a large effect on the quality of life in 8(1.5%), moderate effect in 87(16.2%) and small effect in 385 (71.8%) patients. Dermatology life quality index was significantly elevated in women. Seventy six (15.1%) patients suffered from venerophobia.

Limitations

Because of the cross-sectional study design, dermatoscopic examinations were performed at various phases of the diseases. Histopathology was performed in a limited number of cases, so findings on dermoscopy and histopathology could not be correlated.

Conclusion

Non-venereal genital dermatoses are common and more so among men. The most common dermatoses noted was scabies followed by vitiligo and lichen simplex chronicus. The present study provides detailed clinical and dermoscopy features in Indian patients. Dermoscopy is a useful tool in the diagnosis of these diseases. These dermatoses have mild to moderate effects on patients’ quality of life; some of these patients suffer from venereophobia. Recognising and treating this issue will aid in properly managing these patients.

Keywords

Dermoscopy

genital disease

non-venereal genital dermatoses

Introduction

Non-venereal genital dermatoses are those genital dermatoses which are not sexually transmitted.1 Based on aetiology, non-venereal genital dermatoses are broadly classified into three types: physiological conditions, infections and infestations, and non-infectious diseases. Non-venereal genital dermatoses may cause emotional distress and interpersonal issues, especially if they are noticed after sexual intercourse.2 Assessing the impact of these dermatoses on the quality of life can help in providing appropriate treatment and counselling services.2

The scope of dermoscopy is vast and it is being currently utilised to examine diseases of the mucosa (mucoscopy).3 Due to concerns about spreading infection, dermatologists were hesitant to perform regular mucoscopy. Innovative solutions, such as the usage of cling film and barrier footplates, have now allayed these concerns.3 By providing a better view of the lesions, it may prevent unnecessary biopsies.

The aim of the present study was to determine the clinical and epidemiological pattern of non-venereal genital dermatoses, describe their dermoscopy findings and determine their impact on the quality of life.

Methods

This was a prospective, cross-sectional observational study conducted in the Dermatology outpatient department and also included cases referred from the Gynaecology and Urology departments, done over a period of 18 months from September 2021 to March 2023, after obtaining approval from Institutional Ethics Committee (Certificate reference no. AIIMS/IEC/2021/3597 dated 06/09/2021).

All patients with external genital lesions with or without extragenital lesions were included after obtaining informed consent. Patients who were partially treated or taking treatment from outside, and those presenting with a venereal disease diagnosed clinically or based on laboratory investigations (HIV, HbsAg, Anti HCV and RPR) were excluded from the study.

Detailed history and clinical examination were recorded in a structured proforma. Detailed sexual history regarding number of partners, practices, frequency and last exposure, protected or unprotected or influence of intoxicating agent if any, contraception practices, past history of STD in self and partner were recorded. A baseline clinical image of lesions was taken. The dermoscopy examination was performed by two authors (SS and AB) to maintain the uniformity in evaluation using a manual hand-held dermotoscope Heine delta 30 at 10× magnification, polarised mode and 12 megapixels (MP) mobile camera was used for photographic documentation. Disposable overhead projector transparent sheets were used between the dermotoscope lens and genital skin to maintain hygiene and avoid transmission of infections. Further relevant investigations like skin biopsy were done where indicated. The impact of disease on the quality of life was assessed by a dermatology life quality index questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed in the form of numbers and percentages. Quantitative data with normal distribution were presented as means ± SD. To determine the statistical differences in quantitative variables, t-test and one-way ANOVA test were employed. The final data analysis was done using SPSS ver. 23 software and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of 93,399 outpatients examined during the 18-month study period, the total number of patients who came with genital complaints was 939, of which 427 (45.5%) were sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and 512 (54.5%) were non-venereal genital dermatoses. Out of these 512 patients, 9 cases were inconclusive (where final diagnosis could not be reached on clinical and histological assessment) and 503 patients fulfilling inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited in the study. Among these 503 patients, a total of 44 patients were referred from Gynaecology and Urology department. Excluding these referred cases, the overall prevalence of non-venereal genital dermatoses was found to be 49.1 per 10,000 dermatology outpatients. The age of the patients ranged from 4 months to 87 years with a mean age of 34.9 ± 16.5 years. Most patients belonged to the age group of 20–29 years (n=154, 30.6%). Males (n=429 patients) outnumbered females (n=74 patients) in a ratio of 5.8:1. Most of the patients (n=299, 59.4%) were married and resided in rural regions (n=283, 56.2%).

Four hundred and fifty-seven patients (90.9%) had single dermatoses, whereas multiple dermatoses were found in 46 patients (9.1%). Hence, a total of 550 cases were counted in the final analysis.

Dermoscopic features corroborated the clinical diagnosis in 407 (74%) cases and histopathology was done for 59 (10.7%) doubtful cases for confirmation of the diagnosis.

A total of 49 different dermatoses were noted in this study [Table 1]. The most common group of dermatoses was infections and infestations 126 (22.9%), of which scabies was the most common disease 97 (17.6%). It was followed in frequency by eczematous disorders 78 (14.2%), miscellaneous disorders 76 (13.8%), physiological conditions 56 (10.2%) and vitiligo 54 (9.8%).

| S. no | Disease | Male | Female | Total [n=550] (%) | DLQI [n=537] | Venereophobia [n=76] (% of respective diseases) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range (Min-Max) | ||||||

| Physiological conditions [n=56, (10.2%)] | |||||||

| 1. | Pearly penile papules | 23 | 0 | 23 (4.2) | 3 ± 2.0 | 0–8 | 9 (39.1) |

| 2. | Melanosis | 22 | 0 | 22 (4) | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 0–7 | 1 (4.5) |

| 3 | Fordyce spots | 10 | 0 | 10 (1.8) | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 0–8 | 8 (80) |

| 4 | Benign vulvar vestibular papillomatosis | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 8 | - | 1 (100) |

| Infections and infestations [n=126, (23%)] | |||||||

| 5 | Scabies | 95 | 2 | 97 (17.6) | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 1–7 | 0 (0) |

| 6 | Candidiasis | 9 | 4 | 13 (2.4) | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 1–7 | 2 (15.4) |

| 7 | Tinea cruris | 8 | 1 | 9 (1.6) | 3 ± 1.3 | 2–6 | 1 (11.1) |

| 8 | Pityriasis versicolor | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 3 | - | 0 (0) |

| 9 | Mucormycosis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 5 | - | 0 (0) |

| 10 | Pyoderma | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 3 ± 0.0 | 3–3 | 0 (0) |

| 11 | Surgical site infection | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 7 ± 2.8 | 5–9 | 0 (0) |

| 12 | Necrotising fasciitis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 8 | - | 0 (0) |

| Eczematous disorders [n=78, (14.2%)] | |||||||

| 13 | Lichen simplex chronicus | 33 | 10 | 43 (7.8) | 4.3 ± 1.6 | 1–8 | 2 (4.7) |

| 14 | Scrotal dermatitis | 22 | 0 | 22 (4) | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 1–10 | 0 (0) |

| 15 | Irritant contact dermatitis | 11 | 0 | 11 (2) | 4.4 ± 2.4 | 2–9 | 0 (0) |

| 16 | Atopic dermatitis | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| 17 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 2 | - | 0 (0) |

| Papulosquamous disorders [n=33, (6%)] | |||||||

| 18 | Psoriasis | 25 | 8 | 33 (6) | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 1–9 | 1 (3) |

| Lichenoid disorders [n=47, (8.5%)] | |||||||

| 19 | Lichen planus | 37 | 2 | 39 (7.1) | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 1–6 | 17 (43.6) |

| 20 | Lichen nitidus | 8 | 0 | 8 (1.4) | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 2–7 | 4 (50) |

| Sclerosing disorders [n=43, (7.8%)] | |||||||

| 21 | Lichen sclerosus | 23 | 20 | 43 (7.8) | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 1–11 | 4 (9.3) |

| Neutrophilic dermatoses [n=3, (0.5%)] | |||||||

| 22 | Behcet’s disease | 2 | 1 | 3 (0.5) | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5–6 | 2 (66.7) |

| Vesiculobullous disorders [n=2, (0.4%)] | |||||||

| 23 | Pemphigus vulgaris | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 6–7 | 0 (0) |

| Drug reactions [n=9, (1.6%)] | |||||||

| 24 | Fixed drug eruption | 5 | 0 | 5 (0.9) | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 5–8 | 0 (0) |

| 25 | Stevens-Johnson syndrome | 2 | 2 | 4 (0.7) | 11.7 ± 2.2 | 10–15 | 0 (0) |

| Pigmentary disorders [n=54, (9.8%)] | |||||||

| 26 | Vitiligo | 48 | 6 | 54 (9.8) | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 0–7 | 6 (11.1) |

| Vascular lesions [n=18, (3.3%)] | |||||||

| 27 | Angiokeratoma | 14 | 2 | 16 (2.9) | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 1–7 | 1 (6.3) |

| 28 | Vulvar varicosities | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.4) | 0.50 ± 0.7 | 0–1 | 0 (0) |

| Premalignant and malignant [n=5, (1%)] | |||||||

| 29 | Bowen’s disease | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 3 | - | 0 (0) |

| 30 | Pseudoepitheliomatous keratotic and micaceous balanitis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 10 | - | 0 (0) |

| 31 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 6–7 | 1 (50) |

| 32 | Cutaneous metastasis | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 6 | - | 0 (0) |

| Miscellaneous [n=76, (13.8%)] | |||||||

| 33 | Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis | 27 | 0 | 27 (4.9) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1–6 | 2 (7.4) |

| 34 | Steatocystoma | 7 | 1 | 8 (1.4) | 3.6 ± 3.6 | 0–11 | 1 (12.5) |

| 35 | Cutaneous horn | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 | - | 0 (0) |

| 36 | Zoon’s balanitis | 20 | 0 | 20 (3.6) | 3.8 ± 2.1 | 1–10 | 10 (50) |

| 37 | Circinate balanitis | 4 | 0 | 4 (0.7) | 6.2 ± 3.3 | 4–11 | 2 (50) |

| 38 | Lymphangiectasia | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1–2 | 0 (0) |

| 39 | Seborrheic keratosis | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 3 ± 2.8 | 1–5 | 1 (50) |

| 40 | Porokeratosis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 | - | 0 (0) |

| 41 | Verrucous epidermal naevus | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| 42 | Incontinentia pigmenti | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| 43 | Systemic lupus erythematous | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 7 | - | 0 (0) |

| 44 | Lipschutz ulcer | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 10 | - | 0 (0) |

| 45 | Calciphylaxis | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 11 | - | 0 (0) |

| 46 | Genital Crohn’s disease | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.4) | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 5–8 | 0 (0) |

| 47 | Angiomyxoma | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 11 | - | 0 (0) |

| 48 | Pseudodfolliculitis | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 1 | - | 0 (0) |

| 49 | Topical steroid induced atrophy | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2–3 | 0 (0) |

DLQI: Dermatology life quality index

Among males (474 cases), the most common dermatosis noted was scabies 95 (20%) followed by vitiligo 48 (10.1%) and lichen planus 37 (7.8%). In females (76 cases), the most common dermatosis was lichen sclerosus 20 (26.3%) followed by lichen simplex chronicus 10 (13.1%).

In males (n=474 cases), scrotum (260/474, 54.6%) was the most common site of involvement and in females (n=76 cases), commonest site was labia majora (62/76, 81.6%).

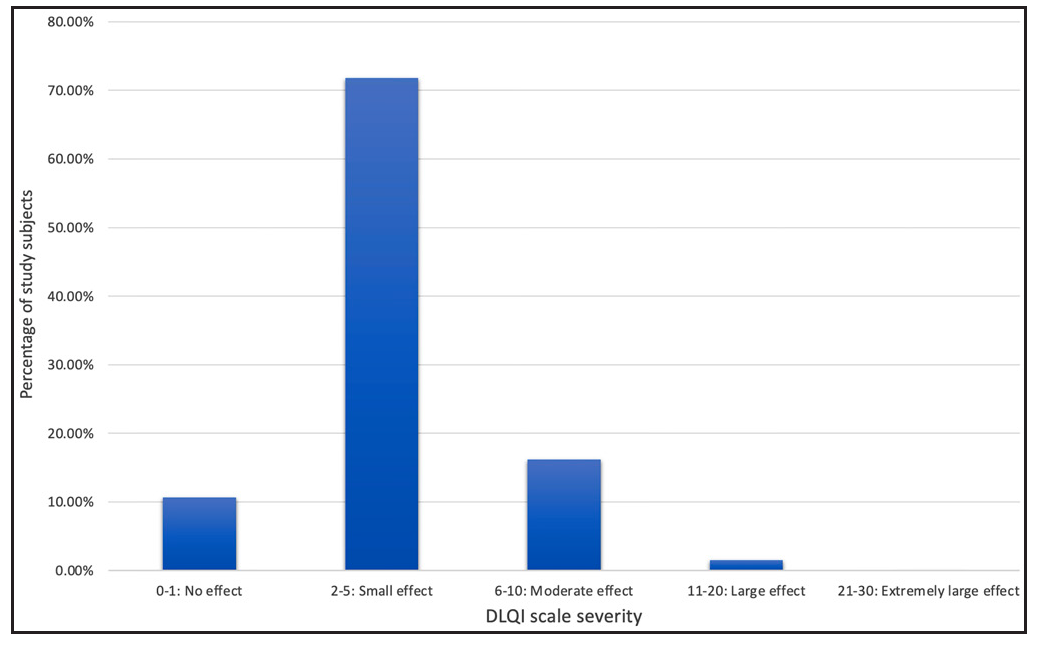

Quality of life was calculated for 537 cases [Figure 1] and it was adversely affected in 527 (98.1%) patients. There was a large effect in 8 (1.5%), moderate effect in 87 (16.2%) and small effect in 385(71.8%) patients. Fifty-seven (10.7%) cases were not bothered by the illnesses. DLQI was significantly increased in females than males. When DLQI in individual dermatoses were calculated [Table 1], it was noticed that angiomyxoma of the vulva, pseudoepitheliomatous keratotic and micaceous balanitis (PKMB) and Lipschutz ulcer had a significant impact on the quality of life. Premalignant and malignant diseases had moderate impact. However, lichen sclerosus had a moderate impact and chronic conditions like psoriasis, lichen planus, vitiligo and Zoon’s balanitis had a small impact on daily activities.

- Percentage of study subjects (y-axis) categorised by severity of dermatology life quality index (x-axis).

A total of 76 (15.1%) patients had venerophobia and out of them, 74 were men (17.2% of total male patients). A total of 20 diseases had some components of venerophobia [Table 1]. A few physiological conditions like benign vulvar vestibular papillomatosis, Fordyce spots, pearly penile papules and chronic inflammatory conditions like Zoon’s balanitis and lichen planus had a significant degree of venerophobia.

The clinical and dermoscopic features of individual dermatoses are described below.

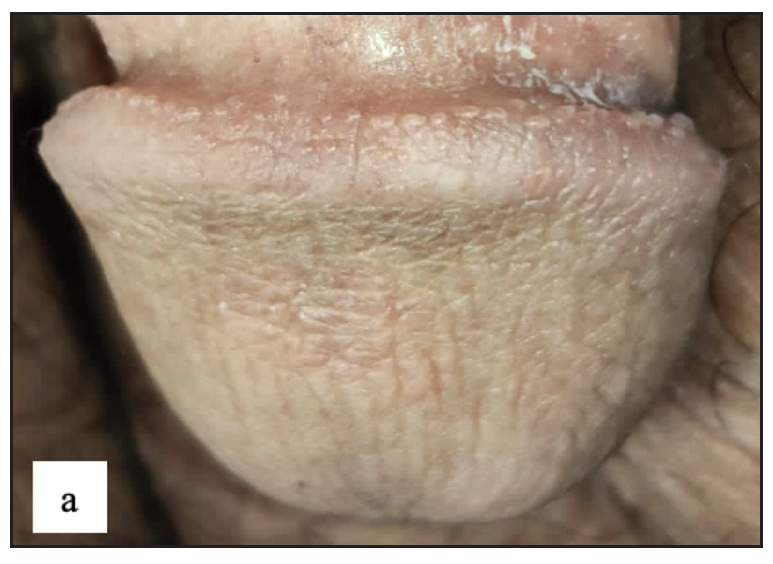

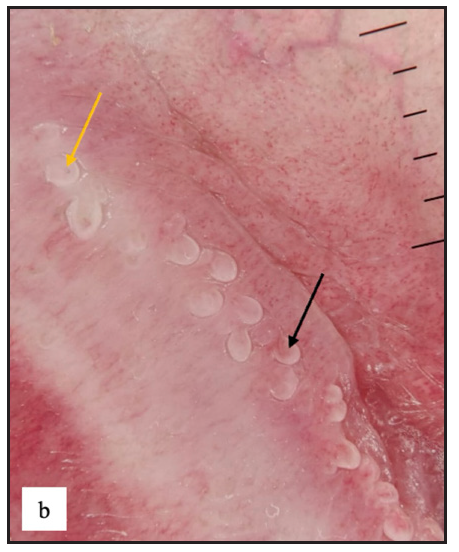

Pearly penile papules

A total of 23 (4.2%) cases of pearly penile papules were observed. Clinically, patients presented with pearly white round discrete 1–2 mm sized papules circumferentially over the coronal sulcus in a single or double row and were most prominent over the dorsolateral aspect [Figure 2a]. Dermoscopic examination revealed white to pinkish cobblestone appearance (n=23, 100%), central curved vessel (n=15, 65.2%) and dotted vessel (n=13, 56.5%) [Figure 2b].

- Pearly penile papule presenting as 1–2 mm pearly white coloured dome-shaped translucent papules over the coronal sulcus.

- Dermoscopy of pearly penile papules showed white cobblestone appearance with central comma-shaped vessels (black arrow) and brown dots (yellow arrow).

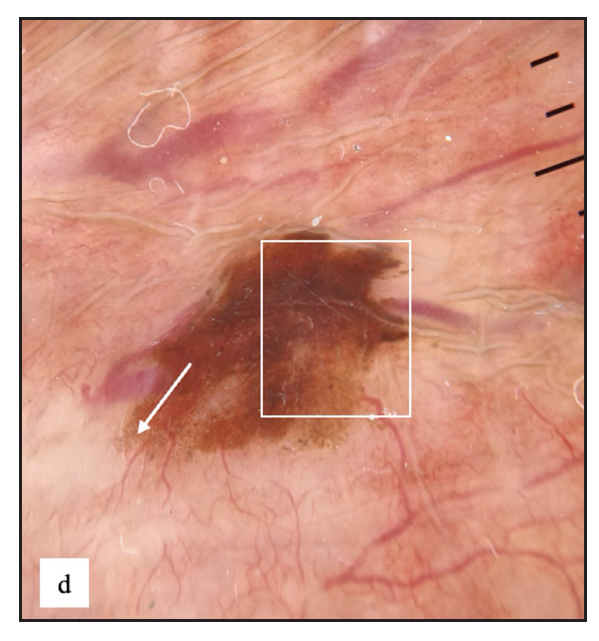

Genital melanosis

Twenty-two males (4%) complained of melanosis on the external genitalia. All patients presented with asymptomatic brown to black well-defined single to multiple hyperpigmented macules, most commonly over the penile shaft in 20 (90.9%) cases [Figure 2c]. The most common dermoscopic parameter was brown structureless areas that were characterised by different shades of brown to black in 21 (95.5%) cases and black dots in 11 (50%) cases [Figure 2d].

- Genital melanosis characterised by well-defined brown to black coloured round macule over penile shaft.

- Genital melanosis dermoscopy revealed brown structureless areas with irregular feathery margin (white square) and dots, globules (white arrow).

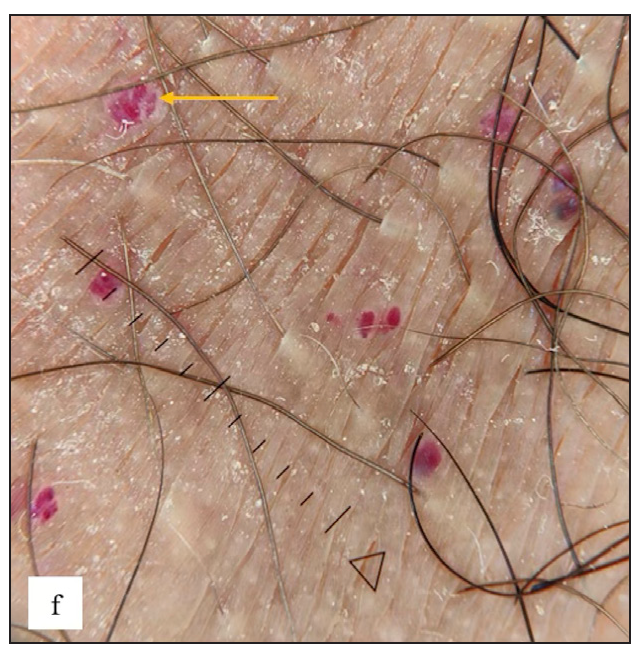

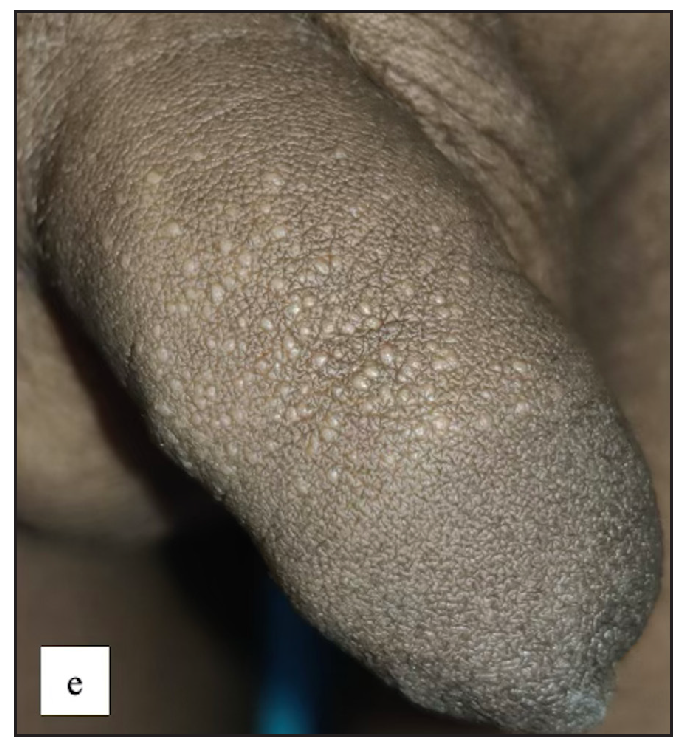

Fordyce spots

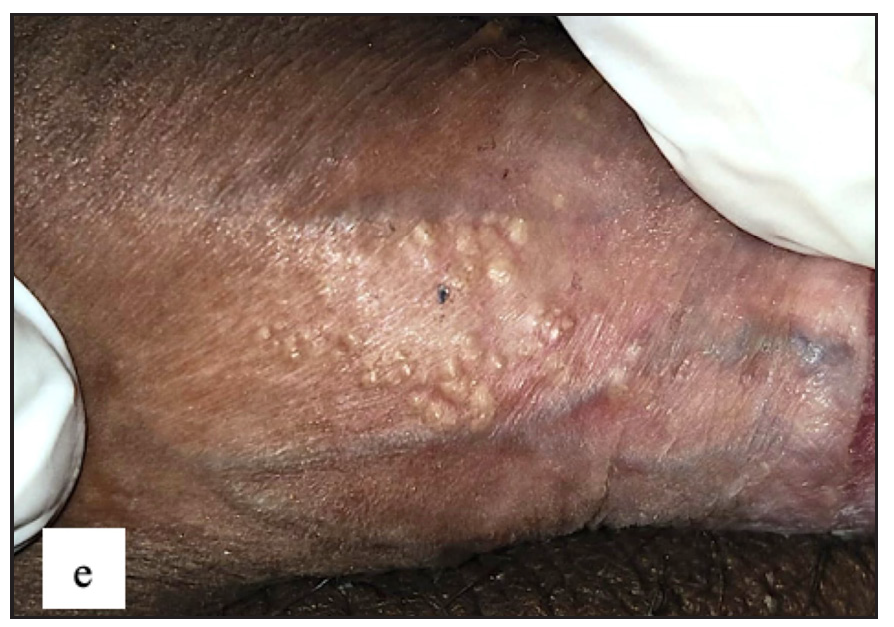

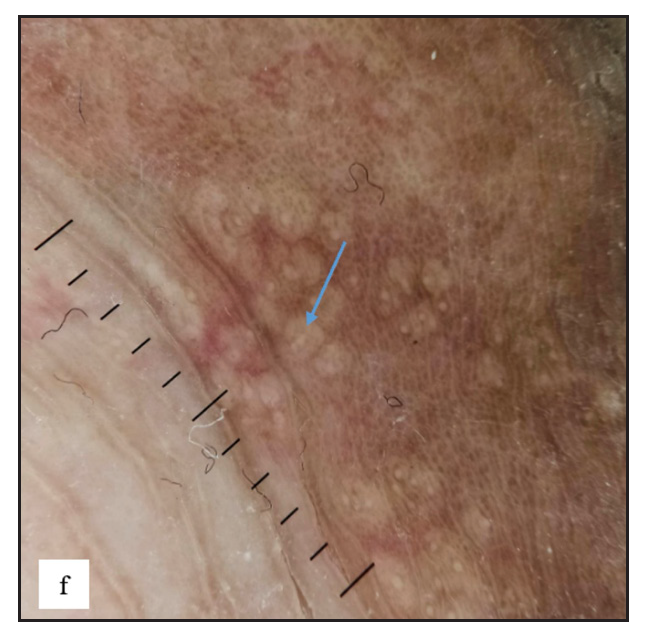

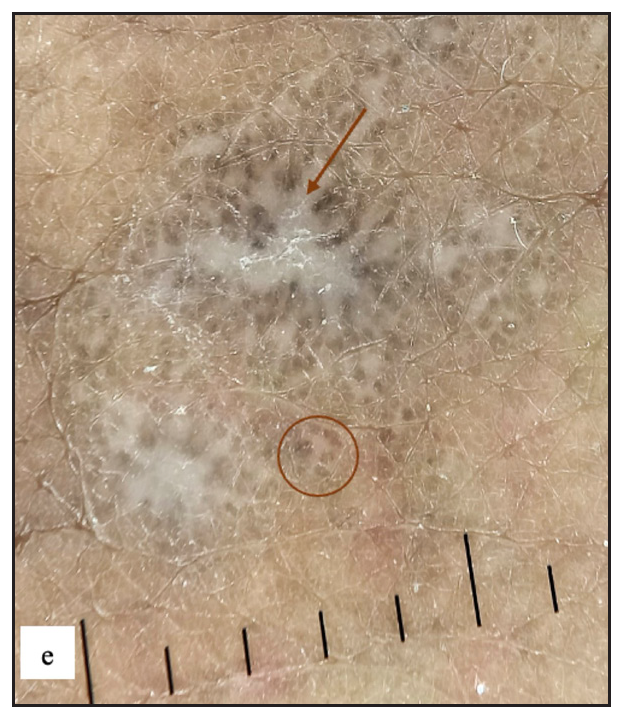

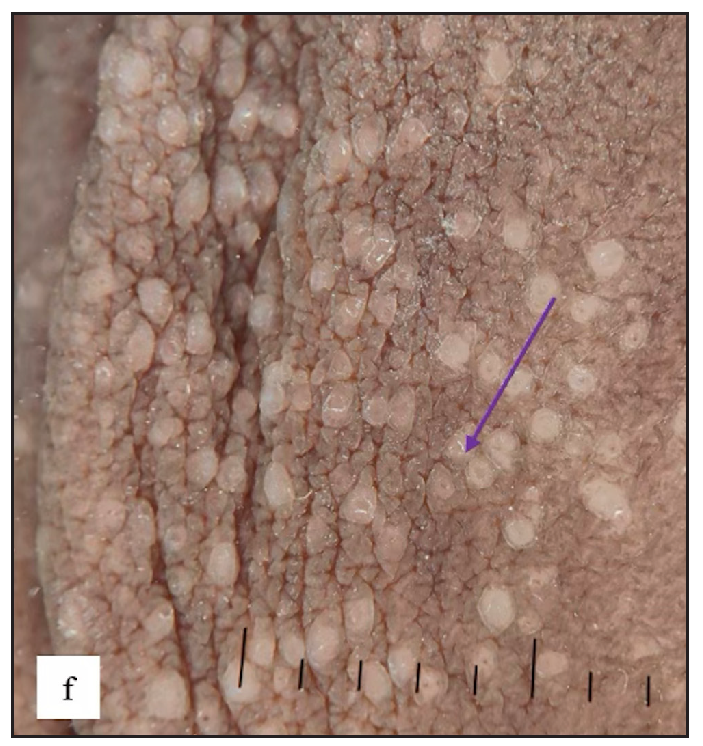

Fordyce spots were observed in 10 (1.8%) cases. Multiple, discrete, whitish-yellow, pinhead-sized barely elevated papules were seen in a grouped fashion over the penile shaft in nine and the prepuce in two cases [Figure 2e]. Extragenital involvement of lips and buccal mucosa was noted in three cases. Dermoscopy showed white to yellow ovoid structures with central opacity in all cases which were occasionally surrounded by straight vessels (10%) [Figure 2f].

- Fordyce spots showing discrete yellowish-grouped papules are present over the penile shaft.

- Dermoscopy of Fordyce spots depicting yellow ovoid structures with central opacity (blue arrow).

Scabies

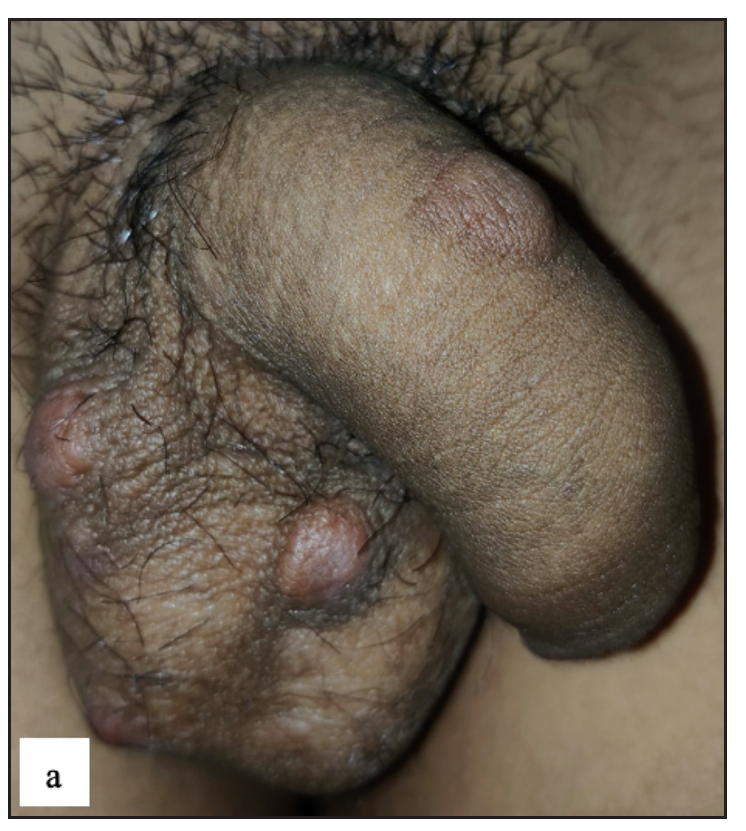

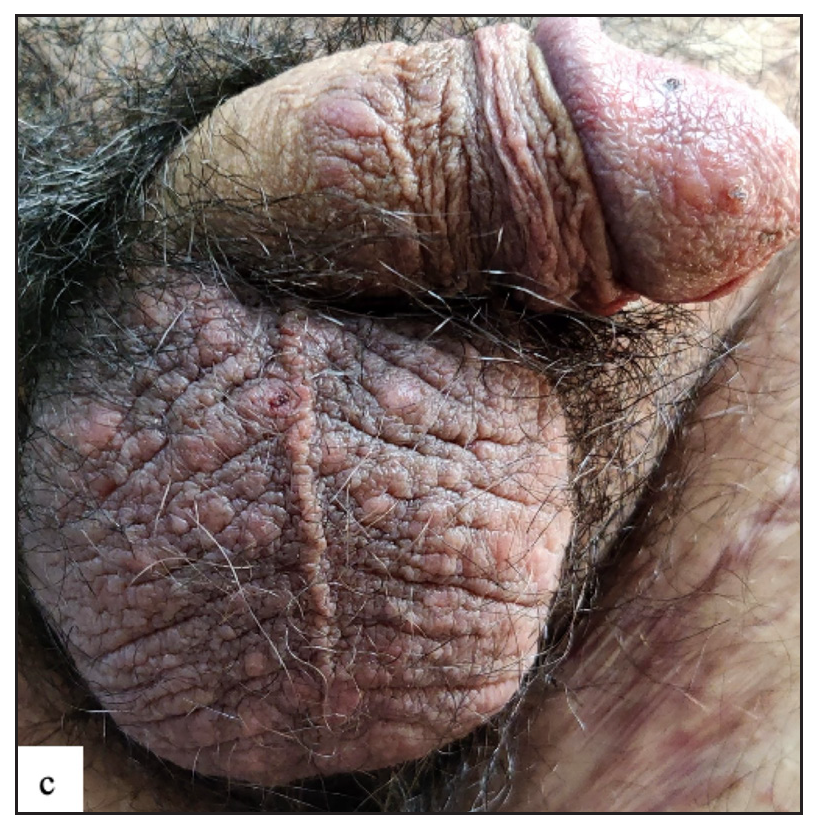

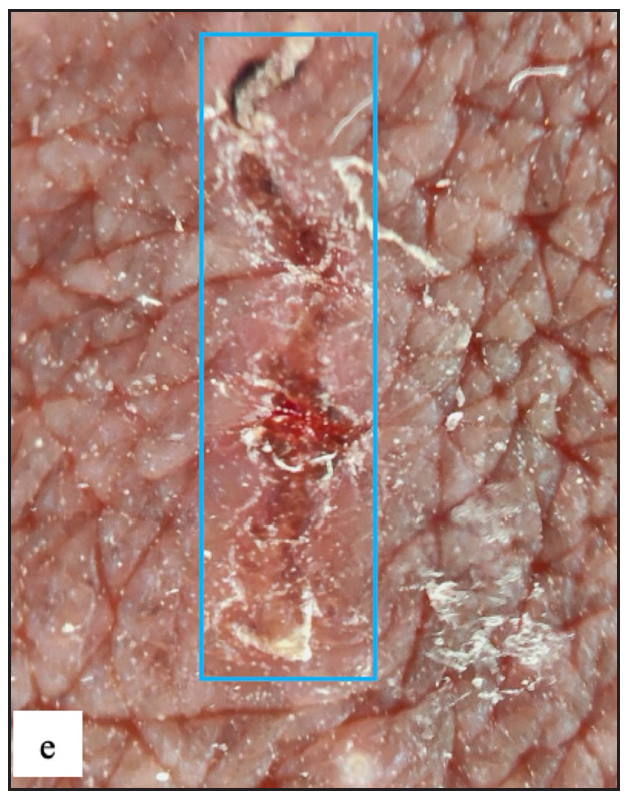

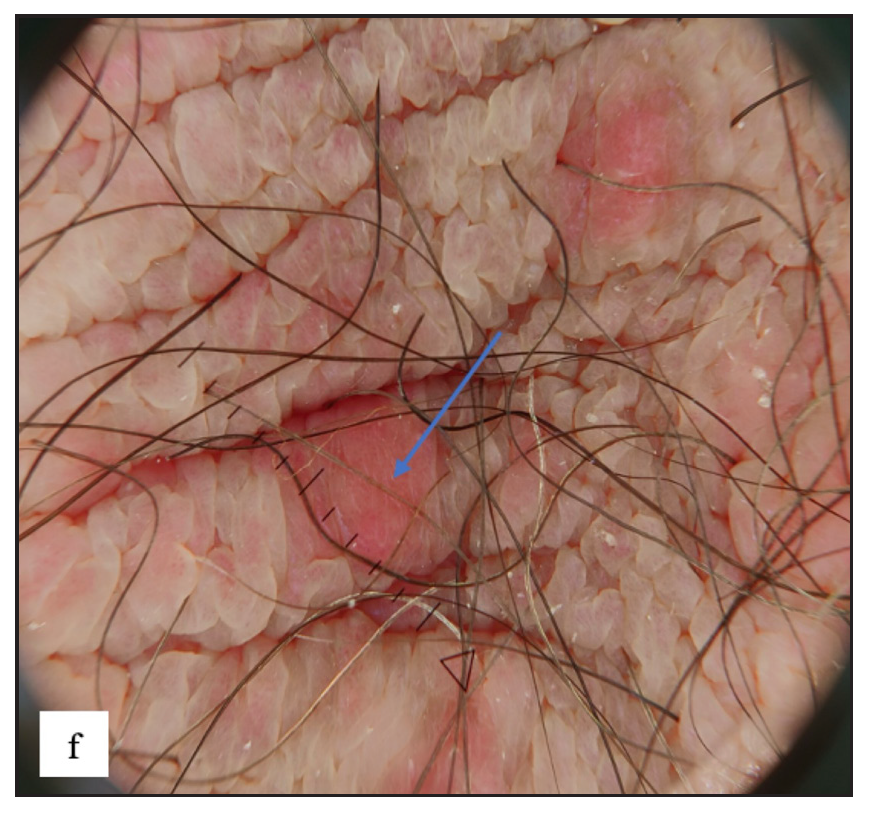

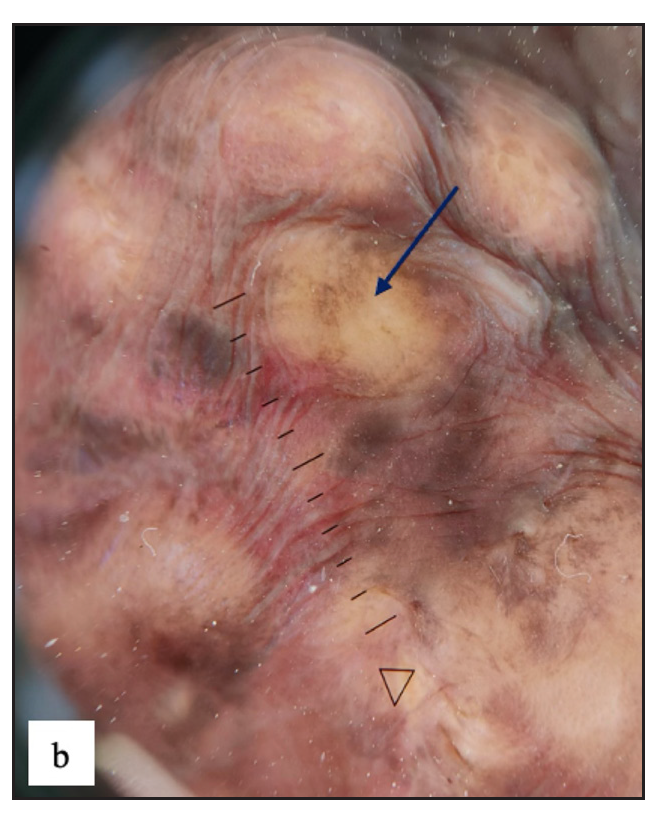

Scabies was the most common disease noted in the study, constituting 97 (17.6%) of cases. Ninety-five (97.9%) of these cases were male. Twenty-four (24.7%) of the cases had isolated genital involvement while the rest had extragenital lesions also. The most common site involved in males was the scrotum (87, 91.5%) while labia majora was the most common site involved in females (2, 100%). The most common morphology found was discrete erythematous 2–4 mm sized papules in 96 (99%) cases [Figure 3a, 3b and 3c]. Dermoscopic examination revealed red structureless areas in 89 (91.8%) cases with white scales in 62 (63.9%). Serpiginous tracts which are specific to scabies were found only in 20 (20.6%) cases [Figure 3d, 3e, 3f and Table 2].

- Various lesions of genital scabies. Multiple well-defined erythematous large nodules over the penile shaft and scrotum.

- Multiple excoriated papules and burrows over the penile shaft.

- Various lesions of genital scabies. Numerous scattered erythematous papules over genitalia.

- Dermoscopy revealed red structureless areas, dotted vessels and white-yellow scales (blue circle).

- Serpiginous tract with haemorrhagic crusts and peripheral scales was seen in dermoscopy of burrows (blue square).

- Scabetic nodules dermoscopy showed red structureless areas (blue arrow).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Genital scabies (n = 97) | ||

| Red structureless area | 89 | 91.8 |

| White scales | 62 | 63.9 |

| Dotted vessels | 51 | 52.6 |

| Patchy scales | 38 | 39.2 |

| Haemorrhagic crusts | 35 | 36.1 |

| Brown dots and globules | 34 | 35.1 |

| Central scales | 33 | 34 |

| Serpiginous tracts | 20 | 20.6 |

| Yellow crusts | 16 | 16.5 |

| Yellow scales | 13 | 13.4 |

| Peripheral scales | 11 | 11.3 |

| Background erythema | 9 | 9.3 |

| Brown scales | 5 | 5.2 |

| Erosions | 5 | 5.2 |

| Straight vessels | 1 | 1 |

| Wavy vessels | 1 | 1 |

| Genital psoriasis (n = 33) | ||

| Background erythema | 32 | 97 |

| Regular dotted vessels | 28 | 84.8 |

| White scales | 27 | 81.8 |

| Brown dots | 15 | 45.5 |

| Yellow scales | 6 | 18.2 |

| Brown globules | 4 | 12.1 |

| Genital lichen planus (n = 39) | ||

| Brown-blue dots | 31 | 79.5 |

| Purple structureless areas | 23 | 59 |

| Wickham striae | 20 | 51.3 |

| White scales | 12 | 30.8 |

| Brown globules | 9 | 23.1 |

| Grey reticular lines | 6 | 15.4 |

| Brown peripheral rim | 3 | 7.7 |

| Yellow scales | 2 | 5.1 |

| Grey peripheral rim | 2 | 5.1 |

| Red peripheral rim | 2 | 5.1 |

| Grey radial lines | 1 | 2.6 |

| Grey parallel lines | 1 | 2.6 |

| Dotted vessels | 1 | 2.6 |

| Lichen sclerosus (n = 43) | ||

| White structureless areas | 43 | 100 |

| Background erythema | 35 | 81.3 |

| Curved vessels | 21 | 48.8 |

| Looped vessels | 15 | 34.9 |

| Dotted vessels | 14 | 32.6 |

| Wavy vessels | 7 | 16.3 |

| Straight vessels | 5 | 11.6 |

| Branched vessels | 5 | 11.6 |

| White scales | 4 | 9.3 |

| Erosions | 4 | 9.3 |

| Brown dots | 1 | 2.3 |

| Genital vitiligo (n = 54) | ||

| White structureless areas | 53 | 98.1 |

| Absent pigment network | 53 | 98.1 |

| Telangiectasia | 18 | 33.4 |

| Background erythema | 17 | 31.5 |

| Perifollicular pigmentation | 12 | 22.2 |

| Reduced pigment network | 9 | 16.7 |

| Marginal pigmentation | 6 | 11.1 |

| White globules | 5 | 9.3 |

| Reverse pigment network | 5 | 9.3 |

| White scales | 2 | 5.6 |

| Brown background | 2 | 3.7 |

| Microkoebnerisation | 15 | 27.7 |

| Leukotrichia | 12 | 22.2 |

| Starburst pattern | 11 | 20.3 |

| Polka dot sign | 6 | 11.1 |

| Zoon’s balanitis (n = 20) | ||

| Dotted vessels | 20 | 100 |

| Reddish orange structureless areas | 19 | 95 |

| Curved vessels | 19 | 95 |

| Looped vessels | 15 | 75 |

| Wavy vessels | 15 | 75 |

| Cayenne pepper appearance | 13 | 65 |

| Red globules | 9 | 45 |

| Straight vessels | 9 | 45 |

| Branched vessels | 7 | 35 |

| Spiral vessels | 5 | 25 |

| Coiled vessels | 1 | 5 |

Psoriasis

Psoriasis involving genitalia was seen in 33 (6%) of cases. Majority 25 (75.8%) were males. Twenty-six (78.8%) patients had extragenital involvement. Scrotum (19, 76%) in males and labia majora (7, 87.5%) in females were commonly involved. On clinical examination, erythematous plaques (28, 84.8%) with scaling (25, 75.8%) were the most common findings [Figure 4a]. On dermoscopy, most lesions showed regularly arranged dotted vessels in 28 (84.8%) over an erythematous background in 32 (97%) with white scales in 27 (81.8%) cases [Figure 4b and Table 2].

- Genital psoriasis presenting with well-defined erythematous plaque over the glans penis.

- Regularly arranged dotted vessels over erythematous background in dermoscopy of genital psoriasis (yellow square).

Lichen simplex chronicus

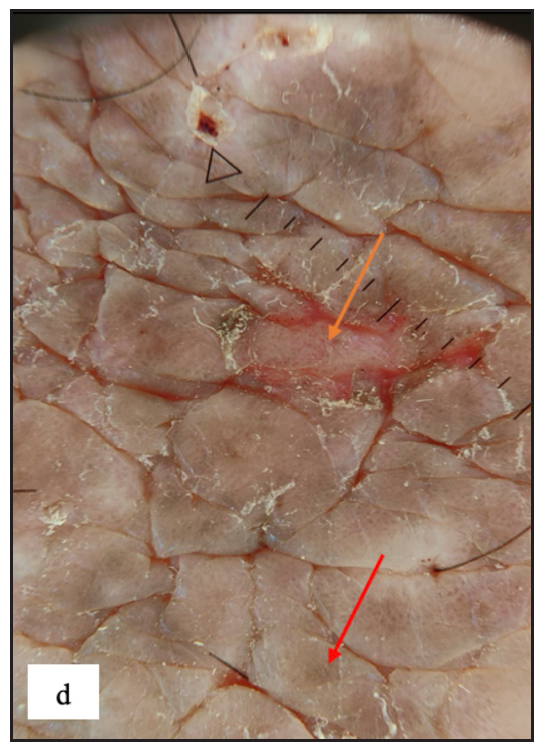

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) was noted in 43 (7.8%) cases. Thirty-three (76.7%) of them were male. Scrotum in males and labia majora in females were the only sites involved Figure 4c]. On dermoscopy, LSC was characterised by exaggerated skin markings in 40 (93%) and white scales in 37 (86%) cases [Figure 4d].

- Lichen simplex chronicus showing massive lichenified plaque over the scrotum.

- Dermoscopy depicting increased rugosity mimicking sulci and gyri along with brown dots (red arrow) and erosion (orange arrow) in lichen simplex chronicus.

Scrotal dermatitis

Twenty-two (4%) patients had scrotal dermatitis. Scrotal dermatitis is typically seen as a disorder comparable to contact dermatitis that occurs elsewhere and is not recognised as a distinct disease entity. Some authors categorise the condition as a distinct disease entity due to its multifactorial aetiology. Scrotal dermatitis is characterised by severe itching, erythema, scaling and lichenification of the scrotal skin. It can be caused by a variety of factors, the most common of which are psychological stress and either allergic or irritant contact dermatitis. Because of the extensive use of antiseptics and over-the-counter topical treatments, this condition is very frequent in modern culture. Persistent scrotal skin inflammation induces the production of numerous inflammatory mediators or proteolytic agents, resulting in pruritus and a vicious itch-scratch cycle that eventually results in an erythematous or lichenified scrotum, sometimes known as a ‘wash leather scrotum’.4 The most common morphology was erythematous plaques seen in 22 (100%) cases followed by scales in 17 (77.3%) cases [Figure 4e]. Background erythema in 16 (72.7%) with white scales in 17 (77.3%)cases were the most common findings seen in dermoscopy. Irregular dotted vessels were seen in 11 (50%) cases [Figure 4f].

- Scrotal dermatitis characterised by ill-defined oozy erythematous plaque with yellowish crusting and scaling over the scrotum.

- Irregularly arranged dotted vessels (white circle) with telangiectasia, background erythema and yellowish-brown scales (black arrow) were noted on dermoscopy of scrotal dermatitis.

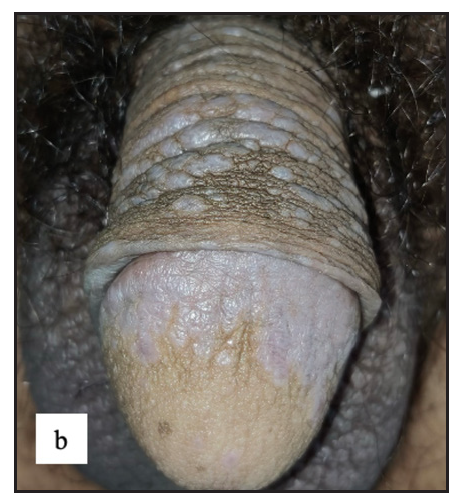

Lichen planus

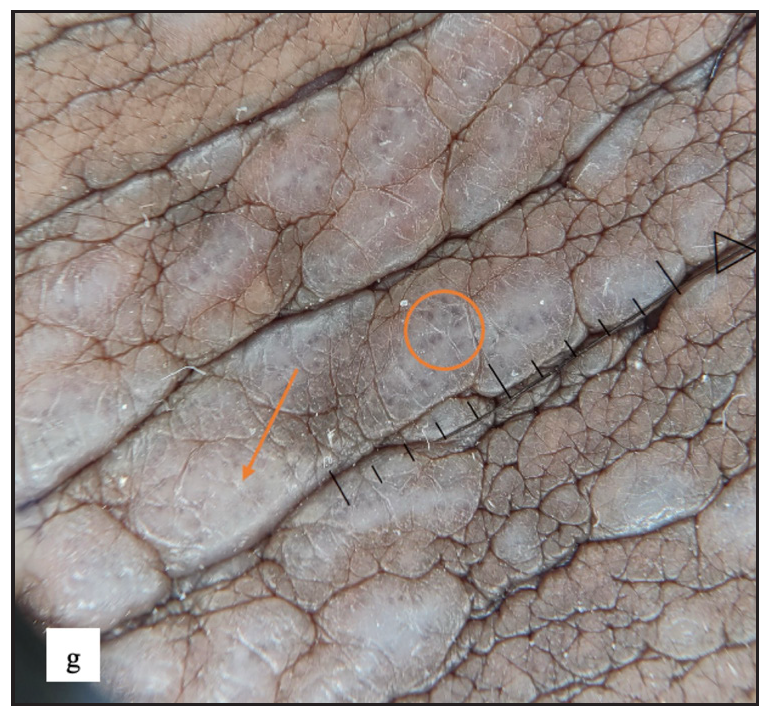

Genital lichen planus was present in 39 (7.1%) of all cases. The majority of patients were men (94.9%). Lesions were present over the penile shaft in 22 (59.4%) and glans penis in 21 (56.7%) males. Violaceous papules were noted in 27 (69.2%), plaques in 10 (25.6%) [Figure 5a and 5b] and hyperpigmented macules in 14 (35.9%) cases. Mostly, papules were round in shape in 31 (79.5%) but annular lichen planus was also found in 10 (25.6%) [Figure 5c] and erosive variant in 2 (5.1%) patients [Figure 5d]. Extragenital lesions were noted in 19 (48.7%) patients. The most common findings noted in dermoscopy were blue-brown dots (31, 79.5%) and purple structureless areas (23, 59%). Wickham striae were noted in 20 (51.3%) cases [Figure 5e, 5f, 5g, and Table 2].

- Various morphologies of genital lichen planus. Multiple well-defined violaceous flat-topped papules were present over the penile shaft in genital lichen planus.

- Well-defined violaceous papuloplaques were present over the penile shaft and glans penis.

- Well-defined annular violaceous plaques with central hyperpigmented macules and atrophy over the glans.

- Erosive lichen planus was found as well-defined erosions with a yellowish crust over a violaceous plaque in the glans penis.

- Dermoscopy showed grey structureless areas with radiating streaks (brown arrow) and brown dots (brown circle).

- On dermoscopy, annular lichen planus were characterised by grey coloured peripheral rim with central brown structureless areas, dots and globules (white arrow).

- Purple structureless areas (orange arrow) with blue-brown dots (orange circle) were noted in dermoscopy.

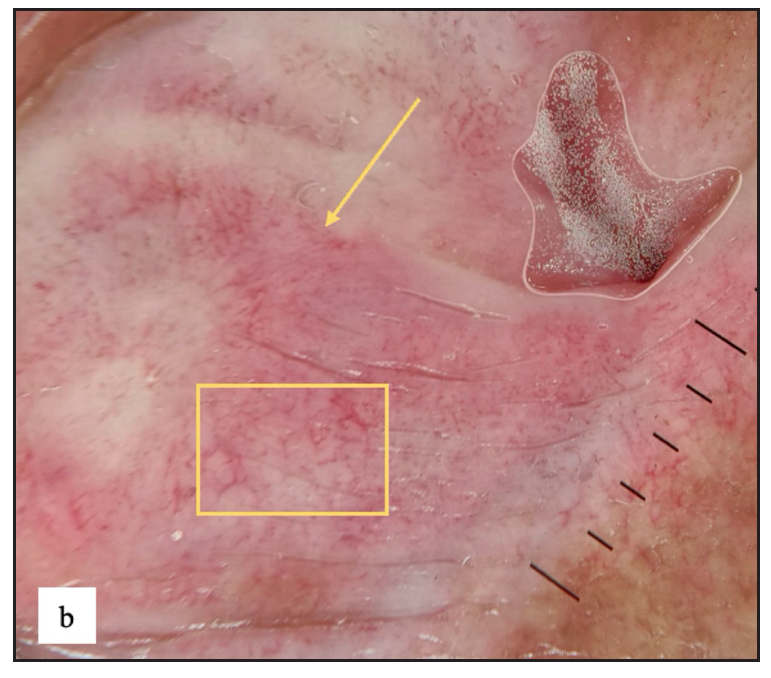

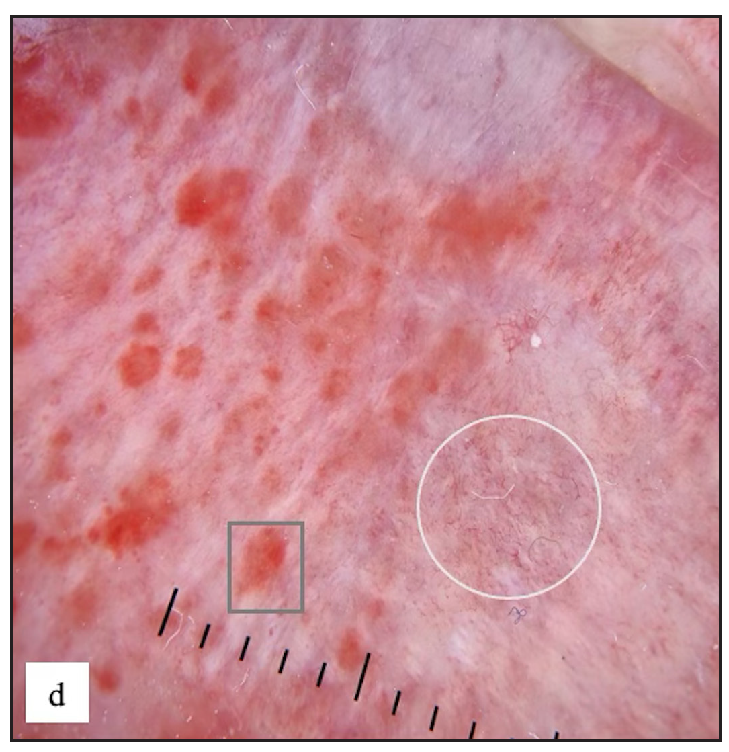

Lichen sclerosus

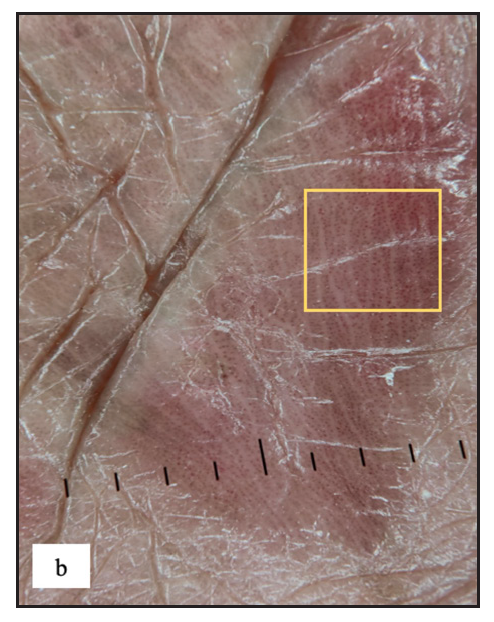

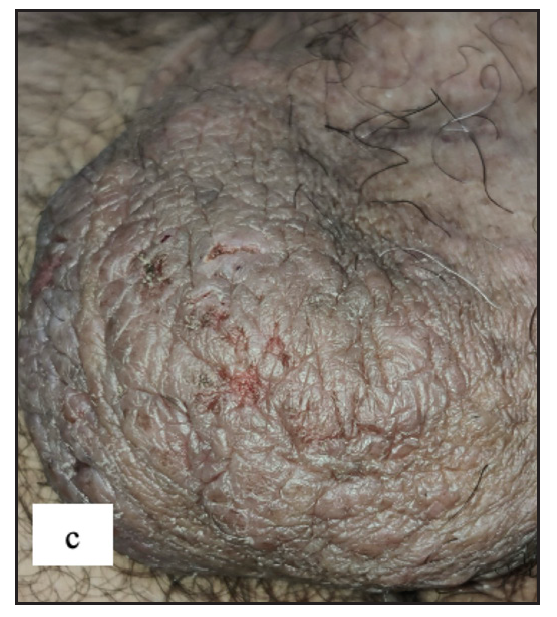

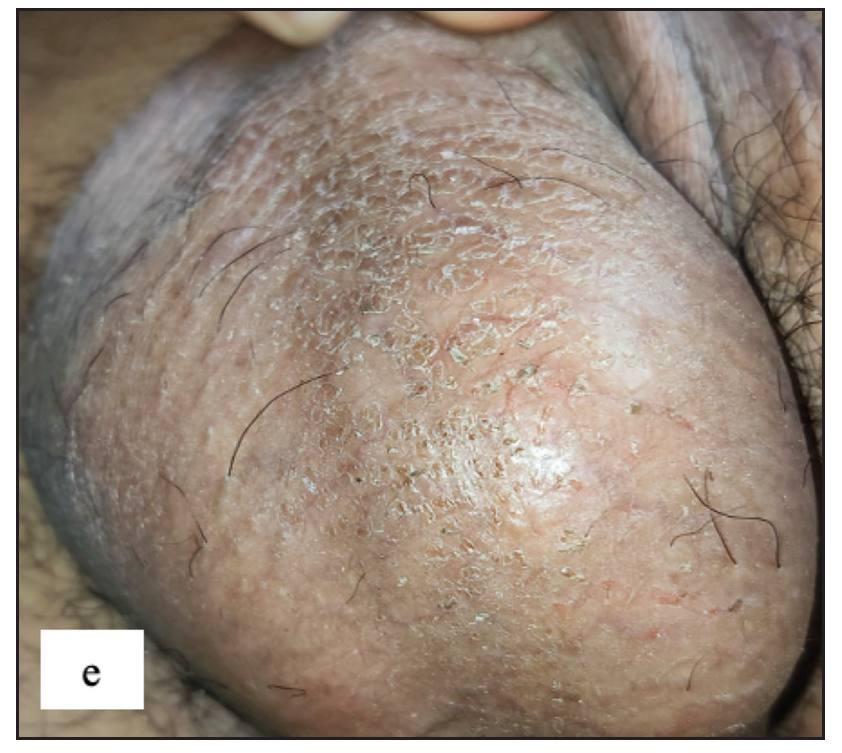

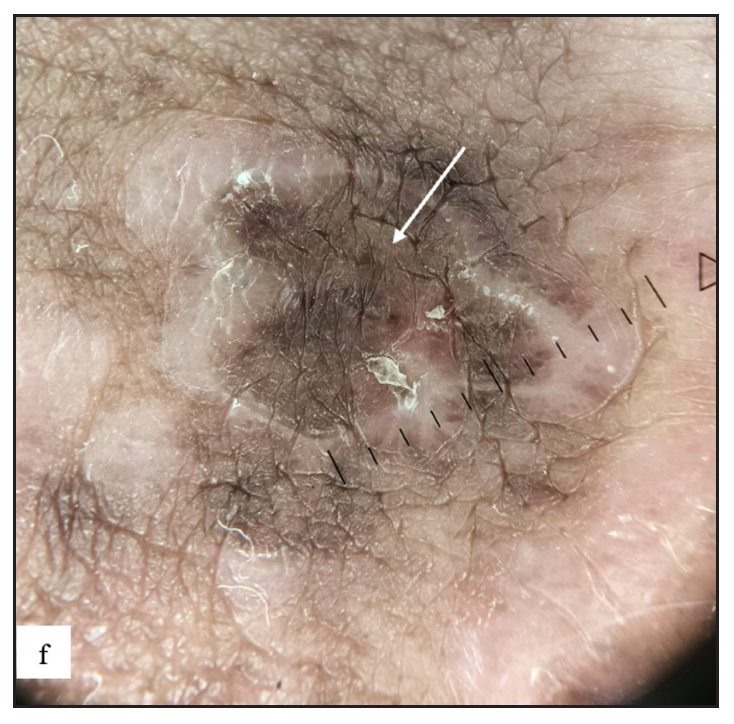

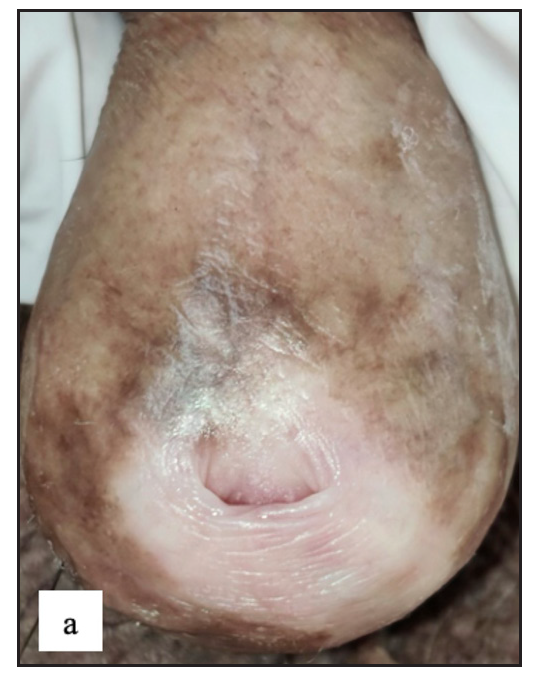

Lichen sclerosus (LS) was identified in 43 (7.8%) of all cases. More than half of those were male (23, 53.5%). The most frequently involved site in males was the prepuce 20 (86.9%) followed by the glans 8 (34.8%). In females the most common sites involved were the labia minora 17 (85%) followed by clitoris and labia majora 16 (80%). Extragenital LS was also found in two (4.7%) cases. The most common morphology found was depigmented plaques in 43 (100%) with atrophy in 39 (90.7%) [Figure 6a]. Induration was found in 27 (64.3%) of cases [Figure 6b and Table 2].

- Lichen sclerosus characterised by a well-defined porcelain white atrophic plaque with a ‘pinhole’ meatus.

- White structureless areas with pinkish background erythema (yellow arrow) and linear, dotted and curved vessels (yellow square) on dermoscopy of lichen sclerosus.

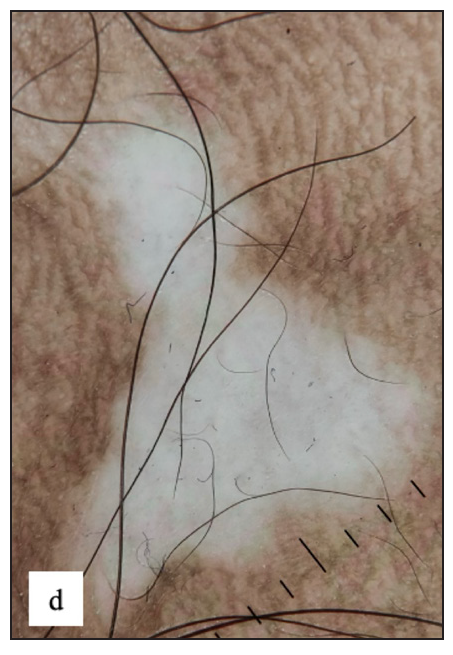

Vitiligo

Fifty-four (9.8%) patients had genital vitiligo and it constituted the second most common disease in this study [Figure 6c]. Around 48 (88.9%) of them were males. Isolated genital involvement was noted in 20 (37%) cases. The most common dermoscopy finding was white structureless areas with absent pigment network in 53 (98.1%) cases, followed by telangiectasia in 18 (33.4%) and background erythema in 17 (31.5%) cases [Figure 6d and Table 2].

- Non-segmental vitiligo presented with multiple well-defined milky white-coloured depigmented macules of varying sizes and shapes over the thighs and penile shaft.

- Genital vitiligo dermoscopy revealed white structureless areas and diffuse white glow with absent pigment network.

Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

Sixteen (2.9%) patients had angiokeratoma. Dusky blue papules were noted mostly over the scrotum [n=13, (92.8%)] in men (n=14) and labia majora [n=2, (100%)] in women (n=2) [Figure 6e]. Dermoscopy showed red lacunae in 14 (87.5%) with a blue-white veil in 11 (68.8%) cases [Figure 6f].

- Multiple discrete dusky blue keratotic papules (red arrow) were present over the scrotum in Angiokeratoma of Fordyce.

- Red lacunae with blue-white veils (yellow arrow) were observed in dermoscopy of Angiokeratoma of fordyce.

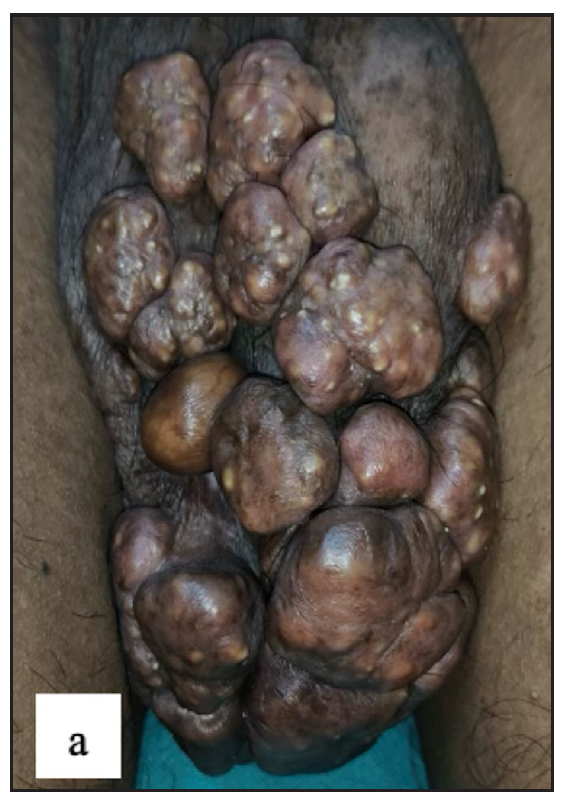

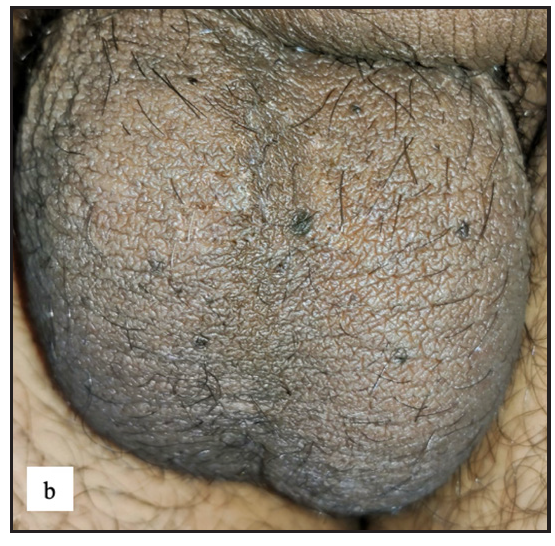

Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis

Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis (ISC) was observed in 27 (4.9%) males. All patients presented with multiple, well-defined firm to hard skin-coloured to yellow nodules of varying sizes over the scrotum [Figure 7a]. On dermoscopy, the most common findings were yellow structureless areas in 27 (100%) with brown peripheral rim in 16(59.3%) cases [Figure 7b].

- Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis showed multiple firm skin-coloured to hyperpigmented swellings with yellowish discolouration over the scrotum.

- Dermoscopy of idiopathic scrotal calcinosis revealed yellow globules and structureless areas (purple arrow), brown dots, peripheral brown areas and blurry vessels

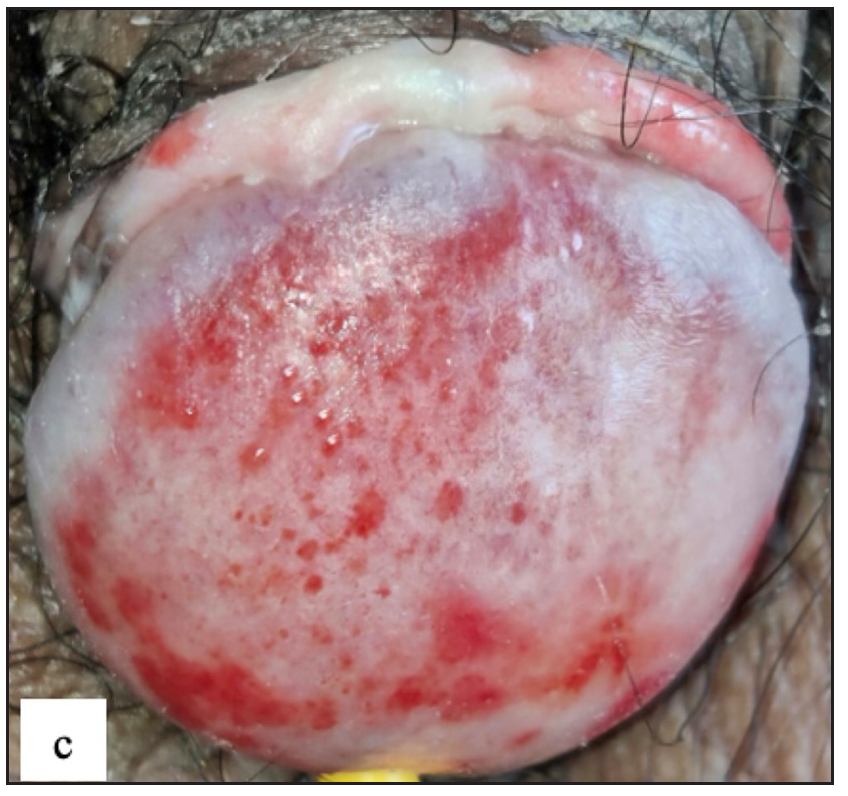

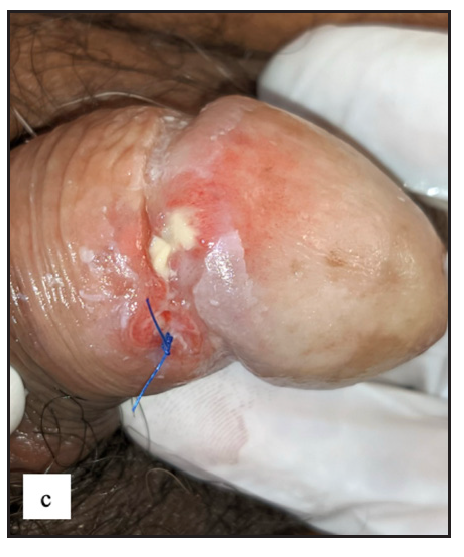

Zoon’s balanitis

Twenty (3.6%) males had Zoon’s balanitis. Asymptomatic, well-defined, glistening moist bright red macules were observed over the glans penis in 19 (95%) cases [Figure 7c]. A cayenne pepper appearance was seen with naked eye examination in nine (45%) and erosions in three (15%) patients. The most common site affected was glans penis in 19 (95%) cases. Dermoscopy showed reddish orange structureless areas in 19 (95%) cases with different types of vascular patterns. Cayenne pepper appearance was noted in 13 (65%) cases [Figure 7d and Table 2].

- Zoon’s balanitis characterised by multiple, well-defined, moist, glistening bright red macules over the glans penis and the prepuce.

- Zoon’s balanitis Dermoscopy showed reddish orange structureless areas, globules (grey square) and dotted, curved, linear and serpentine vessels (white circle).

In our study, we noted that several genital disorders have distinct dermoscopic patterns that may be utilised to distinguish them from one another. LS and genital vitiligo can be separated by a few characteristics. In LS, white structureless areas with pinkish backgrounds and various vascular patterns can be detected, but these are rarely seen in vitiligo (p value <0.001) [Supplementary Table 1]. Between genital psoriasis and scrotal dermatitis, regularly arranged dotted vessels are rather specific to psoriasis (p-value 0.007) [Supplementary Table 2]. Increased rugosity was more commonly seen in LSC (p-value <0.001), whereas diffuse yellow scales (p-value <0.001), perifollicular scales (p-value 0.023) and red structureless areas (p-value 0.009) were more common in scrotal dermatitis [Supplementary Table 3]. Sometimes, genital scabies can mimic LSC, but both can be differentiated using dermoscopy. Increased rugosity over a brown background (p-value <0.001) with diffuse white scales (p-value 0.002) and background erythema (p value <0.001) were mostly seen in LSC and red structureless areas (p-value <0.001), serpiginous tracts or burrows with white patchy and central scales (p-value 0.001), yellow scales (p-value 0.042) and haemorrhagic crusts (p- value <0.001) were seen in genital scabies [Supplementary Table 4]. For dermoscopic comparison between genital scabies and scrotal dermatitis, scabietic nodules were characterised by red structureless areas (p-value <0.001) with dotted vessels (p-value 0.791) and serpiginous tracts (p-value 0.013), central white or yellow scales (p-value 0.001) and haemorrhagic crusts (p-value 0.004). Background erythema with diffuse scales (p-value <0.001) and increased rugosity (p-value <0.001) were seen in scrotal dermatitis [Supplementary Table 5]. Similarly, genital LP can occasionally resemble psoriatic lesions. Psoriasis was more typically found with regularly arranged dotted vessels on an erythematous background (p-value <0.001) [Supplementary Table 6]. Purple structureless areas with blue grey dots and Wickham’s striae were seen only in genital LP (p value <0.001). Lichen nitidus [Figure 7e and 7f] can be differentiated from Fordyce spots by white structureless areas (p value <0.001) with a central brown shadow in lichen nitidus (p value 0.077) [Supplementary Table 7].

- Lichen nitidus typified by multiple discrete shiny hypopigmented pinhead-sized grouped papules over the penile shaft.

- Lichen nitidus dermoscopy revealed white structureless areas with central brown shadow (purple arrow).

Discussion

A total of 503 patients were enrolled in the study. A few patients had more than one dermatosis. So, a total of 550 cases were recruited in the study for final analysis. The prevalence of non-venereal genital dermatoses was found to be 49.1 per 10,000 dermatology outpatients which is much higher than the reported prevalence of 14.1 per 10,000 by Karthikeyan et al.5 and 31.5 per 10,000 by Vinay et al.2,5 It can be attributed to the growing health awareness among the general population and more accessible healthcare facilities. Also, we recruited patients not only visiting dermatology OPD but also referred from urology and gynaecology OPD.

In the current study, the age varied from 4 months to 87 years with a mean age of 34.9 years which is in concordance with previous studies.1,4,6–9 Males (85.3%) outnumbered females by a large proportion (5.8:1) in our study which is also similar to the study of Vinay et al. (males 82.6%)2 because probably women are more hesitant to engage in a conversation related to genital dermatoses due to the social stigma attached.

The number of different non-venereal genital dermatoses detected in this study [Table 1] was 49 which is much larger than that described in all previously published literature where the number of different dermatoses was around 16–25.1,2,5,6

Scabies was the most common disorder (17.6%) followed by vitiligo (9.8%), lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and lichen sclerosus (LS) with 7.8% each. Lichen planus was found in 7.1% of cases. Lichen sclerosus (21.7%), vitiligo (15.8%), lichen simplex chronicus (13.3%) and vulval candidiasis (9.2%) were commonest in a study by Singh et al.7 Saraswat et al. found vitiligo to be more common (18%) followed by pearly penile papules and fixed drug eruptions.1 Scrotal dermatitis and LSC were the most frequent diseases in another report.2

In scabies, the most common morphology was erythematous papules (99%) with excoriations (52.6%). Nodules which are usually found in genitalia were least commonly observed (5.2%) in our study. But, in general, the occurrence of nodular lesions in scabies is less (7%).8,9 Dermoscopic examinations of genital scabies revealed red structureless areas (91.8%) with white scales (63.9%) and dotted vessels (52.6%). Serpiginous tracts were found only in 20.6% cases. Errichetti et al. discovered that non-specific findings such as red structureless areas (100%), dotted vessels (36.7%) and white scales (22.4%) were frequently observed, while specific signs such as ‘jet with contrail’ and serpiginous tract were observed in 24.5% and 34.7%, respectively.10

In lichen simplex chronicus, dermoscopic findings were increased rugosity (93%) with white scales (86%) and background erythema (65.1%), almost similar to features described in the literature.11

The penile shaft in men and labia majora in women were involved most frequently in vitiligo. As per the literature, hair-bearing cutaneous sites like scrotum, and penile shaft in males and perineal and perianal region in females are most often affected.12,13 The most common dermoscopic finding was white structureless areas with absent pigment network (98.1%) along with telangiectasia (33.4%) and background erythema (31.5%). Telangiectasia and erythema can be due to thin genital skin.

In lichen sclerosus (LS), 15–20% of cases can have extragenital manifestations.14 In our study, two cases (4.7%) had extragenital involvement, almost similar to the findings of Kumar et al. (5.4%).15 The most common site affected in males was prepuce and in females, it was labia minora which are similarly described by Singh N. et al. and Kumar et al.7,15Architectural changes, such as phimosis, and atrophy of labia minora and clitoris, were observed in 62.8% cases in our study compared to Singh N et al. who found it only in 19.2% of cases.7 This may be because patients presented late in the disease course and also since some of the cases were from the urology OPD where patients may present with phimoses. On dermoscopy, white structureless areas (100%) with background erythema (81.3%) were the most common finding and various vascular patterns were noted in our study, as detailed by Kamat et al.3

Genital LP rarely manifests as flat-topped violaceous papules. Annular lesions are typically observed across the penile shaft and scrotum. There are also arc-like and streak-like patterns. On the female genitalia, the clinical forms of LP are mostly erosive, papulosquamous and seldom hypertrophic.16 But, the most common morphology in our study was violaceous papules (69.2%). Annular and reticulate variants were found in 25.6% and 10.3%, respectively. Regarding sites, the penile shaft (59.4%) and glans penis (56.7%) were most commonly affected in men and mons pubis and labia (50%) in women. The most common findings noted in dermoscopy were blue-brown dots (79.5%) and purple structureless areas (59%). Wickham’s striae, the most typical finding, was noted only in 51.3% cases. Lacarrubba et al. described genital lichen planus dermoscopy findings as typical, linear pearly whitish structures (Wickham striae) arranged in a reticular, annular, dotted/starry sky or rounded/globular configuration.11

The appearance of genital psoriasis can be difficult to interpret, especially in uncircumcised males, because a mucosal location rather than keratinised skin is affected.17 In our patients, lesions were commonly present over the scrotum (76%) and penile shaft in males (72%) and labia majora in females (87.5%). Erythematous plaques (84.8%) with white scaling (75.8%) and papules (63.6%) were the most frequent finding in genital examination, similar to Meeuwis et al.17 On dermoscopy, regularly arranged dotted vessels (84.8%) over an erythematous background (97%) were seen, as described by Kamat et al.3

Zoon’s balanitis or plasma cell balanitis was found in 3.6% of the study participants in our study which has been noticed in 2%–2.7% of the population in a study by Saraswat et al. and Vinay et al.1,2 The mean age of onset in our population was 41.9±16.9 years which is comparable to the existing literature.18,19 Asymptomatic, glistening, moist bright red macules were observed over the glans penis (95%) which was similar to a study by Chauhan et al.20 The presence of focal or diffuse reddish-orange to rust-coloured structureless areas (95%) as well as vessels of diverse morphologies (100%) were the most prevalent dermoscopic observations identified, comparable to Chauhan et al.20

Pearly penile papules are a frequent occurrence that affects 14.3 to 48% of males.21 They were found in 4.2% of the study subjects in our research which is in contrast to a study by Puri et al. (10%)22 and Saraswat et al. (16%).1 They are commonly confused for warts and misdiagnosed as Tyson’s glands or Fordyce’s ectopic sebaceous glands. Thirty-nine percent of our patients who presented to the OPD with pearly penile papules had venereophobia.

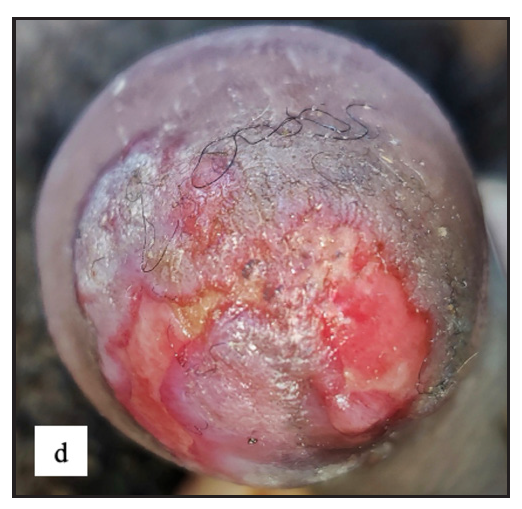

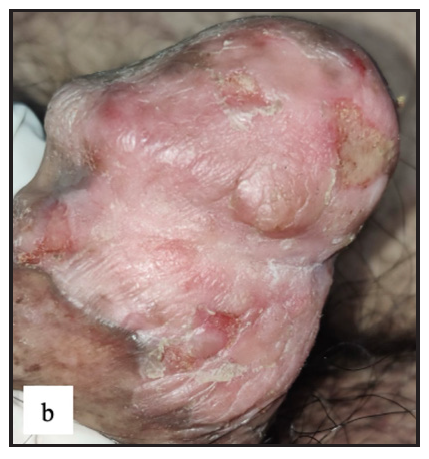

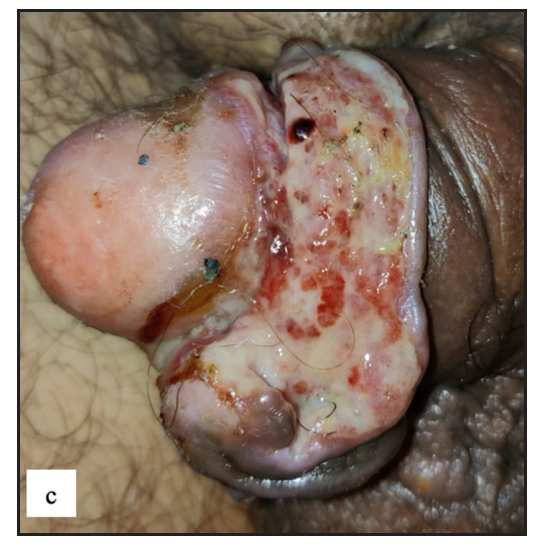

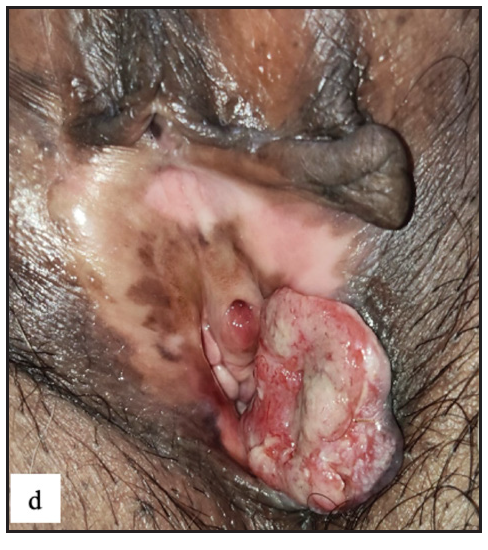

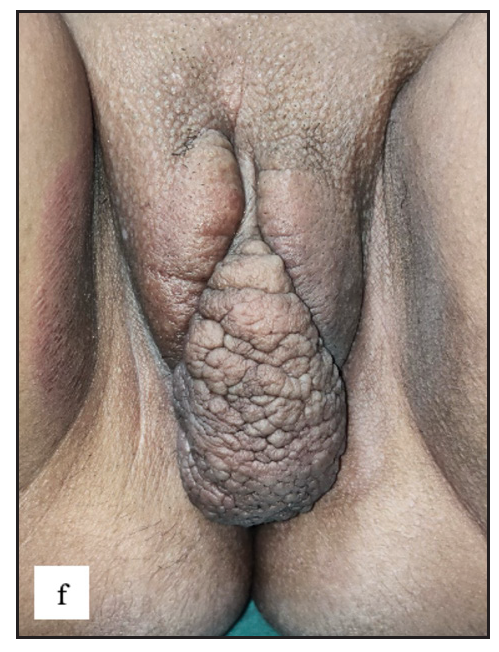

There were two (0.4%) cases with premalignant diseases [Figure 8a and 8b] and three (0.5%) patients having malignancy [Figure 8c, 8d, 8e and 8f]. Previous research found that the prevalence of malignant diseases ranged from 0.1% to 15.7%.2,22,23

- Pseudoepitheliomatous keratotic and micaceous balanitis was seen as whitish yellow hyperkeratosis with underlying whitish pink indurated plaque over glans penis.

- Well-defined erythematous indurated plaque with multiple ulcers and yellowish slough in Bowen’s disease over glans penis.

- Well-defined firm to hard exophytic mass with ulceration, discharge and haemorrhage in coronal sulcus in penile squamous cell carcinoma.

- Round exophytic mass overlying lichen sclerosus in left labia majora in vulval squamous cell carcinoma.

- Left labia majora showing cutaneous metastasis with dystrophic calcification and lymphedema in a case of left CA ovary.

- Dermoscopy of cutaneous metastasis revealed pinkish white structureless areas (blue arrow), yellow scales (green arrow), scattered yellow globules (yellow arrow) and curved vessels (red arrow).

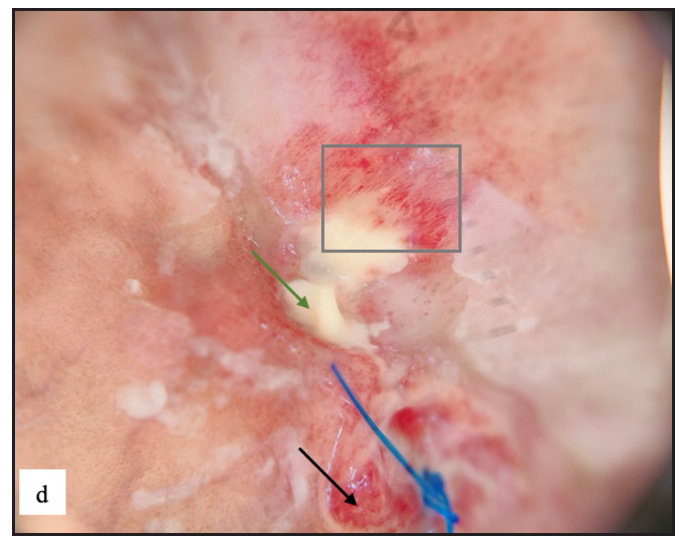

We also diagnosed a few rare cases in this study which are classically not described under non-venereal genital dermatoses in the literature. These included verrucous epidermal naevus [Figure 9a], genital porokeratosis [Figure 9b], penile mucormycosis [Figure 9c, 9d], genital crohn’s disease [Figure 9e] and angiomyxoma of vulva [Figure 9f and 9g].

- Well defined linear hyperpigmented papulo-plaque over left labia majora in verrucous epidermal naevus.

- Multiple discrete hyperpigmented papules with raised keratotic rim over scrotum in genital porokeratosis.

- Indurated painful ulcer with yellowish slough over coronal sulcus in penile mucormycosis.

- Dermoscopy of penile mucormycosis showed red (black arrow) and yellow structureless areas (green arrow) with dotted and linear vessels (grey square).

- Crohn’s disease in the genital area characterised by painful erythematous nodules, abscesses and atrophic scars on the vulva and thighs.

- Single pedunculated firm verrucous mass from left labia majora in vulval angiomyxoma.

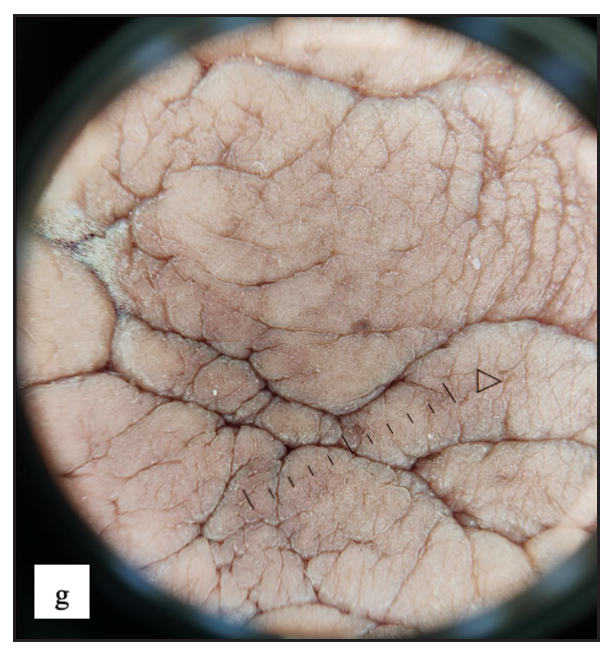

- Increased rugosity mimicking sulci and gyri with brown background was noticed in dermoscopy of vulvar angiomyxoma.

Limitations

Histopathology was not performed in all cases, hence findings of dermoscopy and histopathology could not be correlated. There was also no specific questionnaire regarding the quality of life in non-venereal genital dermatoses and sexual-life-related quality of life.

Conclusion

Non-venereal genital dermatoses are common and more so among males. The present study describes detailed clinical and dermoscopy features of non-venereal genital dermatoses in Indian patients. Dermoscopy is a useful tool in the diagnoses of these diseases. Non-venereal genital dermatoses can have a mild to moderate impact on the quality of life and some patients can suffer from venereophobia. Early diagnosis and treatment would help in the proper management of these patients.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, number AIIMS/IEC/2021/3597, dated 06/09/2021.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- A study of the pattern of nonvenereal genital dermatoses of male attending skin OPD at a tertiary care center. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS.. 2014;35(2):129-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Non-venereal genital dermatoses and their impact on quality of life-A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol.. 2022;88(3):354-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatoscopy of nonvenereal genital dermatoses: A brief review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS.. 2019;40(1):13-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Scrotal dermatitis - Can we consider it as a separate entity? Oman Med J. 2013. ;28(5):302-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non‐venereal dermatoses of male genital region‐prevalence and pattern in a referral centre in South India. Indian J Dermatol.. 2001;46(1):18‐22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non venereal benign dermatoses of vulva in sexually active women: A clinical study. Int J Res Dermatol.. 2016;2(2):25-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of non-venereal dermatoses of female external genitalia in South India. Dermatol Online J.. 2008;14(1):1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodular scabies: A classical case report in an adolescent boy. J Parasit Dis.. 2015;39(3):581-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopy of nodular scabies: An observational study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.. 2023;37(1):e82-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopy of genital diseases: A review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.. 2020;34(10):2198-207.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Male genital vitiligo. Ann Dermatol Venereol.. 2022;149(2):92-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genital vitiligo in children: Factors associated with generalized, non-segmental vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol.. 2020;37(1):64-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of lichen sclerosus in boys and girls: A systematic literature review of epidemiology, symptoms, genetic background, risk factors, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatr Dermatol.. 2022;39(3):400-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Genital lichen planus: An underrecognized entity. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS.. 2019;40(2):105-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Genital psoriasis: A systematic literature review on this hidden skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol.. 2011;91(1):5-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoon balanitis: A comprehensive review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS.. 2016;37(2):129-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Rook’s Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology (Ninth edition). Chichester West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

- Dermoscopic Characterization of Zoon Balanitis: First Case Series from Asia. Indian Dermatol Online J.. 2022;13(1):86-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pearly penile papules: A review. Int J Dermatol.. 2004;43(3):199-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study on non venereal genital dermatoses in north India. Our Dermatol Online.. 2012;3(4):304-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nonvenereal penile dermatoses: A retrospective study. Indian Dermatol Online J.. 2018;9(2):96-100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]