Translate this page into:

Wonder drug for worms: A review of three decades of ivermectin use in dermatology

Correspondence Address:

Saravanan Gowtham

Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Puducherry

India

| How to cite this article: Gowtham S, Karthikeyan K. Wonder drug for worms: A review of three decades of ivermectin use in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019;85:674-678 |

Introduction

Ivermectin has evolved over the last three decades from being a veterinary “blockbuster” drug to a panacea for nematodal infestation and ectoparasitic diseases in humans.[1] This oral drug has breathed fresh life in the management of ectoparasitic infections which was conventionally based only on topical medications. In this review, we discuss the intriguing journey of this drug in dermatology.

History of Ivermectin

In early 1970, Omura and William Campbell identified a soil bacterium which was named Streptomyces avermectinius. The active component produced by the bacterium was termed as avermectin.[2] Ivermectin is a synthetic derivative of avermectin with a structural similarity to macrolide antibiotics.[3] It was first used in veterinary treatment in 1981, and now is being used to treat billions of livestock and pets around the world for varied nematodal infestations.[2] It was first used in humans after 1981 as a treatment against Onchocerca volvulus.[3] The role of ivermectin in dermatology was a serendipitous discovery which catapulted ivermectin to the zenith of anti-parasitic remedies.

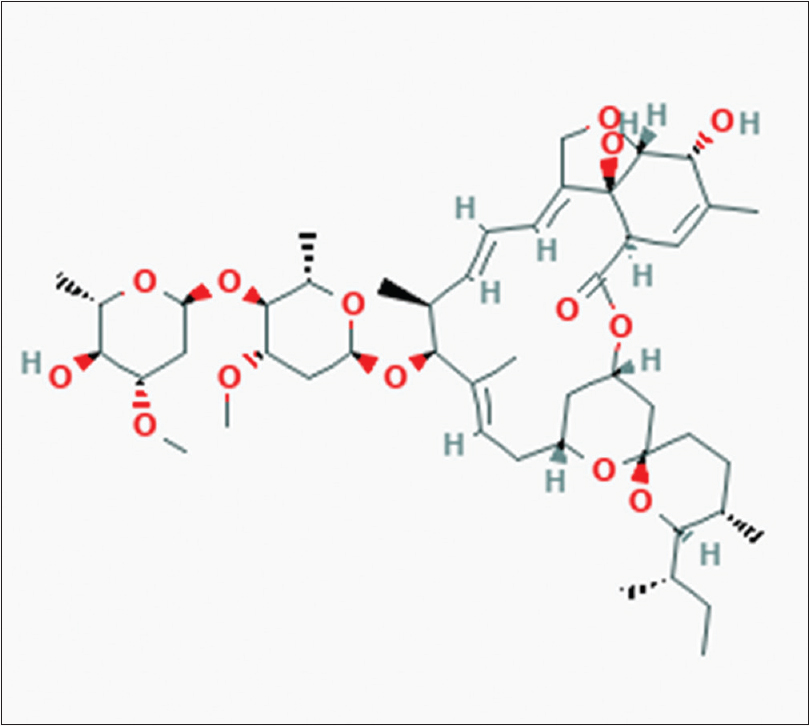

Structure of Ivermectin

The structure of ivermectin is shown in [Figure - 1]. The molecular formula of ivermectin is C48H74O14.[4]

|

| Figure 1: Structure of ivermectin |

Pharmacokinetics

In humans, the oral route is the only approved route for administration of ivermectin, and it is usually recommended to be taken on an empty stomach with water. In the skin, the peak concentration of the drug was noted 8 h after a 12-mg oral dose, whereas the peak serum level is reached in 4 h after administration.[3] Between 6 and 12 h after the dose, a second peak occurs due to enterohepatic recycling of the drug. 5 It is extensively metabolized by cytochrome P450 and is excreted almost exclusively in feces.[3] The half-life of the drug is around 18 h, and the anti-parasitic activity lasts for several months after a single dose.[5]

Mechanism of Action

Ivermectin is an endectocide, which selectively binds to glutamate-gated chloride channels in invertebrates. This causes hyperpolarization of parasite neurons and muscles by increasing chloride ion influx, ultimately resulting in death of the parasite. It acts on endoparasites and ectoparasites by suppressing the nerve impulse conduction in intermediary neurons or in nerve-muscle synapses, respectively.[6],[7] Due to the localization of these channels in the central nervous system and inability of ivermectin to cross the blood–brain barrier, humans are not affected except those with a history of undergoing shunt surgeries. 6

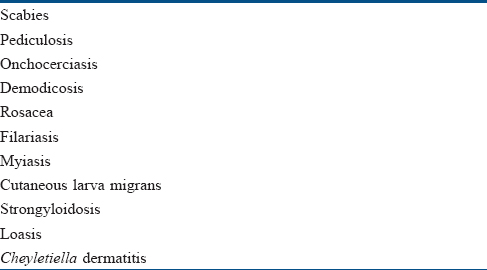

Indications in Dermatology

The indications for ivermectin use in dermatology are summarized in [Table - 1].

Scabies

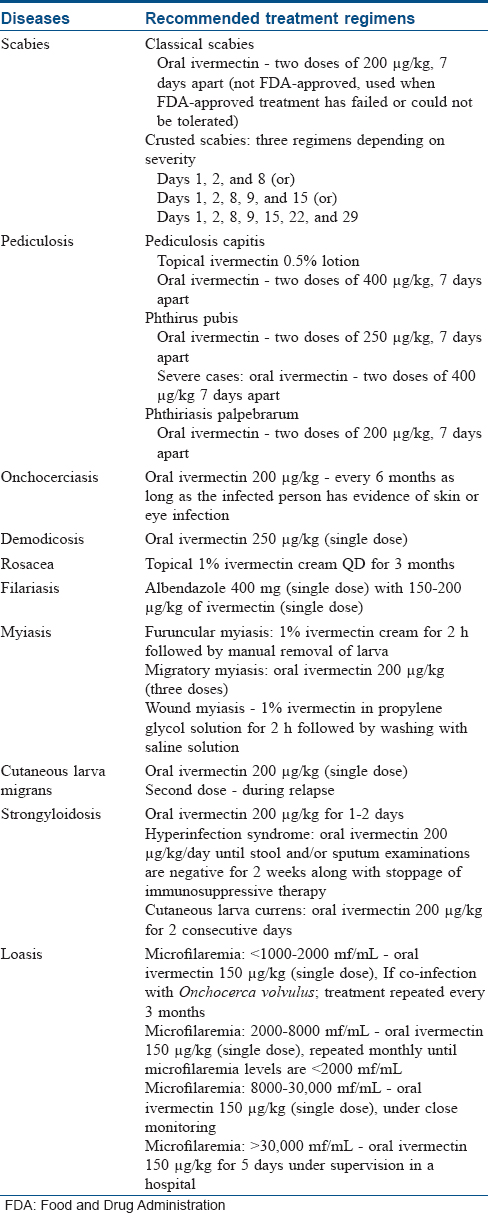

Ivermectin is the only recommended oral medication for scabies.[8] Two doses of oral ivermectin are given 7 days apart, to act on newly hatched scabietic nymph. In severe or resistant cases, it is often combined with topical medications like permethrin.[9] Two doses of topical ivermectin were also found to be as effective as two applications of permethrin.[10] In case of crusted scabies, multiple doses of oral ivermectin are given as shown in [Table - 2].[11]

Pediculosis

Ivermectin lotion (0.5%) is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for the treatment of pediculosis capitis. A single application on dry hair without nit combing is recommended. Oral doses of ivermectin are preferred in difficult-to-treat cases of head lice.[12],[13]

In phthiriasis palpebrarum infestation, oral ivermectin is found to be effective. The adult lice are eradicated in 2 days, but nits disappear gradually.[12]

In phthiris pubis, it is given as 250–400 μg/kg tablets 7 days apart depending on the severity. Topical ivermectin is also effective and a reapplication is recommended every 7–10 days until no live lice is identified for atleast 1 week after treatment.[14]

Demodicosis

Both oral and topical ivermectin are effective in cases of demodicosis.[3] In HIV-associated cases, oral ivermectin is the preferred option.[15]

Rosacea

Ivermectin 1% cream is now approved by US FDA for inflammatory rosacea. Ivermectin not only targets Demodex folliculorum, but also reduces the inflammation associated with the condition.[16]

Cheyletiella dermatitis

Ivermectin is effective in controlling infestations by Cheyletiella species in households having many cats. The dermatitis induced in humans regresses spontaneously within 3 weeks of elimination of the mites. Oral ivermectin can be given to prevent recurrence of the disease in humans.[3]

Myiasis

In case of furuncular myiasis, the treatment goal is complete removal of larva from the skin. It includes the usage of topical ivermectin followed by manual removal. Oral treatment is not recommended as an inflammatory reaction can develop to the dead larva in the skin. In case of migratory myiasis, oral ivermectin will mobilize the parasite to the body surface. Wound myiasis requires manual removal of the larva and debridement of necrotic tissues. Usage of short-contact topical ivermectin can cause reduction of pain in 15 min and death of a majority of the larvae. A single oral dose of ivermectin can facilitate removal of maggots of Hypoderma lineatum by causing spontaneous migration of maggots.[17]

Filariasis

Individuals with filariasis with a positive immunochromatographic test or those with microfilaremia, should be treated with an antifilarial drug. Ivermectin causes rapid disappearance of microfilaria but not the adult worm. The World Health Organization recommends the combination of both albendazole and ivermectin for effective management. Combination with diethylcarbamazine was found to be superior than the individual drugs.[18]

Onchocerciasis

Ivermectin is used to control endemic onchocerciasis. However, it kills only the larva and not the adult. It is given every 6 months as long as there is evidence of skin or eye infection. In case of recurrence, pruritus, rash, or eosinophilia, further doses should be given at 6–12 monthly intervals.[6]

Cutaneous larva migrans

A single oral dose of ivermectin ensures a 77%–100% cure rate. The cure rate increases to 97%–100% after one or two supplementary doses. The progression of tract formation stops in 2 days.[19] A single dose of ivermectin is less effective in case of hookworm folliculitis.[20]

Strongyloidosis

The first-line treatment for both acute and chronic strongyloidosis is oral ivermectin. Two consecutive days of oral ivermectin therapy is found to be more effective in cutaneous larva currens. In case of hyperinfection syndrome, immunosuppressive therapy should be stopped or reduced along with initiation of daily oral ivermectin, until stool and/or sputum examinations are negative for 2 weeks.[6],[21]

Loasis

Ivermectin is used to reduce microfilaremia before the administration of DEC. However, administration of ivermectin may trigger encephalopathy in patients with Loa loa microfilaremia >30,000/mL. It is the preferred treatment when there is possible or confirmed co-infection with Onchocerca volvulus. It not only treats onchocerciasis, but also reduces pruritus and frequency of calabar swelling. DEC is the preferred drug and it is started after reducing the microfilaremia levels to <2000 mf/mL.[22] The treatment for Loa loa depends on the microfilaremia levels as given in [Table - 2].

The dosing schedule of ivermectin for various dermatological conditions is summarized in [Table - 2].

Contraindications

Pregnancy and lactation

The safety of ivermectin in pregnancy and lactation has not been established in humans. It is a pregnancy category C drug.[23]

Children

The safety and efficacy for use in children <15 kg has not been established; hence, it is not recommended for children under 15 kg and less than 5 years of age.[24]

Other Conditions

Ivermectin has to be avoided in those who have a history of seizure disorders and those who have had shunt surgeries in the past.[25]

Combination Therapy and Drug Interactions

Anti-parasitic agents are used in combination in view of increasing incidence of drug resistance. In case of onchocerciasis, the combination of ivermectin and doxycycline is highly effective in reducing microfilaremia levels more than ivermectin monotherapy.[6] In cases of filariasis, albendazole and ivermectin are preferred as they do not modify each other's kinetic behavior.[5]

Antibiotics like doxycycline, erythromycin, or azithromycin have a synergistic effect with ivermectin by increasing its intracellular concentration.[26] Alcohol can increase the plasma levels of ivermectin, whereas orange juice decreases the concentration of ivermectin by inhibiting certain drug transporters.[6]

Adverse Effects

Ivermectin is well-tolerated with minimal adverse reactions, and the degree of adverse events is independent of its concentration.[26],[27] Common adverse events such as constitutional symptoms, pruritus and rash resolve spontaneously or might require symptomatic treatment.[3],[6],[28] A patient can also develop facial edema, headache, and abdominal pain. Rarely, encephalopathy and Steven–Johnson syndrome can develop.[3],[6],[28]

Mazzotti's Reaction

Mazzotti's reaction is an intense inflammatory response to the dead microfilaria, which occurs within 7 days of treatment with oral ivermectin, manifesting as fever and pruritus. The other manifestations may include urticaria, hypotension, tachycardia, tender lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, and abdominal pain. This can be greatly reduced by adding low-dose corticosteroids at the initiation of treatment, without affecting the microfilaricidal activity.[29],[30] A 6-week course of doxycycline preceding ivermectin, reduces the risk of Mazzotti's reaction by causing sterilization of female adult onchocerca.[30],[31]

Toxicity

Ivermectin is considered to be relatively safe with no genotoxicity; but at a very high dose, it has been shown to cause embryotoxicity in animals.[3] The toxicity though rare, can be due to acute or chronic drug over-dose. It can occur at therapeutic dosage only when there is a defect in the ABCA1 gene which causes defect in P-glycoprotein.[32] Ivermectin toxicity manifests as increased salivation, diarrhoea, breathing difficulty, muscle fasciculation, drooping of lips, bilateral mydriasis, depression, ataxia, recumbency, reduced pupillary reflex, absent menace reflex and rarely encephalopathy and death.[30],[33] Clinical signs usually progress during the first 36 h after administration.[33]

Resistance

Resistance to ivermectin has been reported in nematodes of horses, sheep, and other animals after 20 years of use.[3] An increasing trend of tolerance of scabies mite to ivermectin has been noted in endemic areas recently. Resistance is also noted in patients with crusted scabies who require repeated doses of ivermectin. The possible reasons could be the following:

- Mutation in GluCl channel receptors which reduces the sensivity of ivermectin [3]

- Mutation of ABCA1 gene resulting in alteration of P-glycoprotein [3]

- Reduced efficacy of single-dose ivermectin, due to lack of ovicidal action.[3]

Future Perspective

Moxidectin is a macrolide lactone belonging to the Milbemycin subfamily produced by fermentation of Streptomyces cyanogriseus. Its affinity for P-glycoprotein is inferior to ivermectin. The half-life of moxidectin is more than 20 days with higher bioavailability because of its high lipophilicity and better penetration into the hyperkeratotic skin. Moxidectin also has a good safety profile with low resistance.[34]

Conclusion

Ivermectin has revolutionized the management of nematodal and ectoparasitic infection. The drug which spelt the death knell for onchocerciasis also had its impact on the treatment of many ectoparasitic infestations and will continue to do so in the future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Crump A, Ōmura S. Ivermectin, 'wonder drug' from Japan: The human use perspective. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2011;87:13-28.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Discovery of Ivermectin Mectizan – American Chemical Society. Available from: https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/ivermectin-mectizan.html. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 3].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA. Ivermectin: Pharmacology and application in dermatology. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:981-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ivermectin. Pubchem. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6321424. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 17]

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

González Canga A, Sahagún Prieto AM, Diez Liébana MJ, Fernández Martínez N, Sierra Vega M, García Vieitez JJ. The pharmacokinetics and interactions of ivermectin in humans – A mini-review. AAPS J 2008;10:42-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Chhaiya SB, Mehta DS, Kataria BC. Ivermectin: Pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol 2012;1:132-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Chen IS, Kubo Y. Ivermectin and its target molecules: Shared and unique modulation mechanisms of ion channels and receptors by ivermectin. J Physiol 2018;596:1833-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Gunning K, Pippitt K, Kiraly B, Sayler M. Pediculosis and scabies: A treatment update. Int J Clin Pract 2013;24:211-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Panahi Y, Poursaleh Z, Goldust M. The efficacy of topical and oral ivermectin in the treatment of human scabies. Ann Parasitol 2015;61:11-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Chhaiya SB, Patel VJ, Dave JN, Mehta DS, Shah HA. Comparative efficacy and safety of topical permethrin, topical ivermectin, and oral ivermectin in patients of uncomplicated scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:605-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009;75:340-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Sangaré AK, Doumbo OK, Raoult D. Management and treatment of human lice. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:8962685.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, Izri A, Hofmann R, Mann SG, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med 2010;362:896-905.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of pediculosis pubis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:1425-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Rather PA, Hassan I. Human demodex mite: The versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol 2014;59:60-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Siddiqui K, Stein Gold L, Gill J. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ivermectin compared with current topical treatments for the inflammatory lesions of rosacea: A network meta-analysis. Springerplus 2016;5:1151.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012;25:79-105.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Prevention C-C for DC and. CDC – Lymphatic Filariasis – Treatment; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/treatment.html. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 16]

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:252-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Van den Enden E, Stevens A, Van Gompel A. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1246-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Shorman M, Al-Tawfiq JA. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and gram-negative sepsis in a patient with astrocytoma. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:e288-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Boussinesq M. Loiasis: New epidemiologic insights and proposed treatment strategy. J Travel Med 2012;19:140-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Ivermectin.pdf. Available from: http://news.nursesfornurses.com.au/test/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/ivermectin.pdf. [ Last accessed on 2018 Aug 17].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Wilkins AL, Steer AC, Cranswick N, Gwee A. Question 1: Is it safe to use ivermectin in children less than five years of age and weighing less than 15 kg? Arch Dis Child 2018;103:514-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Dang K, Tribble AC. Strategies in infectious disease prevention and management among US-bound refugee children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2014;44:196-207.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Sangaré AK, Rolain JM, Gaudart J, Weber P, Raoult D. Synergistic activity of antibiotics combined with ivermectin to kill body lice. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016;47:217-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Boussinesq M, Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Chippaux JP. Clinical picture, epidemiology and outcome of loa-associated serious adverse events related to mass ivermectin treatment of onchocerciasis in Cameroon. Filaria J 2003;2(Suppl. 1):S4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Oyibo WA, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF. Adverse reactions following annual ivermectin treatment of onchocerciasis in Nigeria. Int J Infect Dis 2003;7:156-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Stingl P, Pierce PF, Connor DH, Gibson DW, Straessle T, Ross MA, et al. Does dexamethasone suppress the Mazzotti reaction in patients with onchocerciasis? Acta Trop 1988;45:77-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Henson PM, Mackenzie CD, Spector WG. Inflammatory reactions in onchocerciasis: A report on current knowledge and recommendations for further study. Bull World Health Organ 1979;57:667-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Tamarozzi F, Halliday A, Gentil K, Hoerauf A, Pearlman E, Taylor MJ. Onchocerciasis: The role of wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts in parasite biology, disease pathogenesis, and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:459-68.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Edwards G. Ivermectin: Does P-glycoprotein play a role in neurotoxicity? Filaria J 2003;2 Suppl 1:S8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Chandler RE. Serious neurological adverse events after ivermectin-do they occur beyond the indication of onchocerciasis? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;98:382-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Gopinath H, Aishwarya M, Karthikeyan K. Tackling scabies: Novel agents for a neglected disease. Int J Dermatol 2018;57:1293-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

74,573

PDF downloads

4,883