Translate this page into:

Plica polonica: from national plague to death of the disease in the nineteenth-century Vilnius

2 Faculty of History, Vilnius University, Lithuania

Correspondence Address:

Eglė Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė

Center for Neurology, Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos, Santariškių Street 2, Vilnius - 08661

Lithuania

| How to cite this article: Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė E, Jatužis D, Kaubrys S. Plica polonica: from national plague to death of the disease in the nineteenth-century Vilnius. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84:510-514 |

Introduction

“Plica polonica is an endemic disease of Poland, Tartary, and neighboring countries; it begins with a long-lasting nervous-rheumatic ailment and progresses to the formation of uncombed and filthy hair plaits in hairy parts of the body, especially the head,” wrote Joseph Frank (1771–1842), Professor of Special Therapy and Clinical Medicine at Vilnius University in 1815.[1]Plica polonica, a tuft ofmatted, felted and filthy hair, is a phenomenon that was often considered an affliction exclusively characteristic of Poland and Lithuania; however, a number of publications on plica came mostly from central European regions.[2],[3]

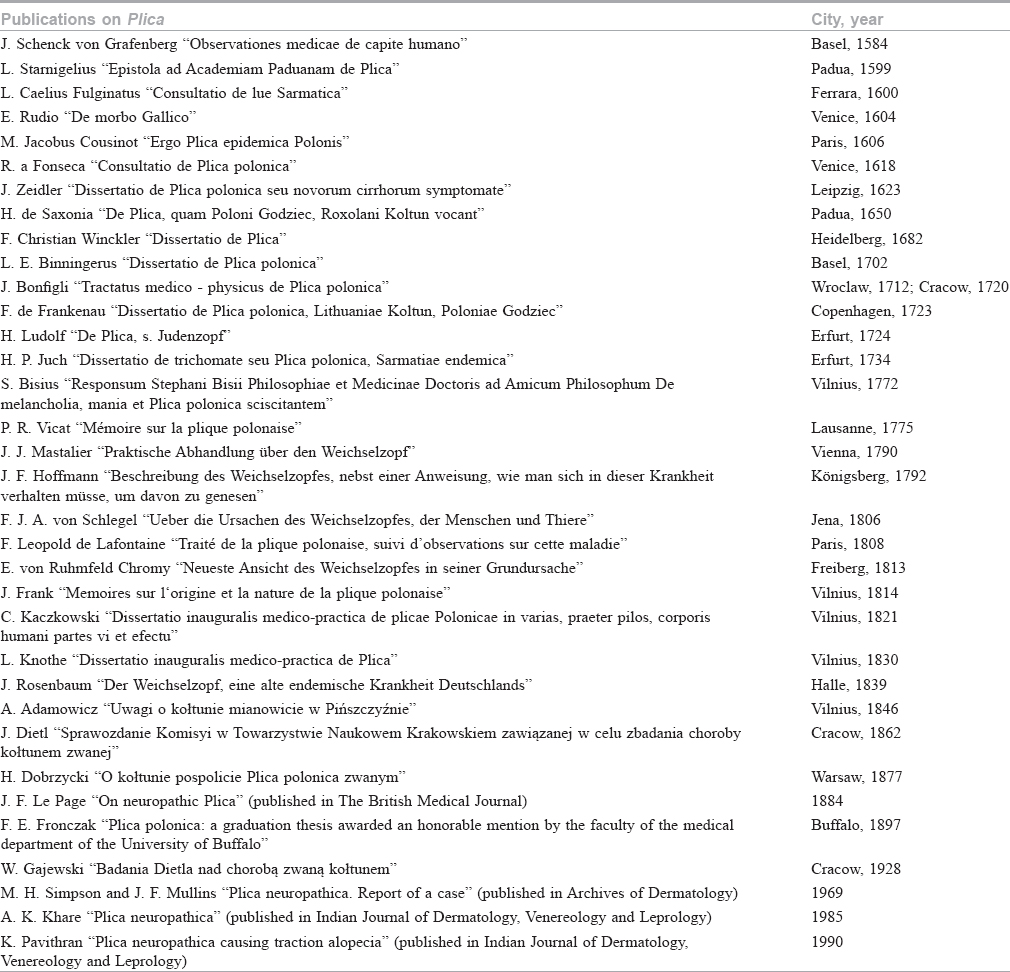

Approximately, 900 articles on plica polonica were published up to the nineteenth century.[4],[5] Johannes Schenck von Grafenberg was probably the first who mentioned the phenomenon of plica polonica in his “Observationes medicae de capite humano” (Basel, 1584), followed by Laurentius Starnigelius, who described plica in “Epistola ad Academiam Paduanam de plica” (Padua, 1599).[5],[6] In the Baroque epoch, various treatises on plica polonica came from Basel, Paris, Venice, Leipzig, Hamburg and other European cities.[1],[5] During the eighteenth century, publications on plica were also produced in central European regions, that included the cities of Erfurt, Halle, Cracow, Vienna, Königsberg and many other places.[1],[5] Almost all authors emphasized devastating signs and symptoms of plica such as irreversible plaiting of the hair accompanied by lice, headache, mutilating arthritis, scoliosis and onychogryphosis.[5],[6]

Plica polonica (also called plica polonica judaica, trichoma, lues sarmatica in Latin, kołtki, goźdźiec, kołtun in Polish, kaltūnas in Lithuanian, la plique polonaise in French, weichselzopf, judenzopf, hexenzopf in German)[1] had been thought to be the effect of a spell cast by a witch, suggesting that occurrences of plica were caused by a supernatural influence,[4],[7] a punishment from God, a disease, which could not be simply disposed of by cutting off one's hair, as this would incur serious complications and even a patient's death.[3],[8],[9] Moreover, plica was believed to break the patient, causing ulcerations, apoplexy, seizures, headaches, insomnia, blindness, deafness and a myriad of other aches and diseases.[4],[10] This was because the disease was assumed to circulate in the blood and thus exist throughout the body.[4] Later, in the second half of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, the medical professionals started to criticize the existence of the disease concluding that plica is not a disease, and there are no complications after cutting the plait [Table - 1].[4]

The first scientific publication on plica polonica in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was written by Stephanus Bisius (Stephanus Bisio; 1724–1790), a lecturer of anatomy and physiology at Vilnius University. In his book, Responsum Stephani Bisii Philosophiae et Medicinae Doctoris ad Amicum Philosophum De Melancholia, Mania et Plica Polonica sciscitantem (“A Reply of the Doctor of Philosophy and Medicine Stephanus Bisius to the Question from the Philosophical Society About Melancholia, Mania and Plica Polonica”), written in Latin and Polish, and published in 1772 in Vilnius, the author criticized attempts to associate medicine with metaphysical speculations.[3],[11] “Plica is not a disease, but a human error, derived from negligence and superstitions, nourished by old women's deceit and obscurity, strengthened by the unreasonable credulity of priests” – wrote Bisius.[11] However, the questions of whether plica polonica is a disease and, if so, what causes it and how it can be treated have been frequently asked.[3]

Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine descriptions of plica polonica, assess the evolution of the perception of this phenomenon from national plague to a nonexistent disease in case reports, doctoral theses and treatises published by scholars from the “endemic” region for the condition at Vilnius University and Vilnius Medical Society in the nineteenth century.

Methods

We first analyzed case reports, presented by Joseph Frank in his Mémoires Biographiques de Jean-Pierre Frank et de Joseph Frank son fils (“Biographical Memoirs of Johann Peter Frank and his Son Joseph Frank”), written in French during 1803–1823.[12] Then we turned to two doctoral theses written in Latin and defended in Vilnius University—Dissertatio inauguralis medico-practica de plicae Polonicae in varias, praeter pilos, corporis humani partes vi et efectu (“Medical-Practical Inaugural Thesis on the Effects of Plica Polonicafor the Various Parts of the Human Body”) by Carolus Kaczkowski, published in 1821,[13] and Dissertatio inauguralis medico-practica de plica (“Medical-Practical Inaugural Thesis on Plica”) by Ludovicus Knothe, defended in 1830.[7] Lastly, we analyzed the descriptions of plica polonica in the treatise O kołtunie pospolicie “plica polonica” zwanym (“On Plait, Commonly Called Plica Polonica”), written in Polish by Henryk Dobrzycki and published in 1877.[5]

Results and Discussion

A national plague

Joseph Frank was a graduate of the University of Pavia (1785–1791), Extraordinary Professor of Special Therapy at his Alma Mater (1795) and Chief Physician at the General Hospital of Vienna (1796–1802).[12] In 1803, both Joseph Frank and his father Professor Johann Peter Frank (1745–1821) were invited to Vilnius University (which was one of the oldest universities in Central and Eastern Europe, founded in 1579) by the Rector, where Joseph spent almost 20 years.[14] One of the most important areas of his interest in Vilnius was the investigation of the curious disease plica polonica.[15]

Plica polonica, called “a national plague, a result of chronic contagions and local conditions”, was discussed as a unique disease in his Mémoires.[12] The disease, according to Frank, “is disastrous for the current population; furthermore, it will harm future generations.”[12] Frank assumed that plica involves not only the hair but also other parts of the body. Carcinomatous ulcers erode the patient's skin, bones decay, noses bend, eyes and ears begin to fear light and sounds, insomnia lasts for months, exacerbating patients' torments, and “finally, convulsions begin, a patient becomes delirious,” several years pass and death comes, with rare exceptions.[12] Frank presented his patients who suffered from this condition.

In 1815, he described Countess Josephine Przedziacka, a young, gallant and divorced lady, who arrived in Vilnius and became completely exhausted. “I was sure that it was plica and tried to promote entanglement of the hair (…). Plica was formed and thus her sufferings reduced and she even gained some weight.”[12] Although the patient was happy about her recovery, she complained of not being able to arrange her hair. “The Countess begged me to cut off her plica. I strictly forbade it while the plica had not been fully spread and separated.”[12] However, the Countess returned to Minsk and “one doctor gave her more pleasant advice. The plica was cut off, and the woman soon died.”[12] The Professor reasoned that plica polonica could be associated with malignancy: “Crowds [of patients] came up to me. Many of them had carcinomatous ulcers, and I began to suspect that plica and cancer are associated.” He said further, “Madame Groddek developed a stomach tumor, which was probably caused by the spread plica.”[12]

Cutting immature plica was supposed to cause health deterioration and even patients' death, as reported by Joseph Frank. How can this paradox be explained? As previously suggested in the literature, ordinary folk as well as some physicians believed that plica was not only a representation of a general illness but also a tangible counterpart to any hidden disease.[4] Therefore, physicians recommended entanglement of plica to cure various ailments and warned about the relapse of disease if a patient decided to cut off an immature plait. Thus, Joseph Frank, an emissary of enlightened medicine at Vilnius University, assumed that plica polonica is a disease involving patients' skin, hair, nervous system and various internal organs. He believed it was a national plague and encouraged eradication of this “disease” in the region of Poland and Lithuania.

Both a diseaseand a treatment method

Another physician and master of medicine Carolus Kaczkowski (Karol Maciej Kaczkowski; 1797–1867) was also interested in the phenomenon of plica polonica. Kaczkowski was a graduate of Vilnius University, worked at the Vilnius Therapy Clinic with Professor Joseph Frank and practiced medicine among the poor in Vilnius.[16] In the doctoral thesis on plica polonica, published in 1821 in Vilnius, the author depicted a splendid clinical picture of the phenomenon. Kaczkowski described plica manifestations and associated this condition with number of pathologies: diseases of the skin, bones, tendons, muscles, blood vessels, the heart, lungs, reproductive and nervous systems.[13]

Plica, as described in detail by Kaczkowski, was associated with various integumentary and nervous system diseases.[13] The author noted that patients often complained of specific smell of their sweat, uncombed hair plaits in the scalp and other body parts (armpit, groin, chest), and of rough, bent and nodulated nails. Patients with plica were often diagnosed with impetigo, erysipelas and carcinomatous ulcers. Furthermore, they complained of headaches, experienced vertigo and epileptic seizures. Syncopes, sleep disorders, diseases of the spinal cord and paralysis were also diagnosed. Patients complained of hallucinations and experienced melancholy, mania and hypochondria.[13]

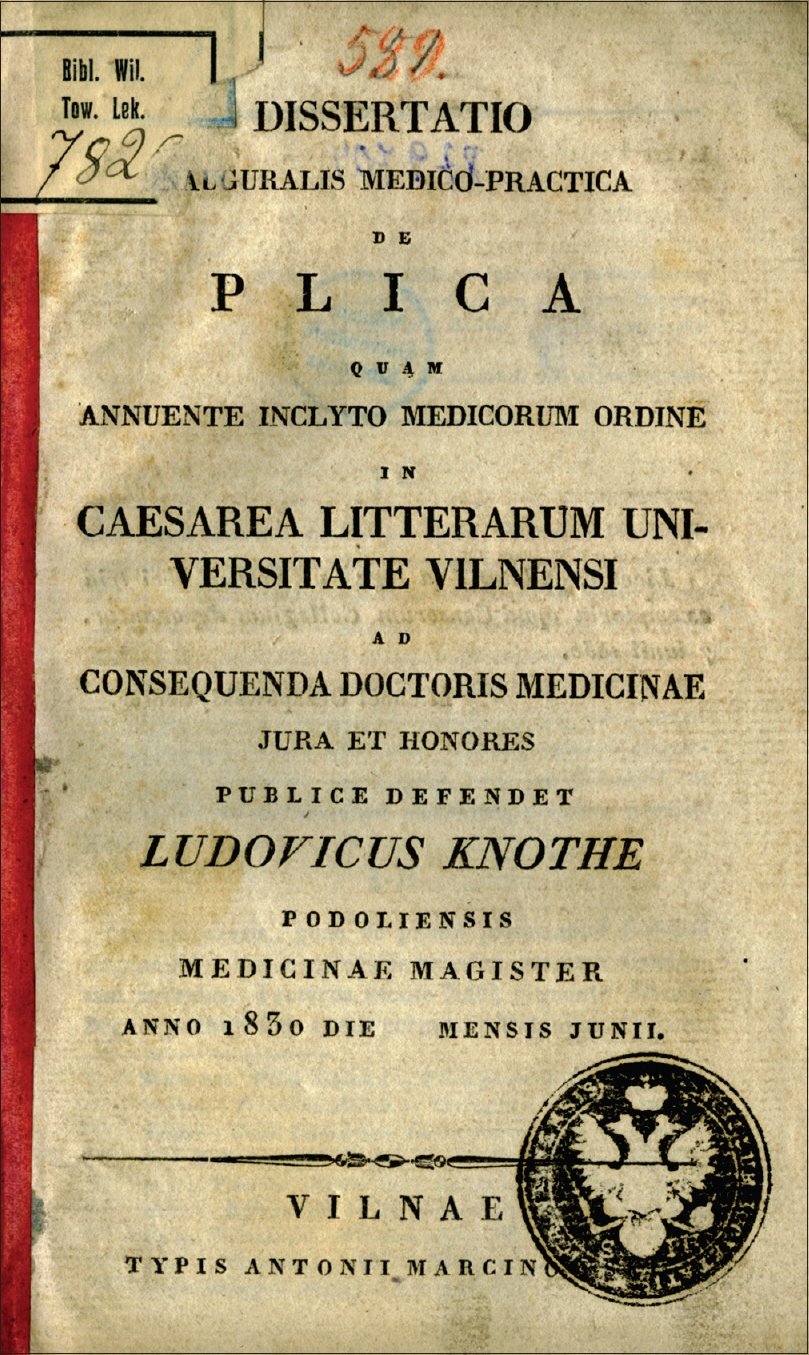

Nine years after Kaczkowski's thesis, master of medicine Ludovicus Knothe, who was also a graduate of Vilnius University, published another doctoral thesis on plica polonica in Vilnius [Figure - 1]. The author described predisposing factors and causes that had a major influence on the development of plica polonica.[7] For example, individuals from certain age groups (maturity, senescence) were considered to be prone to plica entanglement. Further, patients from some social classes (villagers, beggars) and Jews were believed to have a higher chance of developing plica polonica. Unhealthy environmental conditions (swampy or flooded lands, contact with sulfur vapors and metals) were believed to provoke plica. Sadness, anxiety, resentment and horror were assumed to predispose patients to plica polonica. Knothe also discussed whether plica was a contagious or congenital disease and disputed plica's association with syphilis, leprosy, arthritis and lymphatic system diseases.[7]

|

| Figure 1: The title page of L. Knothe's doctoral thesis, published in 1830 in Vilnius. Vilnius University library, Rare book department. With permission from Vilnius University library |

To avoid or eliminate plica, Knothe firstly recommended building a special hospital for patients suffering from the disease, prohibiting marriages among the affected, improving living conditions of servants, prohibiting persons with plica from entering public bathhouses, forbidding the sale of old clothes etc.[7] Knothe stated that firstly the cause of plica should be treated; secondly, doctors should promote entanglement of plica, especially in the scalp region; and lastly the mature plica could be cut off. “Cleanness is very important: simple baths or baths with sulfur or potassium [salts] should be recommended,” advised the author. However, “various eye diseases, limb contractures, urinary retention, even madness occur if plica is cut off too early,” he warned.[7] Knothe noted that mercury preparations are “very efficacious” for treating ulcers, impetigo, chronic inflammations and nervous diseases related to plica polonica. Lastly, mature plica (almost naturally separated from the scalp when signs of new hair growth are seen) can be cut off without any harm to the patient.[7]

Thus, plica polonica was believed to be both a disease (as a separate entity) and a treatment method in two doctoral theses defended in Vilnius University in the first half of the nineteenth century. Knothe's suggestions for prophylaxis show that plica polonica was believed to be both a contagious and congenital disease. Plica was also assumed to be associated with malignancy. Although Knothe stated that individuals from certain age groups and social classes had a higher chance of developing plica, this phenomenon was generally believed to affect patients of various ages, social classes and both genders. There were numerous diseases included in the diagnosis of plica polonica, such as impetigo, erysipelas, ulcerations, headaches, epilepsy and even mental disorders. Therefore, we can assume that additional and more careful studies of plica polonica cases can provide valuable information about the morbidity of some integumentary, nervous and mental diseases up to the second half of the nineteenth century in Europe.

Death of the disease

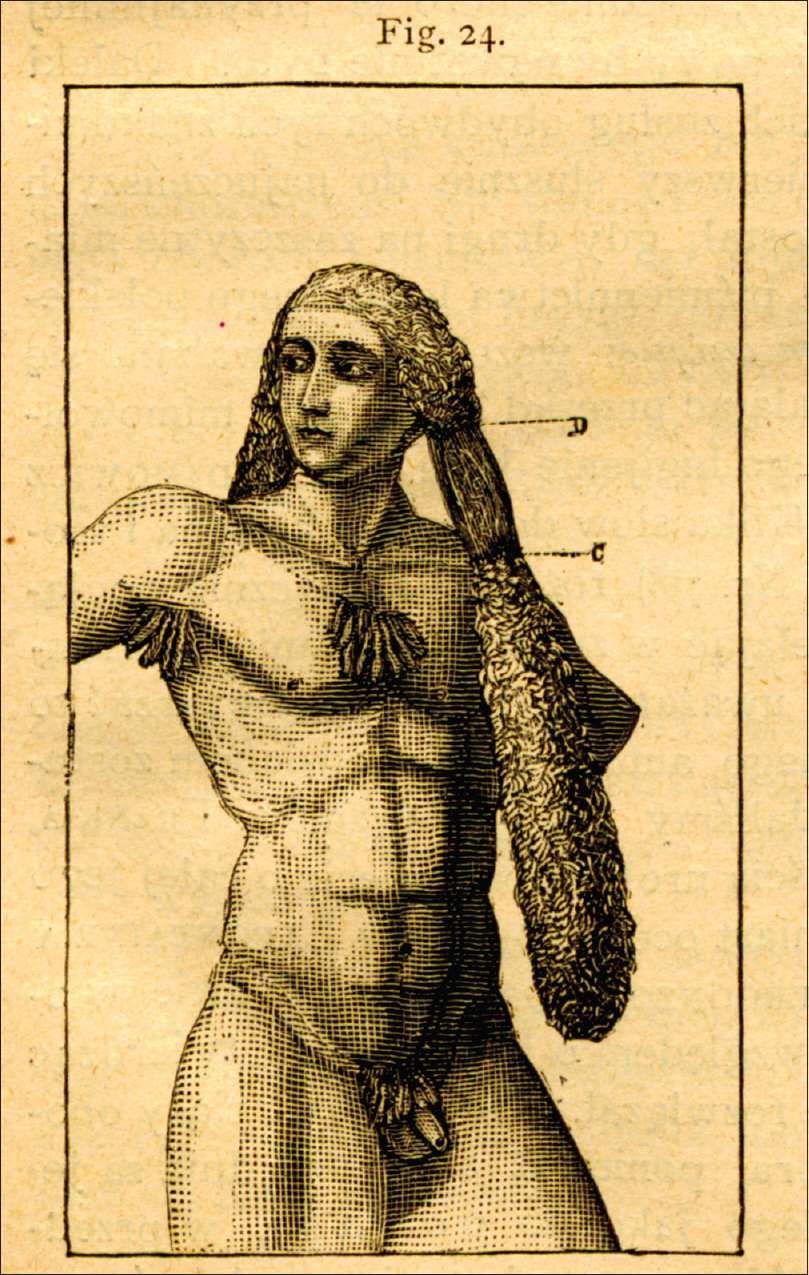

Another famous physician Henryk Dobrzycki (1843–1914) was a graduate of Surgical Medical Academy in Warsaw [16] and the author of the treatise “On plait, commonly called plica polonica,” which was written in Polish in 1876 and published the next year in Warsaw.[5] Dobrzycki performed an analysis of the literature and demonstrated that plica polonica [Figure - 2] is not a disease but a result of “obscurity, prejudice and lack of hygiene.”[5]

|

| Figure 2: Depiction of plica polonica in H. Dobrzycki's tractate, published in 1877 in Warsaw. Vilnius University library, Rare book department. With permission from Vilnius University library |

Dobrzycki stated, “Plica polonica is not a disease per se,” furthermore, this “disease” could be found where prejudice, obscurity and dirtiness flourish. According to the author, “Civilization and plica polonica cannot coexist.”[5] Dobrzycki regretted that some physicians and patients still believed that certain diseases could not be treated without entanglement of plica. Therefore, patients did not seek professional medical treatment, and many who could be cured died because of this ridiculous superstition. Therefore, according to the author, every physician must cut off plica polonica and clearly explain to a patient that plica is not a disease.[5] Dobrzycki participated in a contest organized by Vilnius Medical Society and in 1876 received an award for the best treatise on plica polonica. Eventually, the question of whether plica is a disease was finally closed in Vilnius.[17]

Thus, the perception of plica polonica [Figure - 3] in the nineteenth-century Vilnius evolved from a national plague, an endemic nervous-rheumatic disease, to a nonexistentailment, a result of obscurity and prejudice. However, in some publications by Dobrzycki's contemporaries, plica polonica was still perceived as a disease that severely affected the human body. Plica polonica was called “a disease of the most remarkable kind,”[18] “an affection of the hairy scalp, endemic in Poland, Russia and Tartary,”[19] “the most horrible, incurable” disease, “rendering its victim an object as hideous to behold as the lepers of the East.”[20]Plica polonica was also described as a term “applied to a peculiar matted, felted condition of the hair observed chiefly among Poles”[21] and entitled as “the unsightly disease of matted hair.”[22] However, in other publications, plica polonica was described as a result of the lack of cleanliness combined with pediculosis.[23],[24],[25],[26]

|

| Figure 3: Plica polonica. Museum of the History of Lithuanian Medicine and Pharmacy. With permission from Museum of the History of Lithuanian Medicine and Pharmacy |

In many cultures, hair plays an important role in the development of social constructs about the body. Hairstyles convey powerful messages about a person's beliefs, morality, gender roles, sexual orientation and even religion, political views and socioeconomic status.[27] The symbolic power of the human hair could be traced back from Biblical times: Samson, mentioned in the Book of Judges, had superhuman abilities to kill a lion, to slay an entire army or to destroy a temple with his bare hands; however, after his hair was cut off, Samson's powers were gone and he was imprisoned by the enemies.[28] Cutting one's hair by force symbolizes a defeat, humiliation or punishment. In Nazi Germany, forced cutting of hair represented government's control of Jews.[27]

This historical study has some limitations. We analyzed the perception of plica only in the small European region and during a brief period of time, focusing on Vilnius University and Vilnius Medical Society in the nineteenth century. Therefore, our findings cannot generalize the situation in the other regions. However, it is worth remembering that even though hair is a biological phenomenon, it also has social, religious and personal meanings.

Conclusion

Until the end of the nineteenth century in Vilnius and most probably in other European cities plica polonica was believed to be a multiorgan disease, involving the skin and its appendages and associated with a number of chronic diseases. However, today we cannot find plica polonica in International Classification of Diseases-10, and the phenomenon of plica could be explained by lack of hygiene, pediculosis, pyoderma and other conditions.[29],[30],[31],[32]

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aistis Žalnora and Anna Žurawska for their assistance in translating H. Dobrzycki's texts and several biographical essays from Polish.

| 1. |

Frank J. Praxeos medicae universae praecepta, Partis primae, Volumen secundum. Lipsiae: sumptibus Bibliopolii Kuehnian; 1815.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Slonimskis S. [INSIDE:1] [Materials on the History of Medicine in Lithuania]. Tauta ir žodis 1928;5:540–41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Klajumaitė V. The phenomenon of Plica polonica in Lithuania: A clash of religious and scientific mentalities. Acta Balt Hist Philosophiae Sci 2013;1:53-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Pruszynski J, Putz J, Cianciara D. Plica neuropathica – A short history and description of a particular case. Hygeia Public Health 2013;48:481-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Dobrzycki H. O kołtunie pospolicie “plica polonica” zwanym. Warszawa: w drukarni Emila Skiwskiego; 1877.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Kantor J. Plica polonica: Confusion, confabulation, and the death of a disease. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:633.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Knothe L. Dissertatio inauguralis medico-practica de plica. Vilnae: typis Antonii Marcinowski; 1830.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė E, Žalnora A. The phenomenon of plica polonica in the XVIII th–XIX th centuries in Vilnius. Laboratorinė medicina 2017;2:136-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Budrys V, Račiūnaitė T. The field of the miracle and neurology: Neurological disorders in the miracle books of the Great Duchy of Lithuania. Neurologijos Seminarai 2007;11:39-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Frank J. Praxeos medicae universae praecepta, Partis secundae, Volumen primum, Sectio prima. Lipsiae: sumptibus Bibliopolii Kuehnian; 1818.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Bisius S. Responsum St. Bisii ad amicum philosophum De melancholia, mania et plica polonica. Vilnae; 1772.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Frank J. Mémoires Biographiques de Jean-Pierre Frank et de Joseph Frank son fils, rédigés par ce dernier. Leipzic; 1848.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Kaczkowski C. Dissertatio inauguralis medico-practica de plicae Polonicae in varias, praeter pilos, corporis humani partes vi et efectu. Vilnae: typis Josephi Zawadzki Universit. typographi; 1821.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Kondratas RA. Joseph Frank (1771–1842) and the Development of Clinical Medicine. A Study of the Transformation of Medical Thought and Practice at the End of the Eighteenth and the Beginning of the Nineteenth Centuries. PhD Thesis. Harvard University, Massachusetts; 1977.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė E, Jatužis D. Nervous system disorders and mental diseases presented in “Memoirs” by Joseph Frank. Neurologijos Seminarai 2015;19:296-307.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Polski słownik biograficzny, Tom XI. Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków: Skład narodowy imienia Ossolińskich Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk; 1965.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Triponienė D. Prie Vilniaus medicinos draugijos versmės. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla; 2012.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Beigel H. The Human Hair: Its Structure, Growth Diseases and Their Treatment. London: Henry Reinshaw; 1869.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Hartshorne H. Essentials of the Principles and Practice of Medicine. A Handbook for Students and Practitioners. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea's Son & Co.; 1881.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Anonym. Plica polonica (News Items). Saint Louis Med Surg J 1882;43:562.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Wolff B. Practical Dermatology. A Condensed Manual of Diseases of the Skin; Designed for the Use of Students and Practitioners of Medicine. Chicago: Cleveland Press; 1906.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Garrison F. An Introduction to the History of Medicine with Medical Chronology, Bibliographic Data and Test Questions. Philadelphia, London: W. B. Saunders Company; 1913.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Bristowe J. A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Medicine. London: Smith, Elder & Co.; 1884.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Jackson GT. A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Hair and Scalp. New York: E. B. Treat and Company; 1898.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Fronczak F. Plica polonica. Saint Louis Med Surg J 1897;73:297-313.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Fronczak F. Plica polonica. Saint Louis Med Surg J 1898;74:9-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Pergament D. It's not just hair: Historical and cultural considerations for an emerging technology. Chic Kent Law Rev 1999;75:41-59.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Judges 16:11-22. The Holy Bible. New International Version. International Bible Society; 1984.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Version 2016. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 12].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Simpson MH, Mullins JF. Plica neuropathica. Report of a case. Arch Dermatol1969;100:457-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Khare AK. Plica neuropathica. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1985;51:178-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Pavithran K. Plica neuropathica causing traction alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1990;56:141-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,771

PDF downloads

2,879