Translate this page into:

Urocytological evaluation of pemphigus patients on long term cyclophosphamide therapy: A cross sectional study

2 Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

3 Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

4 Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Sujay Khandpur

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 029

India

| How to cite this article: Khandpur S, Singh S, Mallick S, Sharma VK, Iyer V, Seth A, Kumawat M. Urocytological evaluation of pemphigus patients on long term cyclophosphamide therapy: A cross sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:667-672 |

Abstract

Background: Cyclophosphamide therapy is associated with several urological complications including urinary bladder malignancy. Data on urologic complications of chronic cyclophosphamide therapy for dermatologic conditions is not available.Objectives: To study the urocytological profile of pemphigus patients on long-term cyclophosphamide therapy.

Materials and Methods: In a cross-sectional study, consecutive patients who had received cyclophosphamide therapy for pemphigus for more than 12 months were included. All patients were subjected to urinalysis including microscopy, culture, and urine cytology. Immunocytochemical staining for cytokeratin 20 (CK-20) on urine sediments and ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) for nuclear membrane protein-22 (NMP-22) were performed in all cases. In patients with urinary symptoms, microscopic hematuria, or those detected with abnormal urine sediment cytology, NMP-22, and CK-20 positivity, cystoscopy, and other relevant investigations were also done.

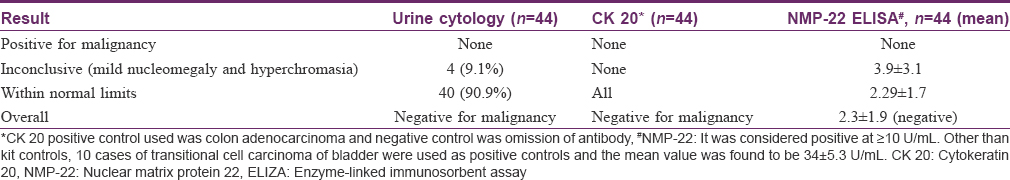

Results: A total of 44 patients (43 of pemphigus vulgaris and one of pemphigus foliaceus) were recruited. Mean duration of cyclophosphamide intake was 2.9 ± 1.7 years (range 1–8 years) with a mean cumulative dose of 53 ± 28.4 g (range 6.5–141 g). Twenty-one cases (47.7%) each were asymptomatic and symptomatic with episodic urinary symptoms [of which two had urinary tract infection (UTI)] and two patients had gross hematuria. Urine cytology revealed mild urothelial nucleomegaly with hyperchromasia in four patients. However, CK-20 and NMP-22 were negative in all samples. Cystoscopy was performed in 21 cases and did not reveal any sign of bladder malignancy.

Limitations: A relatively small sample size and lack of long-term follow-up were limitations.

Conclusions: In our study, no serious urologic complications were found in pemphigus cases on chronic cyclophosphamide therapy.

Introduction

Cyclophosphamide is a cell cycle nonspecific cytotoxic agent. It is a widely used antineoplastic agent and in dermatology practice, it is commonly used as an immunosuppressive and a steroid “sparing” agent in several conditions including inflammatory and sclerosing disorders.

The metabolites of cyclophosphamide are responsible for urological adverse effects which range from lower urinary tract symptoms to the more serious side effects of hemorrhagic cystitis and bladder cancer.[1],[2],[3] Incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis in patients on cyclophosphamide therapy for various indications has varied from 3% to 50% and that of bladder cancer is between 0% and 8% (odds ratio 3.6 to 100).[4],[5],[6] These side effects are known to be a function of the total cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide and hence have been more commonly reported with continuous daily oral dosing than with intermittent intravenous pulse schedules.[2],[4],[7]

Pemphigus is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disease which runs a chronic course and systemic steroids are the mainstay of treatment. Cyclophosphamide has been effectively used for the past five decades, both as daily oral therapy and in intravenous pulse forms. Long-term cyclophosphamide therapy is required to achieve disease control and as maintenance therapy, which often extends beyond 1 year. Data on long-term urological toxicity of cyclophosphamide is primarily available from rheumatology and oncology literature.[4],[8],[9] Because dosing as well as the duration of cyclophosphamide therapy in rheumatological disorders is similar to that in pemphigus, the risk of urological adverse effects also appears to be considerable in pemphigus patients. In view of absence of such data in dermatology literature, we undertook this study.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional prospective, clinical, and laboratory investigational study in pemphigus patients who were on long-term cyclophosphamide therapy prescribed from the Department of Dermatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Patients

Proven pemphigus patients who were on cyclophosphamide therapy in any form for ≥1 year and were willing to undergo all investigations as per protocol were recruited both from dermatology outpatient and inpatient departments at the AIIMS, New Delhi.

Clinical evaluation

It included details about demographic profile, cyclophosphamide therapy received (indication, regimen, duration of treatment, mode of administration, concomitant use of mesna, and total cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide), other urological risk factors (smoking, analgesic abuse, pelvic irradiation, occupational hydrocarbon exposure, and urolithiasis/renal disease), any other significant past medical/surgical history and any urinary symptoms (hematuria, dysuria/burning sensation, frequency, urgency, nocturia, and incontinence). A thorough clinical examination was undertaken which included general physical, dermatological, systemic, and genitourinary examination.

Laboratory evaluation

All patients were subjected to the following investigations: Urine routine and microscopy for 3 consecutive days, urine culture and sensitivity, and cytological study of urine sediment. Urine samples for routine testing and culture were obtained using standard procedure. For urine cytology, patient was asked to drink sufficient water to void twice before the urine sample was collected on the third occasion in a 100-mL beaker.

Microscopic hematuria was defined as ≥3 RBCs/HPF (red blood cells per high power field) on microscopic evaluation of centrifuged sample from two of three properly collected urinalysis specimens. In case of hematuria (either microscopic or gross), following additional investigations were undertaken: Hemogram including platelet count, coagulation profile, renal and liver function tests, serum electrolytes, x-ray of the kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) and ultrasound whole abdomen and pelvis. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of pelvis and abdomen was done if the ultrasonography (USG) showed any suspicious mass/abnormality.

Urine culture was labelled positive for bacteria only if a growth of >105 organisms/mL was obtained. All patients found to be positive on culture were given adequate antibiotic therapy and their repeat urine culture/sensitivity and cytology were performed.

Voided urine for cytology was further subjected to the following three tests in each patient:

Urine routine cytology

Cytospin smears were prepared (Sakura Teck, Tokyo, Japan) and they were evaluated independently by two cytologists experienced in uropathology. Cytology was scored as positive (if any atypical or malignant cells were identified), inconclusive (mild nuclear changes), or negative.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry for CK-20 (1:200) (IgG1 mouse monoclonal antibody, Spring Bioscience) was done. Sections of colon adenocarcinoma were used as positive controls and negative control was obtained by omitting the primary antibody.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP-22) was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a standard NMP-22 Test Kit (supplied by CUSABIO, Hubei Province, China). The range of detection of the assay was 0.1–40 ng/mL. Positive control was urine sample collected preoperatively from 10 histologically proven patients with transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of urinary bladder.

Cystoscopy was done in patients with urinary symptoms, hematuria (microscopic/gross) or if the voided urine cytology/immunocytochemistry/ELISA showed any abnormal findings.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as number and percentage or mean ± standard deviation (mean ± S.D) or median and range as appropriate.

Results

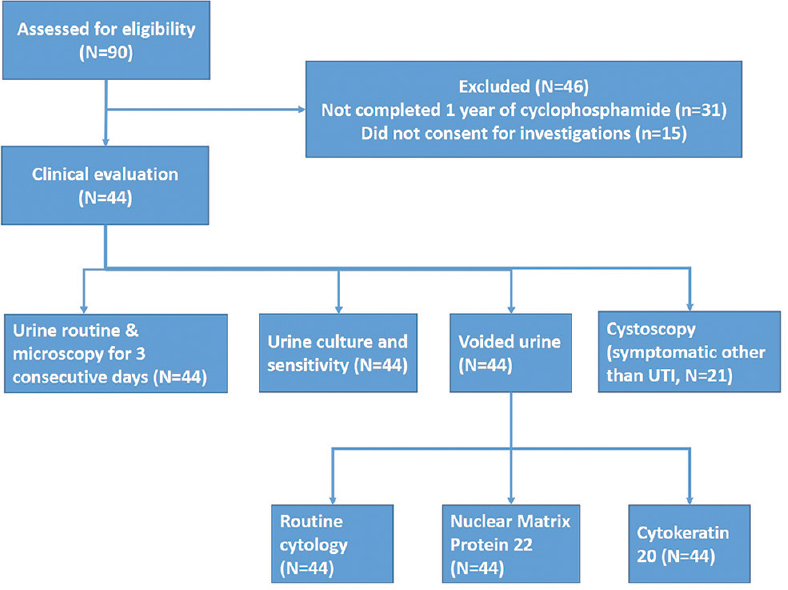

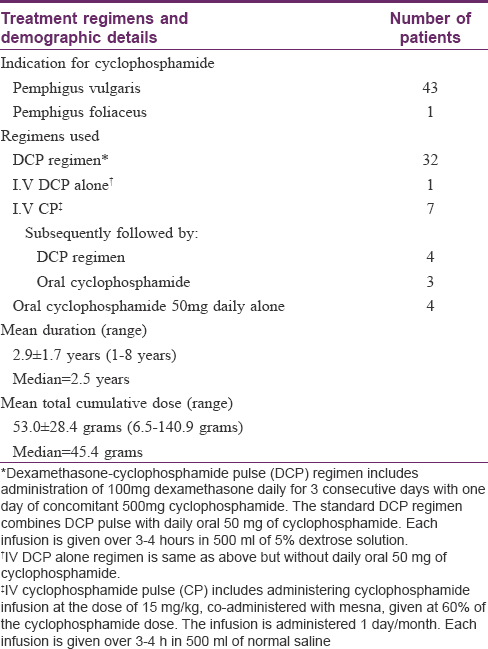

The study plan has been depicted in [Figure - 1]. A total of 44 patients (43 of pemphigus vulgaris and one of pemphigus foliaceus) which included 16 men and 28 women, with a mean age of 46.6 ± 10.7 years were clinically evaluated and underwent all investigations. Cyclophosphamide therapy schedules undertaken by our patients are summarized in [Table - 1]. The duration of cyclophosphamide therapy ranged from 1–8 years (mean 2.95 ± 1.7 years) and the total cumulative dose varied from 6.5 g to 141 g (mean 53 ± 28.4 g). Overall, 32 patients received dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse (DCP) regimen, cyclophosphamide pulse (CP) was received by seven (followed by DCP in four and oral cyclophosphamide in three), oral cyclophosphamide by four, and I.V DCP alone by one patient.

|

| Figure 1: Study flow chart (UTI: Urinary tract infection) |

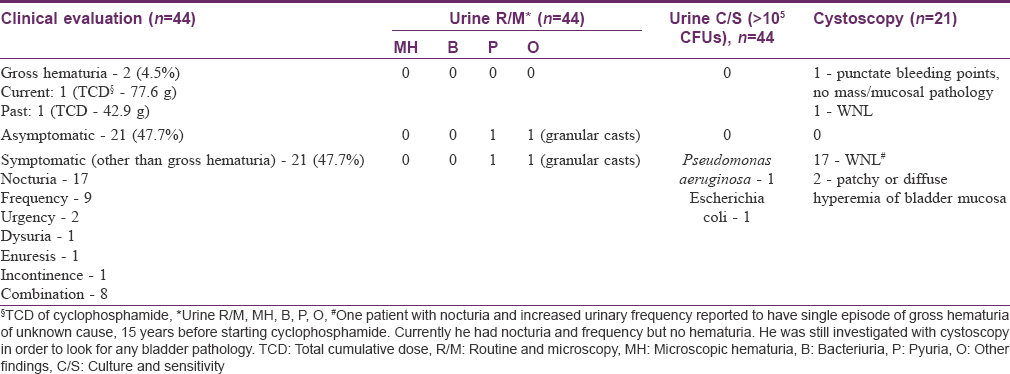

Findings of urological evaluation are depicted in [Table - 2]. Of 44 patients, 21 (47.7%) were asymptomatic, another 21 complained of urinary symptoms except hematuria, and two cases had gross hematuria. Of 21 symptomatic cases, two were detected with urinary tract infection (UTI) and in 19 cases, urinary symptoms appeared after initiation of cyclophosphamide therapy (after variable period of months to years), persisted or improved despite continuing cyclophosphamide, and no other cause was found on history, examination, or urinary investigations. The symptoms were variable in frequency in different patients (ranging from multiple daily episodes in few patients to few episodes over several years in others). Cyclophosphamide was being continued in all these patients during the study period for controlling pemphigus activity. Three of the 21 symptomatic patients were diabetic, but the urinary symptoms started only after initiation of cyclophosphamide therapy.

Of the two cases who had history of gross hematuria, one had six episodes over 3 months, each lasting 3–5 days, after 3.5 years of various cyclophosphamide regimens [12 I.V CPs, daily oral 50 mg cyclophosphamide and DCP regimen (14 DCPs); cumulative dose 77.6 g]. Investigations revealed anemia (Hb — 8.9 gm%, macrocytic), leukopenia (total count — 3400/mL), deranged differential count (N19 L60 E11 M9), and deranged prothrombin time (13.4, control — 12). Biochemical tests were normal. Her x-ray and USG KUB were within normal limits. Cystoscopy revealed only punctate bleeding points with telangiectatic areas without any mass or growth. Six months after stopping cyclophosphamide therapy, all the investigations became normal. The other patient had a single episode of hematuria lasting 4–5 days after 1.5 years of stopping DCP (received 22 pulses; cumulative dose 42.9 g). He had no other urinary complaints. His hematological and radiological investigations and cystoscopy were normal.

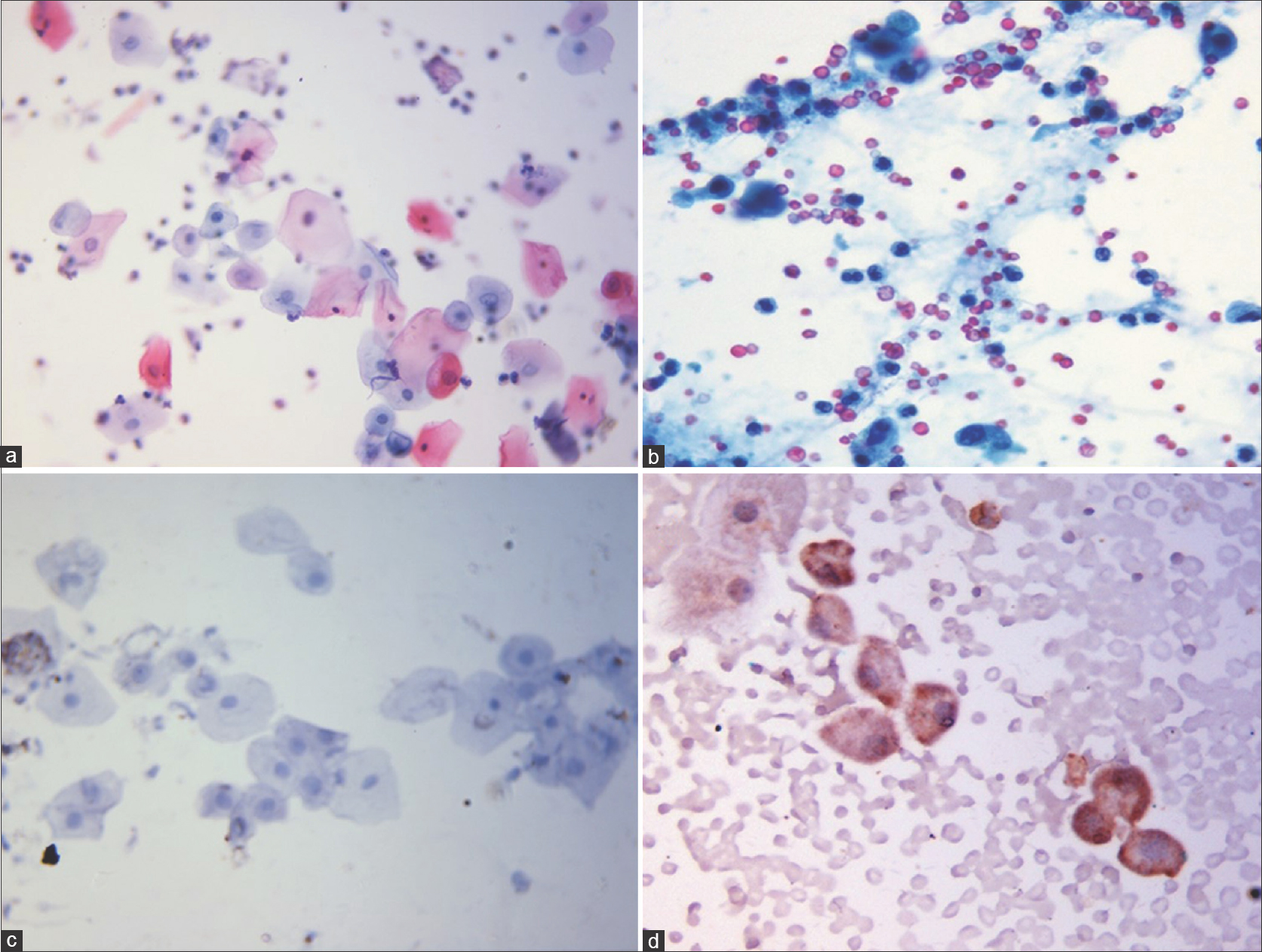

Urine cytology analysis did not reveal atypical or malignant cells in any patient, though four patients showed inconclusive findings of mild nucleomegaly and hyperchromasia [Table - 3]. Both cytokeratin 20 (CK-20) staining [vis-a-vis urine sediments from positive controls, [Figure - 2]a,[Figure - 2]b,[Figure - 2]c,[Figure - 2]d and NMP-22 ELISA were negative in all cases, but the values of the latter were higher in cases showing inconclusive cytologic findings. Cystoscopic examination in these patients with inconclusive urinary cytology showed normal findings in 3 of 4 cases and punctate bleeding points in the bladder mucosa, but without any mucosal pathology or mass in one patient (known case of episodic, gross hematuria since 3 months, first patient in [Table - 2]). On the whole, the cyclophosphamide received by these four patients did not show any differences from that received by the other study subjects in terms of the regimen and the total cumulative dose.

|

| Figure 2: (a-d) Urine cytology composite photomicrograph. (a) Routine cytology image showing normal urothelial cells with small vesicular nucleus and abundant cytoplasm from a study participant (Papanicolaou stain, x100). (b) Urothelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm from a positive control (case of transitional cell carcinoma) (Papanicolaou stain, ×100). (c) Immunocytochemistry for CK 20 showing urothelial cells from a study participant not showing any staining. (CK 20 immunocytochemical stain, x100) (d) Urothelial cells with brown granular cytoplasmic staining for CK 20 from a positive control (case of colon adenocarcinoma). (CK 20 immunocytochemical stain, ×100) |

Overall, cystoscopy was performed in 21 patients [two with hematuria and 19 of 21 patients with symptoms other than hematuria] and was found normal in all, except three patients [Table - 2]. The first case has been discussed with the hematuria cases. Out of the two, one case complained of urinary frequency and occasional nocturia after initiation of cyclophosphamide, which spontaneously resolved despite continuing on medication (cumulative dose 65 g). The other case had urinary frequency, nocturia, and incontinence (cumulative dose 87.6 g). In both cases all other investigations were normal.

Discussion

Urological complications, a major limiting factor in cyclophosphamide use, vary from transient irritative voiding symptoms like urinary frequency, dysuria, urgency, suprapubic discomfort to microscopic hematuria and life-threatening hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder fibrosis, necrosis, cytological atypia of urinary bladder, and bladder carcinoma.[10] The relationship of these side effects with the cumulative dose and duration of cyclophosphamide treatment is still unclear. Symptoms may occur during the course of therapy, or begin several months after discontinuation of the drug.

Cyclophosphamide-associated urological adverse effects are chiefly due to acrolein, a byproduct of hepatic microsomal metabolism that causes urothelial damage by intracellular overproduction of reactive oxygen species, nitrous oxide, and activation of inflammatory cytokine pathways.[3] These mechanisms cumulatively cause bladder mucosal ulceration and hence hemorrhagic cystitis.[3],[9] The incidence of cystitis ranges from 10% to 40%.[11] Despite using aggressive hydration with high-dose cyclophosphamide regimen, the incidence of severe hemorrhagic cystitis ranged from 0.5% to 40%.[12] The dose of oral cyclophosphamide required to induce hemorrhagic cystitis is variable, ranging from 26 g to 129 g, with mean treatment duration of 7–37 months, in autoimmune rheumatologic disorders.[5],[13],[14] As yet, there is no evidence for hemorrhagic cystitis occurring after pulsed regimens. It has been observed that cyclophosphamide, particularly its metabolite phosphoramide mustard, leads to characteristic p53 mutations which may induce bladder cancer.[15] A total cumulative dose ranging from 19 g to 531 g with a mean latency period of 0.6–18 years has been reported for the development of bladder carcinoma.[5],[16],[17] Also, hemorrhagic cystitis in the past is associated with increased risk of bladder cancer in the future but a cause and effect relationship between the two has not been established.[4]

Currently, it is difficult to predict patients who are at risk of urological toxicity to cyclophosphamide. Genetic and constitutional factors have been postulated. Factors contributing to the toxic effect of cyclophosphamide include drug rate, dosage, metabolism, patient hydration, urine output, and voiding frequency.[17]

Cystoscopy is the gold standard for detecting both new and recurrent bladder cancers, but it is both invasive and expensive. Voided urine cytology is a useful screening tool for bladder cancers since it has high specificity (>90%), but variable sensitivity, which is especially poor (20–50%) for low grade neoplasms.[18] Several biomarkers have been studied of which three strip-based tests have been approved by US-FDA, namely NMP-22, bladder tumor antigen (BTA) and fibrin-fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) assay. NMP-22 was found to have a higher median sensitivity, but lower specificity than urine cytology in a meta-analysis (73% and 80% for NMP-22 versus 34% and 99% for cytology, respectively).[19] In a study comparing urine cytology, NMP-22, and CK-20 in the detection of urothelial malignancy, NMP-22 was found to be the most sensitive tool (93%) whereas cytology was most specific (76.5%). Combined use of NMP-22 and cytology increased both the sensitivity and specificity of the latter in detecting malignancy.[20] In another study, CK-20 was found to be an excellent adjunct in patients with atypical urine cytology.[21] Hence, we used NMP-22 and CK-20 as adjuncts to cytology.

Although there is enough literature on the treatment of pemphigus using cyclophosphamide-based regimens, there is paucity on its urological side effects. In a randomized prospective 12-month study on the evaluation of IV CP as adjuvant to oral steroids, none of the patients had microscopic hematuria, though 27% cases developed UTI (versus 11.5% in the steroid alone group).[22] In a study on oral cyclophosphamide in pemphigus, five patients (21.7%) had microscopic or gross hematuria while one case (4.3%) developed bladder cancer 15 years after cyclophosphamide administration.[23] In a large study on 300 pemphigus patients treated with the DCP regimen, the authors found a very low incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis.[24] Absence of significant urological complications in our study could be due to the fact that majority of our patients received the standard DCP regimen which combines IV DCP and low dose oral cyclophosphamide. This carries the dual benefit of being able to reduce the oral cyclophosphamide dose (50 mg/day in DCP regimen versus standard dose of 2–2.5 mg/kg/day) and provide better hydration.

Despite attempting to answer the unique question of urotoxicity of cyclophosphamide regimen in pemphigus that dermatologists are unfamiliar with, our study had a few shortcomings. The relatively small sample size and the inherent lack of a prospective follow-up as part of study design were the limitations.

Conclusion

Chronic cyclophosphamide therapy in pemphigus, as used at our center, is relatively free of serious urological toxicity. Since our patients received mean cyclophosphamide dose of >50 g over 3 years, they could be at risk of developing serious urotoxicity in future. Hence, they should be closely monitored and administered this agent cautiously.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the help rendered in the laboratory work of the study by Ms. Deepali Saxena and Mr. Ijaz Ahmad, junior research fellows in the Department of Pathology, AIIMS, New Delhi.

Financial support and sponsorship

Intramural grant of Institutional Research Fund by the research committee, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Cox PJ. Cyclophosphamide cystitis – Identification of acrolein as the causative agent. Biochem Pharmacol 1979;28:2045-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Manikandan R, Kumar S, Dorairajan LN. Hemorrhagic cystitis: A challenge to the urologist. Indian J Urol 2010;26:159-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Dobrek L, Thor PJ. Bladder urotoxicity pathophysiology induced by the oxazaphosphorine alkylating agents and its chemoprevention. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2012;66:592-602.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Monach PA, Arnold LM, Merkel PA. Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: A data-driven review. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:9-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Talar-Williams C, Hijazi YM, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Hallahan CW, Lubensky I, et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis and bladder cancer in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:477-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Le Guenno G, Mahr A, Pagnoux C, Dhote R, Guillevin L; French Vasculitis Study Group. Incidence and predictors of urotoxic adverse events in cyclophosphamide-treated patients with systemic necrotizing vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1435-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Lawson M, Vasilaras A, De Vries A, Mactaggart P, Nicol D. Urological implications of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2008;42:309-17.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Ersbøll J, Hansen VL, Sørensen BL, Christoffersen K, Hou-Jensen K, et al. Carcinoma of the urinary bladder after treatment with cyclophosphamide for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1028-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Korkmaz A, Topal T, Oter S. Pathophysiological aspects of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide induced hemorrhagic cystitis; implication of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as well as PARP activation. Cell Biol Toxicol 2007;23:303-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Stillwell TJ, Benson RC Jr. Cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. A review of 100 patients. Cancer 1988;61:451-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Watson NA, Notley RG. Urological complications of cyclophosphamide. Br J Urol 1973;45:606-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Carless PA. Proposal for the Inclusion of Mesna (Sodium 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate) for the Prevention of Ifosfamide and Cyclophosphamide (oxazaphosphorine cytotoxics) Induced Haemorrhagic Cystitis; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/17/application/mesna_inclusion.pdf. [Last accessed on 2016 Jan 06].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Townes AS, Sowa JM, Shulman LE. Controlled trial of cyclophosphamide in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1976;19:563-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Reinhold-Keller E, Beuge N, Latza U, de Groot K, Rudert H, Nölle B, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to the care of patients with Wegener's granulomatosis: Long-term outcome in 155 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1021-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Khan MA, Travis LB, Lynch CF, Soini Y, Hruszkewycz AM, Delgado RM, et al. p53 mutations in cyclophosphamide-associated bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998;7:397-403.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Faurschou M, Sorensen IJ, Mellemkjaer L, Loft AG, Thomsen BS, Tvede N, et al. Malignancies in Wegener's granulomatosis: Incidence and relation to cyclophosphamide therapy in a cohort of 293 patients. J Rheumatol 2008;35:100-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Stillwell TJ, Benson RC Jr., DeRemee RA, McDonald TJ, Weiland LH. Cyclophosphamide-induced bladder toxicity in Wegener's granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:465-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Sullivan PS, Chan JB, Levin MR, Rao J. Urine cytology and adjunct markers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Am J Transl Res 2010;2:412-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG. Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: Results of a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses. Urology 2003;61:109-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Srivastava R, Arora VK, Aggarwal S, Bhatia A, Singh N, Agrawal V. Cytokeratin-20 immunocytochemistry in voided urine cytology and its comparison with nuclear matrix protein-22 and urine cytology in the detection of urothelial carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol 2012;40:755-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Lin S, Hirschowitz SL, Williams C, Shintako P, Said J, Rao JY. Cytokeratin 20 as an immunocytochemical marker for detection of urothelial carcinoma in atypical cytology: Preliminary retrospective study on archived urine slides. Cancer Detect Prev 2001;25:202-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Evaluation of cyclophosphamide pulse therapy as an adjuvant to oral corticosteroid in the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol 2013;38:659-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Cummins DL, Mimouni D, Anhalt GJ, Nousari CH. Oral cyclophosphamide for treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:276-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, Chandra M. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol 1995;34:875-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,858

PDF downloads

1,820