Translate this page into:

Occupational contact dermatitis among construction workers: Results of a pilot study

Correspondence Address:

Vikram K Mahajan

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Dr. R. P. Government Medical College, Kangra (Tanda) - 176 001, Himachal Pradesh

India

| How to cite this article: Sharma V, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS. Occupational contact dermatitis among construction workers: Results of a pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014;80:159-161 |

Sir,

The Indian construction industry employs more than 4 million (skilled or unskilled) workers yet there are few studies pertaining to occupational contact dermatitis among construction workers from our country. We studied 50 male construction workers (39 masons, 10 laborer/helpers, 1 painter) aged between 22 and 70 years having occupation-related contact dermatitis. Patch testing was undertaken with Indian standard series by Finn chamber method. We also patch tested 10 controls who were all men between 20-40 years old and were either healthy volunteers or had minor dermatoses (dermatophytosis, onychomycosis or scabies) and no dermatitis or exposure to relevant allergens. Clinical details were recorded and the relevance of positive patch test results was determined clinically.

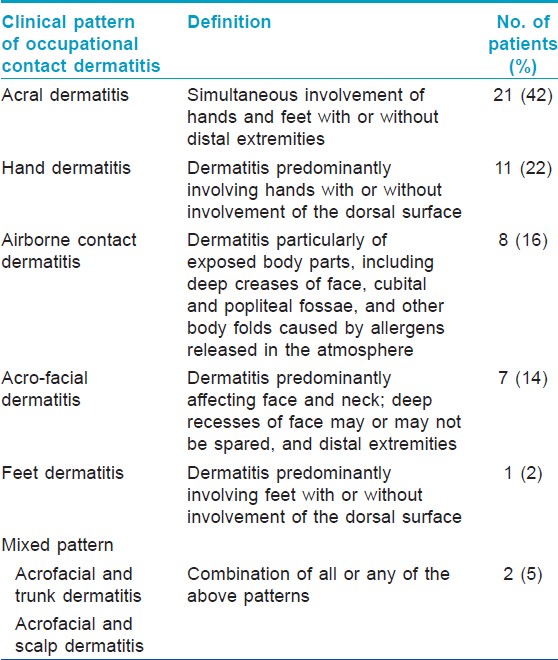

As the construction industry employs a significant number of young individuals, the majority 41 (82%) of our patients were 25-50 years old. They had been in construction work for 2-40 (average 14.5) years; 45 (90%) patients were in the occupation for ≥5 years. The mean duration of contact dermatitis was 14 years corroborating the observation that skin problems usually develop after a median period of 12 years in construction and cement workers. [1] All our patients had acute, subacute, chronic lichenified dermatitis or occasionally ulcerative hand dermatitis for 1 month to 20 (average 3.5) years and remissions during off days. The common clinical patterns [Table - 1] observed by us have been reported previously [2],[3],[4] and include acral dermatitis, hand dermatitis, air-borne contact dermatitis (ABCD) pattern, acrofacial dermatitis, mixed pattern and feet dermatitis in order of frequency. Ulcerative dermatitis/chrome ulcers and hyperkeratotic irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) were noted in 16 (32%) and 10 (20%) patients respectively [Figure - 1]. Acral or hand dermatitis, or air-borne contact dermatitis is expected to be frequent among construction workers due to direct contact during mixing, handling or spreading concrete, or from air-borne dissemination of allergens.

|

| Figure 1: Occupational contact dermatitis in construction workers: (a) Acral dermatitis involving hands and feet. This patient also had dermatitis of forearms. (b) Hand dermatitis: Characteristic "chrome ulcers" over ring fingertips. (c) Hand dermatitis: Hyperkeratotic irritant contact dermatitis variety. (d) Hand dermatitis: Ulcerative dermatitis variety |

Overall, all patients had positivity to at least 1 patch test allergen with 109 positive patch tests in the study group. The tests showed definite relevance in 96% of patients. Potassium dichromate in 46 (92%) and cobalt chloride in 21 (42%), the most common sensitizers observed in our study are reported to be the major contact sensitizer among 20-41% construction workers while cobalt along with epoxy resins and nickel have been the second most occupationally relevant contact sensitizers. [3],[4] Chrome ulcers were observed in 16 (32%) patients. Water-soluble hexavalent chromate (potassium dichromate) in wet cement has a corrosive effect causing irritant contact dermatitis among those who are regularly exposed to it or have irritant/corrosive effects (deep cement burns from alkaline lime) in untrained workers. Forty six (92%) of our patients with potassium dichromate positive patch test reactions had characteristic dry and hyperkeratotic irritant contact dernatitis and/or ulcerative dermatitis suggesting that ICD from chromates in cement, even when minimal, predisposes to occupational allergic contact dermatitis. The irritant effect and alkalinity of potassium dichromate/cement synergistically compromise skin barrier function facilitating penetration causing contact sensitization to chromates after years. Cobalt is reported to be the second most common contact sensitizer accounting for 20% cases following chromate allergy which occurs in 41%. [4] Twenty one (42%) of our patients had a positive reaction to cobalt. Concurrent chromate and cobalt, and nickel and cobalt sensitivity occurred in 20 (40%) and 1 (2%) patients respectively. However, cobalt is not known to cross react with chromate or nickel and isolated cobalt sensitivity is not uncommon in construction workers. [5] Positive reactions were also noted to mercapto mix and mercaptobenzothiazole in 3 (6%) and 5 (10%) patients, fragrance mix and thiuram mix in 4 (8%) and nickel sulfate and p-phenylenediamine in 2 (5%) patients respectively. Contact sensitivity to these allergens is likely to be due to exposure to rubber/leather (gloves, boots), epoxy resins, glues (phenol and urea-formaldehyde), hardwoods, tools and metal cleansers, acrylates and varnish (urea-formaldehyde), the common work materials in this occupation. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7] Interestingly, nearly 50% of cases of rubber allergy in construction workers occurs from rubber protective gear. [7] One patient who had aggravation of dermatitis from rubber gloves showed positive reaction to rubber chemicals (mercapto mix, mercaptobenzothiazole). Contact sensitivity to neomycin, wool alcohol, benzocaine in 1 (2%) patient each, parabens and balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae) in 2 (4%) and fragrance mix in 4 (8%) patients respectively in our patients is perhaps from non-occupational causes as all these are components of topical medications, cosmetics, perfumes and pharmaceuticals. Parthenium hysterophorous due to its ubiquitous presence in India appears to be a frequent contact sensitizer in this set of workers as well and caused occupationally relevant positive reactions in 15 (30%) patients. Polysensitivity to ≥2 allergens occurred in 34 (68%) patients; 2 patients each had sensitivity to 5 allergens potassium dichromate, cobalt chloride, mercaptomix, mercaptobenzothiazole, Parthenium). This appears to be from simultaneous exposure and non-specific hyper-reactivity as cross reactions between these allergens have not been documented. Only one control, a 21-year-old cook, had a positive reaction to potassium dichromate attributable to non-occupational exposure.

The clinico-epidemiologic and allergologic profile of contact dermatitis among construction workers from Himachal Pradesh, where lately there has been substantial construction for roads, hydroelectric projects, housing and industry, is comparable to previously reported studies. However, studies in each area are important as the list of contactants may vary across regions and times according to the prevalent patterns of designs, architecture, local materials and the type of construction.

| 1. |

Fregert S, Gruvberger B. Solubility of cobalt in cement. Contact Dermatitis 1978;4:14-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Bock M, Schmidt A, Bruckner T, Diepgen TL. Occupational skin disease in the construction industry. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:1165-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Sarma N. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis among construction workers in India. Indian J Dermatol 2009;54:137-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Condé-Salazar L, Guimaraens D, Villegas C, Romero A, Gonzalez MA. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis in construction workers. Contact Dermatitis 1995;33:226-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Hegewald J, Uter W, Pfahlberg A, Geier J, Schnuch A, IVDK. A multifactorial analysis of concurrent patch-test reactions to nickel, cobalt, and chromate. Allergy 2005;60:372-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Macedo MS, de Avelar Alchorne AO, Costa EB, Montesano FT. Contact allergy in male construction workers in Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2000-2005. Contact Dermatitis 2007;56:232-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Conde-Salazar L, del-Río E, Guimaraens D, González Domingo A. Type IV allergy to rubber additives: A 10-year study of 686 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29:176-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,969

PDF downloads

1,578