Translate this page into:

A randomized, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) versus miltefosine in patients with post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

Corresponding author: Dr. Krishna Pandey, Department of Clinical Medicine, Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Agamkuan, Patna - 800 007, Bihar, India. drkrishnapandey@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pandey K, Pal B, Siddiqui NA, Lal CS, Ali V, Bimal S, et al. A randomized, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) versus miltefosine in patients with post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:34-41.

Abstract

Background:

Treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases is of paramount importance for kala-azar elimination; however, limited treatment regimens are available as of now.

Aim:

To compare the effectiveness of liposomal amphotericin B vs miltefosine in post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis patients.

Methodology:

This was a randomized, open-label, parallel-group study. A total of 100 patients of post kala azar dermal leishmaniasis, aged between 5 and 65 years were recruited, 50 patients in each group A (liposomal amphotericin B) and B (miltefosine). Patients were randomized to receive either liposomal amphotericin B (30 mg/kg), six doses each 5 mg/kg, biweekly for 3 weeks or miltefosine 2.5 mg/kg or 100 mg/day for 12 weeks. All the patients were followed at 3rd, 6th and 12th months after the end of the treatment.

Results:

In the liposomal amphotericin B group, two patients were lost to follow-up, whereas four patients were lost to follow-up in the miltefosine group. The initial cure rate by “intention to treat analysis” was 98% and 100% in liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine group, respectively. The final cure rate by “per protocol analysis” was 74.5% and 86.9% in liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine, respectively. Twelve patients (25.5%) in the liposomal amphotericin B group and six patients (13%) in the miltefosine group relapsed. None of the patients in either group developed any serious adverse events.

Limitations:

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was not performed at all the follow-up visits and sample sizes.

Conclusion:

Efficacy of miltefosine was found to be better than liposomal amphotericin B, hence, the use of miltefosine as first-line therapy for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis needs to be continued. However, liposomal amphotericin B could be considered as one of the treatment options for the elimination of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent.

Keywords

Indian subcontinent

kala-azar elimination

liposomal amphotericin B

miltefosine

post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

Introduction

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis is a skin disorder, commonly occurring in poor people living in a rural area. It occurs in 5–10% of treated visceral leishmaniasis cases within 6 months to 2 years of receiving treatment.1 Female sandfly Phlebotomus argentipes is the responsible vector for transmission of this disease. Other than skin rashes post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis patients are apparently healthy1. Macular, papular, nodular lesions or mixture of these are the common clinical presentations of the disease. It may occurs all on over the body but is most commonly seen on the face. Earlier it was reported to occur among patients receiving treatment with sodium antimony gluconate for their visceral leishmaniasis episode. But a recent study has documented its occurrence with all the available antileishmanial drugs such as miltefosine, paromomycin, liposomal amphotericin B and even with combination therapy of miltefosine-paromomycin.2-5

Miltefosine is the only leishmanicidal drug used orally for the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. It is recommended as first-line therapy for the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in India. It is used in children in the dose of 2.5 mg/kg/day and for adults 100 mg/day for a period of 12 weeks.6 As with other antileishmanial therapy it also has several limitations. It is associated with gastrointestinal side effects and poor treatment adherence. Besides, it is also contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women.6 Amphotericin B is another therapeutic option and can be used in patients in whom are have contraindicated with miltefosine cannot be used. It is used at a dose of 1 mg/ kg for 60–80 infusions.7 It is also found to be effective at a low dose of 0.5 mg/kg and 0.75 mg/kg.8,9 Like miltefosine, it also has some limitations. Nausea, vomiting, fever, rigors and nephrotoxicity are some of the commonly occurring adverse drug reactions associated with this therapy.7

Methodology

Study design and sample size

This was a prospective, open-label, randomized, parallel-group study. Due to the limited availability of resources, actual sample size calculation was not attempted.

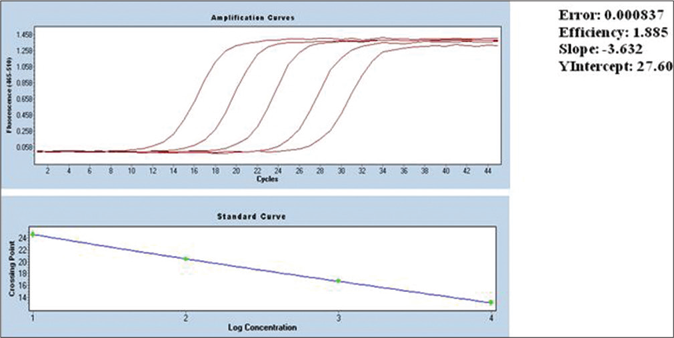

Patients of both genders, aged between 5 and 65 years were enrolled in the study. Baseline evaluations of all the participants were done which included complete hemogram, liver function test (alanine aminotransaminase/aspartate aminotransaminase, bilirubin), kidney function test (serum urea and creatinine) and serum electrolytes (sodium and potassium). Patients, seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis, suffering from any malignancy and any other infectious diseases were excluded from the study. Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded. Patients were randomized based on sequentially numbered sealed envelopes prepared from a computer-generated randomization sequence. Clinical examination of skin lesions and positive immuno chromatographic rK39 strip test was used for screening of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases. All the potential patients were further processed through microscopical observation of parasites through a slit-skin smear after Giemsa staining and by quantitative polymerase chain reaction study. Gradation of the parasitic burden in skin smear microscopy was done as per the World Health Organization criteria.10 Only quantitative polymerase chain reaction positive cases were included in the study. The diagnosis was confirmed by measuring the parasitic burden by using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction using SYBR green technology.11 A parasitic load of 15/μg of DNA (cycle threshold value 33) was considered to be a positive case for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. The amplification curve for standard in quantitative polymerase chain reaction studies is presented in Figure 1. The quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed at diagnosis and 12-month follow-up.

- Standard curve for quantitative polymerase chain reaction

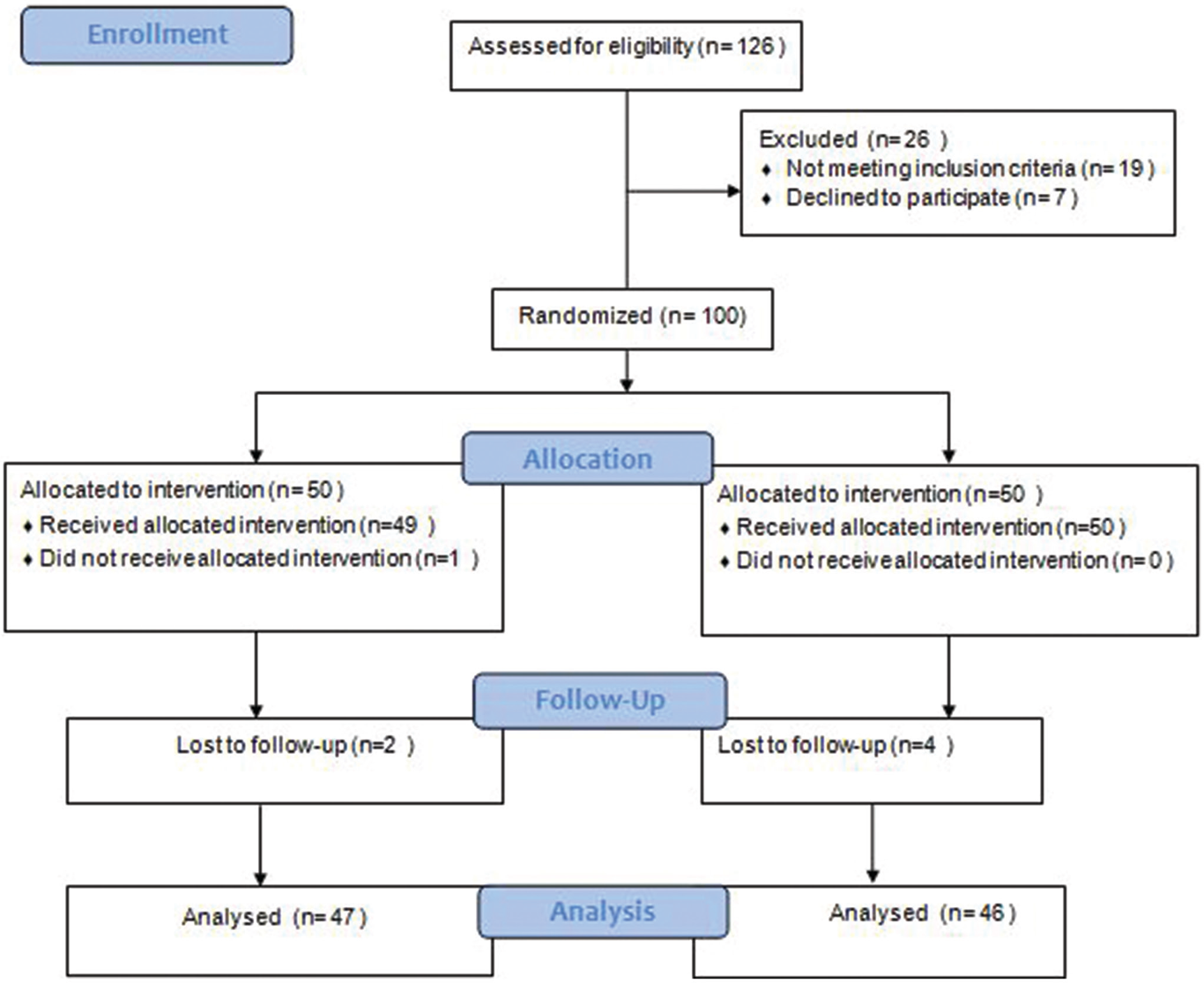

A total of 126 patients were screened for eligibility and seven patients did not agree to take part in the study. Another 19 patients were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria. Thus, a total of 100 patients were enrolled in the study, 50 patients in each of the groups A and B. Patients were randomized to receive liposomal amphotericin B for a total dose of 30 mg/kg, administered in six doses of 5 mg/kg, biweekly for 3 weeks (group A) or miltefosine in the dose of 2.5 mg/kg or 100 mg/day for 12 weeks (group B). All the patients in group A were admitted for the entire duration of treatment (3 weeks), whereas patients in group B were given miltefosine for 28 days and discharged from the hospital. They were advised to return after 28 days. This was repeated in each subsequent course. All patients (both groups A & B) were requested to come for follow-up visits at 3, 6 and 12 months after the end of treatment.

Study setting

This study was done at the Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Indian Council of Medical Research, Patna, India from March 2017 to October 2018. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna. The study was performed in compliance with the protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Consent was also obtained from legal guardians in the case of minor patients. Informed consent was presented in the Hindi language.

Efficacy

Efficacy was measured by the initial and final cure. The initial cure was defined as the disappearance of nodular and papular lesions and/or no appearance of new macular lesions together with grade 0 parasitemia score in skin tissue after treatment. The final cure was defined as complete disappearance of all papular/nodular lesions, complete or almost complete resolution of macular lesions, no reappearance of new lesions and grade 0 parasitemia scores or insignificant parasitic burden in the skin at 12-month follow-up. Therapeutic failure was considered when there was no improvement of dermal lesions after treatment as well as positive parasitemia scores in skin biopsy, whereas the appearance of a new lesion in skin together with positive parasitemia score within 12 months of follow-up was considered as relapse.

Safety

Patients in group A were kept under close supervision for the identification of any adverse events on a daily basis. All the biochemical and hematological investigations which included complete hemogram, liver function test (alanine aminotransaminase/aspartate aminotransaminase, bilirubin), kidney function test (serum urea and creatinine) and serum electrolytes (sodium and potassium) were done once at every week till treatment completion in case of group A. Whereas, in group B these tests were performed once at every 4 weeks. These investigations were also repeated at 3, 6 and 12 months follow-up visits.

Rescue therapy

Amphotericin B in the dose of 1 mg/kg bodyweight for 60– 80 infusions in 5% dextrose on alternate days at a 15-day interval was the rescue treatment in cases of relapse or treatment failure.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 16). Descriptive statistics were used to describe continuous variables under the study. Intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses with 95% confidence interval were used for estimation of initial and final cure rate. A Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. A probability value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry- India (CTRI), number CTRI/2018/05/014015.

Results

Study subjects comprised 19 men and 31 women in group A, whereas group B consisted of 37 men and 13 women. Mean (±SD) age of the participants in groups A and B were 23.4 (± 12.8) years and 28.9 (±18.7) years, respectively. Eighty nine patients (89%) had a past history of visceral leishmaniasis and eleven patients (11%) did not report a history of having been treated for visceral leishmaniasis. Forty three patients had been treated with sodium antimony gluconate, ten with miltefosine, nine with liposomal amphotericin B and five with amphotericin B for their past illness of visceral leishmaniasis. Remaining 22 patients were not aware of their treatment history. Seventy patients had monomorphic lesions (either macular, papular or nodular) and 30 had a mixture of macular, papular and nodular lesions. The details of clinicoepidemiological profiles of both groups are depicted in Table 1.

| Variables | Group A Liposomal amphotericin B (n=50), n(%) | Group B Miltefosine (n=50), n(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (±SD) | 23.4 (±12.8) | 28.9 (±18.7) |

| Male | 19 (38) | 37 (64.9) |

| Female | 31 (62) | 13 (22.8) |

| Yes | 46 (92) | 43 (86) |

| No | 4 (8) | 7 (14) |

| SAG | 20 (43.5) | 23 (53.5) |

| Miltefosine | 6 (13) | 4 (9.3) |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | 4 (8.7) | 5 (11.63 |

| Amphotericin B | 4 (8.7) | 1 (2.3) |

| Unknown | 12 (26.1) | 10 (23.3) |

| Monomorphic | 34 (68) | 36 (72) |

| Polymorphic | 16 (32) | 14 (28) |

VL: visceral leishmaniasis; SAG: sodium antimony gluconate; n: total number of patients; SD: standard deviation

Efficacy

Two patients from the liposomal amphotericin B group did not turn up for follow-up visits, whereas in the miltefosine group, four patients were lost to follow-up. In the liposomal amphotericin B group, upon completion of treatment, all the papular and nodular lesions disappeared; however, macular lesions persisted as it takes longer time for repigmentation. The same was also observed in the miltefosine group. All the papular and nodular lesions disappeared on completion of treatment and macular lesions took the longest time to disappear. At the 3-month follow-up, all the papular and nodular lesions healed completely and macular lesions were faded and decreased in number and no new lesions reappeared in both the groups. At the 6-month follow-up, macular lesions had almost disappeared in both the groups except that one patient in group A developed new lesions. However, the quantitative polymerase chain reaction of this patient was found to be negative.

At the time of diagnosis, all the patients were highly parasitemic (median parasitic score of Group A and B were 6312 parasites/μg of DNA and 6088 parasites/μg of DNA, respectively). At the 12-month follow-up, all the patients in group B had negligible parasites except in six relapsed cases. The mean parasitic scores of these 6 cases were 17 parasites/ μg of DNA. Similarly, apart from 12 relapsed cases (mean parasitic score was 19 parasites/μg of DNA) all the patients in group A had negligible parasites. Relapsed cases in both groups had reappearance of lesions. The standard curve for the quantitative polymerase chain reaction and patients’ flow diagram are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

- Patients’ flow diagram

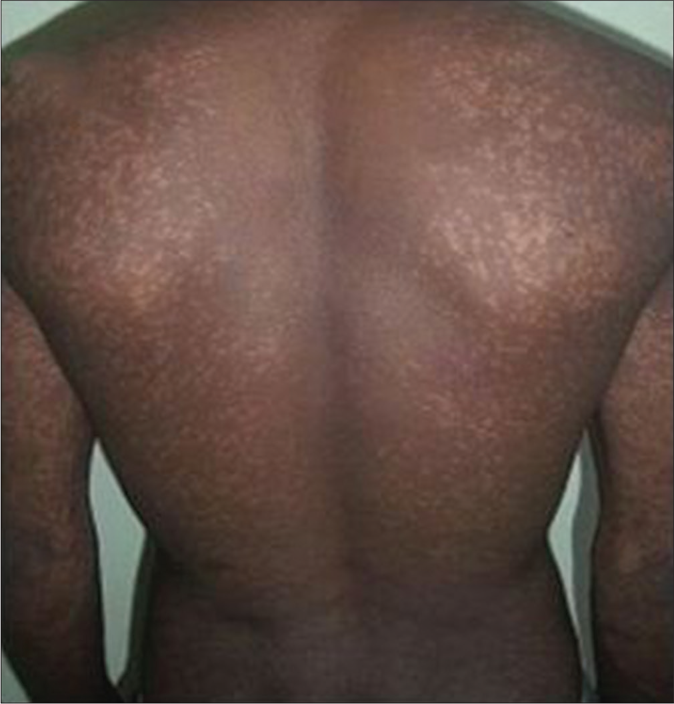

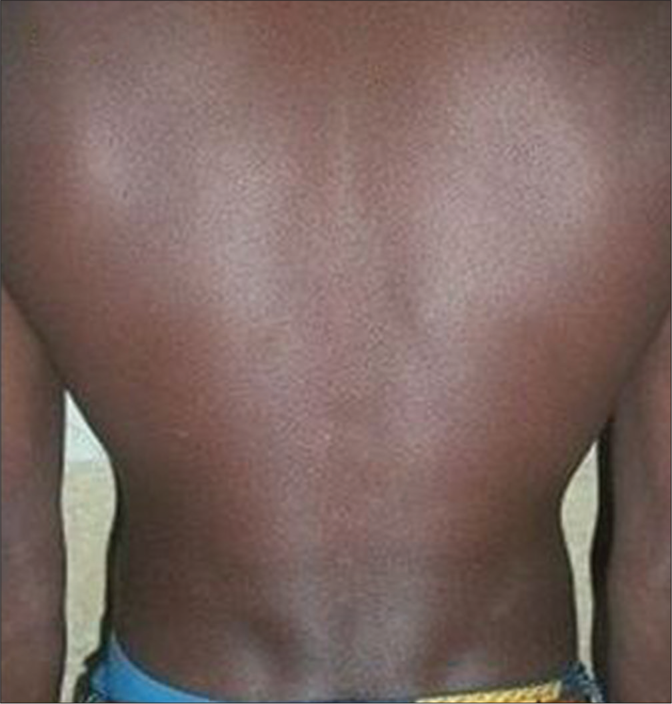

An initial cure was achieved in 49 patients in the liposomal amphotericin B group and all 50 patients in the miltefosine group. The initial cure rate by intention to treat analysis was 98% and 100% in liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine group, respectively. The final cure rate by per-protocol analysis was 74.5% (95% confidence interval 59.4–85.6%) and 86.9% (95% confidence interval 73.05–94.6%) in liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine group, respectively. A representative example of a cure in both the regimens is presented in Figures 3 and 4. Twelve patients (25.5%) in the liposomal amphotericin B group and six patients (13%) in the miltefosine group relapsed. The treatment response of two different groups is presented in Table 2. All the relapsed cases were treated with amphotericin B in a dose of 1mg/kg alternate days for 60–80 infusions.

- PKDL patient before treatment with liposomal amphotericin B

- After 12 months of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B

- Macular lesions in a PKDL patient before treatment with miltefosine

- After 12 months of treatment with miltefosine

| Response | Group A (n=50), n(%) | Group B (n=50), n(%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial cure | 49/50 (98) | 50/50 (100) | -* |

| Final cure | 35/47 (74.5) | 40/46 (86.9) | 0.00 |

| Relapse rate | 12/47 (25.5) | 6/46 (13.0) | 0.00 |

Safety

A total of 41 (82%) patients in group A and 28 (56%) in group B experienced adverse events. Vomiting was the predominant adverse effect occurring in 18 patients in the miltefosine group, whereas only nine patients experienced the same in the liposomal amphotericin B group. Elevated hepatic enzymes were observed in 9 patients in group A and 11 patients in group B. Increased serum creatinine was observed in nine patients and seven patients in group A and group B, respectively. Hypokalemia, which was one of the limiting factors with the usage of liposomal amphotericin B, was found in six patients; however, these patients were asymptomatic. Low back pain was experienced by three patients in the liposomal amphotericin B group. All the adverse effects were either common terminology criteria grade I or II and did not require any major intervention or dose modification. Other adverse effects experienced by both the groups were anorexia, pain in abdomen/back, headache, gastritis, etc. None of the patients experienced any serious adverse events. The details of the occurrence of adverse effects during the entire study duration are presented in Table 3.

| AEs | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Group A Liposomal amphotericin B (n=50) | Group B Miltefosine (n=50) | |

| Nephrotoxicity | 9 | 7 |

| Hypokalemia | 6 | 1 |

| Headache | 7 | 1 |

| Gastritis | 1 | 2 |

| Low back pain | 3 | |

| Elevated liver enzymes (ALT/AST) | 9 | 11 |

| Elevated bilirubin | 1 | 1 |

| Eosinophilia | 17 | 11 |

| Anorexia | 14 | 7 |

| Hyperuricemia | 2 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 9 | 18 |

| Cough | 8 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 2 | 1 |

| Itching | 7 | |

| Abdominal pain | 3 | 8 |

| Body ache | 4 | |

| Fiver/rigors | 9 | 2 |

| RBC increased | 2 | 1 |

| Pain at injection site | 4 | |

| Weakness | 3 | 1 |

| Anemia | 3 | |

| Leucopenia | 1 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | |

| Chest pain | 2 | |

| Angioedema | 3 | |

| Others | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 130 | 83 |

AEs: adverse events; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase

Discussion

All the treatment options available for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis are of longer duration, expensive and associated with several side effects and contraindications. Therefore, it is the need of the hour to find a safe, short course, affordable and cost-effective therapeutic regimen for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, especially when we are on the verge of kala-azar elimination. It has also been emphasized in many published literature to find out a that a short course, safe and affordable therapeutic option for the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis is urgently the need of the hour. Liposomal amphotericin B has been recommended as a first-line therapeutic option for the elimination of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent due to its good safety and efficacy profile. In Ethiopia, liposomal amphotericin B has been tried in different doses ranging from less than 24 mg/ kg to 35 mg/kg (total dose) in the treatment of severe visceral leishmaniasis cases.12 The initial cure rate was found to be 96.7% at with a high dose (24-35 mg/kg total dose) versus 80.2% using a low dose (<24 mg/kg total dose). These results indicate that a higher dose produces a better therapeutic outcome. Hypokalemia and infusion-related reactions were the common adverse events occurring in both groups.12 In a recent study, under the Médecins Sans Frontières program in Bangladesh large number of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases (approximately 1400) were treated on an ambulatory basis with liposomal amphotericin B with a total dose of 30 mg/kg body weight.13 Subsequently, another study from the same region was tried conducted by reducing the to a total dose to 15 mg/kg in post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis patients.13 In both studies, treatment outcome was satisfactory and none of the patients experienced any serious adverse events. In both the above mentioned studies, diagnosis and the therapeutic outcome were based on clinical evaluation and no parasitological assessment was done. Besides, laboratory investigations for safety evaluations were not performed. In this study, we aimed to assess the comparative efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B for a total dose of 30 mg/kg given in six doses of 5 mg/kg biweekly regimen over 3 weeks vs miltefosine at a dose 2.5 mg/kg or 100 mg/day for 12 weeks in post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis patients.

Liposomal amphotericin B is a liposomal preparation of conventional amphotericin B. It was formulated to minimize some major drawbacks such as nephrotoxicity, associated with the conventional preparation. It acts by binding with the cell membrane component, ergosterol, resulting in an alteration of cell membrane permeability followed by cell death. Due to the excellent safety and efficacy profile of liposomal amphotericin B it has been considered by the World Health Organization as the first-line choice of drug for the elimination of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent. The Government of India plans to eliminate kala-azar by 2020. The main objective of this elimination program includes quick diagnosis and vector management with insecticidal residual spray as well as treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases. The same therapy has also been adopted by the Indian vector-borne disease control program. This drug has been recommended as single-shot preparation of 10 mg/ kg for visceral leishmaniasis to meet the elimination target rapidly. Apart from its effectiveness, liposomal amphotericin B also has a higher compliance rate due to single-dose formulation, is suitable for pregnant and lactating women and can also be used in children. 14 It requires a shorter period of hospitalization and is convenient to use in a rural hospital for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. 15 Miltefosine, being convenient oral formulation and having satisfactory treatment outcome, has been placed as a first-line therapeutic regimen for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Without treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases kala-azar elimination will not be achieved as post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases are considered as a reservoir of Leishmania parasites.

With regard to the safety profile, the incidence of adverse effects in the liposomal amphotericin B group was found to be high when compared to the miltefosine group. This could be because all the patients in the liposomal amphotericin B group remained hospitalized throughout the treatment course, whereas patients receiving miltefosine were treated on an ambulatory basis. Vomiting was found to be the most commonly occurring adverse effects experienced by the patient in the miltefosine group, whereas, the incidence of vomiting in the liposomal amphotericin B group was found to be less. Gastrointestinal side effects are well-known side effects associated with miltefosine therapy. However, none of the patients in either group was withdrawn from the study due to adverse effects. All the adverse effects were common terminology criteria grade I or grade II. None of the patients experienced grade III or grade IV adverse effects. Nephrotoxicity, which is the most common side effect associated with amphotericin B, was experienced by nine patients in the liposomal amphotericin B group, whereas seven patients experienced the same in the miltefosine group. The serum creatinine level of all these patients in either group was between 1.2 and 2.5. The nephrotoxicity was managed by withholding the treatment until serum creatinine became normal. Mild hypokalemia was experienced by six patients in the liposomal amphotericin B group and only one patient in the miltefosine group. The hypokalemic patients were asymptomatic and none of the patients developed rhabdomyolysis. All the adverse effects were managed within the hospital settings. None of the patients developed any serious adverse events.

Efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B therapy was found to be satisfactory (cure rate 74.5%) but lesser than miltefosine (cure rate 86.9%). Our results were similar to that of Moulik et al.16 Relapse rate for miltefosine therapy in our study was found to be 13%. In a study by Ramesh et al., the relapse rate increased to 15% (11 relapses) from 4% between 12 and 18 months.17 In an earlier study by Sundar et al., miltefosine 100 mg/kg cure rate was found to be 93% at 12 weeks. 18 Another study by Ramesh et al., reported similar results with 26 patients. 19 Liposomal amphotericin B in the dose of 2.5 mg/kg daily for 20 days in Sudanese post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases showed the final cure rate to be 83% without any adverse events. 20 In a recent study in Bangladesh, with 273 post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis patients, treated with liposomal amphotericin B {total dose of 15 mg/kg body weight}, complete or major improvement of skin lesions was observed in an even higher proportion (89.7%) of patients. 11

Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the sample size. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was not performed at the completion of treatment and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Conclusion

Efficacy of miltefosine was found to be superior compared to liposomal amphotericin B. Therefore, continued use of miltefosine as a first-line therapy for the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis is recommended. However, liposomal amphotericin B may be considered as one of the options for the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis for whom miltefosine is contraindicated. Controlled clinical trials with larger sample size are warranted to verify the effectiveness of this therapy in post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Future studies with the combination of liposomal amphotericin B with miltefosine at different dosages can be tried to explore the efficacy and safety of this combination regimen for a shorter course.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Kanhaiya Agarwal, Naresh Kumar Sinha and Shanthi Sister for their cooperation during the entire duration of the study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Development of post-Kala-Azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in miltefosine-treated visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:336-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in a patient treated with injectable paromomycin for visceral leishmaniasis in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1478-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post Kala-Azar dermal leishmaniasis following treatment with 20 mg/kg liposomal amphotericin B (Ambisome) for primary visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2611.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PKDL development after combination treatment with miltefosine and paromomycin in a case of visceral leishmaniasis: First ever case report. J Med Microbiol Immunol Res. 2018;2:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inadequacy of 12-week miltefosine treatment for Indian post-Kala-Azar dermal leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:767-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amphotericin B is superior to sodium antimony gluconate in the treatment of Indian post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:611-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To evaluate efficacy and safety of amphotericin B in two different doses in the treatment of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174497.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amphotericin B treatment for Indian visceral leishmaniasis: Response to 15 daily versus alternate-day infusions. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:556-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quantitation of amastigotes of Leishmania donovani in smears of splenic aspirates from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:475-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reliable diagnosis of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) using slit aspirate specimen to avoid invasive sampling procedures. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:268-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of complicated visceral leishmaniasis in patients without HIV, North-West Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:548.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety and effectiveness of short-course Liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of Post-Kala-azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL): A prospective cohort study in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:667-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in children and adolescents at a tertiary care center in Bihar, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:1498-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in a rural public hospital in Bangladesh: A feasibility study. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:E51-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring of Parasite Kinetics in Indian Post-Kala-azar Dermal Leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:404-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decline in clinical efficacy of oral miltefosine in treatment of post Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:E0004093.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral miltefosine for Indian post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: A randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:96-100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltefosine as an effective choice in the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:411-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B (Liposomal amphotericin B) in the treatment of persistent post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99:563-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]