Translate this page into:

A study of allergen-specific IgE antibodies in Indian patients of atopic dermatitis

Correspondence Address:

V K Somani

17 A Journalist Colony, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh

India

| How to cite this article: Somani V K. A study of allergen-specific IgE antibodies in Indian patients of atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:100-104 |

Abstract

Background: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, pruritic dermatitis frequently associated with the hyperproduction of IgE to various allergens. Identification of these allergens is possible by various laboratory investigations. Aim: The present study was designed to assess these allergen-specific antibodies in the diagnosis of AD in the Indian context. Methods: This prospective study comprised 50 patients of AD. The diagnosis was made clinically after satisfying Hanifin and Rajka's criteria. Serum IgE levels were estimated and specific IgE antibodies were measured for 20 food allergens and aeroallergens. Results: Serum IgE was elevated in 88% of the patients. The highest elevation of mean IgE levels was seen in the 10-20 years age group. Sixty five percent of the children under the age of ten years were positive to one or more food allergens. Food allergens were more often positive in the ≤10 years age group and specific antibodies to inhalants were seen more frequently in the older age groups. Specific antibodies to apples were found in all age groups. Conclusion: Antibodies against apples and hazelnuts were the more commonly seen specific antibodies in children. Incidence of positivity was much higher in children when compared to earlier studies. Identification of food allergens can be an important factor in the diagnosis of AD in children in India. Positivity to inhalant allergens in the older age groups was lower in this study. The allergen profile with regard to inhalants in Indian patients was similar to that of earlier studies.

Introduction

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, extremely pruritic dermatitis in which there is a propensity to increased production of IgE to environmental allergens. AD, along with bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis is included in atopic group of diseases. Recent prevalence surveys suggest that about 10-20% of children in developed countries suffer from AD. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7] AD has a complex etiology that encompasses immunologic responses, susceptibility genes, environmental triggers, and compromised skin-barrier function.

It is difficult to define AD because of its intermittent nature, varying clinical picture with age, and the diversity of clinical presentations. One of the main reasons for slow understanding of the epidemiology of AD is lack of a standardized, specific diagnostic test to confirm AD. Various excellent attempts have been made to lay down a specific set of criteria to aid in accurate diagnosis of AD. Most noteworthy among these are Hanifin and Rajka′s criteria, [8] UK Working Group classification [9] and the millennium criteria. [10]

Millennium criteria for the diagnosis of AD include:

1. Mandatory criteria: presence of allergen-specific IgE:

- historical, actual or expected (in very young children)

- in peripheral blood (radioallergosorbent test (RAST), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)) or in skin (intracutaneous challenge)

2. Principal criteria (two of three present)

- Typical distribution and morphology of eczema lesions: infant, childhood or adult type

- Pruritus

- Chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis

Total serum IgE is elevated in over 80% of patients with AD. Specific IgE antibodies directed against environmental antigens can be detected in most AD patients. Up to 100% children with associated respiratory atopy have positive RASTs for airborne allergens and 80% are positive to foods. In children with only AD, elevated specific IgE can be found in about 20%. [11] However, even though total IgE levels may be normal, there are almost always specific IgEs directed at environmental aero and/or food allergens. [12] The levels of IgE generally correlate with the severity of the dermatitis and are greatly elevated if there is concomitant respiratory atopy. The aim of the present study was to observe the occurrence of specific IgEs in patients of AD in relation to age and total IgE levels in the Indian context.

Methods

Fifty consecutive patients of AD were included in the study. All the patients underwent clinical examination and were diagnosed as AD after fulfilling the Hanifin and Rajka′s criteria. There were 27 males and 23 females in the group and their age ranged from one to 24 years. Patients were recruited from an outpatient clinic in Hyderabad in South India, over a period of nine months from March 2006 to December 2006. All the patients in the study group were examined to rule out any other illness. Other allergic diseases with elevated IgE like allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, food anaphylaxis, Netherton′s syndrome, hyper IgE syndrome, immunodeficiency syndromes etc were excluded. Patients of AD who were on other treatment modalities like topical or oral steroids or immunosuppressive drugs were excluded. A detailed history including family history was taken.

Blood samples were collected for serum IgE estimation and the atopic immune profile. The immune profile entailed estimation of IgE antibodies against various inhalation and food allergens with the help of the Enzyme Allergo Sorbent Test (EAST) which was performed using Euroimmune ® kits (Medizinische Labordiagnostica, Germany).

The Euroline test kit provides a semiquantitative in vitro assay for human IgE antibodies to inhalation and food allergens in serum. The kit contains test strips coated with parallel lines of 20 different allergen extracts [Table - 1]. The test strips are first moistened and then incubated in the first reaction step with patient serum. If samples are positive for that allergen, specific antibodies of class IgE will bind to the allergens. To detect the bound antibodies, a second incubation is carried out using an enzyme-labeled monoclonal anti-human IgE (enzyme conjugate), which catalyzes a color reaction.

By using a digital evaluation system, the intensity of bands was calculated in EAST (Enzyme-Allergo-Sorbent Test) classes of 0-6. The classes were divided into concentrations as indicated in [Table - 2].

IgE levels were determined by using an enzyme-linked fluorescent assay, reference levels being ≤120 kIU/l.

The Euroimmune system of an in vitro assay of specific IgE antibodies provides three indicator bands. Different color reactions are observed on these control bands if the incubation is performed correctly. The incubation has to be repeated with new reagents if there is no color reaction. In case of total IgE estimation, the reagent performance is first validated by a control provided with the kit. Results cannot be validated if the control values deviate from the expected values. These systems ensure the reliability of the assays performed.

Results

The age and sex distribution of 50 patients in relation to total and specific IgE is shown in [Table - 3].

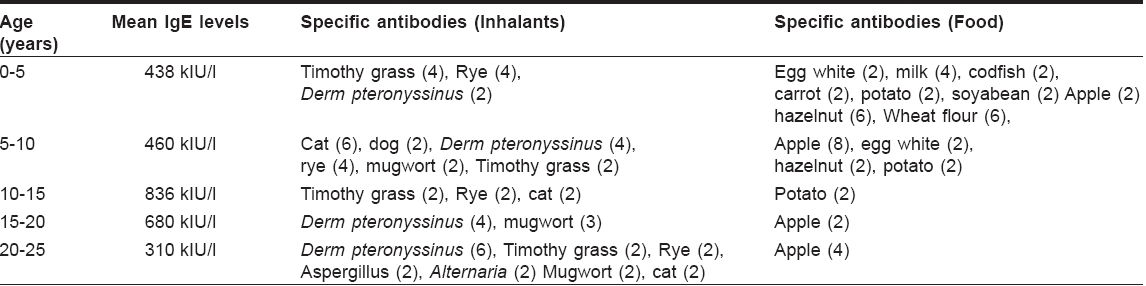

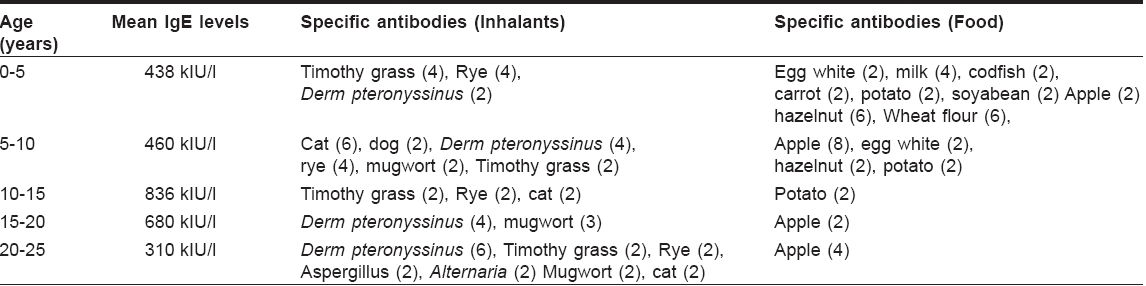

IgE was within normal limits in 6/50 patients. Mean IgE levels and the specific antibodies in the remaining group are shown in [Table - 4] (figures in the brackets showing the number of positive patients).

Eighty eight percent of patients showed elevation of IgE antibodies. The maximum elevation was observed in the 10-20 year-old age group. IgE antibodies to food substances were most common in the 0-10 years′ age group whereas antibodies to inhalants were frequently seen in the older, i.e., 10-20 years′ age group.

Discussion

The evidence for a central role for IgE was provided by several studies. [13],[14],[15],[16] These studies showed that IgE is expressed on epidermal Langerhans cells in patients of AD. Expression of the high-affinity receptor for IgE, FcR I , is significantly increased in lesional atopic skin compared with normal skin, nonlesional skin or in other diseases such as contact dermatitis, psoriasis or mycosis fungoides. [17] In atopic diseases, there is a hyperresponsiveness to a number of common environmental factors, both inhaled and ingested, which are normally tolerated by the nonatopic person. [18] Mean IgE levels in this study, were found to be maximally elevated in the age group of 10-20 years.

Burks et al . [19] studied 46 AD patients of whom 15 (33%) were found to be food allergic. Niggemann et al . [20] reported the results of 259 challenges in 107 children with AD of whom 131 (51%) were positive. Food hypersensitivity has been reported to affect 37% of children with AD from a university-based clinic in Baltimore. [21] Although results vary among studies, approximately one third of the children react positively confirming the diagnosis of food allergy. In this study, the percentage of the children (< 10 years) with specific antibodies to food allergens was found to be 65% indicating that dietary restrictions in children can play a bigger role in the treatment of AD in this population.

Among food allergens, cow′s milk, hen′s eggs, wheat, soy and peanuts are most frequently responsible for eczema or exacerbation. [22] Children with AD also have an increased incidence of hypersensitivity reactions to foods such as nuts and fish. [23] A raised specific IgE to egg has been suggested as a useful screening test in this young age group. [24],[25]

The specific antibodies to food allergens in the present series (< 10 years) were found to be against apple (10), hazelnut (8), wheat (6), egg white (4), milk (4), potato (4), carrot (2) and codfish (2), figures in the brackets indicating the number of positive hits. Apple and hazelnut were the two most common food allergens. Even in older atopics (15-25 years), specific antibodies to apple were detected in six samples, showing that apple allergy may play a role in both children and young adults.

In the very young child, either the skin prick tests or circulating specific IgE (as measured by RAST/CAP methods) may be useful as screening tests of IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity. The specific circulating titers (IgE) have been reported as being of predictive value, which could reduce the need for double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) to confirm the diagnosis. [26] If a child with AD and food allergy is put on the "correct" exclusion diet, itch lessens and the eczema can improve significantly. At best, the child can have a normal soft skin.

Clinical observations indicate that aeroallergens are relevant trigger factors in AD patients. Exacerbations of eczematous lesions after skin contact or inhalation have been described and an improvement can be observed after allergen avoidance, especially with regard to house dust mites. The most important aeroallergens in atopy are house dust, house dust mite, pollen (tree/grass/weed), animal dander (cat/dog) and molds.

The classic IgE-related tests skin prick and RAST show positive reactions in the majority of patients with AD. [27],[28] Darsow et al . showed that aeroallergens are able to elicit eczematous skin lesions in a dose-dependent way in different groups of patients with AD when applied epicutaneously on untreated skin by atopy patch tests (APT). [29] The strong correlations of APT, RAST and skin prick test in this study suggest a role of allergen-specific IgE in the development of eczematous skin lesions after aeroallergen contact. Results of the APT multicenter study [29] in Germany involving 280 AD patients showed the following positive RAST percentages: dust mite (56%), cat dander (49%), grass pollen (75%), birch pollen (65%) and mugwort pollen (53%).

The EAST positivity percentage in this study (indicating the presence of specific antibodies to various inhalants) was found to be as follows: grass pollen (44%), dust mite (32%), animal dander (24%), mugwort pollen (14%) and molds (8%). This study indicates that grass pollen and dust mite are the most common aeroallergens in Indian atopic patients. The incidence of positive reactions to inhalants increased with age as expected, and that of ingestants decreased as the age increased. The incidence of antibodies to inhalants was found to be lower when compared to the earlier study.

Patients however, in most of the cases did not come forward with any history of known allergy to the positive antigens. Limitations of this study include the small number of patients in this study. Elimination of the causal agents as detected by the specific antibodies could possibly result in improvement of AD and even maintenance of remission. Considering the high incidence of antibody positivity of 65% in children in this study, it would be worthwhile to include advice about food in patients of AD. IgE assays could also partly obviate the need for elimination diets and food challenges. Measurement of specific antibodies may therefore be a relevant tool not only in the diagnosis but also in the management of AD.

| 1. |

Marks M, Kilkenny M, Plunkett A, Merlin K. The prevalence of common skin conditions in Australian school students 2 Atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:468-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Laughter D, Istvan JA, Tofte SJ, Hanifin JM. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Oregon schoolchildren. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:649-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Yura A, Shimizu T. Trends in the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in schoolchildren: Longitudinal study in Osaka Prefecture, Japan, from 1985 to 1997. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:966-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, Andersen KE. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents, The Odense Adolescent Cohort Study on atopic diseases and dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:523-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Tay YK, Kong KH, Khoo L, Goh CL, Giam YC. The prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in Singapore school children. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:101-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Werner S, Buser K, Kapp A, Werfel T. The incidence of atopic dermatitis in school entrants is associated with individual life-style factors but not with local environmental factors in Hannover, Germany. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:95-104.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Yamada E, Vanna AT, Naspitz CK, Sole D. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): Validation of the written questionnaire (eczema component) and prevalence of atopic eczema among Brazilian children. J Invest Allergol Clin Immunol 2002;12:34-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic eczema. Acta Dermatol Venerol (Stockh) 1980;92:44-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The UK working party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis III: Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131:406-16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Bos JD, Van Leent EJ, Sillevis Smitt JH. The millennium criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 1998;7:132-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Wuthrich B, Benz A, Skvaril F. IgE and IgG4 levels in children with atopic dermatitis. Dermatologica 1983;166:229-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Friedmann PS, Holden CA. Atopic dermatitis. In : Burns DA, Breathnach SM, Cox NH, Griffiths CE, editors. Rook's Textbook of dermatology.7 th ed. Blackwell Science: 2004. p. 18.1-18.31.

th ed. Blackwell Science: 2004. p. 18.1-18.31.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Bruynzeel-Koomen C, van Wichen DF, Toonstra J, Berrens L, Bruynzeel PL. The presence of IgE molecules on epidermal Langerhans' cells in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res 1986;278:199-205.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Bieber T, Rieger A, Neuchrist C, Prinz JC, Rieber EP, Boltz-Nitulescu G, et al . Induction of FCeR2/CD23 on human epidermal Langerhans' cells by human recombinant IL4 and IFN. J Exp Med 1989;170:309-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Bieber T, de la Salle C, Wollenberg A, Hakimi J, Chizzonite R, Ring J, et al . Constitutive expression of the high affinity receptor for IgE (FCeR1) on human Langerhans' cells. J Exp Med 1992;175:1285-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Maurer D, Ebner C, Reininger B, Fiebiger E, Kraft D, Kinet JP, et al . The high affinity IgE receptor mediates IgE-dependent allergen presentation. J Immunol 1995;154:6285-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Wollenberg A, Wen S, Bieber T. Langerhans' cells phenotyping: A new tool for differential diagnosis of inflammatory skin diseases. Lancet 1997;346:1626-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Lever R. The role of food in atopic eczema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:S57-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Burks AW, Mallory SB, Williams LW, Shirrell MA. Atopic dermatitis: clinical relevance of food hypersensitivity reactions. J Pediatr 1988;113:447-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Niggemann B, Sielaff B, Beyer K, Binder C, Wahn U. Outcome of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge tests in 107 children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy 1999;29:91-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics 1998;101:e8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Darsow U, L�bbe J, Taοeb A, Seidenari S, Wollenberg A, Calza AM, et al . Position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19:286-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 1: Immunopathogenesis and clinical disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:717-28.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Bock SA, Atkins FM. Patterns of food hypersensitivity during sixteen years of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges. J Pediatr 1990;117:561-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Lever R, MacDonald C, Waugh P, Aitchison T. Randomised controlled trial of advice on an egg exclusion diet in young children with atopic eczema and sensitivity to eggs. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1998;9:13-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Sampson H, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;100:444-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Ring J, Darsow U, Abeck D. The atopy patch test as a method of studying aeroallergens as triggering factors of atopic eczema. Dermatol Treatment 1996;1:51-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Darsow U, Vieluf D, Ring J. Atopy patch test with different vehicles and allergen concentrations: An approach to standardization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:677-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Darsow U, Vieluf D, Ring J. Evaluating the relevance of aeroallergen sensitization in atopic eczema with the atopy patch test: A randomized, double-blind multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:187-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,138

PDF downloads

2,221