Translate this page into:

Acitretin

Correspondence Address:

Balkrishna P Nikam

Department of Dermatology, TN Medical College and BYL Nair Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Nikam BP, Amladi S, Wadhwa S L. Acitretin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:167-172 |

|

|

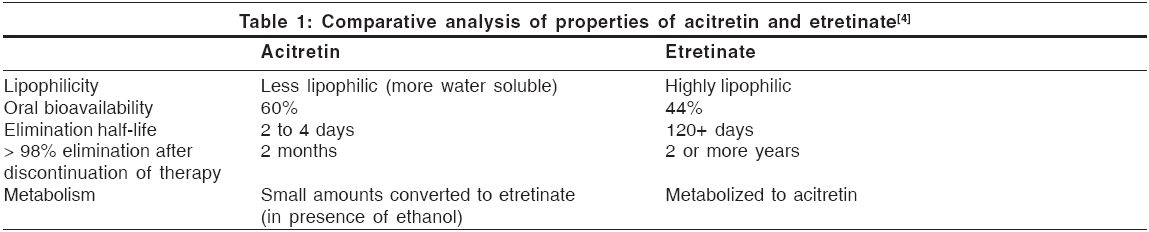

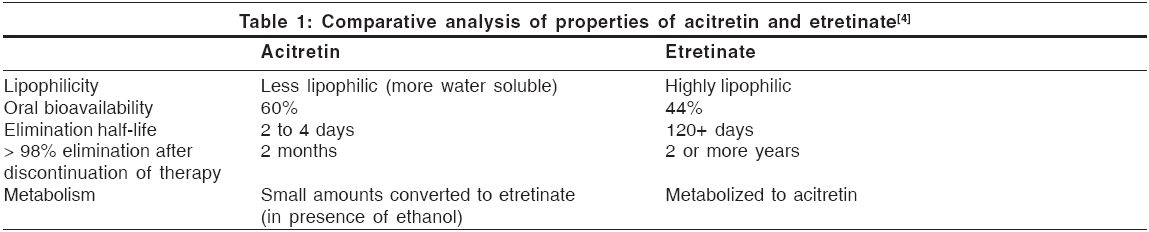

Isotretinoin, a first generation retinoid, was first synthesized in 1955 and its efficacy in treatment of acne and keratinization disorder was studied in 1971. Subsequently, it was confirmed to be highly effective for acne vulgaris and cystic conglobate acne and was approved as a modality of therapy in the treatment of severe nodulocystic acne in 1982.[1] The aromatic retinoids (second generation) were developed because they appeared to be more effective in treating psoriasis and other keratinizing disorders. After more than a decade of research, in 1986, etretinate was approved for the treatment of psoriasis, but problems with its safety related to teratogenicity and long-term storage in fat led to its replacement with acitretin in 1998, a free acid of etretinate.[1]

With its more favorable pharmacokinetics, including a significantly shorter elimination half-life, acitretin has become the retinoid of choice in treatment of psoriasis, replacing etretinate.

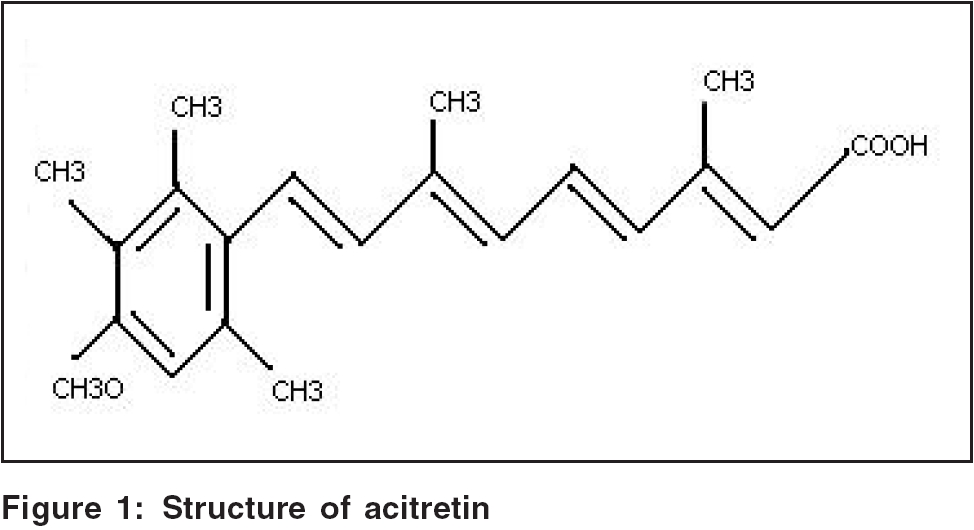

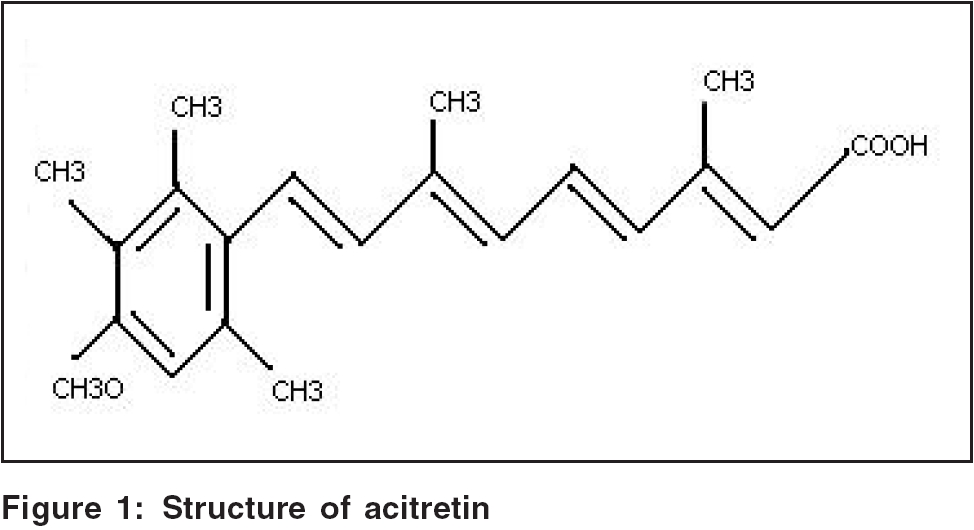

Structure [Figure - 1][2]

The structure is described in [Figure - 1].

Pharmacokinetics [Table - 1][1],[4]

Acitretin is rapidly and extensively distributed throughout the body without unexpected accumulation in any tissue. It is extensively bound to plasma proteins (95%).

The metabolism of acitretin occurs mainly in the liver. The major metabolite of acitretin is its 13 - cis - isoacitretin. A small amount of acitretin is converted into etretinate, which is more lipid-soluble and persists for much longer time in the fatty tissues. An enzyme present in hepatic post-mitochondrial supernatant fraction catalyzes this reaction. The reaction is enhanced, both in vivo and in vitro, by ethanol.[5] This has created concern that birth defects might result if acitretin-treated women inadvertently ingest alcohol, which is commonly used in cough syrup, over-the-counter medications and cooking ingredients. Because of this knowledge, the recommended period for contraception after acitretin therapy has been lengthened from 2 months to 2 years.[5]

Upto 50% of a dose is excreted in urine and up to 60% in the feces. Following chronic administration of the drug, elimination appears to be bi-exponential, with a half-life of the initial phase approximately 50 h.

Mechanism of action

It is hypothesized that acitretin is metabolized to molecules that bind to RARs. Transactivation of RAR causes direct effects on gene transcription mediated through retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) and indirect effects by down-regulating certain genes that do not have RARE, thus inducing negative effect on gene transcription leading to anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects.[6]

Anti-psoriatic activity[5]

1. Antikeratinizing effects

a. induce differentiation and reduce hyperplasia and normalize accelerated epidermopoiesis.

2. Anti-inflammatory effect

a. reduces release of leucotrienes and dihydroeicosatetraenoic acid products and inhibits of neutrophil chemotaxis.

b. interferes with the esterification and incorporation of arachidonic acid into nonphosphorus lipids in human keratinocytes and hence reduces inflammation in psoriatic plaques.

c. Inhibition of ornithine decarboxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in biosynthesis of polyamines, lessens the inflammatory hyperplasia.

3. Anti-proliferative effect

a. Concentration dependent inhibition of cell growth and potentiates epidermal growth factor induced inhibition of cell proliferation.

b. Acitretin increases the level and activity of AMP-dependent protein kinases where they were deficient in human psoriatic fibroblasts, leading to increase in the growth-inhibitory effect of cAMP in fibroblast.

Other effects

1. Anti-neoplastic effect: Mechanism is far from clear. Acitretin inhibits the invasiveness and metastatic potential of the adenocarcinoma cells.

2. Effects on embryogenesis and morphogenesis: Retinoids participate in the formation of diverse embryonic structures (face, heart, eye, limb and nervous system).

3. Effects on intercellular matrix components: At physiologic concentrations, there is an increase in mucopolysaccharides, collagen and fibronectin synthesis and a decrease in collagenase production. At nonphysiologic concentrations, retinoids inhibit the proliferation of human fibroblasts and synthesis of collagen type III and I and thus interfere with wound healing.[7]

4. Anti-acne and sebum effects: First-generation retinoids and acitretin inhibit sebocyte proliferation in a dose and time dependent manner. Isotretinoin is the most potent inhibitor of lipid synthesis (48.2% reduction), followed by tretinoin (38.6% reduction) and then by acitretin (27.5% reduction).

Uses

Generalized pustular psoriasis

Analysis of 385 patients of generalized pustular psoriasis reveals that retinoid therapy is effective in 84% of patients, methotrexate in 76% of patients, cyclosporine in 71% of patients. Thus, retinoid is the choice of drug in generalized pustular psoriasis.[8]

Erythrodermic psoriasis

As monotherapy, acitretin has been shown to be effective in treating erythrodermic psoriasis.[9]

Severe plaque type psoriasis Monotherapy with acitretin for plaque-type psoriasis is often less successful; however, its use in combination with other therapies is highly effective in treating this form of the disease.[10]

Psoriasis associated with HIV infection Acitretin does not appear to have immunosuppressive properties[12] and hence is preferred for this indication.

Therapeutic efficacy has been assessed using acitretin as monotherapy and in combination therapy with PUVA and UVB irradiation as well as in comparisons with etretinate. An overall evaluation of clinical experience in 635 patients with various dermatoses from main 12 trials has indicated a marked improvement, good or very good response, including complete remission, in 78% of patients after treatment with acitretin, while 8.5% showed no change or had a poor response. (Geiger and Czarnetzki, 1988)

Other uses

Disorders of keratinization: Darier′s disease, ichthyosis, keratodermas

Inflammatory dermatoses: Lupus erythematosus, lichen sclerosus et atrophicans, lichen planus (oral erosive, palmoplantar), graft versus host disease

Prophylactic: Prevention of cutaneous malignancies in solar-damaged skin and in genetic syndromes predisposing to skin cancer

Contraindications

Acitretin is absolutely contraindicated in the female patients who are pregnant or want to become pregnant in near future and relatively contraindicated in patients having significant systemic disease and severe lipid derangements.

High risk groups[2]a. Neonates: Contraindicated in neonates unless the condition is life threatening (harlequin fetus)

b. Children: Prolonged therapy requires monitoring of bone structures and should be used in exceptional circumstances

c. Elderly: Incidence of adverse events appear to be higher

d. Concurrent diseases: Require frequent monitoring

Dosage

Response to acitretin has been shown to be dose dependent, with higher doses yielding greater improvement and more frequent clearance of psoriatic lesions. Adverse effects are also dose dependent and can be dose-limiting, preventing use of higher, more effective doses of acitretin in many patients.[4]

Optimal dose range for monotherapy is 25 to 50 mg/day.[12] Improvement occurs gradually, requiring up to 3-6 months for peak response. Higher doses (50-75 mg/day) result in more rapid and possibly more complete, responses but are associated with significantly increased side effects.

Acitretin monotherapy is most effective for pustular and erythrodermic types of psoriasis.[9] Combination regimens are generally preferred for plaque-type psoriasis.

Unlike isotretinoin or etretinate, dosing of acitretin is not based on body weight.

Dose escalation

Dose escalation is the optimal strategy for dosing acitretin in individual patients. Advantages of this regimen include allowing gradual onset of ′tolerance′ to side effects of retinoid therapy and avoiding use of higher doses than needed for effective response in an individual patient. As some patients are exquisitely retinoid-responsive, initiating treatment at higher doses will lead to unnecessarily aggressive treatment in these patients. Based on results of dose-ranging studies previously described, 25 mg/day appears to be a reasonable starting dose for a dose-escalation protocol.[12]

Maintanence dose

Most patients actually suffer relapse within 2-6 months after discontinuing acitretin, so maintenance therapy is required. Recommended dose is 20 to 50 mg daily and after satisfactory response, dose can be reduced to as low as 10 to 25 mg daily or 25 mg every other day for long-term maintenance therapy.

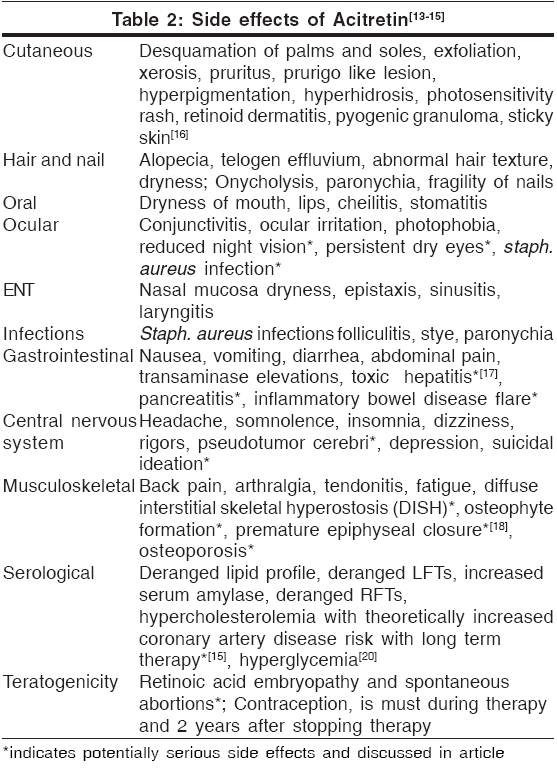

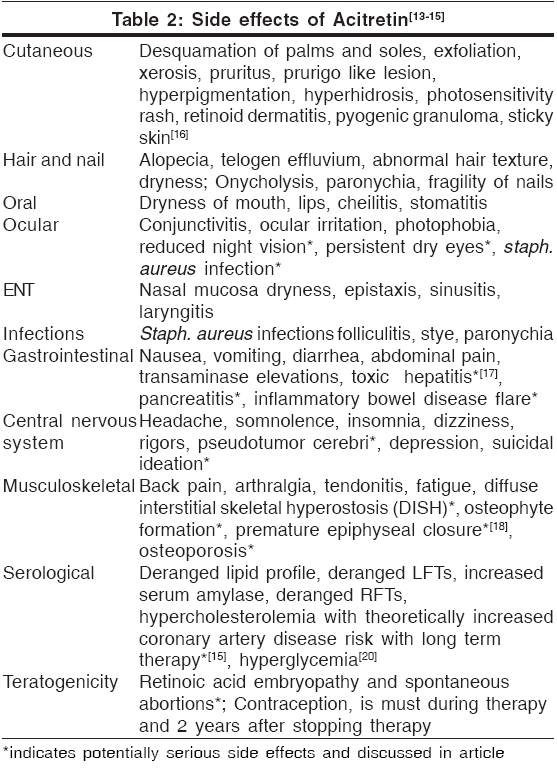

Side effects[Table - 2]

Teratogenicity[13]

There is no safe minimal dose of acitretin for use during pregnancy. To date, of the six known fetal outcomes associated with acitretin use during pregnancy, two had malformations consistent with retinoid embryopathy.

Contraception is recommended for all female patients of childbearing potential 1 month before beginning acitretin therapy, during active therapy and 3 years after therapy as described above. Because there is inadequate study of retinoids in semen and subsequent transfer to the female, it is not known whether retinoids present in semen pose a risk to the developing fetus. To date, seven pregnancies have been reported to be associated with acitretin therapy in the male at time of conception. None of these resulted in malformations typical of retinoid embryopathy. However, no conclusions can be made from this very limited data. It is not known whether acitretin in seminal fluid poses risk to a developing fetus.[14]

Hepatotoxicity[17]

Use of acitretin may cause transient and reversible elevations in serum liver enzymes. Severe hepatotoxic reactions resulting from retinoid use are rare and idiosyncratic. Data from 1877 patients receiving acitretin therapy showed overt chemical hepatitis in only 0.26%. In an open-label study evaluating hepatotoxicity by pre- and post-treatment liver biopsies, 83% of 128 patients receiving acitretin demonstrated improvement or no deterioration in terms of liver pathology during the course of treatment. It is recommended to do routine monitoring of liver function more frequently in alcoholics, diabetics, obese individuals; and if possible, concurrent use of hepatotoxic agents should be avoided.

Retinoid therapy may cause changes in the serum lipid profile resulting in hyperlipidemia in some patients. In 525 patients receiving acitretin therapy in clinical trials with doses ranging from 10 to 75 mg/day, increases in triglyceride levels occurred in 66% and increases in total cholesterol occurred in 33% of patients. In addition, levels of HDL decreased in approximately 40% of patients. Lipid abnormalities may be managed by reducing the dose of acitretin, making appropriate dietary changes, or by means of lipid-lowering medications as needed. Lipid levels normalize in most patients after discontinuation of retinoid therapy.

Increases of serum triglycerides to levels associated with pancreatitis are not common, although a case of fatal fulminant pancreatitis has occurred. Patients at high risk include those with diabetes mellitus, obesity, increased alcohol intake, or a family history of hypertriglyceridemia. Patients should be advised to promptly report any significant acute abdominal symptoms such as severe pain or emesis.

Pseudotumor cerebri

Pseudotumor cerebri, or benign intracranial hypertension, has occurred in very rare cases with use of systemic retinoids including acitretin. This effect has been associated with concurrent tetracycline or minocycline administration.[15] In the single reported case of pseudotumor cerebri occurring in a patient receiving acitretin, however, neither tetracycline nor minocycline was involved. If a patient receiving acitretin complains of headache, visual changes, nausea, or vomiting, examination for papilledema should be performed immediately. Treatment should be discontinued and the patient should be referred for appropriate care.

Hyperostosis

Studies[18] examining effects of retinoids (etretinate and acitretin) on bone have shown that retinoid effects on bone, if present at all, likely involve worsening of pre-existing skeletal overgrowth rather than de novo changes. Induction of new bony abnormalities occurred in fewer than 1% of patients.[19]

In light of these results, a screening radiograph of an ankle to document pretreatment bony status has been suggested. Because the frequency and severity of iatrogenic bony abnormalities in adults is low, routine annual radiography is not warranted unless indicated by the presence of symptoms or long-term use of high dose acitretin.

Mucocutaneous side effects

In an analysis of 176 patients receiving acitretin in clinical trials at the standard recommended doses of 25 to 50 mg/day, cheilitis occurred in approximately 60 to 75%, skin peeling in 25 to 50%, rhinitis in 20 to 30%, dry skin in 15 to 25% and hair loss in 10 to 25%. Other effects such as sticky skin, rigors, itchiness and dry mouth were less common, occurring in fewer than 25% of patients, even those receiving the highest doses. Many of these mucocutaneous side effects can be treated symptomatically, for example, with emollients for dry skin or lips. Some of these effects, particularly hair loss, however, may be distressing to patients. Patients should therefore be maintained on the lowest effective acitretin dose of 25 to 50 mg/day to minimize the occurrence of these side effects.

Drug interactions[21]

Concurrent use of retinoids with other therapies having similar side effects may increase the risk of these adverse events. As mentioned above, tetracycline (increased photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri), minocycline (pseudotumor cerebri), alcohol (increased conversion to etretinate, hepatotoxicity) and other retinoids or vitamin A supplements in excess of minimal daily requirements (hypervitaminosis) should be avoided. Other therapeutic agents that may interact with acitretin and should be monitored carefully include antidiabetic agents (alterations in blood glucose), corticosteroids (hyperlipidemia, pseudotumor cerebri) and methotrexate (increased methotrexate level, hepatotoxicity). In addition, acitretin has been shown to possibly interfere with the contraceptive effect of microdose progestin ("minipill") preparations and in one patient was associated with a significant increase in serum progesterone, necessitating withdrawal of acitretin therapy. However, in the same analysis, acitretin was shown not to interfere with the antiovulatory effect of estrogen-progesterone combinations even after a prolonged period of intake. Unsupervised excessive exposure to sunlight or sun lamps should be avoided because of increased photosensitivity during retinoid therapy.

Conclusion

Acitretin has been found to be effective in psoriasis and some keratinization disorders. Despite being associated with a wide range of side effects, the benefits of its use scores over the side effects. Monitoring of lipid profile and liver function test is necessary, more frequently in high-risk patients as mentioned above. Teratogenicity is a serious concern and extreme precautions should be taken while prescribing acitretin to females of reproductive age group.

| 1. |

Nguyen EH, Wolverton S. Systemic retinoids. In : Wolverton S, editors. Textbook of comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy. WB Saunders Co: Philadelphia; 2001. p. 269-302.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Acitretin package insert. Nutley NJ, Roche laboratories. 1997.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wiegand UW, Chou RC. Pharmacokinetics of acitretin and etretinate. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:S25-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Pilkigton T, Brogden RN. Acitretin: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use. Drugs 1992;43:597-627.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Koo J, Nguyen Q, Gambla C. Advances in psoriasis therapy. Adv Dermatol 1997;12:47-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Chandraratna RA. Rational design of receptor- selective retinoids. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:S124-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Hein R, Mensing H, Muller PK, Braun-Falco O, Krieg T. Effect of vitamin A and its derivatives on collagen production and chemotactic response of fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol 1984;111:37-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Lassus A, Geiger JM. Acitretin and etretinate in the treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis: A double blind comparative trial. Br J Dermatol 1988;119:755-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Gollnick H, Bauer R, Brindley C, Orfanos CE, Plewig G, Wokalek H, et al. Acitretin versus etretinate in psoriasis: Clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a German multicentre study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;19:458-69.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Geiger J, Saurat JH. Acitretin and etretinate: How and when they should be used. Dermatol Clin 1993;11:117-29.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Buccheri L, Katchen BR, Karter AJ, Cohen SR. Acitretin therapy is effective for psoriasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:711-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Ling MR. Acitretin: Optimal dosing strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:S13-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Saurat JH. Side effects of systemic retinoids and their clinical management. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:S23-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Ratz HI, Waalen J, Leach EE. Acitretin in psoriasis: An overview of adverse effects. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:S7-S12

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Gupta AK, Goldfarb MT, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ. Side-effect profile of acitretin therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20:1088-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Lebwohl M, Ali S. Treatment of psoriasis. Part 2. Systemic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:649-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Roenigk Jr. HH, Callen JP, Guzzo CA, Katz HI, Lowe N, et al. Effects of acitretin on the liver. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:584-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

McGuire J, Lawson JP. Skeletal changes associated with chronic Isotretinoin and etretinate administration. Dermatologica 1987;175:S169-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

van Dooren-Greebe RJ, Lemmens JA, De Boo T, Hangx NM, Kuijpers AL, van de Kerkhof PC. Prolonged treatment with oral retinoids in adults: No influence on the frequency and severity of spinal abnormalities. Br J Dermatol 1996;134:71-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Singh PK, Kumar P. Acitretin induced reversible hyperglycemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:183-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Anderson WK, Feingold DS. Adverse drug interactions clinically important for dermatologist. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:468-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

8,378

PDF downloads

3,095