Translate this page into:

Antiphospholipid antibodies in a patient of Lucio phenomenon presenting with the gangrene of digits

Corresponding author: Dr. Jignaben Krunal Padhiyar, Room No. 35, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, GCS Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Ahmedabad - 25, Gujarat, India. dr.jignapadhiyar@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Patel NH, Padhiyar JK, Patel T, Patel A, Chhibber A, Raval R, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies in a patient of Lucio phenomenon presenting with the gangrene of digits. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:97-101.

Sir,

Lucio leprosy is a diffuse form of lepromatous leprosy, commonly seen in Mexico and Costa Rica, not infrequent in the Gulf Coast, but quite rare in the rest of the world.1 Lucio leprosy presents as a slowly progressive, diffuse infiltration of the skin of the face and most of the body without any previous evidence of discrete lesions. The disease is often unmasked by a specific severe reaction state, the Lucio phenomenon— presenting clinically as multiple, well-defined, angular jagged purpuric lesions evolving into massive ulcerations. The antiphospholipid antibodies were originally detected and used by Wasserman for the diagnosis of syphilis. It was subsequently found that antiphospholipid antibodies are not only specific for syphilis but are also found in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and with other infections.2 Here we present a case of Lucio phenomenon in a patient of Lucio leprosy with positive antiphospholipid antibodies presenting with digital gangrene.

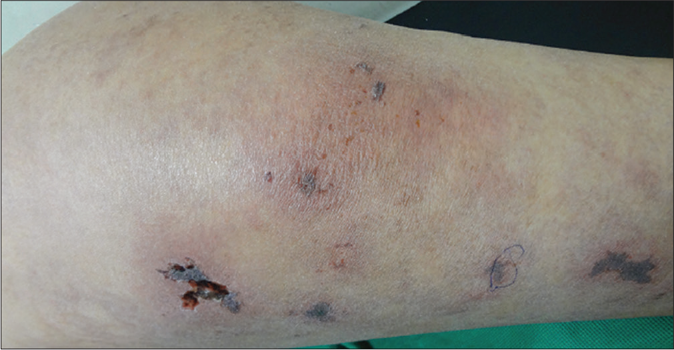

A 45-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department for sudden blackening of toes and fingers for 6 days along with fever and arthralgia for the last 8 days. There was no clinically relevant significant past, personal and obstetric history. Menstrual history was unremarkable. Systemic examination was normal except for mild splenomegaly. Bilateral pitting edema was present with tense, dry, xerotic skin of both the lower limbs. Blackish discoloration of the left 3rd, 4th, 5th toes, right great toe and right 3rd,4th 5th toes extending from the tip of toes to metatarsophalangeal joints, with similar blackish discoloration of the right ring finger extending from tip of the finger to distal interphalangeal joint on the palmar aspect of the hand were seen. Affected areas were hard, non-tender and cold on palpation, suggesting established gangrene. Multiple livedo racemosa-like lesions were present involving the bilateral lower limb and trunk. Multiple angulated purpuric necrotic lesions with surrounding ill-defined erythema were present on the left thigh with one lesion showing ulcerative changes. The patient had diffuse erythema of face with difficult to pinch tense shiny skin with complete loss of bilateral eyebrows and eyelashes. There was no infiltration of the ear lobes [Figure 1a-c].

- Erythematous shiny facial skin with the complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows

- Multiple angulated necrotic lesions with ulceration

- Gangrene involving multiple toes

Bilateral infraorbital, left ulnar, bilateral radial, left common peroneal and left posterior tibial nerves were thickened and tender. Temperature sensations were impaired on the face and were completely absent in all limbs. Fine touch sensation was lost in the dorsal aspect of bilateral hands and lower limbs. Arterial pulses were palpable and normal in all the limbs.

Relevant laboratory and radiological investigations are mentioned in Table 1.

| Investigation | Patient value |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 11.5 g/dL |

| Total leukocyte count | 14400/mm3 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 32 mm/h |

| Prothrombin time | P=14.8, C-12.8 INR-1.16 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | P=31.5, C-29.6 s |

| Random blood sugar | 120 mg/dL |

| Serological screening for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, ANA, ANCA, RA factor | Negative |

| 24-h urine protein excretion | 841 mg/24 h |

| D-dimer | 800 mg/mL |

| aPL | IgG=48.3 GPL U/mL (0-10) |

| IgM=156 MPL U/mL (0-10) | |

| aCL | IgG=56.6 GPL (>15 positive) |

| IgM=>255 MPL (>15 positive) | |

| ẞ2GPI | IgG=3.0 U/mL (>16 positive) |

| IgM=>100 U/mL (>16 positive) | |

| DRVVT screen (LA1) | 85.9 s (31-33 s) |

| DRVVT confirm (LA2) | 48.6 s (31-33 s) |

| DRVVT mixing (1:1 with PNP) | 51.3 s (31-33 s) |

| DRVVT confirm (LA1/LA2) | 1.77 s (0.8-1.2 s) |

| APTT screen | 54.4 S (31.4-43.4 s) |

| APTT mixing | 40.1 s (31.4-43.4 s) |

| X-ray chest, ECG, echocardiography, arterial and venous Doppler study ofextremities | No abnormality detected |

| Pulmonary and brain CT angiography study | No abnormality detected |

ANA=antinuclear antibodies, ANCA=antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies, DRVVT=diluted Russel viper venom test, APTT=activated partial thromboplastin time, ECG=electrocardiogram, CT=computed tomography, RA=rheumatoid arthritis, aPL=antiphospholipid antibodies, aCL=anticardiolipn, ẞ2GPI=beta-2 glycoprotein 1, IgG=immunoglobulin G, IgM=immunoglobulin M,

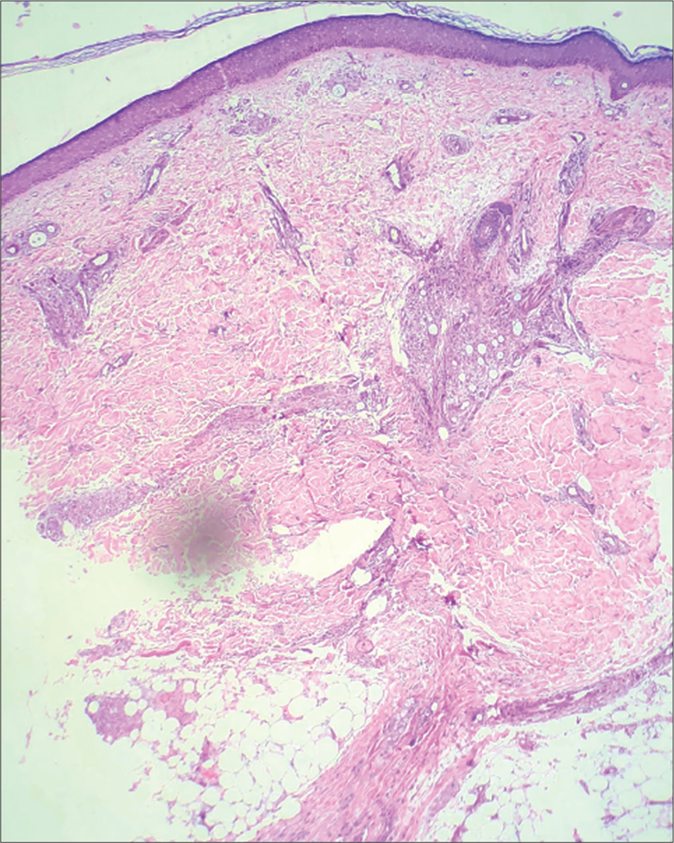

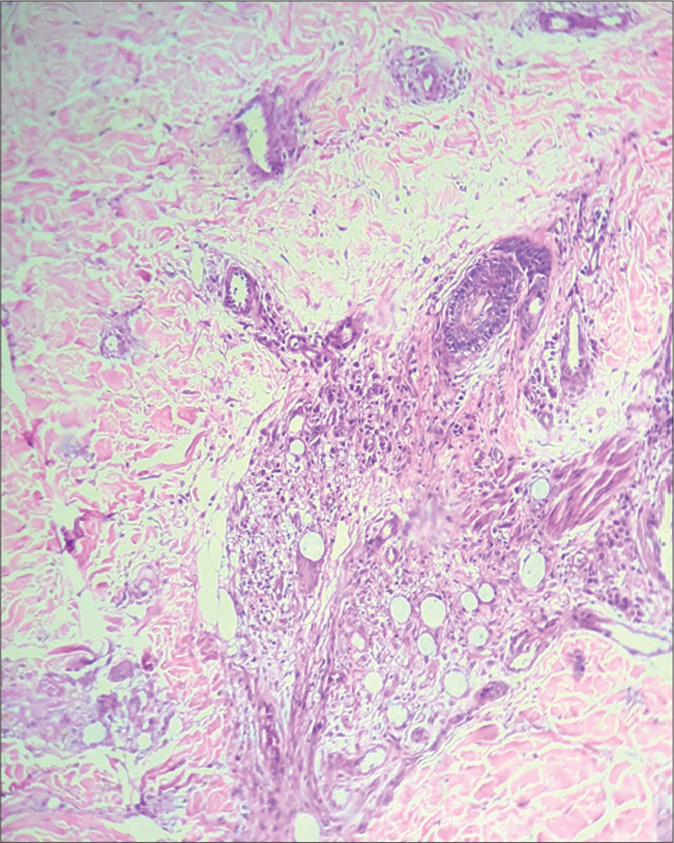

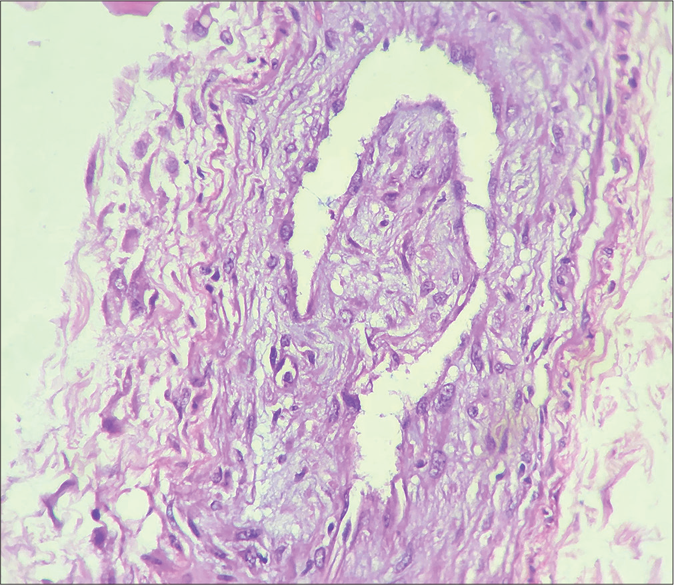

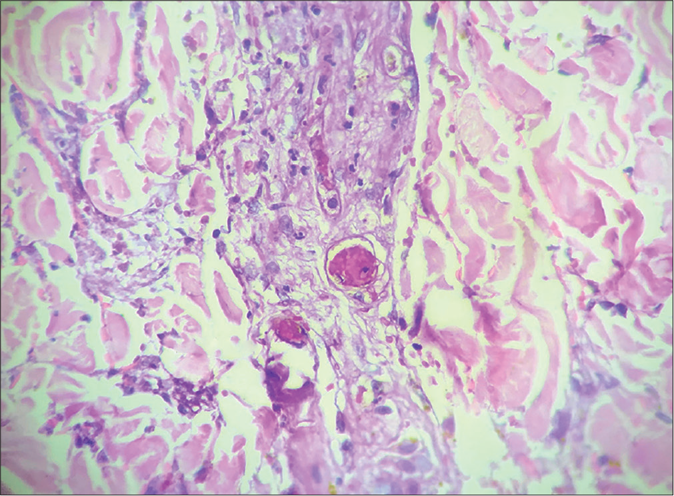

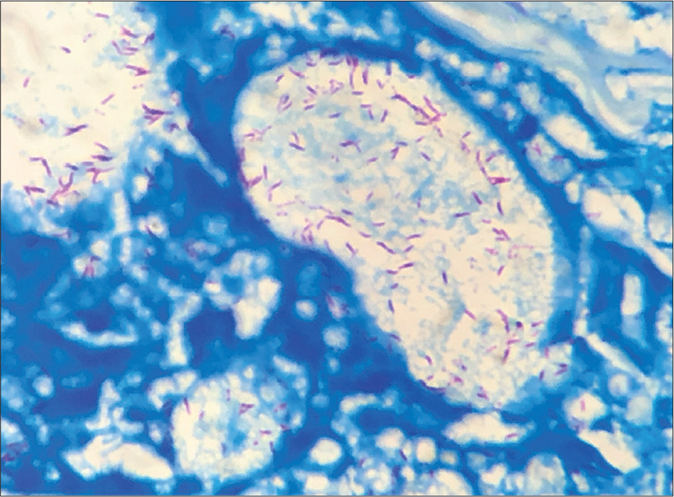

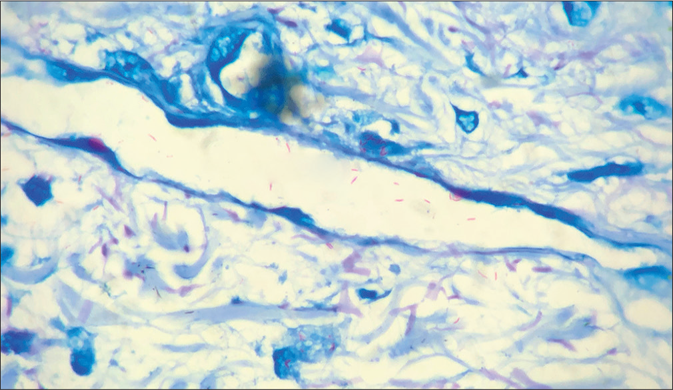

Slit-skin smear examination from earlobes, eyebrows, normal looking skin of cheek and scraping from nasal mucosa revealed 90% solid staining acid-fast bacilli with globi formation and mean bacterial index of 4+. Polymerase chain reaction study from skin biopsy isolated Mycobacterium leprae. Histopathological examination of a skin biopsy from the ulcer and from adjacent normal skin showed perineural and periadnexal foamy macrophages and Virchow’s cell with numerous bacilli; multiple superficial vessels showing signs of vasculitis, mild lobular panniculitis, a large subcutaneous vessel invaded by foamy macrophages and the presence of lepra bacilli in endothelial cells as well as in the lumen (characteristic of Lucio phenomenon). Multiple vessels in mid dermis showing the presence of thrombi in the absence of signs of vasculitis typical of occlusive vasculopathy were seen [Figures 2a-c and 3a-c].

- Biopsy from normal-appearing skin on thigh showing atrophic epidermis with periappendageal and perineural infiltrate (H&E, ×40)

- Periappendageal and perineural infiltrate of foamy macrophages and Virchow’s cells. (H&E, ×100)

- Infiltrate of foamy macrophages invading medium-size vessel (H&E, ×400)

- Vessels in mid dermis showing thrombosis without signs of vasculitis (H&E, ×400)

- Presence of lepra bacilli in Virchow’s Cell (Fite Faraco stain, ×1000)

- Lepra bacilli invading vessel wall and vascular lumen (Fite Faraco stain, ×1000)

The case was diagnosed as Lucio leprosy with Lucio phenomena having antiphospholipid antibodies. Standard anti-leprosy treatment recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) containing multidrug therapy of rifampicin, clofazimine and dapsone was initiated with oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg) for Lucio phenomenon. Low-molecular-weight heparin 60 mg subcutaneous once a day for 7 days was added and transitioned to oral warfarin keeping international normalization ratio between 2 and 3. At the time of submission of this report, the patient was on regular follow-up with complete resolution of ulcer and gangrene in all digits except the left fifth toe [Figure 4].

- Complete resolution of gangrenous changes except left fifth toe (autoamputation) at 4-month follow-up

Our patient had non-nodular diffuse infiltration of skin with complete loss of eyebrows and eyelashes and shiny skin of face characteristic of Lucio-Latapi leprosy. Lucio phenomenon can be the initial presentation of the disease, presenting as widespread necrotic ulcerations.3 Necrotic lesions of Lucio phenomenon can mimic cutaneous small or mixed vessel vasculitis clinically, which was true for our patient too. Livedo racemosa-like lesions and gangrene involving multiple digits, in this case, can be attributed to the thrombotic vasculopathy of antiphospholipid syndrome. Histologically, the Lucio phenomenon shows necrotizing panvasculitis with vascular proliferation and the presence of angio-invasion by lepra bacilli as was observed in our patient. A study from Mexico where Lucio leprosy is more prevalent, reported Mycobacterium Lepromatosis being isolated from such patients.4 Polymerase chain reaction study from our patient isolated M. Leprae from the skin specimen. Previously, it was postulated that antiphospholipid antibodies associated with infections do not possess anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I (anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I) activity, therefore, are not associated with thrombosis.5 de Larrañaga et al found 56.8% patients of leprosy have beta-2 glycoprotein I (majority of immunoglobulin M class) activity without any symptoms, whereas another study found increased levels of anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I antibodies in significant proportion in patients of leprosy and its association with thrombosis.6,7 Our patient, too, had an immunoglobulin M antibody to beta-2 glycoprotein with symptomatic thrombosis of digital arteries. Nunzie et al. and Wallin et al have reported similar cases of Lucio phenomenon with antiphospholipid syndrome.8,9 Noteworthy is the fact that thromboembolic phenomenon is also a well-documented adverse event of thalidomide.10 Our patient was not on any medication at the time of the presentation. Our case highlights the fact that Lucio leprosy and Lucio phenomenon are possible clinical presentations in Indian patients too.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal the identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Case definition and clinical types of leprosy In: Kumar B, Kumar H, eds. IAL Textbook of Leprosy (2nd ed). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2016. p. :236-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:388-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffuse necrotic ulcerations revealing lepromatous leprosy with Lucio's phenomenon. Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;2:136.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The leprosy agents Mycobacterium lepromatosis and Mycobacterium leprae in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:952-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A phospholipid-beta 2-glycoprotein I complex is an antigen for anticardiolipin antibodies occurring in autoimmune disease but not with infection. Lupus. 1992;1:75-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: Evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beta2-Glycoprotein I-dependent anticardiolipin antibodies as risk factor for reactions in borderline leprosy patients. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:387-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucio leprosy with Lucio's phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leprosy, antiphospholipid antibodies and bilateral fibular arteries obstruction. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2009;49:181-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ENLIST 1: An International multi-centre cross-sectional study of the clinical features of erythema nodosum leprosum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004065.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]