Translate this page into:

Ashy dermatosis, lichen planus pigmentosus and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis: Are we splitting the hair?

Correspondence Address:

Vinod Kumar Sharma

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi - 110 029

India

| How to cite this article: Gupta V, Sharma VK. Ashy dermatosis, lichen planus pigmentosus and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis: Are we splitting the hair?. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84:470-474 |

Sir,

What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet

-William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

The first description of ashy dermatosis is credited to Ramirez of El Salvador in 1957 who termed these patients Los cenicientos, meaning the ashen ones.[1] It was later called “erythema dyschromicum perstans” to highlight the erythematous halo around pigmented macules.[2] In the 1970s, Bhutani et al. gave a detailed account of a similar disease presenting as brown-to-slate-gray macules on the face, trunk and flexures of Indian patients. The histopathology showed pigment incontinence, accompanied by interface dermatitis in some cases. It was considered a macular variant of lichen planus and was termed “lichen planus pigmentosus.”[3] Around the same time, another pigmentary disorder was described in Japan by Nakayama et al. by the name of “pigmented cosmetic dermatitis,” now also known as Riehl's melanosis, and cosmetic allergens were implicated in causing the pigmentation.[4] Ever since, existence of these disorders as distinct entities or as variants of the same disease has been a topic of incessant debate.

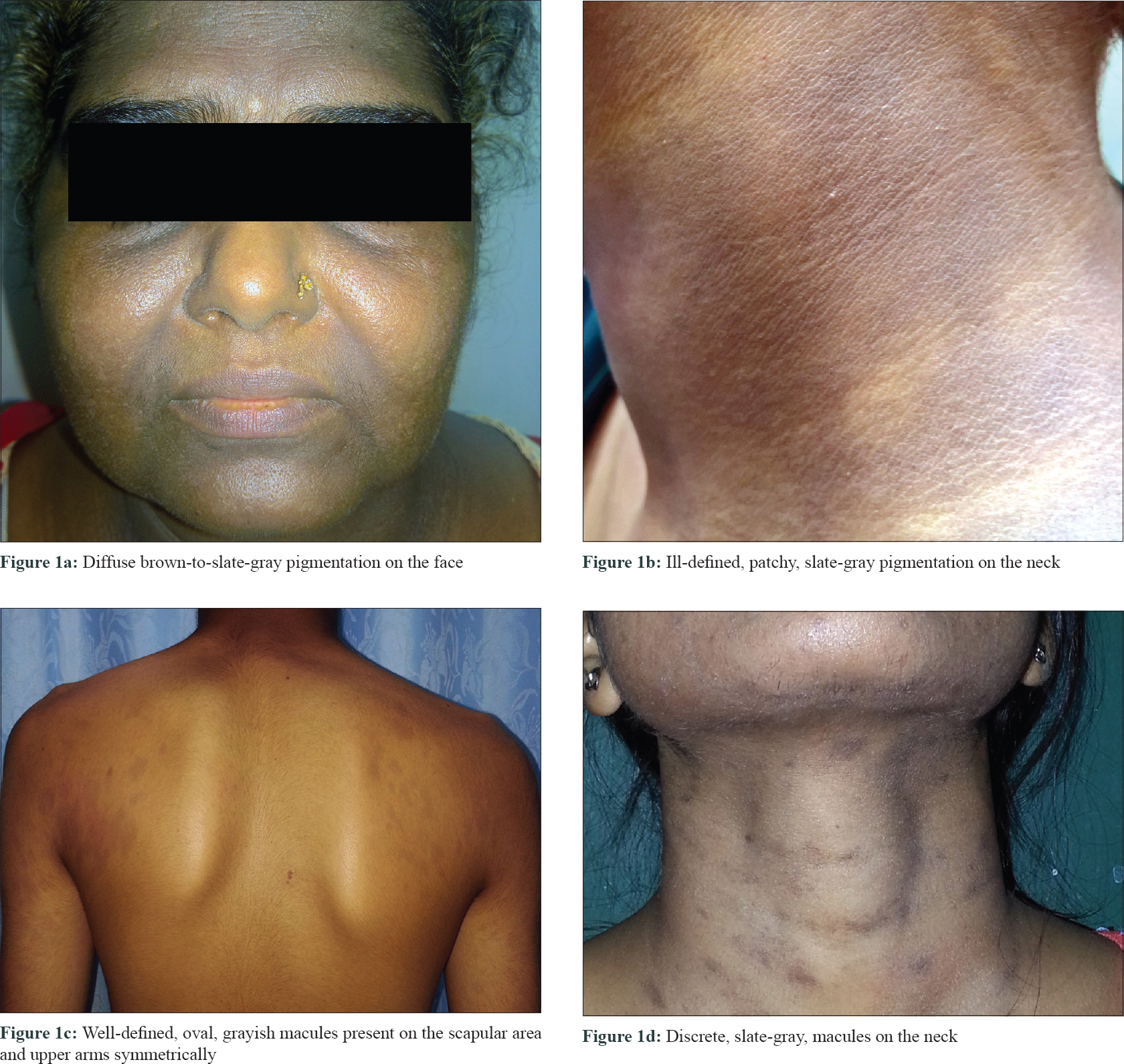

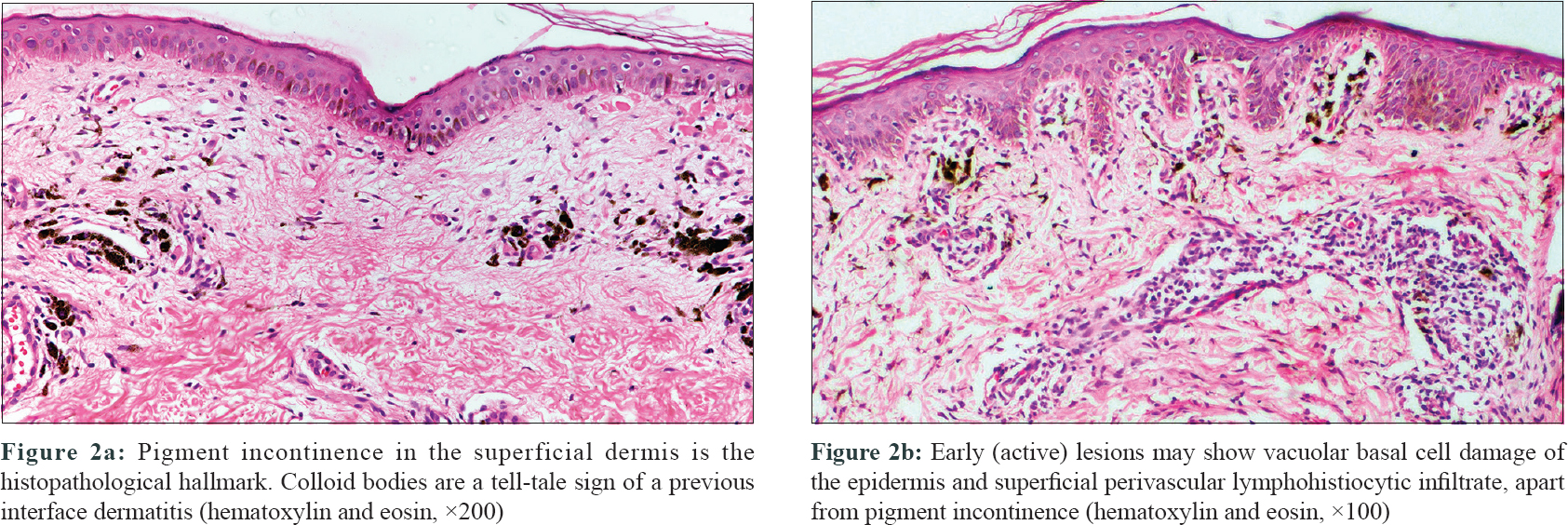

All three entities share several features – varying shades of brown-to-slate-gray macular hyperpigmentation without antecedent inflammatory lesions on the face, trunk and upper limbs [Figure - 1]; and thinned epidermis, pigment incontinence and basal cell vacuolization on histopathology [Figure - 2]. Even the patient profile is similar – young-to-middle-aged females with dark skin complexion are preferentially affected. Bhutani considered ashy dermatosis and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis to be the same disease as lichen planus pigmentosus, but this view is not shared by all.[5],[6]

|

| Figure 1: |

|

| Figure 2: |

In a clinicopathological study of ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus, patients with ashy dermatosis (n = 20) were described as having symmetrical asymptomatic blue-gray macules with an erythematous border, where as patients with lichen planus pigmentosus (n = 11) had pruritic, darker macules without the active red border. Histological differences were not significant.[7] Notably the erythematous halo, described as a characteristic feature of ashy dermatosis and the primary differentiating feature, was absent in 60% of patients with ashy dermatosis. Further, the authors do not state what “gold standard” was used to reliably distinguish between these two largely overlapping entities in their study. Recently, Chandran et al. also suggested that ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus are distinct entities and that a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus should be considered in patients with past or current evidence of lichen planus.[8] Though a potential clue, majority (70-85%) of patients present with only macular pigmentation without lichen planus elsewhere.[3],[9]

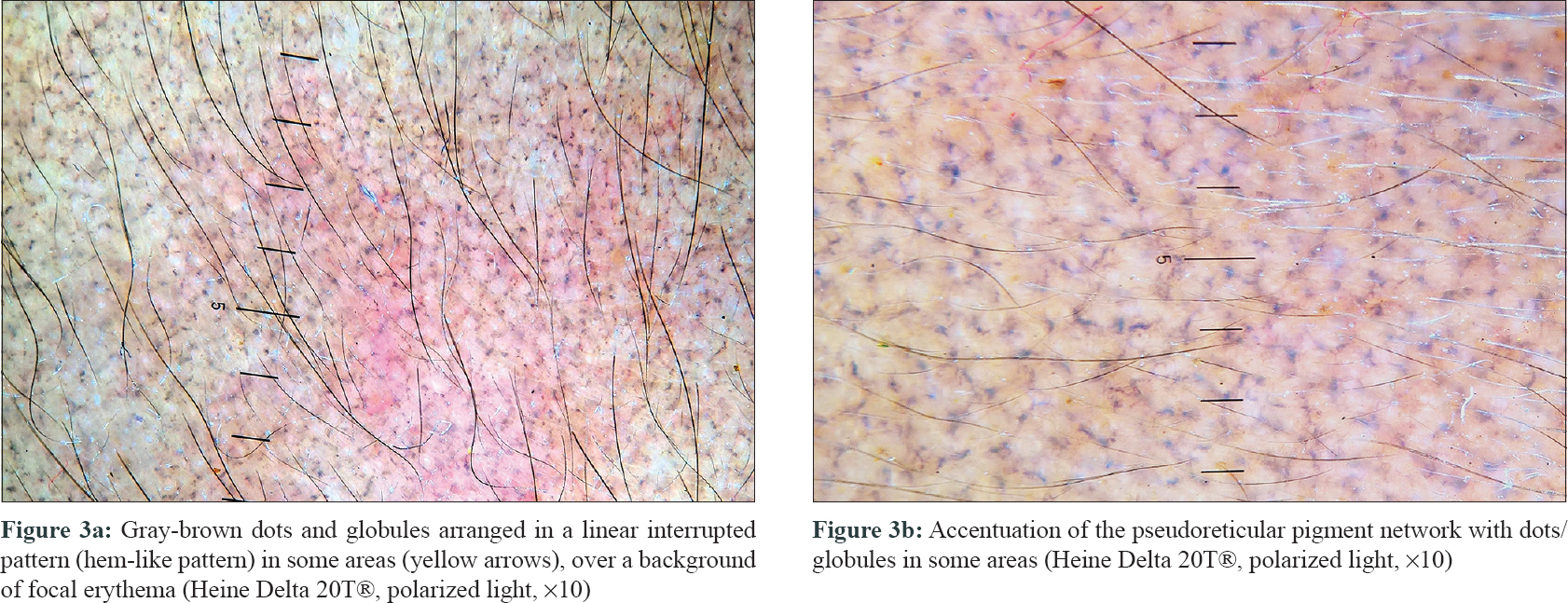

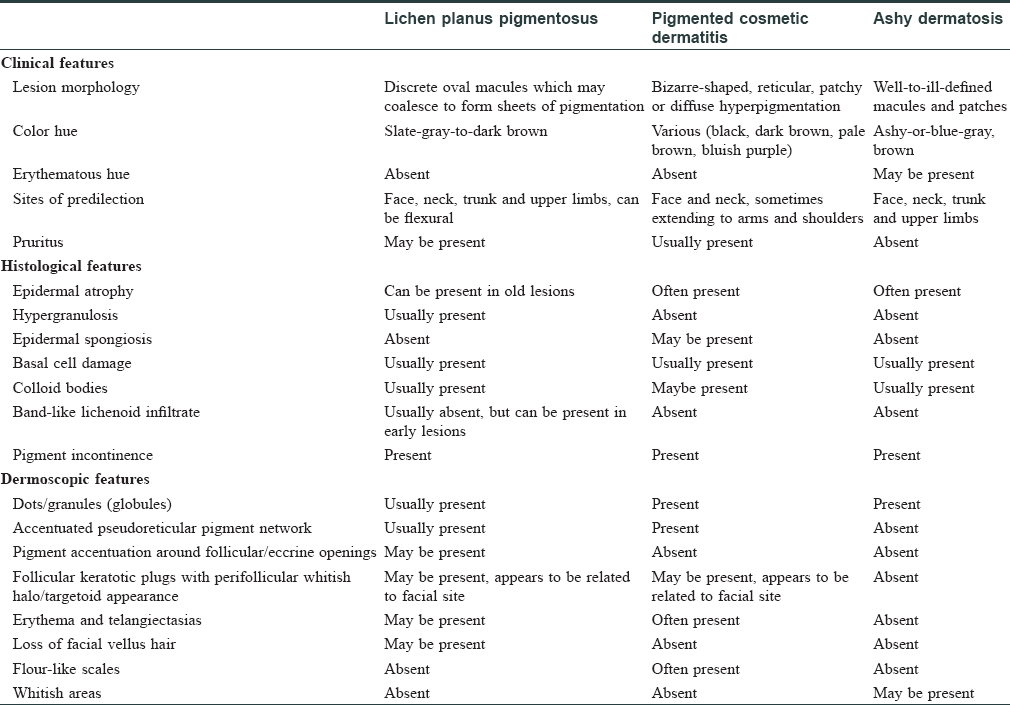

One faces similar dilemma when trying to discern lichen planus pigmentosus from pigmented cosmetic dermatitis as well. Nakayama believed that the macules in pigmented cosmetic dermatitis are darker than lichen planus pigmentosus, and are usually bizarre-shaped, patchy or reticulate. Histological differences include epidermal spongiosis and lack of a band-like lichenoid infiltrate.[10] These clinical patterns of pigmentation have been reported in lichen planus pigmentosus as well, whereas a lichenoid infiltrate is seen only in a subset of cases (18–63%), probably in early active lesions.[9],[11] The clinical and histological differences are debatable, and even patch testing does not appear to be a reliable tool. While not every patient diagnosed as pigmented cosmetic dermatitis has a positive patch test, contact sensitivity to para-phenylenediamine, nickel, fragrances and other cosmetics has been reported in lichen planus pigmentosus and ashy dermatosis also.[12] We found one third (n = 17/50, 34%) of our patients with facial lesions of lichen planus pigmentosus to have a positive patch test. Dermoscopic examination revealed gray-brown dots/globules as the most common finding [Figure - 3]a, followed by accentuation of pseudoreticular network [Figure - 3]b. Further, we did not find any significant differences in the dermoscopic findings between patients with and without positive patch test results.[13] Similar dermoscopic findings have been reported by Pirmez et al. in lichen planus pigmentosus.[14] Some of these, such as pseudonetwork and dots/globules, have been reported in Riehl's melanosis as well.[15] Dermoscopy of ashy dermatosis, reported in only a few cases so far, is also similar.[16] Dermoscopic evaluation of these disorders is still at a nascent stage, and its utility in their differential diagnosis needs to be further explored. The clinical, histological and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus, pigmented cosmetic dermatitis and ashy dermatosis, as described in the literature, are summarized in [Table - 1].

|

| Figure 3: |

The differentiating points among these entities are too variable (such as pruritus, pigment hue, pattern, symmetry) and too subtle (erythematous halo) to be regarded as robust discriminating criteria. The occurrence of classic lichen planus in patients with ashy dermatosis further suggests that the two disorders may be related.[17] It is likely that these “differences” are merely variations in the spectrum of the same disease or may represent different stages in the evolution of disease. A disease may have different names in different regions – what we prefer to call “lichen planus pigmentosus” in the Indian subcontinent may be more commonly known as “ashy dermatosis” in Latin America. We believe that these pigmented macules represent a clinical reaction pattern, instead of a specific disease, with different underlying causes. Triggers can be several – contact allergens, food allergens, drugs, viral infections or a systemic cause such as thyroid dysfunction. A subset of these cases may truly be idiopathic. Irrespective of what we choose to label it, a thorough history regarding drugs, cosmetics and other potential allergens is essential, which will dictate further management. In the absence of unambiguous clinicopathological differences, should a distinction be made among these overlapping entities?. Is there a difference in the natural course of these entities and/or response to treatment or removal of implicated allergens? Currently available information on these aspects is limited but there appears to be no significant difference.[7],[11] Future prospective carefully designed studies are needed to answer these important questions. Lack of a uniform nomenclature has been a hindrance in furthering research on these poorly understood entities. A global forum is presently working to reach a consensus on the nomenclature. Till that time, a descriptive term such as “macular hyper-pigmentation of uncertain etiology” may be better which encompasses the clinical and histological features of these pigmentary disorders, while also emphasizing their poorly understood etiopathogenesis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Ramirez CO. Los Cenicientos: Problema Clinico. In: Report of the First Central American Congress of Dermatology, San Salvador, 5–8 December, 1957. San Salvador: Central American Dermatological Society, 1957;122-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F. Erythema dyschromicum perstans a hitherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol 1961;36:457-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, Nayak NC. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica 1974;149:43-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Nakayama H, Harada R, Toda M. Pigmented cosmetic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol 1976;15:673-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Bhutani LK. Ashy dermatosis or lichen planus pigmentosus: what is in a name? Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:133.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Bhutani LK. Pigmented contact dermatitis vs lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol. 1977;16:860-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, Hojyo T, Dominguez-Soto L. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol 1992;31:90-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Chandran V, Kumarasinghe SP. Macular pigmentation of uncertain aetiology revisited: two case reports and a proposed algorithm for clinical classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;45-49.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, Parsad D, Radotra BD. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28:481-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Nakayama H. Authors' reply: Pigmented contact dermatitis vs. lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol 1977;16:861-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: An open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:535-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Tienthavorn T, Tresukosol P, Sudtikoonaseth P. Patch testing and histopathology in Thai patients with hyperpigmentation due to erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, and pigmented contact dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2014;32:185-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sharma VK, Gupta V, Pahadiya P, Vedi KK, Arava S, Ramam M, et al. Dermoscopy and patch testing in patients with lichen planus pigmentosus on face: A cross-sectional observational study in fifty Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:656-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, Campos-do-Carmo G, Valente NS, Romiti R, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:1387-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Wang L, Xu AE. Four views of Riehl's melanosis: Clinical appearance, dermoscopy, confocal microscopy and histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:1199-206.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Martín JM, López V, Jordá E, Monteagudo C. Ashy dermatosis with significant perivascular and subepidermal fibrosis. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:510-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Berger RS, Hayes TJ, Dixon SL. Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus: Are they related? J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;21:438-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

24,782

PDF downloads

3,562