Translate this page into:

Atopy patch test

2 Department of Dermatology, Calcutta National Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

3 Department of Pediatric Dermatology, Institute of Child Health, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Correspondence Address:

Varsha Vaidyanathan

C1/211, Janakpuri, New Delhi - 110 058

India

| How to cite this article: Vaidyanathan V, Sarda A, De A, Dhar S. Atopy patch test. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019;85:338-341 |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing, intensely pruritic, inflammatory skin condition with a significant socioeconomic importance and a negative impact on quality of life.[1] Usually, there is an early onset but it can start at any age.[2] The worldwide prevalence of childhood atopic eczema varies between 3% and 20.5% while in India it is between 2.4% and 6%.[3]

Although the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis is mainly clinical as per the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka,[4] it is best understood as a chronic inflammatory condition with both IgE and non-IgE-mediated immune dysregulation.[5] The skin shows a poor barrier function, likely due to a filaggrin mutation, allowing the entry of allergens; hypersensitivity to these allergens worsens atopic dermatitis.[6] Conversely, avoidance of these allergens leads to an improvement. Both food and aeroallergens are considered to have a role, and they can be evaluated based on the history of exposure along with laboratory tests.

Two types of hypersensitivity reactions are involved in atopic dermatitis:

- Immediate type I IgE-mediated – diagnosed with skin prick tests and measurement of serum-specific IgE

- Delayed type IV T cell-mediated – The patch test is a standard method to assess delayed hypersensitivity to contact allergens, a modification of which – the atopy patch test – is used in atopic dermatitis.

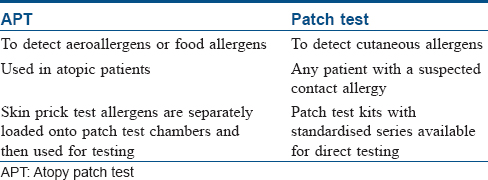

Differences between atopy patch test and patch test are shown in [Table - 1].

Definition

Atopy patch test is an epicutaneously applied patch test procedure with allergens known to evoke IgE-mediated reactions with the test sites evaluated for a delayed hypersensitivity type eczematous reaction after 48–72 hours.[7]

History

The pioneers of the atopy patch test were Rostenberg and Sulzberger who in 1937 used aeroallergens in patch testing.[8] However, it was not until 1982 that the patch test was performed specifically in atopic dermatitis patients by Mitchell.[9] Ring coined the term “atopy patch test” in 1989.[10] At present, the most widely followed protocol is that of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis.[11]

Indications

- Patients in whom an aeroallergen or food allergen is suspected but there is no positive specific IgE or a positive skin prick test

- Severe and/or persistent atopic dermatitis where trigger factors are unknown

- Multiple IgE sensitizations without proven clinical relevance in patients with eczema.

Contraindications

- Acute flares of eczema, especially on the area to be tested

- Pregnancy and lactation

- Immunodeficiencies

- Ongoing immunosuppressive therapies

- Autoimmune diseases.

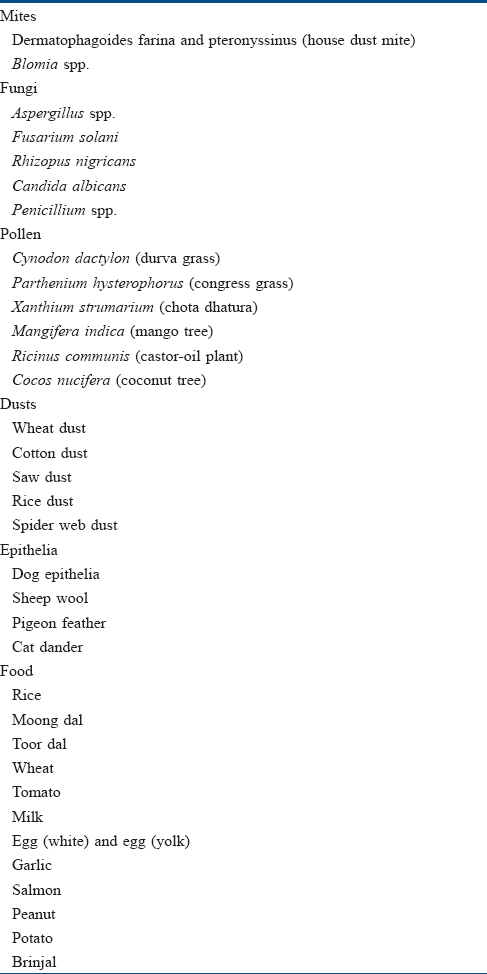

Materials

Internationally, a few commercial kits are available – ALK-Abello, Diallertest and Stallergenes. Different allergens used include prick test solutions on filter paper, purified allergens in hydrogel or in petrolatum and native food. In India, patch test solutions are aqueous allergens (supplied by Creative Drug Industries, Navi Mumbai) which are loaded in aluminum patch test chambers with filter paper using the dropper provided by the manufacturer (Systopic Laboratories, New Delhi).[12] Some of the antigens used in India are listed in [Table - 2]. Others include corn, potato, peanut, soy, chicken, beef, pork, fish, cockroach antigens and tree pollen.[13] Isotonic saline solution or petrolatum can be used as the negative control. Best results are obtained with purified allergens with a known protein content. Allergen strengths are expressed in protein nitrogen units for aeroallergens and 1% weight by volume for food allergens. Protein nitrogen unit between 5 and 7 is ideal. Allergen concentration needs to be higher for atopy patch test than skin prick test.[7]

Technique

Certain precautions need to be taken before performing atopy patch test:[14]

- Area should be nonlesional

- Avoid topical steroids for 5 days

- No ultraviolet radiation for 4 weeks

- Avoid oral antihistamines for at least a week

- Oral steroids and immunosuppressants are stopped depending on the dose and duration (generally 4 weeks)

- No pretreatment of the area, e.g. tape stripping or acetone painting.

Using a dropper, the allergen extracts are placed on a filter paper loaded individually into 12-mm aluminum test cups. These are then placed on the skin of the back using an adhesive tape. Patient is asked to avoid activities such as vigorous exercise and sweating that may lead to the dislodgement of cups. The test chambers are removed after 48 hours when the first reading is done. Final reading is at 72 hours.[15],[16]

Reading

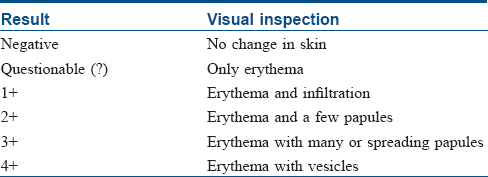

Readings are based on the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis key shown in [Table - 3]. This is roughly similar to the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group reading key used for conventional patch testing.[11]

Discussion

Important aeroallergens that cause atopic flares are house dust mites, tree and grass pollen and animal dander. House dust mites were found to be the most common cause for atopy patch test positivity followed by grass pollen, birch pollen and cat dander in various studies from Germany,[17] the Czech Republic,[12] Croatia[18] and Thailand.[19] Interestingly, in India, parthenium accounted for nearly half of the atopy patch test positivity (42%), followed by house dust mites and Cynodon.[13] In one study, more urban patients than rural patients showed positive atopy patch test, and, of them, the most frequent allergen in the urban group was house dust mites and grass pollen for the rural group, possibly indicating the role of extent of exposure to the allergens.[12] A significant association was found between positive atopy patch test results for aeroallergens and an air-exposed eczema pattern in a Chinese study.[14] Strong atopy patch test positivity to house dust mites is associated with extensive atopic dermatitis suggesting that sensitization to house dust mite allergens plays a significant role in determining the severity of atopic dermatitis.

Important food allergens, known to cause not only atopic flares but also gastrointestinal disturbances, include cow's milk, egg, wheat proteins, soy, peanuts, seafood and rice. Food allergy depends upon the child's age and the eating traditions of the family and the nation. Milk, soy and egg were the most common allergens causing positive atopy patch test.[19],[20]

The importance here lies in the fact that patients showing positive atopy patch test to food allergens have relief from atopic flares and gastrointestinal complaints on eliminating the offending food from the diet.[21],[22] Food allergens were found to be less significant compared to the aeroallergens in an Indian study.[13] Atopy patch test has also been performed with food additives, implicating carmine in the evolution of atopic dermatitis in some patients.[23]

Significance of Atopy Patch Test

Atopy patch test helps to determine the patients in whom atopic flares are related to extrinsic allergen exposure, and these patients can be counselled to avoid these triggers as far as possible. Although it is not possible to completely eliminate house dust mites, a few changes can help minimize the exposure such as:

- Removal of wall-to-wall carpets from the house

- Avoid keeping pets in the house

- Use of dust mite-proof mattress protectors and pillowcases

- Frequently washing bed sheets in hot water

- Installing high-efficiency media filter in airconditioning unit.

Narrowing down the allergens to a select few, especially in the case of food allergens, can avoid unnecessary elimination of large food groups from the diet.

While double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge is still the gold standard for diagnosing food allergy, the procedure involves repeated food administration over a period of few hours and carries the risk of dangerous anaphylaxis in a few patients.[24] Atopy patch tests can be used as a substitute here. In one study, atopy patch test predicted the results of oral food challenge in 28 out of 33 cases. There was 100% negative predictive value for atopy patch test.[25] Another study showed that positive predictive value was best for skin prick test (0.91) followed by radioallergosorbent test (RAST) (0.82) followed by atopy patch test (0.63).[26] Atopy patch test can be a useful tool to study the pathomechanisms of atopic dermatitis.

The test can be performed at a younger age. Atopy patch test has been found to be positive earlier than skin prick test in small children with food allergies, especially in case of cereals.[27] Specificity of atopy patch test ranges from 69–92% and sensitivity 42–75%.[7] Specificity and sensitivity of atopy patch test vary for different allergens ranging from a specificity of 43.5% for milk to 90% for barley and sensitivity of 90.2% for milk to 98.7% for barley.[28]

However, atopy patch test is not suitable for diagnosing immediate food allergies. It is expensive, time-consuming and cumbersome. It may be difficult to interpret in cases of “angry back syndrome” where a strong positive patch test could cause hyperreactivity to other patch tests. Being prone to skin irritations, atopic patients may show higher degree of false positive reactions. Different results may be obtained with variations in allergen (whole mite vs mite extract), allergen concentration, vehicle, site of testing, skin condition at the time of testing and reading time. There can be local flares of eczema, irritation to the adhesive used and urticarial reactions to allergens such as egg and soy.

Conclusion

Atopy patch test is generally not considered in isolation. It can be thought of as another arrow in the quiver available for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. It should be used in addition to a good history, clinical examination and skin prick test and serum-specific IgE. A combination of all these tools helps in a better understanding of atopic dermatitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016;387:1109-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:925-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Bearley R, Keil V, Mutius EV, Pearce N. World wide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema ISAAC. Lancet 1998;351:1225-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic eczema. Acta Dermatol Venereol 1980;92:44.e47.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Wollenberg A, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis: From the genes to skin lesions. Allergy 2000;55:205-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Thyssen JP, Kezic S. Causes of epidermal filaggrin reduction and their role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:792-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Wollenberg A, Vogel S. Patch testing for noncontact dermatitis: The atopy patch test for food and inhalants. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2013;13:539-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Rostenberg A, Sulzberger MB. Some results of patch tests. Arch Dermatol 1937;35:433-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Mitchell EB, Crow J, Chapman MD, Jouhal SS, Pope FM, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Basophils in allergen-induced patch test sites in atopic dermatitis. Lancet 1982;1:127-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Ring J, Kunz B, Bieber T, Vieluf D, Przybilla B. The “atopy patch test” with aeroallergens in atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989;82:195.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Turjanmaa K, Darsow U, Niggemann B, Rancé F, Vanto T, Werfel T, et al. EAACI/GA2LEN position paper: Present status of the atopy patch test. Allergy 2006;61:1377-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Krupa Shankar DS, Chakravarthi M. Atopic patch testing. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:467-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Nečas M. Atopy patch testing with airborne allergens. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2013;22:39-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Dou X, Kim J, Ni CY, Shao Y, Zhang J. Atopy patch test with house dust mite in Chinese patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:1522-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

de Bruin-Weller MS, Knol EF, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA. Atopy patch testing – A diagnostic tool? Allergy 1999;54:784-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Rancé F. What is the optimal occlusion time for the atopy patch test in the diagnosis of food allergies in children with atopic dermatitis? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2004;15:93-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Darsow U, Vieluf D, Ring J. Evaluating the relevance of aeroallergen sensitization in atopic eczema with the atopy patch test: A randomized, double-blind multicenter study. Atopy Patch Test Study Group. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:187-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Kuljanac I, Milavec-Puretić V. Atopy patch test with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Dp 1) in atopic dermatitis patients. Coll Antropol 2006;30:181-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Visitsunthorn N, Chatpornvorarux S, Pacharn P, Jirapongsananuruk O. Atopy patch test in children with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016;117:668-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Kutlu A, Karabacak E, Aydin E, Ozturk S, Taskapan O, Aydinoz S, et al. Relationship between skin prick and atopic patch test reactivity to aeroallergens and disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2013;41:369-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Syrigou E, Angelakopoulou A, Zande M, Panagiotou I, Roma E, Pitsios C, et al. Allergy-test-driven elimination diet is useful in children with eosinophilic esophagitis, regardless of the severity of symptoms. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2015;26:323-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Rokaite R, Labanauskas L, Balciūnaite S, Vaideliene L. Significance of dietotherapy on the clinical course of atopic dermatitis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45:95-103.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Catli G, Bostanci I, Ozmen S, Dibek Misirlioglu E, Duman H, Ertan U, et al. Is patch testing with food additives useful in children with atopic eczema? Pediatr Dermatol 2015;32:684-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Jurakić Toncić R, Lipozencić J. Role and significance of atopy patch test. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2010;18:38-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Fogg MI, Brown-Whitehorn TA, Pawlowski NA, Spergel JM. Atopy patch test for the diagnosis of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2006;17:351-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Majamaa H, Moisio P, Holm K, Kautiainen H, Turjanmaa K. Cow's milk allergy: Diagnostic accuracy of skin prick and patch tests and specific IgE. Allergy 1999;54:346-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Strömberg L. Diagnostic accuracy of the atopy patch test and the skin-prick test for the diagnosis of food allergy in young children with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:1044-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Beausoleil JL, Shuker M, Liacouras CA. Predictive values for skin prick test and atopy patch test for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:509-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

14,222

PDF downloads

4,905