Translate this page into:

Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: Old wine in a new bottle

2 Era's Lucknow Medical College, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 AMRI Hospitals, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Correspondence Address:

A K Bajaj

Bajaj Skin Clinic, 3/6, Panna Lal Road, Allahabad, (UP)

India

| How to cite this article: Bajaj A K, Saraswat A, Upadhyay A, Damisetty R, Dhar S. Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: Old wine in a new bottle. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:109-113 |

Abstract

Background: Chronic urticaria (CU) is one of the most challenging and frustrating therapeutic problems faced by a dermatologist. A recent demonstration of abnormal type 1 reactions to intradermal autologous serum injections in some CU patients has led to the characterization of a new subgroup of "autoimmune chronic urticaria". This has rekindled interest in the age-old practice of autologous blood injections as a theoretically sound treatment option in these patients. Aims: To evaluate the efficacy of repeated autologous serum injections (ASIs) in patients with recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Methods: A cohort of 62 (32 females) CU patients with a positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) (group 1) was prospectively analyzed for the efficacy of nine consecutive weekly autologous serum injections with a postintervention follow-up of 12 weeks. Another group of 13 (seven females) CU patients with negative ASST (group 2) was also treated similarly. In both groups, six separate parameters of disease severity and activity were recorded. Results: Demographic and disease variables were comparable in both groups. The mean duration of disease was 1.9 � 0.3 years (range = 3 months to 32 years) in group 1 and 1.5 � 0.2 years (range = 3 months to 10 years) in group 2. In the ASST (+) group, 35.5% patients were completely asymptomatic at the end of the follow-up while an additional 24.2% were markedly improved. In the ASST (−) group, these figures were 23 and 23% respectively. The intergroup difference for complete subsidence was statistically significant (P < 0.05). In both groups, the most marked reduction was seen in pruritus and antihistamine use scores followed by the size and frequency of the wheals. Conclusion: Autologous serum therapy is effective in a significant proportion of ASST (+) patients with CU. A smaller but still substantial number of ASST (−) patients also benefited from this treatment.

|

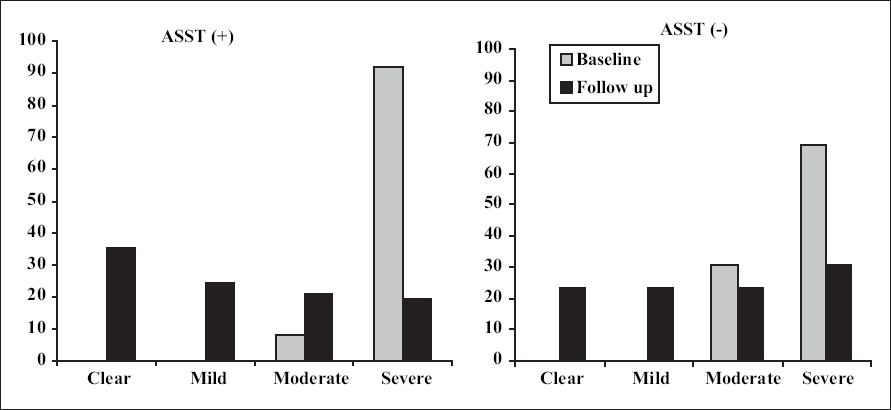

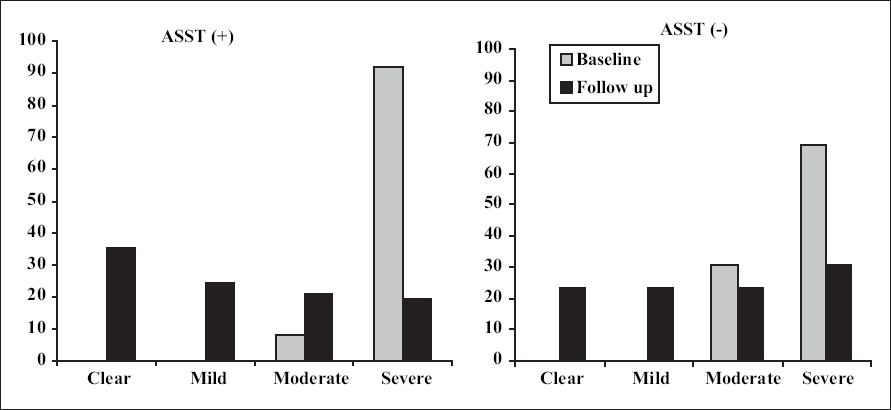

| Figure 2: Proportion of patients with different severity grades at baseline and follow-up in the two groups |

|

| Figure 2: Proportion of patients with different severity grades at baseline and follow-up in the two groups |

|

| Figure 1: Percentage Fall in the total severity score in ASST (+) and ASST (-) patients with time |

|

| Figure 1: Percentage Fall in the total severity score in ASST (+) and ASST (-) patients with time |

Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a common and distressing dermatosis characterized by the appearance of evanescent wheals almost daily, continuously for six or more weeks. It is a clinical diagnosis and requires that physical, drug-induced and infection-related urticaria be ruled out by thorough history-taking and relevant investigations. Until recently, all remaining cases were assigned to the rather inelegant category of chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) since no definite cause of CU was known in those cases.

This issue was partially resolved in 1993 when Hide et al. [1] reported that autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor, F cεR Iα cause histamine release in a subset of patients with CU. Subsequent reports established that 27-61% [2],[3],[4],[5] of CU patients, depending on the method of antibody detection, had these circulating antibodies in their blood. The simplest screening method to identify this group of patients having what was termed chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU), was found to be the autologous serum skin test (ASST). [6] Intradermal injection of autologous serum in these patients elicited an immediate-type wheal and flare response indicating the presence of a circulating histamine-releasing factor. These patients with CAU were reported to have a greater number of wheals with a wider distribution, more severe pruritus and more frequent systemic symptoms. [7]

These reports helped explain why some patients with CU responded well to corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs and poorly to H 1 antagonists. Recently, Staubach et al. [8] reported the efficacy of autologous whole blood therapy (AWB) in CAU giving weekly intramuscular injections of whole blood to patients. This mode of treatment was popular in the treatment of several diseases like atopic dermatitis, CU [9] etc earlier but had largely been abandoned in recent times as being "unscientific".

We have attempted to refine AWB by removing the cellular components of blood for intramuscular injections as histamine-releasing factors are present in the serum. This should make the treatment less painful for the patients and easier to administer for the clinician without reducing its efficacy. We conducted this multicenter, prospective, open label trial of autologous serum therapy (AST) in patients with CU and examined its effects on multiple severity parameters.

Methods

Patients

Consecutive patients of either sex with chronic urticaria were assessed for the inclusion criteria of this study, which were: almost daily appearance of wheals for ≥6 months, age> 18 years and willingness for weekly follow-up and injections. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, predominantly physical urticaria, systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive drug use in the past 6 weeks and other systemic illnesses requiring treatment. Demographic variables were recorded and detailed history of disease including history of atopic disorders was taken. A total of 394 patients with CU were screened and ASST was done in all. Out of these, 195 (49.5%) were ASST (+) and the rest were ASST (−). After screening for inclusion and exclusion criteria, 96 ASST (+) patients were recruited for the study. However, only 62 (64.6%) (32 women, 30 men) completed all nine weekly intramuscular injections of autologous serum and returned for at least one posttreatment follow-up 12-16 weeks after the 9 th autologous serum injection. Twenty-eight ASST (−) patients were also recruited for the study, 13 (46.4%) (seven women, six men) completed the protocol requirement as mentioned above.

Autologous serum skin test

Serum was separated by centrifuging patients′ blood at 2000 rpm for 10 min and 0.1 ml of autologous serum, normal saline and histamine (10 µg/ml) were injected intradermally at least 5 cm apart on the volar aspect of the forearm. A 31-gauge needle was used avoiding sites of whealing in the past 24 h and results were read at 30 min. ASST was considered positive when the average of two perpendicular diameters of the autologous serum wheal was ≥1.5 mm more than the normal saline wheal. Long-acting antihistamines were withdrawn at least 3 weeks before and short-acting ones 48 h before testing.

Intervention

All baseline disease parameters were recorded after a week′s run-in period in which patients were allowed to take a short-acting antihistamine orally (pheniramine 25 mg) only when wheals appeared. Thereafter, every week for nine consecutive weeks, 5 ml blood was drawn, serum separated and a 2-ml deep intramuscular injection given in alternate buttocks or upper arms. Rescue antihistamine was permitted as in the run-in period; no other drugs were permitted.

Disease assessment

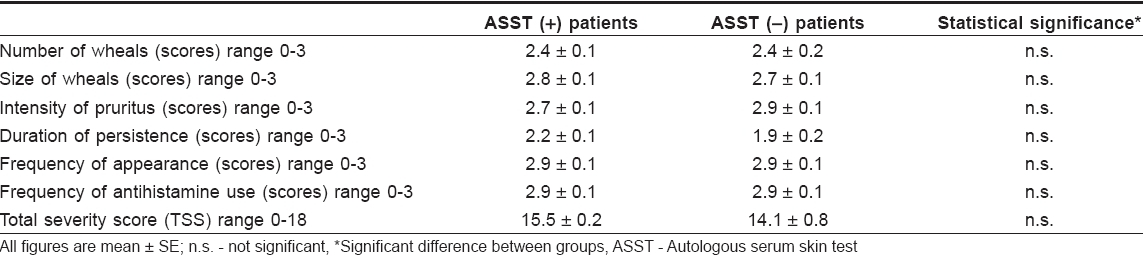

Six separate parameters of disease activity and severity were recorded on a 0-3 scale [Table - 1] at baseline (0 week), end of treatment (9 weeks) and follow-up (21-25 weeks). Based on these, a 0-18 total severity score (TSS) was generated and overall disease severity classified as clear (TSS = 0), mild (TSS 1-6), moderate (TSS 7-12) or severe (TSS 13-18). To account for the powerful placebo effect of weekly injections, we attached less importance to the response immediately after the 9-week treatment period. A period (12-16 weeks) longer than the treatment duration was allowed to elapse before the follow-up assessment was done to ascertain actual long-lasting improvement/remission. The main outcome measure was the fall in total severity scores at the 21-25 week follow-up visit. The secondary outcome measure was the level of rescue antihistamine use at this visit compared to the baseline. A follow-up score of 0 at 21-25 weeks was considered complete remission, a score of 1-6 marked improvement, 6-12 moderate improvement and 13-18 poor/no improvement.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was done on the per-protocol population, i.e., patients completing all nine autologous serum injections and coming for at least one follow-up visit 12-16 weeks after the last injection. For missing values, the last observation-carried-forward method was employed. Nonparametric data was compared by the χ2 test and parametric comparisons were done by two-tailed ′ t ′ test and two-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was fixed as the limit for significance of differences.

Results

The median age of ASST (+) patients was 25 years (range 18-64 years); in the ASST (−) group, the median age was 24 years (range 17-55 years). The duration of urticaria ranged from 6 months to 32 years (median 2.5 years) in ASST (+) patients and 6 months to 10 years (median: 3 years) in ASST (−) patients. A positive personal history of atopy in the form of allergic rhinitis, wheezing or allergic conjunctivitis was present in 29 (46.7%) ASST (+) and five (38.5%) ASST (−) patients (χ2 = 0.58, P = 0.2).

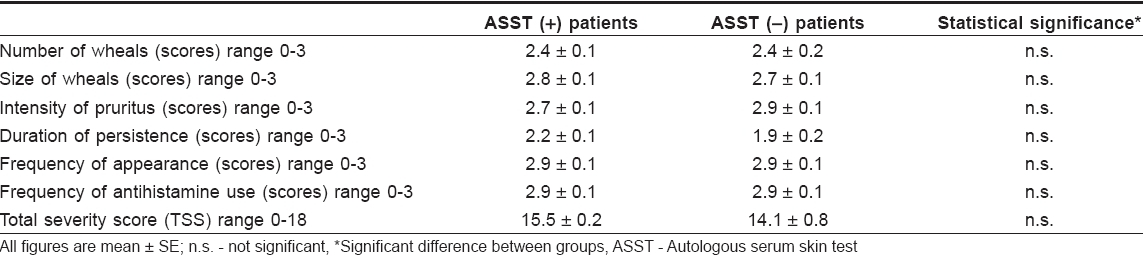

Baseline disease attributes of patients in the two groups are presented in [Table - 2]. A significantly higher proportion of ASST (+) patients were classified as severe compared to the ASST (−) group at baseline (91.9 vs . 69.2%; P = 0.02).

ASST (+) patients had similar mean baseline TSS when compared to ASST (−) patients. However, while TSS at the 9 th week was significantly lower in the ASST (+) group, it was not significantly different at the 21-25 week follow-up.

Patients in both groups showed a downward trend in TSS from baseline to the end of treatment and this fall was statistically significant in both ASST (+) group (mean 15.5 ± 0.2 vs . 7.1 ± 0.6; P = 0.003) and ASST (−) group (mean 14.1 ± 0.2 vs. 10.9 ± 0.5; P = 0.008). This trend continued after the cessation of weekly autologous serum injections with both groups showing statistically significant falls in mean TSS from week 9 until final follow-up. Antihistamine use declined from 100% at baseline in both groups to 38.7% of ASST (+) patients and 23.1% of ASST (−) patients ( P < 0.05) at the end of the study.

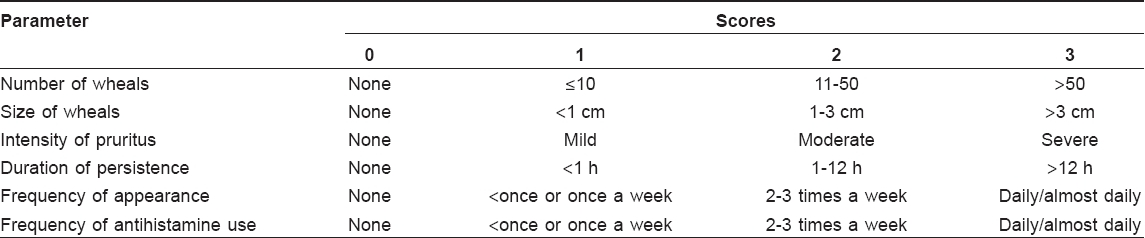

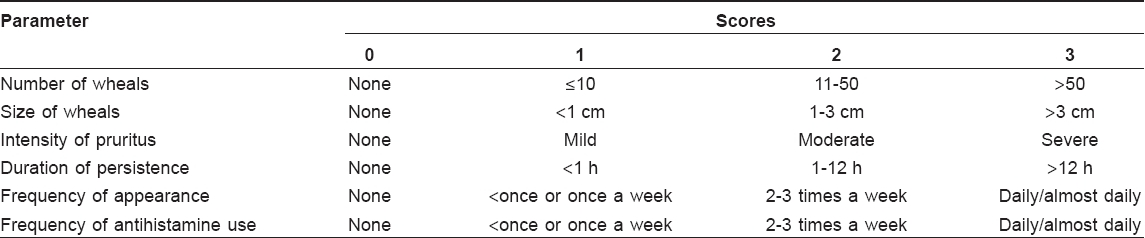

To nullify the effect of varying TSS at baseline, percentage reductions in TSS were calculated for all patients in both groups [Figure - 1]. Mean percentage reduction in the TSS was statistically significant at nine weeks and continued even after the injections were stopped in both groups. The fall was 54% at the 9 th week in ASST (+) patients versus a fall of only 24% in ASST (−) patients ( P = 0.03). Over the next 12-16 weeks, it continued to show a further downward trend in both groups and the final reduction was 65% in ASST (+) and 53% in ASST (−) patients ( P > 0.05). At 9 weeks, a decline from the baseline achieved statistical significance in all parameters in the ASST (+) group and in all except the wheal number ( P = 0.13) and duration of persistence ( P = 0.16) in ASST (−) group. In the initial visit, there were no patients in the clear or mild severity grades in either group [Figure - 2]. However, at the final follow-up visit, 35.5% patients were completely clear and 24.2% had only mild disease in the ASST (+) group. These figures were 23 and 23% respectively in the ASST (−) group.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of autologous serum therapy (AST) in chronic urticaria of more than 6-month duration. We chose to use autologous serum in place of whole blood for the following reasons:

- The circulating autoreactive factor is present in the serum, not in the cellular components of blood.

- Finer needles can be used for injecting serum compared to those with whole blood, reducing patient discomfort and increasing compliance.

- Whole blood must be injected as quickly as possible after being drawn to avoid the possibility of clotting, requiring increased patient co-operation.

Contrary to a previous report, [8] our experience has shown that AST was an effective treatment even in some ASST (−) patients. Similar to most previous reports in CU patients, [3],[4] almost half of the patients in this study (195 of 394, 49.5%) had a positive reaction to autologous serum. However, our figure was lower than that reported by Godse [2] from Mumbai. Demographic and historical parameters were similar in both groups. Although none of the the intergroup differences in the scores of all six severity parameters (lesion size, number, frequency, persistence, itch and antihistamine use) were statistically significant, there was a clear distinction when patients were stratified into mild, moderate and severe categories based on the total severity score (TSS). A significantly larger number of patients in the ASST (+) group were graded as "severe" than the ASST (−) group ( P = 0.02). In 1999, Sabroe et al. [6] reported that ASST (+) patients had more widespread lesions and significantly more severe pruritus and systemic symptoms. However, other reports have revealed no [10] or only subtle differences in the symptomatology of ASST (+) and ASST (−) patients - slightly longer disease duration and higher antihistamine use. [8]

AST was well-tolerated and none of the patients reported any side effects except local soreness lasting from 12 to 24 h. We did not notice any bruising at injection sites although it was reported in some patients given autologous whole blood injections for CU in a prior study. [8]

Staubach et al. [8] performed follow-up evaluation 4 weeks after the last (8 th ) injection using autologous whole blood in their study. We specifically chose a 3-4 times longer follow-up duration than Staubach and co-workers did to accurately assess the longevity of the suppressive effect of this form of treatment.

Our results indicate that almost 60% of ASST (+) patients show a significant improvement in their signs and symptoms after nine weekly ASIs are given [Figure - 1]. This is slightly lower than the figure of 70% reported by Staubach et al. [8] However, the two studies are not easily comparable since they used a somewhat different scoring system and the average disease severity and duration in their patients were significantly lower than in this study.

More importantly, we have shown that improvement is sustained for at least 3-4 months after the last injection. The most gratifying response has been seen in 35% of ASST (+) and surprisingly, 23% of ASST (−) patients who have cleared completely and have not relapsed for 12-16 weeks after the last ASI. In fact, six patients who had complete clearance with ASI have continued to follow up for more than 2 years and have remained asymptomatic. After 12 and 18 months, two of them have relapsed and have been given booster ASIs to which they have responded again (data not shown).

Mean percentage reductions in TSS data [Figure - 2] clearly show that there was a faster and more dramatic decline in severity in the ASST (+) group during the treatment phase. This trend continued for the next 12-18 weeks and ASST (+) scores were still lower than the ASST (−) scores at the final 21-25 week follow-up. However, the difference was statistically not significant at this point (65 vs . 43%, P > 0.05). In comparison, Staubach et al . [8] reported significant reduction only in ASST (+) patients (41%) while ASST (−) patients showed only a 21% fall in severity scores, which was not different from the placebo group.

Since we do not know exactly how AST works, we can only surmise as to the mechanisms behind the significant improvement in almost half of all ASST (−) patients in our study. The first factor is the relatively crude nature of ASST. Bradykinin is released when serum is separated and the complement factor C 5 gets activated to C 5a . Both can cause false positive immediate type reactions. Moreover, there is a poor concordance of ASST positivity with circulating antibodies to IgE or F cεR Iα. Reported rates of ASST (+) patients actually having antiF cεR Iα antibodies vary from 40 [11] to < 20%. [8] This means that most of the patients who react to ASST do not have circulating antiF cεR Iα/IgE antibodies. On the other hand, while initial studies reported < 2% antiF cεR Iα positivity in ASST (−) patients, [11] recent studies have detected these antibodies in as many ASST (−) patients as ASST (+) ones [8] and even in healthy controls. [12] Matters are further complicated by the different methods employed to detect antiF cεR Iα antibodies with immunoblotting being less sensitive than histamine release assays.

Obviously, it is far from clear which circulating factor is identified by a positive ASST. It is quite likely that ASST positivity reflects an autoreactive state to several different circulating factors in the patients′ own blood. False negative results in ASST may partly explain the good response to ASI seen in ASST (−) CU patients in this study.

A significant drawback of this study was its uncontrolled and unblinded nature. We did not choose to use a placebo arm in this study since we chose severely affected patients. A larger placebo-controlled study with unselected CIU patients is warranted to assess the utility of this therapy in our patients.

To conclude, we have demonstrated that the old wine of autohemotherapy is still potent when served in a new bottle as autologous serum injection therapy, and still retains its attraction for physicians and patients alike. We however, do not know exactly how or when it works but it may prove to be a cheap, effective and potentially curative modality in some patients with recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Autologous serum skin test reactivity may not reliably reflect the chances of response to this form of therapy and many ASST-negative patients may also be benefited by this treatment.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded in part by Aventis Pharmaceuticals Limited.

| 1. |

Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, Hakimi J, Kochan JP, Greaves MW. Autoantibodies against the high affinity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1599-604.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Godse KV. Autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:283-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Fiebiger E, Maurer D, Holub H, Reininger B, Hartmann G, Woisetschlδger M, et al. Serum IgG autoantibodies directed against the alpha chain of Fc epsilon RI: A selective marker and pathogenetic factor for a distinct subset of chronic urticaria patients? J Clin Invest 1995:96:2606-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ferrer M, Kinet JP, Kaplan AP. Comparative studies of functional and binding assays for IgG anti Fc epsilon Riα (α-subunit) in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:672-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Piconi S, Trabattoni D, Iemoli E, Fusi ML, Villa ML, Milazzo F, et al. Immune profiles of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2002;128:59-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: A screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:446-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Sabroe RA, Seed PT, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Comparison of the clinical features of patients with and without anti- Fc epsilon RI or ani IgE antibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:443-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Staubach P, Onnen K, Vonend A, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Tschentscher I, et al. Autologous whole blood injections to patients with chronic urticaria and a positive autologous serum skin test: A placebo-controlled trial. Dermatology 2006;212:150-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Bocci V. Autohaemotherapy after treatment of blood with ozone: A reappraisal. J Int Med Res 1994;22:131-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Nettis E, Dambra P, D'Oronzio L, Cavallo E, Loria MP, Fanelli M, et al. Reactivity to autologous serum skin test and clinical features in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol 2002;27:29-31.

et al. Reactivity to autologous serum skin test and clinical features in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol 2002;27:29-31.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Niimi N, Francis DM, Kermani F, O'Donnell BF, Hide M, Kobza-Black A, et al. Dermal mast cell activation by autoantibodies against the high affinity IgE receptor in chronic urticaria. J Invest Dermatol 1996;106:1001-6.

et al. Dermal mast cell activation by autoantibodies against the high affinity IgE receptor in chronic urticaria. J Invest Dermatol 1996;106:1001-6.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Horn MP, Gerster T, Ochensberger B, Derer T, Kricek F, Jouvin MH, et al. Human anti-Fc- epsilon RI alpha autoantibodies isolated from healthy donors cross-react with tetanus toxoid. Eur J Immunol 1999;29:1139-48.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

9,454

PDF downloads

1,575