Translate this page into:

Clinical analysis of 20 cases of cutaneous extranodal NK/T-Cell lymphoma

Corresponding author: Dr. Guan Jiang, Department of Dermatology, Xuzhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital, Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China, dr.guanjiang@xzhmu.edu.cn

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Wang D, Min S, Lin X, Jiang G. Clinical analysis of 20 cases of cutaneous extranodal NK/T-Cell lymphoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:718-24

Abstract

Background

To investigate the clinical features, pathological features and prognostic factors of cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (CENKTL).

Methods

A total of 20 cases with CENKTL from February 2013 to November 2021 were analysed retrospectively.

Results

The patients included 15 men and five women, and their ages ranged from 19 to 92 (median age of 61) years. The most common lesions were on the extremities, followed by the trunk. Histopathological examination showed atypical lymphocyte infiltrate in dermis and subcutaneous fat. The tumour tissue showed vascular proliferation, vascular occlusion, and coagulation necrosis. In situ hybridisation revealed that 20 patients were positive for Epstein–Barr virus-coding ribonucleic acid. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumour cells were positive for CD3 (18/20 and 90%), CD56 (19/20 and 95%), T-cell intracellular antigen (TIA-1) (13/14 and 92.9%) and CD20 (5/20, 25%). About 20 patients were positive for Ki-67 with values of 30–90%. A total of 11 of the 20 patients died, and two patients were lost to follow-up. The 2-year overall survival was 24%, and the median overall survival was 17 months. Univariate analysis revealed that involvement of lymph nodes (P = 0.042) correlated with worse survival.

Limitation

This is a retrospective study design and has a limited number of patients.

Conclusion

CENKTL is rare and has a poor prognosis. Diagnosis is challenging due to non-specific clinical symptoms and histopathology results. A comprehensive judgement should be made based on related clinical manifestations and histopathological and molecular examination. Lymph node involvement is an independent prognostic factor for CENKTL.

Keywords

Cutaneous lesion

extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

histopathology

immunohistochemistry

prognosis

Plain language summary

Cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (CENKTL) has various histopathological findings and diverse clinical manifestations. We performed a retrospective study of CENKTL to investigate the clinical, pathological features and prognostic factors. A total of 20 cases with CENKTL (15 males and 5 females) were analysed. Histopathological examination showed atypical lymphocyte infiltrate in dermis and subcutaneous fat. The tumour tissue showed vascular proliferation, vascular occlusion, and coagulation necrosis. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated expression of CD2, CD3ε, cytotoxic protein (TIA-1, perforin and granzyme B) and CD56. These findings, in conjunction with Epstein–Barr virus-coding ribonucleic acid in situ hybridisation positivity, confirmed a diagnosis of CENKTL. Eleven of the 20 patients died, and two patients were lost to follow-up. The 2-year overall survival was 24%, and the median overall survival was 17 months. Univariate analysis revealed that lymph node involvement correlated with worse survival.To conclude, a comprehensive judgement should be made based on clinical manifestations and histopathological and molecular examination. Additionally, lymph node involvement is an independent poor prognostic factor for CENKTL.

Introduction

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) is a rare and highly malignant type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which could have features such as vascular destruction and marked tissue necrosis. It is closely related to infection with the Epstein–Barr virus. 1 Primary ENKTL exhibits a predilection to develop in the upper aerodigestive tract and most commonly occurs in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and oral cavity. The skin is the most common initial extra nasal presentation, but involvement of skin is extremely rare. According to the primary site of involvement, cutaneous ENKTL can be divided into two subgroups: primary CENKTL (PCENKTL), which has no evidence of systemic or extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis, ENKTCL with secondary cutaneous involvement (SCENKTL), and ENKTCL with extra nasal manifestation and secondary cutaneous involvement. 2 Although ENKTL has been widely evaluated, there is only limited data about the clinicopathological characteristics or prognosis of patients with CENKTL. Therefore, in this study, we reviewed 20 cases of CENKTL to improve our histopathological and clinical understanding of this rare disease.

Materials and methods

The data of 20 cases of CENKTL in the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University and Xuzhou Central Hospital from February 2013 to November 2021 were collected. CENKTL was diagnosed based on the findings of a skin lesion biopsy. The diagnostic criteria were based on the World Health Organization’s (2016) classification of lymphoid neoplasms. 3 This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

The clinical and pathological data collected included the following: clinical manifestations, laboratory examination and histopathology findings, immunophenotype, type of treatment and last follow-up, treatment response, progression, and survival data. Then, relevant literature was reviewed to summarise the clinical features, histopathological characteristics, therapeutic strategies, and prognosis for CENKTL.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package For The Social Sciences 23.0. Survival was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the prognostic factors. Results are presented as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and laboratory data

The clinical characteristics and laboratory examinations of 20 CENKTL patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The age range of the 20 patients (15 men and five women) at diagnosis was 19–92 years. A total of 12 (60%) patients were older than 60 years, and the median patient age was 61 years. Tthe skin lesions of some cases can be seen in Figures 1a and 1b. †B symptoms; 1. Unexplained fever (>38°C) for >3 consecutive days, 2. Night sweats, 3. Weight loss at 6 months > 10% in months. PCENKTL, primary cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma;, SCENKTL, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma with secondary spread to the skin; C, chemotherapy; R, radiotherapy; ASCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; U, Untreated; DOD, died of disease; AWD, alive with disease; AWR, alive with recurrence; ”/”, means unknown ASCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; EBER, Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs; TIA, transient ischaemic attack

Case No.

Sex

Age

Diagnosis

Cutaneous involvement

Cutaneous performance

B symptoms†

Treatment

Outcome (mo)

1

M

61

PCENKTL

Back, chest, limbs

Erythema, ulceration

Fever

C + ASCT

AWR 52

2

M

54

PCENKTL

Left leg

Ulceration

Night sweat

C + mR

DOD 24

3

M

35

SCENKTL

Chest

Nodule

None

C

AWR 22

4

M

64

PCENKTL

Nose

Ulceration, crust

Fever

U

DOD 1

5

M

79

SCENKTL

Back, chest

Erythema, nodules

Weight loss

U

DOD 4

6

F

19

PCENKTL

Left leg

Ulceration

Fever

/

/

7

M

73

PCENKTL

Face

Nodules

None

R

DOD 10

8

M

30

SCENKTL

Right leg

Nodule

Night sweat

C + R

DOD 10

9

M

65

PCENKTL

Arms, legs

Ulceration, crust, mass

Fever

C

DOD 3

10

M

91

PCENKTL

Left leg

Ulceration

None

U

AWD 45

11

M

69

SCENKTL

Arms, legs

Ulceration

None

C

DOD 17

12

F

73

PCENKTL

Back, chest

Erythema, mass

Night sweat

R

AWR 10

13

F

75

PCENKTL

Haunch

Ulceration

None

/

/

14

M

74

PCENKTL

Face

Mass

None

C + R

AWR 15

15

M

61

PCENKTL

Face, trunk, limbs

Erythema, mass

None

C

DOD 1

16

M

49

PCENKTL

Face, neck

Mass

Fever

C

DOD 20

17

M

52

PCENKTL

Chest

Ulceration

Fever

C

DOD 3

18

F

35

PCENKTL

Back

Mass

None

C + ASCT

AWR 12

19

M

61

SCENKTL

Face, trunk, limbs

Nodules, ulceration

None

C

DOD 6

20

F

59

SCENKTL

Legs, back

Erythema, ulceration

Weight loss

U

AWD 1

Characteristics

Total

Percentage

Age, median (range) (years)

61(19–92)

≤60

8/20

40%

>60

12/20

60%

Gender

Male

15/20

75%

Female

5/20

25%

Primary tumour

Skin

14/20

70%

Nasal Cavity

6/20

30%

Cutaneous involvement

Solitary

9/20

45%

Multiple

11/20

55%

Distribution of skin lesions

Head and neck

4/20

20%

Trunk

10/20

50%

Extremities

10/20

50%

Generalised

3/20

15%

Clinical features of skin lesions

Plaque

5/20

25%

Papule or nodules

11/20

55%

Ulceration

11/20

55%

B symptoms

Yes

11/20

55%

No

9/20

45%

Lymph node involvement

Yes

7/20

35%

No

13/20

65%

LDH level

Elevated

11/20

55%

Normal

9/20

45%

Ann Arbor Stage

I, II

4/20

20%

III, IV

16/20

80%

Treatment

Chemotherapy

7/20

35%

Radiotherapy

2/20

10%

Chemotherapy + radiotherapy

3/20

15%

Chemotherapy + ASCT

2/20

10%

Untreated

4/20

20%

Unknown

2/20

10%

Outcome

Survival

7/20

35%

Death

11/20

55%

Unknown

2/20

10%

Immunophenotype

CD3ε

18/20

90%

CD20

5/20

25%

CD56

19/20

95%

Granzyme B

10/12

83.3%

TIA-1

13/14

92.9%

EBER

20/20

100%

Ulcerated noduloplaque on the neck

Grouped papules, plaques and nodulo-plaques on the back

Histopathological features

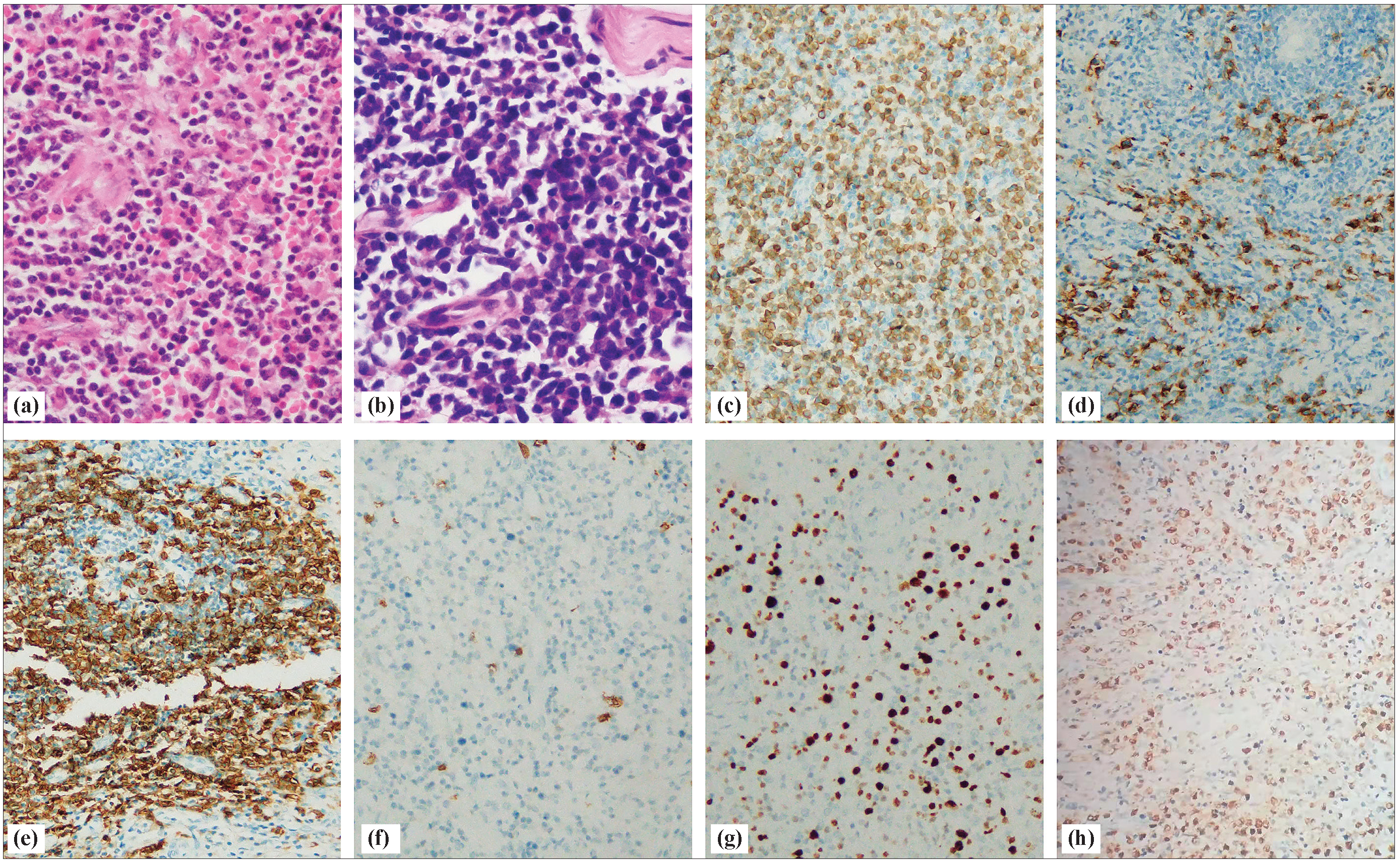

Histopathological examinations showed atypical lymphocyte infiltrate in dermis and subcutaneous fat. Tumour tissue showed vascular proliferation, vascular occlusion, and coagulation necrosis. The tumour cells were mainly medium-sized, and nuclear divisions were common [Figures 2a and 2b].

- Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of patients with cutaneous extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (a–b) Histopathology showing a diffuse infiltrating growth of lymphoid cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×200). (c) CD3ε positive (immunohistochemical staining, ×200). (d) CD56 positive (immunohistochemical staining, ×200). (e) CD20 positive (immunohistochemical staining, ×200). (f) CD20 negative (immunohistochemical staining, ×200). (g) Ki67 positive (immunohistochemical staining, ×200). (h) EBER positive (in situ hybridisation for Epstein–Barr virus-encoded ribonucleic acid, ×200)

Immunohistochemistry and Epstein–Barr virus status

Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumour cells were positive for CD2 (12/13 and 92.3%), CD3ε (18/20 and 90%) [Figure 2c] and CD56 (19/20 and 95%) [Figure 2d], cytotoxic proteins such as TIA-1 (13/14 and 92.9%), perforin (6/9 and 66.7%) and granzyme B (10/12, 83.3%) and CD20 (5/20 and 25%) [Figures 2e and 2f]. The positivity of the proliferating nuclear antigen (Ki-67) (20/20 and 100%) was 30–90% [Figure 2g]. In situ hybridisation showed positive nuclei of Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNA (EBER) (20/20 and 100%) [Figure 2h].

Treatment response and survival analysis

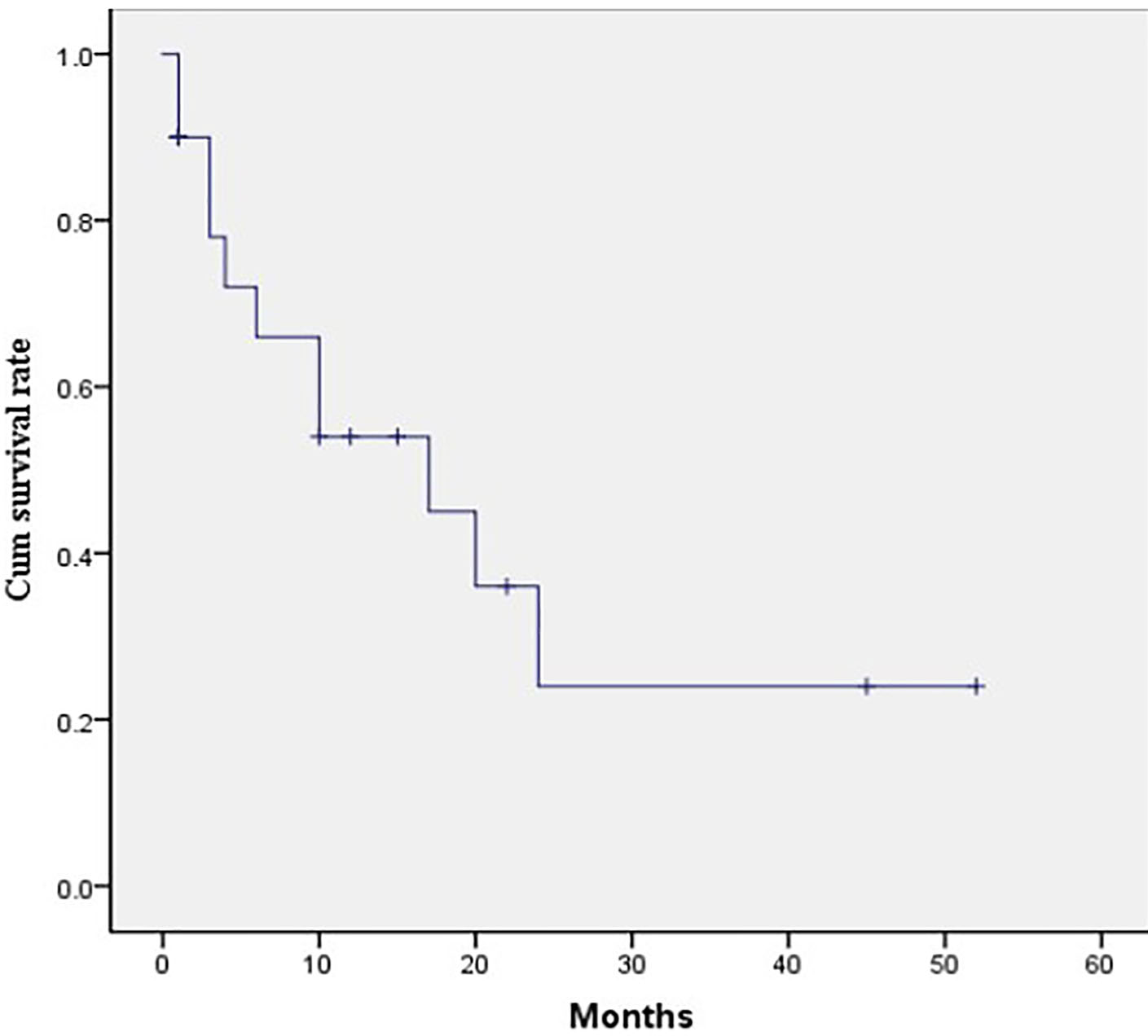

Ten patients died from disease progression, and one patient of cardiovascular disease. Seven patients survived with or without disease, and two patients with PCENKTL were lost to follow-up after 1 month. The median overall survival of nasal ENKTL with secondary spread to the skin was 37.5 months from the first diagnosis and 8 months from the presentation of a cutaneous lesion. Overall survival of patients with localised cutaneous lesions was not significantly different from that of patients with generalised cutaneous lesions, in both PCENKTL (P = 0.681) and secondary lesions (P = 0.156). When all patients were combined into a single cohort, Kaplan-Meier curve analysis revealed that the 2-year overall survival was 24% and the median overall survival was 17 months (95% confidence interval 3.66–30.34 months).

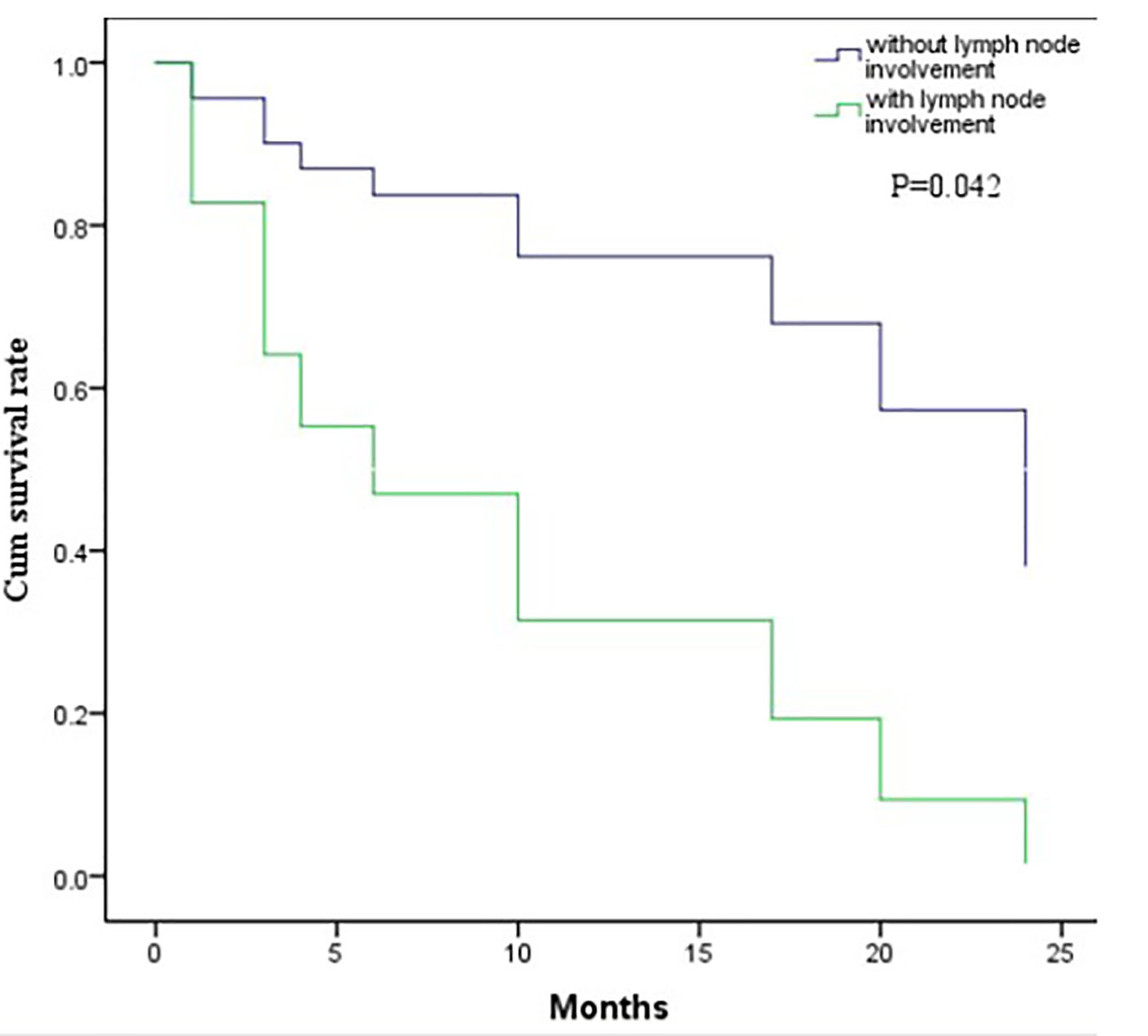

Univariate analysis revealed that lymph node involvement (P = 0.042) correlated with worse survival [Figures 3a and 3b]; however, the presence of B symptoms (P = 0.859), age above 60 years (P = 0.645), high serum Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (P = 0.428), high IPI score (P = 0.473), advanced Ann Arbor stage III-IV) (P = 0.460), CD20-positivity (P = 0.272), primary tumour (P = 0.521) and solitary cutaneous lesions (P = 0.607) were not associated with good prognosis [Table 3].

The 2-year overall survival for patients with cutaneous ENKTL was 24%

Univariate analysis revealed that lymph node involvement was correlated to worse survival

Variable

HR

95% confidence interval

P

Age at diagnosis (> 60 years vs ≤ 60 years)

1.33

0.39–4.61

0.645

Sex (male vs female)

0.04

0–86.75

0.402

Cutaneous involvement (solitary vs multiple)

1.39

0.40–4.78

0.607

Primary tumour (skin vs nasal cavity)

1.52

0.43–5.42

0.521

IPI score (3–5 vs 0–2)

1.58

0.46–5.45

0.473

Serum LDH (elevated vs normal)

0.61

0.17–2.10

0.428

B symptoms (yes vs no)

1.11

0.34–3.68

0.859

Lymph node involvement (yes vs no)

4.25

1.06–17.13

0.042

Ann Arbor stage III–IVvs I–II

2.18

0.28–17.27

0.460

CD20 (positive vs negative)

2.17

0.55–8.63

0.272

Discussion

CENKTL is more frequent in males and frequently occurs in middle-aged adults. In this study, 75% of the patients were men, and the male-to-female patient ratio was 3:1. The median age of the patients was 61 years, and 60% of the patients were older than 60 years, indicating a slightly higher proportion of elderly individuals in comparison with previous studies. The pathogenesis of Epstein–Barr virus tumours is different between elderly and young patients and may be related to the immune degradation caused by ageing. 4

In this study, among all subsets of CENKTL, primary CENKTL was the most common. All forms of nasal ENKTL with cutaneous involvement were present within two years after the initial diagnosis of nasal ENKTL, 5 while the median time in our group was 25.5 months (range 3–76 months). In this study, the clinical features were characterised by erythema, papules, subcutaneous nodules, and ulceration, which was consistent with the previous reports. 6 In all such patients, lesions were more common in the lower extremities, which may be related to T-cell homing. 7 Furthermore, the cutaneous lesions of the lower extremities were more likely to progress to ulceration. The ulceration is probably due to the characteristics of tumour cells destroying blood vessels and the resulting secondary ischemic necrosis in the tissue..

Immunohistochemical findings for this disease often show the neoplastic cells are positive for CD2, CD3ε, cytotoxic protein (TIA-1, perforin and granzyme B) and CD56, frequently negative for other T-lineage markers and B-cell antigen (CD20). CD56 is a marker for NK cells and is positive in 74–76% of cases of ENKTL. 8 In accordance with published literature, there are no significant differences in the clinicopathological features between CD56 positive and CD56 negative cases. 9 In our study, one case was negative for CD56, and the diagnosis of the case was established based on CD3ε, cytotoxic proteins and EBER-positive expression.

Abnormal expression of CD20 in ENKTL is very rare, mainly occurs in extra nasal ENKTL, and is associated with an advanced stage and poor prognosis. The cutaneous lesions of five patients in this group were CD20-positive, they were all in the advanced stage, and four of the five patients died. Interestingly, in three cases of SCENKTL in this study, immunohistochemistry between the primary and relapsed lesions showed only discordant CD20 expression, which may be due to tumour transformation of progenitor cell subsets that co-express CD20 and NK-cell markers, or the neoplastic process after neoplastic transformation, with the latter seeming more plausible. 10 Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism remains to be further studied. In addition, CD20 increases the difficulty of diagnosis, so diagnosis requires a combination of multiple tests, pathology, immunohistochemistry, and EBER in situ hybridisation.

To date, there is no standard chemotherapeutic protocol for ENKTL. The present study found that chemotherapy regimens based on pegaspargase or L-asparaginase yielded promising results. The use of radiotherapy and chemotherapy combined with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has been demonstrated to improve treatment efficacy. 11 , 12 In this group, two patients with skin lesions received ASCT after complete remission of chemotherapy and survived for 41 and 4 months, respectively, without tumour recurrence, showing significant efficacy. However, the number of cases of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for ENKTL is relatively rare, and its clinical efficacy remains to be further studied. In addition, some new therapeutic methods are still being explored to provide new therapeutic directions for it.

Previous studies have shown that the median survival time ranges from 2 to 15 months for patients with CENKTL in most series, and the estimated 5-year survival is 0%. 13 Jiang et al reported that the 3-year overall survival rate of CENKTL was 73.9% for patients who achieved complete response compared with 10.3% for patients who did not. 2 Takata et al found that the 5-year overall survival rate of PCENKTL was 25%. 14 However, the prognosis of patients in this group was poor; more than half of them (61.1%) died, and the 2-year overall survival was only 24%, revealing its high aggressiveness.

PCENKTL had a better prognosis than nasal ENKTL with cutaneous involvement, and patients with single lesions had lower mortality and better prognosis than those with multiple lesions, while the prognosis of PCENKTL with secondary nasal lesions was not significantly different from that of nasal ENKTL. 5 , 15 However, our study was not consistent with other reports, which may be due to the small sample size, and the retrospective nature of the study. Nevertheless, nasal ENKTL with secondary spread to the skin was more likely than PCENKTL to present with generalised skin lesions, 16 consistent with previous studies on ENKTL. The prognostic factors identified by CENKTL included age, stage, distant lymph node involvement, Epstein–Barr virus-deoxyribonucleic virus, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score (ECOG score), serum LDH level, B symptoms, treatment strategy and treatment response. 2 , 17 However, lymph node involvement was the only significant prognostic factor found in our cohort; in univariate analysis. Unfortunately, the role of each type of treatment strategy was not readily assessable because of the limited number of patients and the discrepancy in the treatment received.

Limitations

As a retrospective review of clinical data, this study is subject to a number of limitations, such as the small sample size and incomplete clinical data for some patients. Multi-centre studies with more cases and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm the above-mentioned results in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis are not uncommon because CENKTL is rare with diversified clinical manifestations. For patients in whom clinical symptoms do not match the signs or there is progressive disease progression or long-term treatment is not curative, patients with B symptoms, lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, we should be highly alert to the possibility of this disease. A comprehensive evaluation of clinical manifestations, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and EBER in situ hybridisation results is essential for the diagnosis. The independent inferior prognostic indicator was lymph node involvement in our study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pathogenesis and biomarkers of natural killer T cell lymphoma (NKTL) J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous extranodal natural killer (NK) / T-cell lymphoma: A comprehensive clinical features and outcomes analysis of 71 cases. Leuk Res. 2020;88:106284.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma of nasal type: An age-related lymphoproliferative disease? Hum Pathol. 2017;68:61-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The extent of cutaneous lesions predicts outcome in extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma of the upper aerodigestive tract with secondary cutaneous involvement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:855-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical heterogeneity of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: A national survey of the Korean Cancer Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1477-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymphocyte homing and clinical behavior of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1835-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CD56 extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type presenting as skin ulcers in a white man−. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:390-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnasal lymphoma expressing the natural killer cell marker CD56: A clinicopathologic study of 49 cases of an uncommon aggressive neoplasm. Blood. 1997;89:4501-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type: A prognostic model from a retrospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:612-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open-label, single arm, multicenter phase II study of VIDL induction chemotherapy followed by upfront autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with advanced stage extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56:1205-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autologous stem cell transplantation for nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: A progress report on its value. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1673-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multifocal primary cutaneous extranodal NK/T lymphoma nasal type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:219-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type and CD56-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma: A cellular lineage and clinicopathologic study of 60 patients from Asia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement: ‘Nasal’ vs. ‘nasal-type’ subgroups–a retrospective study of 18 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:333-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: A comparative clinicohistopathologic and survival outcome analysis of 45 cases according to the primary tumor site. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:1002-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological and prognostic study of primary cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: A systematic review. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1499-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]