Translate this page into:

Clinical and serological characteristics of nail psoriasis in Indian patients: A cross-sectional study

2 Department of Microbiology, University College of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Chander Grover

Department of Dermatology and STD, University College of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, University of Delhi, New Delhi - 110 095

India

| How to cite this article: Daulatabad D, Grover C, Kashyap B, Dhawan AK, Singal A, Kaur IR. Clinical and serological characteristics of nail psoriasis in Indian patients: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:650-655 |

Abstract

Background: Nail involvement in psoriasis is common with a lifetime incidence of 80-90%. It may reflect severity of cutaneous involvement and predict joint disease. Yet it remains, poorly studied and evaluated especially in Indian psoriatic patients.Aim: The present study was undertaken to evaluate clinical and serological profile of nail involvement in psoriasis and to assess quality of life impairment associated with nail involvement in Indian patients.

Methods: Consecutive patients with nail psoriasis were assessed for severity of cutaneous disease (psoriasis area severity index score) and nail disease (nail psoriasis severity index score). The impairment in quality of life attributable to nail disease was scored with nail psoriasis quality of life 10 score. All patients were also assessed for joint disease and tested for inflammatory and serological markers as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies.

Results: In our cohort of 38 patients with nail psoriasis, 9 had concomitant psoriatic arthritis. The mean psoriasis area severity index was 14.4 ± 9.6 (range = 0.4–34). The most commonly recorded psoriatic nail changes were pitting (97.4%), onycholysis (94.7%) and subungual hyperkeratosis (89.5%). The mean nail psoriasis severity index score was 83.2 ± 40.1 (range = 5–156) and mean nail psoriasis quality of life 10 was 1.1 ± 0.4. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were raised in 22/38 (57.9%) and 15/38 (39.5%) patients, respectively; rheumatoid factor was positive in 5/38 (13.2%) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody was raised in 4/38 (10.5%) patients.

Limitations: Small sample size and lack of a control group.

Conclusions: In Indian patients with nail psoriasis, severity of nail involvement was found to be poorly correlated with the extent of cutaneous disease. In addition the impact of nail disease on patient's quality of life was found to be minimal. This suggests the need for a quality of life questionnaire suited to the Indian population. Serological markers were raised overall in the study patients and more so in the patients with concomitant arthritis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common and chronic debilitating illness that involves skin, nails and joints. The population prevalence is estimated to be 1%–3% varying across different ethnic groups.[1] Nail involvement in psoriasis is common, affecting roughly 10%–50% patients. With an increase in disease duration, the incidence of nail affliction is found to increase to a lifetime prevalence of 80%–90%.[2] Furthermore, in individuals with joint disease, the nail involvement is higher, to the tune of 90%.[3] However, isolated nail psoriasis is less common with the incidence being between 5%–10%.

Nail involvement in psoriasis is a relatively less explored clinical manifestation. It may precede, develop simultaneously or present after the cutaneous manifestations. Healthy nails carry significant cosmetic as well as functional implications (aiding the fine motor function of the fingers). Nail involvement in psoriasis is therefore found to impair the quality of life.

The present study was undertaken with an aim to document clinical changes in Indian patients with nail psoriasis with special reference to psoriatic arthritis. The quality of life associated with nail involvement and the serological profile was also evaluated.

Methods

In a cross-sectional analysis, 38 consecutive psoriasis patients with nail psoriasis presenting to our tertiary care setup were recruited after an informed written consent. A complete history was taken and physical examination was done. Nail changes were documented along with photographic assessment. The severity of nail involvement was assessed with nail psoriasis severity index [4] and the impact on quality of life assessed with nail psoriasis quality of life 10 scale.[5] Cutaneous disease severity was assessed with the help of psoriasis area severity index. Psoriatic arthritis was diagnosed based on the classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis and patients were diagnosed to be with (Group A) or without psoriatic arthritis (Group B).[6]

A complete hemogram and biochemical evaluation, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive proteins was done for all patients. In addition, serological assessment including evaluation of rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies was done with the help of commercially available kits following the manufacturers' instructions. C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor were assayed using RHELAX-CRP (Tulip Diagnostic, India [sensitivity of 0.6 mg/dl]) and RHELAX-RF (Tulip Diagnostic, Goa, India [sensitivity of 10 IU/ml]), respectively. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies were analyzed with a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay IMTEC-CCP-antibodies (IMTEC Human, Weisbaden, Germany).

The clinical and serological findings were recorded and correlated. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

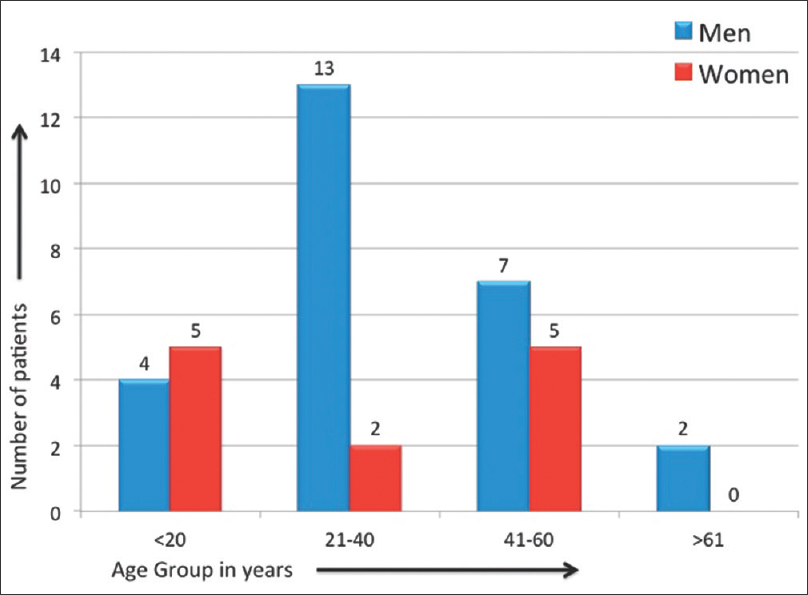

The mean age of our study population was 36.3 ± 14.7 years (range = 15–65 years). Overall, men twice outnumbered women (26 men vs. 12 women) [Figure - 1]. The reported duration of psoriasis ranged widely from 15 days to 31 years (mean = 21.6 ± 7.8 years). The cutaneous disease severity, as assessed by psoriasis area severity index, ranged from 0.4 to 34, with the mean being 14.4 ± 9.6.

|

| Figure 1: Age and sex distribution of the study population |

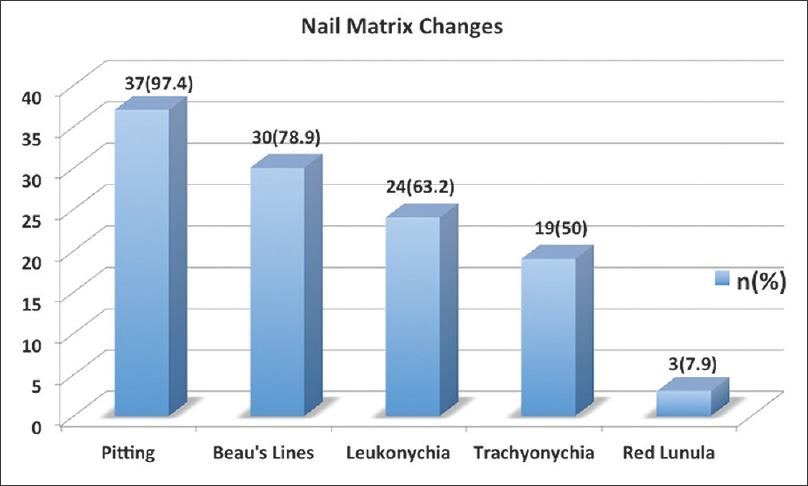

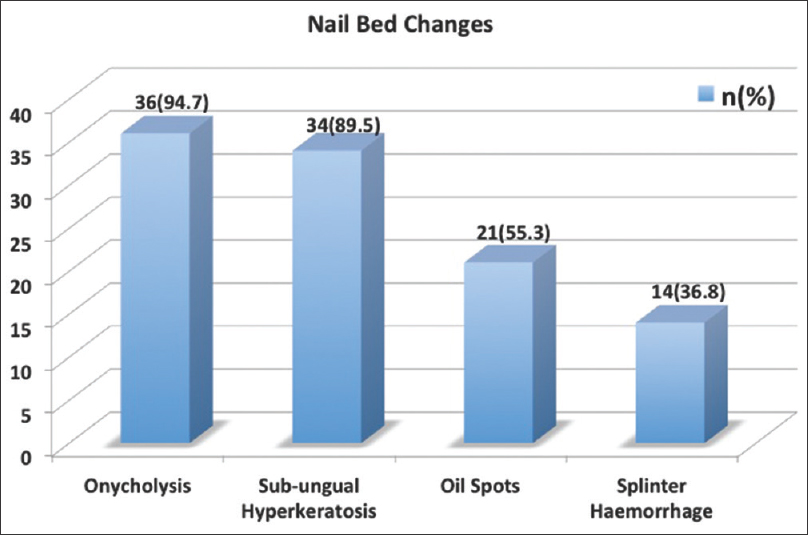

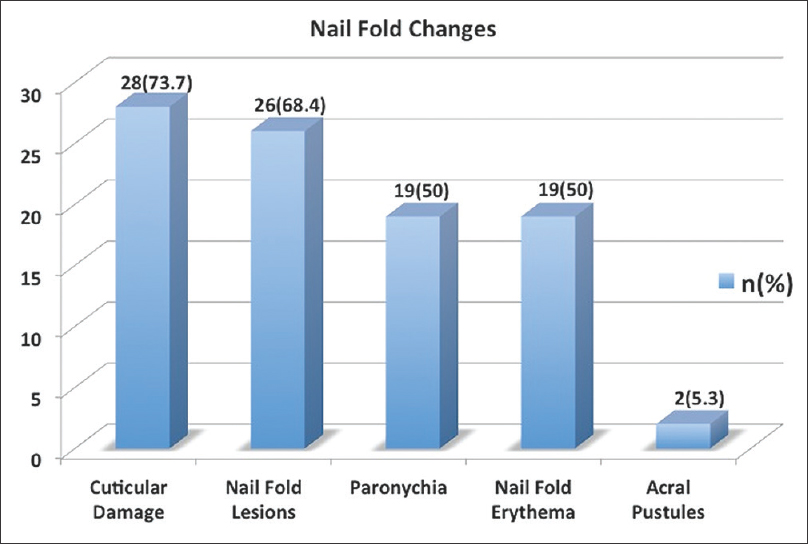

The nail changes in the cohort are outlined in [Figure - 2]. Among the nail matrix changes, the most common was pitting followed by Beau's lines and leukonychia [Figure 2a], whereas among the nail bed changes, the most common were onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis [Figure 2b]. Occurrence of acro-pustules and red lunula was very uncommon (two and three patients each, respectively). The presence of nail fold lesions was common and seen in 26/38 (68.4%) patients [Figure 2c].

|

| Figure 2a: Bar graph depicting the nail matrix changes |

|

| Figure 2b: Bar graph depicting the nail bed changes |

|

| Figure 2c: Bar graph depicting the nail fold changes |

The mean nail psoriasis severity index of the study cohort was 83.16 ± 40.077. The scores were marginally higher for the toenails than fingernails (42.61 ± 20.828 vs. 40.29 ± 21.048). Despite higher nail psoriasis severity index scores, the impact on quality of life as assessed by nail psoriasis quality of life 10 was low with a mean value of 1.1 ± 0.4. Furthermore, nail psoriasis severity index was higher in patients with concomitant arthritis, but the difference was not found to be significant.

Further analysis revealed that patients with nail fold lesions had a higher nail psoriasis severity index as compared to those lacking nail fold involvement (96.76 ± 36.11 vs. 54.58 ± 35.30; P = 0.002). Furthermore, the presence of oil spots was associated with a higher overall nail psoriasis severity index score as compared to patients without oil spots (101.48 ± 32.46 vs. 58.94 ± 38.22; P = 0.001).

Psoriasis area severity index showed a weakly positive but statistically insignificant correlation with nail psoriasis severity index (r = 0.26; P = 0.12), suggesting that with increase in cutaneous severity, the nail involvement also worsened. Nail psoriasis severity index and nail psoriasis quality of life 10 had a weakly positive correlation (Spearman's ρ = 0.375, P = 0.02), suggesting a worsening in quality of life with higher degree of nail affliction. Furthermore, the nail psoriasis quality of life 10 correlated well with the disease duration (Spearman's ρ = 0.481, P = 0.002), implying that the impact on quality of life worsened with an increase in disease duration.

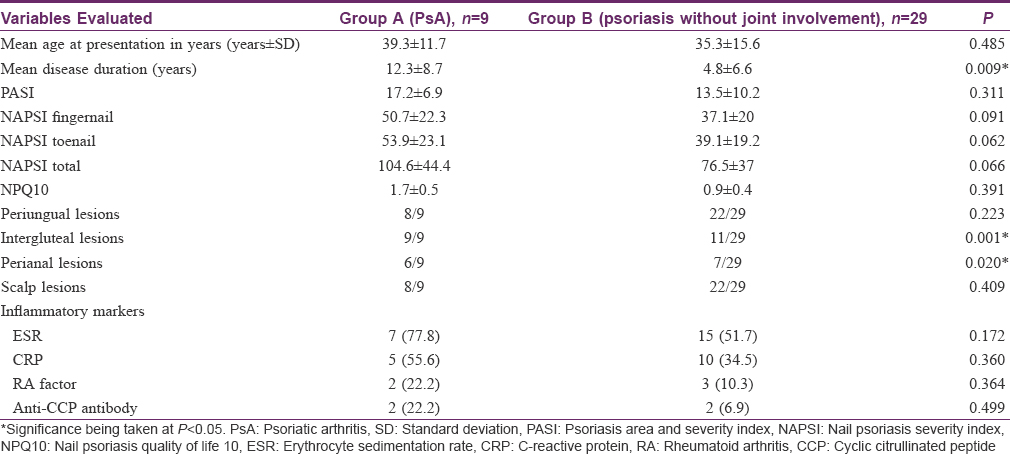

Subgroup analysis of the study subjects revealed that nine patients had evidence of joint involvement (Group A) as per the classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Of these, six patients had symmetrical polyarticular disease; two of which also had prominent axial skeletal involvement while rest of the three had asymmetrical oligoarticular disease. The baseline comparison of groups is highlighted in [Table - 1]. It was seen that the mean age of patients, mean disease duration, psoriasis area severity index, nail psoriasis severity index and nail psoriasis quality of life 10 scores, all were comparatively higher for Group A. In addition, there were certain site-specific variations between groups. Scalp involvement and presence of periungual lesions, intergluteal lesions and perianal lesions were notably higher in Group A (with psoriatic arthritis) as depicted in [Figure - 3].

|

| Figure 3: Bar graph demonstrating the difference in the prevalence of involvement of specific sites in the two subgroups, A and B (*P < 0.05) |

The hematological evaluation revealed anemia in 8/38 (21.1%) subjects; six of them had iron deficiency or combined nutritional deficiency anemia and the remaining two subjects had anemia of chronic disease with poor response to oral supplements. One of these two subjects had severe arthritis and required blood transfusion due to severe anemia. Liver functions were moderately deranged in two subjects. Renal parameters were normal in all patients, except for two patients with psoriatic arthritis who had episodic proteinuria and marginally elevated serum creatinine levels. One of these had nephrotic range proteinuria with membranous glomerulonephritis. All the patients were seronegative for hepatitis B, C and human immunodeficiency virus I and II.

The serological markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein were raised in 22/38 (57.9%) and 15/38 (39.5%) subjects, respectively. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies were found to be raised in 2/9 (22.2%) of psoriatic arthritis patients as compared to 2/29 (6.9%) of psoriasis without arthritis. Similarly, rheumatoid factor was positive in a higher proportion of patients with psoriatic arthritis (Group A) than Group B [Table - 1].

Discussion

Nail involvement in psoriasis is relatively less explored and often ignored, especially in the Indian setup. The present study evaluated clinical and serological profile of 38 psoriasis patients with nail involvement.

The most common clinical nail change in our series was found to be pitting followed by onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis [Figure - 2]. This finding is in concordance with earlier reported work.[7],[8] Nail fold lesions were found in a large proportion of our patients (26/38; 68.4%) and frequency was even higher in patients with psoriatic arthritis (8/9; 88.9%). Red lunula although considered to be less common in psoriasis was observed in 7.9% (3/38) subjects.

The mean nail psoriasis severity index scores vis-a-vis cutaneous severity were higher in our study as compared to previous studies both from India and elsewhere.[9],[10],[11],[12],[13] Higher nail psoriasis severity index scores in patients with concomitant arthritis are well known and are found in our study as well. We also observed that psoriasis area severity index showed a weak positive but statistically insignificant correlation with nail psoriasis severity index (r = 0.26; P = 0.12), demonstrating worsening of nail involvement with increased severity of skin disease.

Interestingly, although nails were considerably affected (overall high nail psoriasis severity index scores), the impact on quality of life (nail psoriasis quality of life 10 scores) was relatively low (mean 1.1 ± 0.4) in our study cohort. This is in contrast to Western studies documenting a higher impact on quality of life. Klaassen et al. reported mean nail psoriasis quality of life 10 score of 9.9 ± 14 in their study. This was also found to correlate with self-administered psoriasis area severity index.[13] This apparent discrepancy could be because most of the questions included in nail psoriasis quality of life 10 may not be particularly relevant to Indian patients. Majority of our patients belonged to lower socioeconomic strata with a good family/social support system found in many Indian joint families. Thus, a question analyzing their ability to drive a car stands irrelevant for the vast majority seeking care at a government-run tertiary care center. Similarly, when asking about ability to lock–unlock door, we realized that most of our patients did not have to do these so-called “daily activities” on their own because of a good support system. We found that many of our patients were even unaware of their nail disease or not bothered because it did not interfere with their daily living. Cosmesis also was not of much concern for most of our subjects. Probably, we need a more practical questionnaire suited to evaluate impact of nail psoriasis on the quality of life in Indian subjects.

Among clinical features, patients with psoriatic arthritis were commonly found to have intergluteal, perianal and periungual lesions of psoriasis [Figure - 3]. Involvement of these sites is also regarded as a predictor for the development of psoriatic arthritis.[14],[15] A closer follow-up and awareness regarding joint involvement in these patients may help in early diagnosis and efficient management. Periungual disease was also associated with higher nail psoriasis severity index scores.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease associated with an activation of a cascade of inflammatory mediators. Various markers of inflammation have been used to assess disease activity as well as response to treatment. The commonly used and easily available ones are c-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although both are assumed to be similar markers of inflammation, in reality they serve different purposes. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate rises slowly after an insult and also declines slowly after the stimulus is removed, remaining elevated for weeks thereafter. On the other hand, c-reactive protein has a shorter half-life (6–8 h) and is a marker of acute insult or inflammation. It also rapidly comes down with treatment. Thus, erythrocyte sedimentation rate is good for long-term monitoring, whereas c-reactive protein levels reflect day-to-day variation of disease activity.[16] C-reactive protein is a sensitive marker of inflammation although not specific.[17],[18] In a multicentric study, examining the characteristics of 1306 Italian patients with psoriatic arthritis, c-reactive protein was elevated in 52.6% of the cases.[19] Another study from India, documented raised c-reactive protein in 62% patients with psoriatic arthritis.[11] In our patients, c-reactive protein was raised in 15/38 (39.5%) of subjects and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was raised in 22/38 (57.9%).

Both rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are well-established markers of rheumatoid arthritis. The former has a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 85% for rheumatoid arthritis.[20] Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are antibodies against synthetic citrullinated peptides and are considered to be more specific marker for rheumatoid arthritis (specificity being 95%–96%) but with lower sensitivity (53%–68%).[21] van Gaalen et al. reported that 93% of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide positive patients with undifferentiated arthritis went on to develop rheumatoid arthritis over a 3-year of follow-up as compared to 25% of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide negative patients.[22]

Classically, psoriatic arthritis is a seronegative arthritis; however, rheumatoid factor may be positive in 10% patients, making psoriatic arthritis “usually seronegative.”[23],[24],[25],[26] Different studies have shown varying results with Böckelmann et al. reporting it positive in 8/62 (12.9%) patients,[27] whereas Shibata et al. reported it in 1/15 (7%) patients.[26] Other studies have reported rheumatoid factor positivity in 5%–19% of psoriatic arthritis patients.[22],[25],[27] However, there may be quantitative differences with serum levels of rheumatoid factor being higher in the patients with rheumatoid arthritis than in those with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. The present study found 5/38 (13.2%) patients to be rheumatoid factor positive. It was higher in patients with psoriatic arthritis (22.2%) as compared to those without arthritis (10.3%). Thus, our findings are in congruence with previous studies.

Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies have been reported to be varyingly elevated in patients with psoriasis.[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29] In patients with psoriatic arthritis, studies have documented positive anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in 5%–20% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.[23],[24],[25],[29],[30] These patients have been found to have more severe arthritis than seronegative patients. In psoriasis without arthritis, highly variable levels of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide have been reported; varying from as low as 0/15 (0%) patients [29] to as high as 11/62 (17.7%).[27] Our cohort had 4/38 (10.5%) positivity to anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody with 22.2% of psoriatic arthritis group being positive and only 6.9% of psoriasis without arthritis patients displaying positivity. In view of the highly variable results obtained in different studies, it is difficult to draw any definite conclusion as of now. We need more data from larger study populations.

Overall, patients with psoriatic arthritis demonstrated higher levels of inflammatory mediators such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein as well as serological markers such as rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. The inflammatory markers can be of help in following the course of the disease, whereas the serological markers may act as a hindrance to a definitive diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis as per existing diagnostic criteria. With an increase in our knowledge and awareness, one can remain open to a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis in undifferentiated seropositive arthritis, helping long-term treatment plans and prognosis.

Limitations

Our study was carried out on a relatively small cohort of patients with skin and nail involvement with psoriasis. Larger studies involving more numbers of patients of psoriasis with or without nail disease and/or joint disease can help clarify issues. Inclusion of matched controls from general population was also not done. If included in future works, this can help us clarify about the sensitivity and specificity of inflammatory and serological markers.

Conclusions

Our study documents nail changes in psoriasis and severity of involvement in the Indian context. We found discordance between the extent of nail involvement (as scored by nail psoriasis severity index) and the impact on quality of life (as evaluated by nail psoriasis quality of life 10). This lack of congruent impact suggests that probably the scoring systems need appropriate adaptation suited to the Indian population. Furthermore, a high proportion of patients had raised levels of immune and serological markers. Such reports in arthropathies other than rheumatoid arthritis raise a word of caution in their interpretation for diagnostic purposes. It can be seen that a close monitoring and follow-up of psoriatic patients with nail disease is of utmost importance. Further controlled studies with a larger population-based sample size are warranted before definite conclusions can be reached.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Scarpa R, Ayala F, Caporaso N, Olivieri I. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or psoriatic disease? J Rheumatol 2006;33:210-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Jiaravuthisan MM, Sasseville D, Vender RB, Murphy F, Muhn CY. Psoriasis of the nail: Anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature on therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:1-27.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Gladman DD, Chandran V. Psoriatic arthritis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill; 2012. p. 232-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Rich P, Scher RK. Nail psoriasis severity index: A useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:206-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Ortonne JP, Baran R, Corvest M, Schmitt C, Voisard JJ, Taieb C. Development and validation of nail psoriasis quality of life scale (NPQ10). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:22-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Tillett W, Costa L, Jadon D, Wallis D, Cavill C, McHugh J, et al. The classification for psoriatic arthritis (CASPAR) criteria – A retrospective feasibility, sensitivity, and specificity study. J Rheumatol 2012;39:154-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis: A questionnaire-based survey. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:314-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Grover C, Reddy BS, Uma Chaturvedi K. Diagnosis of nail psoriasis: Importance of biopsy and histopathology. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:1153-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Schons KR, Beber AA, Beck Mde O, Monticielo OA. Nail involvement in adult patients with plaque-type psoriasis: Prevalence and clinical features. An Bras Dermatol 2015;90:314-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Mukai MM, Poffo IF, Werner B, Brenner FM, Lima Filho JH. NAPSI utilization as an evaluation method of nail psoriasis in patients using acitretin. An Bras Dermatol 2012;87:256-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Kumar R, Sharma A, Dogra S. Prevalence and clinical patterns of psoriatic arthritis in Indian patients with psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014;80:15-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Rather S, Nisa N, Arif T. The pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Kashmir: A 6-year prospective study. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:356-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:1690-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: A population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:233-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Krensel M, Jacobi A, Reich K, Augustin M. Nail involvement as a predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:1123-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Kanelleas A, Liapi C, Katoulis A, Stavropoulos P, Avgerinou G, Georgala S, et al. The role of inflammatory markers in assessing disease severity and response to treatment in patients with psoriasis treated with etanercept. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011;36:845-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Chodorowska G, Wojnowska D, Juszkiewicz-Borowiec M. C-reactive protein and alpha2-macroglobulin plasma activity in medium-severe and severe psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004;18:180-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Coimbra S, Oliveira H, Reis F, Belo L, Rocha S, Quintanilha A, et al. C-reactive protein and leucocyte activation in psoriasis vulgaris according to severity and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:789-96.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Cervini C, Leardini G, Mathieu A, Punzi L, Scarpa R. Psoriatic arthritis: Epidemiological and clinical aspects in a cohort of 1.306 Italian patients. Reumatismo 2005;57:283-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Kawano S, et al. Meta-analysis: Diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:797-808.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Taylor P, Gartemann J, Hsieh J, Creeden J. A systematic review of serum biomarkers anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor as tests for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmune Dis 2011;2011:815038.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

van Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, de Jong BA, Breedveld FC, Verweij CL, et al. Autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:709-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Bogliolo L, Alpini C, Caporali R, Scirè CA, Moratti R, Montecucco C. Antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:511-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Vander Cruyssen B, Hoffman IE, Zmierczak H, Van den Berghe M, Kruithof E, De Rycke L, et al. Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies may occur in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1145-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Inanc N, Dalkilic E, Kamali S, Kasapoglu-Günal E, Elbir Y, Direskeneli H, et al. Anti-CCP antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:17-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Shibata S, Tada Y, Komine M, Hattori N, Osame S, Kanda N, et al. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and IL-23p19 in psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol Sci 2009;53:34-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Böckelmann R, Gollnick H, Bonnekoh B. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in psoriasis patients without arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1701-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Punzi L, Podswiadek M, Oliviero F, Lonigro A, Modesti V, Ramonda R, et al. Laboratory findings in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo 2007;59 Suppl 1:52-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Candia L, Marquez J, Gonzalez C, Santos AM, Londoño J, Valle R, et al. Low frequency of anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in psoriatic arthritis but not in cutaneous psoriasis. J Clin Rheumatol 2006;12:226-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Maejima H, Aki R, Watarai A, Shirai K, Hamada Y, Katsuoka K. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide in Japanese psoriatic arthritis patients. J Dermatol 2010;37:339-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,174

PDF downloads

1,626