Translate this page into:

Clinico-histopathological review of cutaneous sarcoidosis: A retrospective descriptive study

Corresponding author: Dr. Sujay Khandpur, Department of Dermatology & Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. khandpursujay@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Chandra AD, Khandpur S, Ramam M, Bhari N, Gupta V, Agarwal S. Clinico-histopathological review of cutaneous sarcoidosis: A retrospective descriptive study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_368_2024

Abstract

Background

Sarcoidosis is a systemic, non-caseating granulomatous disease characterised by clinical and histopathological variability.

Objective

To review cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis and describe their clinical and histopathological features.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted to analyse the clinical and histopathological frecords of all available skin biopsy slides signed out as ‘sarcoidal tissue reaction’ or ‘sarcoidosis’ from 2014 till 2022.

Results

A total of 25 cases were studied. The lesions were most commonly located on the head and neck (18 cases, 72%). Morphologically plaques (20%) were the most common, and the majority of cases had lesions of ≥2 distinct morphologies (44%). Histologically, classical naked granulomas were observed in 72% of cases. The granulomatous infiltrate was pandermal in 56% of cases, perivascular and interstitial in 16%, and perivascular, perieccrine, and interstitial in 12%. Granulomas with a ‘leprosy’ pattern were observed in 20% of cases. High-density granulomas (occupying >30% of the dermis) were present in 64% of cases. Fibrinoid necrosis and fibrosis between granulomas were observed in 16% and 8% cases, respectively. Inclusion bodies, such as asteroid and Schaumann bodies, were seen in 24% and 4% cases, respectively. Reticulin-rich granulomas were observed in 54% cases, while reticulin-poor granulomas were seen in 8.3%. Elevated serum ACE levels were found in 14 cases, and tuberculin skin test, conducted in 22 cases, was negative. Extracutaneous involvement was found in 11 cases, with 10 having pulmonary and 1 with pulmonary and splenic involvement.

Limitation

Retrospective nature of the study and small sample size.

Conclusion

Cutaneous sarcoidosis presents with a wide range of clinical and histomorphological features, necessitating clinico-histopathological correlation and ancillary investigations to establish the diagnosis and rule out mimickers.

Keywords

Sarcoidosis

granulomas

histopathology

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic, non-caseating granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology. Although it may affect several organs; the lungs, lymph nodes, and skin are primarily involved.1 Dermatologists encounter sarcoidosis with a myriad morphologies, including specific and non-specific lesions. Specific lesions include papules, plaques, annular lesions, lupus pernio, and subcutaneous nodules. Histopathologically, specific lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis are characterised by the presence of sarcoidal granulomas, which are discrete, monomorphic, round to oval collections of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, surrounded by a sparse rim of peripheral lymphocytes (naked tubercles).2 Many non-specific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, calcinosis, erythema multiforme-like lesions, or pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions develop due to a reactive process without the formation of granulomas.3 Clinicians often use the term ‘sarcoidosis’ to denote the generalised disease, while pathologists who observe only a localised lesion on biopsy, frequently prefer the term ‘sarcoid’ or ‘sarcoidal tissue reaction’.4 Since this reaction pattern is encountered in several dermatoses, with sarcoidosis being the prototype, various international societies working on this group of disorders suggest diagnosing sarcoidosis if the following criteria are fulfilled: a compatible clinical picture, histologic demonstration of non-caseating granulomas, and exclusion of other diseases capable of producing a similar clinical picture.5 In the Indian setting, there is a paucity of studies on cutaneous sarcoidosis. Hence, we conducted a retrospective, descriptive study on the clinico-histopathological features of this dermatosis.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study in the Departments of Dermatology and Pathology at a tertiary care hospital, after approval from the institutional ethics committee (Ref. no. IECPG-698/23.12.2020). We reviewed the records of all available skin biopsy slides signed out as ‘sarcoidal tissue reaction’ or ‘sarcoidosis’ from January 2014 to June 2022 and performed a clinico-histopathological correlation of cases with a clinical diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (with or without systemic involvement) who had received treatment. The patients included were those who gave informed consent and either visited our hospital for review with previous prescriptions and images or provided information about their medical condition including clinical photographs, on the phone. Skin biopsy slides were screened for adequacy and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), reticulin, and other special stains (as required), and were also polarised. Clinical and histopathological features were recorded in a pre-designed proforma. Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics including mean, median and range for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

Results

We identified 48 slides with a histopathological diagnosis of ‘sarcoidal tissue reaction’ or ‘sarcoidosis’. Of these, clinical data for 25 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis could be reviewed.

Clinical characteristics

Among the 25 patients, there was a slight female preponderance (56% females vs 44% males). The mean age onset was 39 ± 16.0 years, with a mean disease duration of 28.2±30.2 months {median-18 months (range: 6–108 months)}. Family history of sarcoidosis was negative in all cases.

The majority of the cutaneous lesions were located on head and neck (18 cases) [Figure 1a], while 10 patients had lesions on the trunk [Figure 1b], upper limbs [Figure 1c], or multiple sites, and 4 had lesions on the lower limbs. The predominant morphology was plaques (5 cases, 20%) [Figure 2a], with the majority (11 cases, 44%) having lesions with two or more morphologies [Figure 2b]. Papules, nodules, annular, or telangiectatic plaques were observed in 2 cases (8%) each, and macular lesions were observed in 1 case. Surface changes included epidermal atrophy in 6 cases (24%), and telangiectasia and scaling in 2 cases (8%) each. A conspicuous hypopigmented halo around the lesions was present in 20% of the cases [Figure 2c]. The clinical characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

- (a) Erythematous infiltrated confluent plaques on the right side of the face, involving the right ear. (b) Discrete erythematous plaques on the abdomen (white arrows). (c) Multiple discrete to confluent erythematous papules and plaques on the forearm.

- (a) Oedematous shiny skin-coloured plaques overlying scars from a previous injury. (b) Multiple erythematous papules (white arrow) and plaques (yellow arrow) on the face. (c) Discrete erythematous to brown papules and plaques with a perilesional hypopigmented halo (white arrow).

| Clinical characteristics | Cases (n=25) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 (44%) |

| Female | 14 (56%) |

| Age of patients (years) | |

| Mean | 43.7 ± 50.5 |

| Median | 50.5 (21-74) |

| Age at onset of disease | |

| Mean (years) | 39 ± 16.0 |

| Median | 45.3 (19.5-73.5) |

| Duration of disease (in months) | |

| Mean | 28.2 ± 30.2 |

| Median | 18 (6-108) |

| Treatment taken before contacting us. | |

| Yes | 20 (80%) |

| - Sarcoidosis-specific | 13 (65%) |

| Topical steroids/ tacrolimus | 11 |

| Oral steroids | 2 |

| Not known | 7 |

| Treatment naive | 5 (20%) |

| Location of lesions | |

| Head & neck | 18 |

| Upper limb | 10 |

| Lower limb | 4 |

| Trunk | 10 |

| ≥2 sites (combination of above sites) | 10 |

| Lesion morphology | |

| Papules | 2 (8%) |

| Plaques | |

| Classical plaques | 5 (20%) |

| Annular plaques | 2 (8%) |

| Telangiectatic plaques | 2 (8%) |

| Nodules | 2 (8%) |

| Macules | 1 (4%) |

| ≥2 morphologies (combination of above morphologies) | 11 (44%) |

| No. of lesions | |

| 1 | 2 (8%) |

| 2-5 | 4 (16%) |

| 6-10 | 6 (24%) |

| >10 | 13 (52%) |

| Size of the lesions | |

| <1 cm | 12 |

| 1 to 3 cm | 24 |

| >3 cm | 9 |

| Symmetry | |

| Unilateral | 6 (24%) |

| Bilateral, symmetrical | 0 |

| Bilateral, asymmetrical | 19 (76%) |

| Midline | 0 |

| Symptoms | |

| Asymptomatic | 21 (84%) |

| Pruritic | 3 (12%) |

| Pain | 1 (4%) |

| Colour of lesions | |

| Erythematous | 17 (68%) |

| Hypopigmented | 1 (4%) |

| Skin-coloured | 1 (4%) |

| Erythematous to skin-coloured | 6 (24%) |

| Any surface changes | |

| Epidermal atrophy | 6 (24%) |

| Telangiectasia | 2 (8%) |

| Scaling | 2 (8%) |

| None | 15 (60) |

| Hypopigmented halo around lesions | |

| Present | 5 (20%) |

| Absent | 20 (80%) |

Histopathological features

Epidermal changes

Of the cases with epidermal involvement (17, 68%), atrophic epidermis was observed in 9 (36%), follicular plugging in 5 (20%) [Figure 3a], acanthosis in 2 (8%), and parakeratosis in 1 (4%). A well-formed grenz zone was present in 3 cases (12%) [Figure 3b].

- Epidermal changes: (a) Cutaneous sarcoidosis showing prominent follicular plugging (black arrow) (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x). (b) Cutaneous sarcoidosis showing a narrow grenz zone (double-headed arrows) (Haematoxylin and eosin, 40x).

Dermal changes

High-density sarcoidal granulomas, that is, granulomas occupying >30% of the dermis were found in 16 cases (64%). Moderate-density granulomas, occupying 10- 30% of the dermis, were present in 5 cases (20%), and mild-density granulomas, occupying <10% of the dermis, were seen in 4 cases (16%).

Regarding the location of granulomas, they were present in the entire dermis diffusely in 8 cases (32%). Other patterns seen were: pandermal with discrete involvement in 5 cases (20%), occupying mid and deep dermis in 4 cases (16%), superficial and mid dermis in 3 cases (12%), superficial and deep dermis in 2 cases (8%), and dermal involvement with subcutaneous extension in 3 cases (12%) [Figure 4a].

- (a) Well-circumscribed to coalescent granulomas present throughout the dermis with subcutaneous extension (Haematoxylin and eosin, 20x). (b) Band-like distribution of granuloma in the upper dermis with perifollicular extension (black arrow) (Haematoxylin and eosin, 40x).

In cases without discrete granulomas, the distribution of the granulomatous infiltrate was pandermal in 14 cases (56%), perivascular and interstitial in 4 cases (16%), and perivascular, perieccrine, and interstitial in 3 cases (12%). Perifollicular location of granulomas was observed in 1 case (4%) [Figure 4b]. Interestingly, we observed granulomas distributed in a ‘leprosy’ pattern (superficial, and deep, discrete, oval, oblong, and curvilinear configuration of granulomas) in 5 cases (20%) [Figure 5].6

- Sarcoidal granulomas oriented in leprosy pattern, showing superficial and deep, discrete, oval, oblong, and curvilinear well-circumscribed configuration of granulomas (Haematoxylin and eosin, 40x).

The majority of cases, granulomas contained giant cells, with Langhans- type observed in 21 cases (84%), and foreign body type of giant cells in 15 cases (60%) [Figure 6].

- Numerous Langhans-type giant cells (black arrow) and foreign body giant cells (yellow arrow) present within the sarcoidal granulomas (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x).

The classic feature of a sarcoidal granuloma is a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate rimming the granulomas, which was observed in 18 cases (72%) [Figure 7]. Interestingly, a moderate density of lymphocytes, that is approximately equal to granuloma density, was seen in 6 cases (24%), while a dense lymphocytic infiltrate around the granulomas, that is, lymphocyte density more than granuloma density, was noted in 1 case (4%) [Figure 8a].

- Pandermal distribution of discrete granulomas in the superficial, mid, and deep dermis with surrounding pauci-cellular infiltrate (Haematoxylin and eosin 40x).

- (a) Dense lymphocytic infiltrate (black arrows) around the sarcoidal granulomas (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x). (b) Presence of eosinophils (black arrows) among the granulomatous infiltrate (Haematoxylin and eosin, 400x). (c) Presence of foamy histiocytes (arrow) within the granulomatous infiltrate (Haematoxylin and eosin, 400x).

Admixed with the sarcoidal granulomas, other cell types were observed, including eosinophils in 7 cases (28%) [Figure 8b], plasma cells in 3 cases (12%), and foamy histiocytes in 1 case (4%) [Figure 8c].

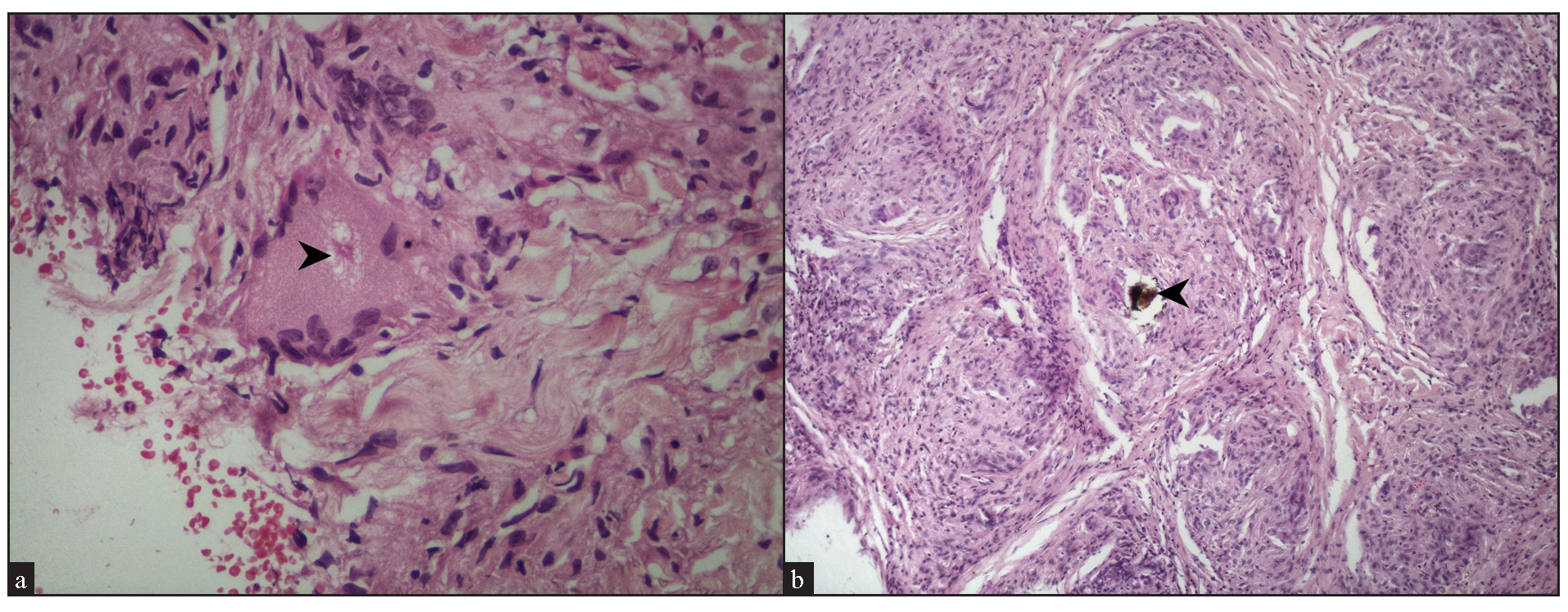

We observed fibrinoid necrosis within the granulomas in 4 cases (16%) [Figure 9a]. Fibrosis between the granulomas was seen in 2 cases (8%) [Figure 9b]. Inclusion bodies, such as asteroid bodies [Figure 10a] and Schaumann bodies [Figure 10b] were seen in 6 cases (24%) and 1 case (4%), respectively. Interestingly, one case showed basophilic homogenous material within giant cells, attributed to triamcinolone acetonide deposited following multiple intralesional injections. Significant dermal oedema was noted in 4 cases (16%).

- (a) Fibrinoid type of necrosis (arrow) seen in the granuloma (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x). (b) Fibrosis (black arrow) encircling the granuloma (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x).

- (a) Asteroid body (black arrowhead) within a giant cell (Haematoxylin and eosin, 400x). (b) Schaumann body (black arrowhead) with a giant cell in a sarcoidal granuloma (Haematoxylin and eosin, 100x).

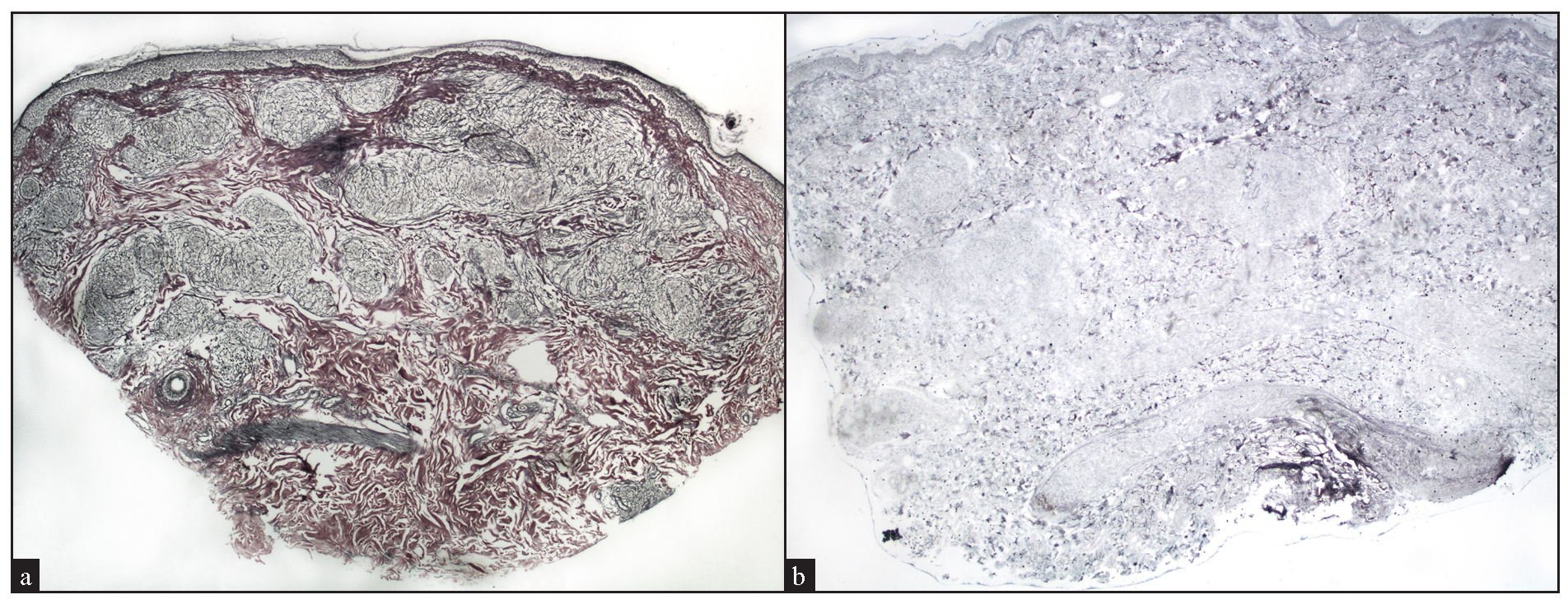

Reticulin stained slides was available for 24 cases, with 13 cases (54%) showing reticulin-rich granulomas [Figure 11a], and 2 cases (8.33%) showing reticulin-poor granulomas [Figure 11b].

- (a) Preservation of reticulin fibers within well-circumscribed granulomas, indicating reticulin-rich sarcoidal granulomas (Reticulin stain, 20x). (b) Absence of reticulin fibers within well-circumscribed granulomas, indicating reticulin-poor sarcoidal granulomas (Reticulin stain, 40x).

The histopathological features are summarised and compared with previous studies in Table 2.

| Histopathological finding |

Cardoso et al.8 (n=30) |

Ishak et al.9 (n=76) |

Mahabal et al.7 (n=38) |

García-Colmenero et al.13 (n=48) |

Tiago C et al.14 (n=42) |

Our study (n= 25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermal change | ||||||

| Atrophy | 17 (55%) | 26 (32%) | NR+ | 5 (10.4%) | 13 (31%) | 9 (36%) |

| Parakeratosis | 8 (26%) | 8 (10%) | NR | NR | NR | 1 (4%) |

| Acanthosis | 3 (10%) | 1 (1%) | NR | 6 (12.5%) | 11 (26.2%) | 2 (8%) |

| Basal cell damage | NR | NR | NR | 6 (12.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 |

| Follicular plugging | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 (20%) |

| Hyperkeratosis | NR | NR | NR | 2 (4%) | NR | NR |

| Grenz zone | NR | 5 (6%) | NR | 16 (33.3%) | 20 (47.6%) | 3 (12%) |

| Dermal findings | ||||||

| 1. Density of granulomatous infiltrate | ||||||

| Mild | 6 (19%) | 8 (10%) | NR | NR | 10 (23.8%) | 4 (16%) |

| Moderate | 14 (45%) | 37 (46%) | NR | NR | 17 (40.5%) | 5 (20%) |

| High | 11 (36%) | 36 (44%) | NR | NR | 15 (35.7%) | 16 (64%) |

| 2. Location of sarcoidal granulomas | ||||||

| Superficial dermis | 5 (16%) | 4 (5%) | 11 (29%) | 21 (43.8%) | 6 (14.3%) | 1 (4%) |

| Superficial +mid dermis | 9 (29%) | 9 (11%) | NR | NR | 16 (38.1%) | 3 (12%) |

| Superficial + deep dermis | NR | 65 (80%) | NR | NR | NR | 2 (8%) |

| Mid dermis | NR | NR | 10 (26.4%) | NR | 5 (11.9%) | NR |

| Mid + deep dermis | 10 (32%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4 (16%) |

| Deep dermis | NR | NR | 8 (21%) | 34 (70.8%) | NR | 2 (8%) |

| Entire dermis (diffuse) | 7 (23%) | NR | NR | NR | 13 (30.9%) | 8 (32%) |

| Entire dermis (discrete) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 (20%) |

| Subcutaneous extension | NR | 16 (20%) | 9 (23.6%) | 20 (41.7%) | 2 (4.8%) | 3 (12%) |

| 3. Topographical distribution of sarcoidal granulomas | ||||||

| Perivascular + Interstitial | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4 (16%) |

| Perivascular + Perieccrine + Interstitial | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3(12%) |

| Perivascular + Perifollicular + Interstitial | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1(4%) |

| Band-like + Perifollicular | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1(4%) |

| Perifollicular + Perieccrine + Interstitial | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1(4%) |

| Pandermal discrete interstitial distribution | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3(12%) |

| Pandermal diffuse interstitial location | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11 (44%) |

| Perivascular | 4 (13%) | 54 (66%) | 9 (23.6%) | 24 (50%) | 3 (7.1%) | NR |

| Perineural | 4 (13%) | 15 (23%) | 1 (2.6%) | 6 (12.5%) | NR | NR |

| Peri-adnexal | 10 (32%) | 13 (16%) | 8 (21%) | 15 (31.3%) | 4 (9.5%) | 1 (4%) |

| Interstitial | 5 (16%) | 17 (33%) | 19 (50%) | NR | 28 (66.7%) | NR |

| 4. Cell types | ||||||

| Giant cells | 30 (97%) | 73 (90%) | 36 (94.7%) | 46 (95.8%) | 41 (97.61%) | 23 (92%) |

| - Langhans type | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 21 (84%) |

| - Foreign body type | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 15 (60%) |

| Lymphocyte density | ||||||

| + (sparse) | NR | 71 (88%) | NR | 32 (66.7%) | absent: 17, | 18 (72%) |

| ++ (moderate) | NR | 8 (10%) | NR | 11 (22.9%) | few:25 | 6 (24%) |

| +++ (severe) | NR | 2 (2%) | NR | 1 | 1 (4%) | |

| Plasma cells | 1 (3%) | 42 (52%) | 12 (31.5%) | NR | NR | 3 (12%) |

| Eosinophils | NR | 4 (5%) | 0 | NR | NR | 7 (28%) |

| Foamy histiocytes | NR | 15 (19%) | NR | NR | NR | 1 (4%) |

| Neutrophils | 1 (3%) | NR | 3 (7.8%) | NR | NR | NR |

| 5. Orientation of granuloma | ||||||

| Vertical | 7 (23%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4 (16%) |

| Horizontal | 19 (61%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 (28%) |

| Vertical + Horizontal | 4 (13%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 13 (52%) |

| Cannot be commented | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 (4%) |

| Erythema annulare centrifugum-like | 1 (3%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 6. Other features | ||||||

| Necrosis (Fibrinoid type) | 2 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (15.7%) | 13 (27%) | NR | 4 (16%) |

| Fibrosis | 3 (10%) | 1 (1%) | NR | 9 (18.8%) | NR | 2 (8%) |

| Deposits/ foreign body | 4 (13%) | 8 (10%) | 5 (13.1%) | 5 (10.4%) | 10 (23.8%) | 1 (4%) |

| Asteroid body/Schaumann body | 10 (32%) | NR | NR | 1 (2%) | 3 (7.2%) | 7 (28%) |

| Calcification | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Tuberculoid granulomas | NR | 6 (7%) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mucin | NR | NR | 2 (5.2%) | NR | NR | NR |

| 7. Leprosy pattern of distribution of granulomas | ||||||

| Present | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 (20%) |

| 8. Reticulin staining | ||||||

| Reticulin rich | NR | NR | 19/23 (82%) | NR | NR | 13 (52%) |

| Reticulin poor | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 (8%) |

| Rich to poor | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 (20%) |

| Poor to rich | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4 (16%) |

| Slide not available to comment | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 |

+NR- Not reported

Laboratory findings

Haematological investigations were normal in all 25 cases. The mean calcium level was 9.51 ± 0.66 mg/dL (reference value: 8.5-10.5 mg/dl). Serum calcium levels were normal in 23 cases (92%), while one case each had a high (11.9 mg/dL) and a low (8.3 mg/dL) level. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were available for 23 cases, of which 14 (61%) had elevated levels. The tuberculin skin test conducted in 22 cases was negative in all. Chest X-ray was available for 24 cases, with abnormal findings reported in 7 (28%). Of these, 6 (24%) were suggestive of sarcoidosis, including mediastinal lymphadenopathy (3 cases) and reticular opacities (3 cases), and one case exhibited pneumothorax along with patchy consolidation in both upper lobes, suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis. However, high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) of the chest findings favoured pulmonary sarcoidosis in the last patient as well. HRCT of the chest was available for 13 cases, with abnormal findings seen in 10 cases (76.92%). Of these, 9 cases were reported as pulmonary sarcoidosis, while one case had interstitial lung disease. Pulmonary function tests were available for 10 patients, showing a restrictive pattern in 4 cases (40%), while it was normal in 6 cases (60%). One case had splenic involvement confirmed by HRCT. Fundoscopy performed in 18 cases was normal in all. Of the 18 cases where an electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed, 17 showed normal results. However, in one case, a right ventricular strain pattern was detected, which was attributed to hypertension. Echocardiography performed in 4 cases revealed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in the hypertensive individual, while the other 3 exhibited normal results.

Final diagnosis

Of the 25 cases of sarcoidosis studied, 14 (56%) had cutaneous sarcoidosis without extracutaneous involvement.Among these, papules and plaques in combination, were the most common cutaneous morphology (3 cases) and 3 cases had only plaques. Papular and nodular forms of sarcoidosis were each observed in two cases, while hypopigmented, angiolupoid, annular, and scar sarcoidosis were seen in one case each.

Extracutaneous involvement was detected in 11 cases (44%). Of these, 10 had only pulmonary involvement, while one case had pulmonary with splenic involvement. Among the 10 cases with concomitant pulmonary sarcoidosis, the cutaneous morphologies included a combination of papules and plaques, and plaques alone in 3 cases each, and papules, annular plaques, and nodules in one case each. The case with both pulmonary and splenic involvement presented with papular sarcoidosis.

Discussion

This was a retrospective study aimed at assessing the clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The mean age at disease onset was 39±16 years, which is lower than that reported by Mahabal et al.7 A female preponderance of cutaneous sarcoidosis, as noted in our series (56% females), was concordant with findings from other studies.7-10

In our study, the most common morphologies observed were papules with plaques or plaques alone (6 cases each), followed by papules (4 cases), nodules (3 cases), annular plaques (3 cases), hypopigmented, angiolupoid and scar sarcoidosis (one case each). In a study by Cardoso et al., most common morphologies were papules and plaques followed by nodules.8 Ishak et al observed plaques, papules, nodules, lupus pernio, and lesions with at least two different morphologies.9 Mahabal et al. reported plaques, papules, nodules, depigmented macules, psoriasiform lesions, scar sarcoidosis, and angiolupoid lesions as the main morphologies.7 In an Indian study, Mahajan et al., found that lesions with >2 morphologies were the most common presentation, followed by nodules, plaques papules, scar sarcoidosis, and angiolupoid sarcoid.10

In our study, the predominant locations of cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions were the head and neck (18 cases), upper limbs (10 cases), trunk (10 cases), multiple sites (10 cases), and lower limbs (4 cases). Ishak et al. also observed lesions on the head and neck followed by at least two different anatomical sites, including the arms, legs, and trunk.9 Some studies have shown lower limbs and trunk to be the most common sites of involvement.7,8 Most of our cases (52%) had >10 lesions. Mahabal et al. also observed multiple, that is, ≥4 lesions in 74% of the cases.7 In the present study, there was no correlation observed between the number and location of the lesions and extracutaneous involvement.

The majority of lesions in the present patients were erythematous (68% cases), with no surface changes in 60% cases and with epidermal atrophy in 24% of cases. Scaling and telangiectasia were observed in 8% cases each in the others. Conspicuously, a hypopigmented halo around the lesions was present in 20% of our cases, which we think is an important differentiating feature from other granulomatous dermatoses. A morphological variant presenting as erythematous lesions within hypopigmented patches and attributed to interface dermatitis has been reported in cutaneous sarcoidosis. However, this histological feature was not seen in the present cases with the hypopigmented halo.11

On histopathological assessment of the patients, epidermal involvement was observed in majority (68%) of the cases, which included epidermal atrophy (36%), follicular plugging (20%), acanthosis (8%), and parakeratosis (4%). Hyperkeratosis, which was not observed in the cases, has been reported in the literature.12 A grenz zone, noted in 12% of the cases, has also been reported in other studies.13,14

The granulomas in the patients mostly occupied the entire dermis, either diffusely (32% cases) or in a discrete manner (20%), although other patterns of dermal involvement were also observed. Cardoso et al. reported granulomas mainly in the mid and deep dermis, followed by superficial and mid-dermis, while Ishak et al. found both superficial and deep dermal involvement by granulomas in the majority of their cases.8,9 We did not find any differences in the depth, density, and location of the granulomas between the cases of different morphologies in our study, including macules, papules, plaques, nodules, or scar.

Sarcoidal granulomas were interstitially located in most of our cases, with some instances showing perivascular, perieccrine, and perifollicular localisation. The interstitial distribution of granulomas, also seen in conditions such as interstitial granulomatous dermatitis or granuloma annulare, can pose a diagnostic challenge in such instances.15,16 Ishak et al. reported perivascular location of granulomas most frequently in their sarcoidosis cases, followed by interstitial, perineural, and periadnexal location.9 In our series, perineural granulomas were not observed, though this feature was observed in a few previous sarcoidosis biopsies by us. This highlights the fact that a perineural granulomatous infiltrate is not unique to leprosy but can also be seen in other dermatoses, including sarcoidosis.

In our study, the density of lymphocytes around the granulomas was sparse in most instances (72%), which is consistent with the conventional findings in sarcoidosis. Interestingly, a moderate density of lymphocytes around granulomas was observed in 24% of cases, while one case showed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate around the sarcoidal granulomas, clinically manifesting as papular sarcoidosis. Variable density of lymphocytes around granulomas has also been observed in other series.8,13-14

We observed small foci of fibrinoid necrosis within the granulomas in 4 cases (16%). Although sarcoidosis typically shows non-necrotising granulomas, focal necrosis within granulomas has been described in otherwise typical cases in 1-27% studies, suggesting that this may not be an exceptional finding.7-9,13,15 In fact, even caseous necrosis, a usual finding in infective pathologies such as cutaneous tuberculosis or leishmaniasis, has been described in rare instances of cutaneous sarcoidosis.17 Fibrosis, observed in 8% of the cases, has also been reported in other studies in 1-18% of patients.8,9,13 Foreign material within giant cells has been described in 22–77% of cutaneous sarcoidosis biopsies, whereas only one of our patient with scar sarcoidosis showed polarizable foreign material. There is a greater likelihood of finding foreign material in lesions located at injury sites, suggesting that foreign substances may serve as a nidus for granulomatous reaction.16

Although inclusion bodies within giant cells are important in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, they can also be observed in granulomas of different etiologies. We found asteroid and Schaumann bodies in 24% and 4% cases, respectively. Asteroid bodies have been reported by various studies in 2- 23.5% of cutaneous sarcoidosis.13-14,18

We observed sarcoidal granulomas arranged in typical ‘leprosy pattern’ in 20% cases, making it histopathologically difficult to differentiate from tuberculoid leprosy, and requiring clinical correlation. A case of borderline tuberculoid leprosy histologically mimicking sarcoidosis has been reported.19 Interestingly, there are case reports of the co-existence of leprosy and sarcoidosis in the same patients.20-21

Conventionally, sarcoidal granulomas are reticulin-rich due to preserved reticulin fibers, whereas granulomas in infectious conditions are typically reticulin-poor. In our study, although over half the cases (54%) had preserved reticulin fibers, 8.3% cases showed all reticulin-poor granulomas, and 16% of cases had predominantly reticulin poor granulomas. Mahabal et al. described reticulin-rich granulomas in 82% of their sarcoidosis cases.7 Other reticulin-staining patterns have not been highlighted in the literature for comparison.

Conclusion

Cutaneous sarcoidosis presents with a diverse range of clinical and histomorphological features, requiring clinico-pathological correlation in addition to other investigations. Often it also needs assessment based on response to sarcoidosis treatment in order to establish the diagnosis and differentiate it from similar histopathological mimickers.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, number IECPG-698/23.12.2020, dated 23/12/2020.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Sarcoidosis: A comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: Part I. Cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-18. quiz 717-8

- [Google Scholar]

- The granulomatous reaction pattern. In: Weedon D, ed. Skin Pathology (5th ed). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2015. p. :212-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sarcoidosis of the skin: A review for the pulmonologist. Chest. 2009;136:583-596.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epithelioid cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatopathology Diag Dermatol. 2018;5:7-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis: A retrospective clinico-pathological study from the Indian subcontinent in patients attending a tertiary health care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:566-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis: A histopathological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:678-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis: Clinicopathologic study of 76 patients from Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:33-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis: Clinical profile of 23 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:16-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41:e355-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic value of skin lesions in sarcoidosis: Clinical and histopathological clues. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:556-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 32 cases of specific cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:772-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: A study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:160-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subcutaneous sarcoidosis with extensive caseation necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:188-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and histopathological analysis of specific lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis in Korean patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:11-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borderline tuberculoid leprosy mimicking sarcoidosis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11616.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Leprosy or sarcoidosis? A diagnostic dilemma! J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:1106-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systemic sarcoidosis in a case of lepromatous leprosy: A case report. Indian J Lepr. 2008;80:275-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]