Translate this page into:

Congenital chikungunya infection presenting with extensive dystrophic calcinosis cutis

2 Department of Pediatrics, Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Correspondence Address:

Sahana M Srinivas

Department of Pediatric Dermatology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bengaluru, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Srinivas SM, Pradeep G C. Congenital chikungunya infection presenting with extensive dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2020;86:693-696 |

Sir,

Congenital chikungunya infection presenting at birth is rare and poses a diagnostic challenge. We describe a newborn with congenital chikungunya infection presenting with extensive dystrophic calcification.

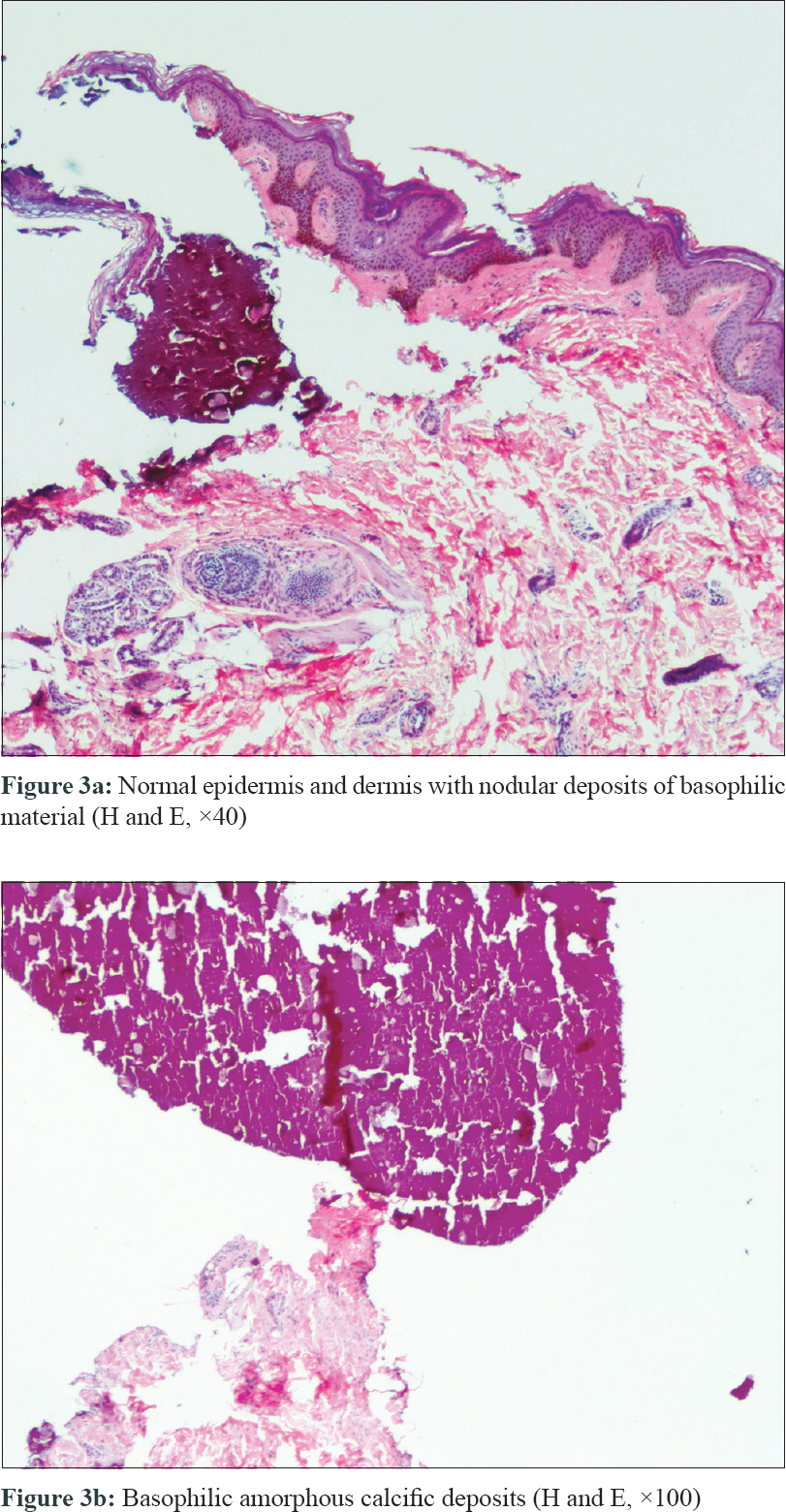

An 11-days-old full term, male child born of non-consanguineous marriage presented with multiple ulcers all over the body since birth. On day one of life, the child developed fever and poor feeding, and was presumed to have sepsis. He had ill-defined hyperpigmented macules on face and trunk along with exfoliation over the extremities [Figure - 1]. There was history of fever without joint pain in the mother during eighth month of pregnancy which resolved spontaneously in 2 days without treatment. The cause of fever was not established. However, there was history of family members affected with chikungunya few days prior to the mother developing fever. On examination, the child had icterus and hepatosplenomegaly. Systemic examination, including central nervous system and cardiac examination was normal. There were multiple small (0.5-1cm) necrotic ulcers with elevated margins, coalescing in few areas to form larger ulcers present over the extensor and flexor aspect of upper and lower limbs including dorsa of hands, feet and genital region [Figure - 2]a. Multiple skin coloured to yellowish papules and nodules were present on chest along with tiny necrotic ulcers over the umbilical region [Figure - 2]b. Ill-defined hyperpigmented macules were seen on nose and perinasal region. Palms and soles showed multiple necrotic ulcers along with fixed flexion deformity of right hand and right foot. Mucosal examination was unremarkable. Differential diagnosis considered in our case was TORCH infections, neonatal lupus and subcutaneous fat necrosis. Blood investigations were significant for anaemia (10.2 g/dl), leukocytosis (21400/mm[3]), thrombocytopenia (121000/mm[3]) and increased liver enzymes (SGOT: 225 U/L, SGPT: 445 U/L, total bilirubin: 7.9 mg/dl). TORCH profile, antinuclear antibody profile, creatine phosphokinase, serum calcium levels and prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were normal. ELISA for IgM for chikungunya infection in the child and mother was positive. Skin biopsy from one of the ulcers on the thigh showed mild hyperkeratosis along with calcific deposits in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue suggestive of dystrophic calcification [Figure - 3]a and [Figure - 3]b. Infantogram showed multiple calcific deposits [Figure - 4]. The child showed good improvement with supportive measures and physiotherapy. Child was regularly followed till 2 years of age and all the skin lesions healed with atrophic scars and no deformities [Figure - 5].

|

| Figure 1: Ill-defined hyperpigmented macules on the face and trunk along with exfoliation over the extremities (day 1 of life) |

|

|

|

| Figure 4: Infantogram showing multiple calcific deposits (pointed in red arrows) |

|

| Figure 5: Healed atrophic scars on extremities at 2 years of age |

Chikungunya infection was considered as non-lethal disease but recently there is excess mortality documented in different parts of the world including India.[1],[2],[3] Vertical transmission rate varies from 27.2% to 48.29%.[3] The largest outbreak of mother to child transmission of chikungunya was reported in 2005-2006 on the Reunion Island, France.[4] Most of the newborns (88%) are asymptomatic when maternal infection occurs at end of gestation, and only 12% are symptomatic with severe symptoms like respiratory distress, sepsis, intravascular coagulation, meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, pericarditis and intracerebral haemorrhage leading to persistent disabilities. Maternal infection less than 22 weeks of gestation can result in preterm birth, still birth, miscarriages and fetal death.[5] Viral genome has been found in amniotic fluid, placenta and brain of foetus. Till date no congenital malformation has been reported. The exact pathomechanism underlying vertical transmission is not known as human syncytiotrophoblast is non-permissive to Chikungunya virus. Direct inoculation of virus into blood, high maternal viral load and viral tropism to specific organ and neonatal host factors may contribute to severity of the disease.[5],[6] Specific viral lineage and genetic motifs are associated with certain clinical features in different geographical region.

Hyperpigmentation and vesiculobullous lesions are well documented in neonates and young children. Characteristic freckle like pigmentation on nose ('chik' sign) gives a clue to the diagnosis of chikungunya infection retrospectively.[1] In our case, the mother was infected at the end of the 8th month of pregnancy. Child would have been infected in utero during the same period. The possible mechanisms include direct inoculation of virus into blood or through subclinical placental abruption skipping the incubation period.[5]

Child had hyperpigmented macules along with calcinosis at birth, which points that the skin lesions would have occurred in utero only. IgM antibodies to chikungunya virus can be detected 3-5 days after the infection and remain positive for several weeks to 3 months.[7]

This case is presented to highlight the unique skin feature of extensive dystrophic calcification associated with congenital chikungunya infection. The child responded well with just supportive therapy, and skin lesions resolved with almost no sequelae.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient's parents have given their consent for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient's parents understand that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Inamdar AC, Palit A, Sampagavi W, Raghunath S, Deshmukh NS. Cutaneous manifestation of chikungunya fever: observation made during a recent outbreak in South India. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:154-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Mavalankar D, Shastri P, Bandyopadhyay T, Parmar J, Ramani KV. Increased mortality rate associated with chikungunya epidemic, Ahmedabad, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:412-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Oliveira RM, Barreto FK, Maia AM, Gomes IP, Simião AR, Barbosa RB, et al. Maternal and infant death after probable vertical transmission of chikungunya virus in Brazil – Case report. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:333.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Fritel X, Rollot O, Gerardin P, Gauzere BA, Bideault J, Lagarde L, et al. Chikungunya virus infection during pregnancy, Reunion, France, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:418-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Torres JR, Falleiros-Arlant LH, Dueñas L, Pleitez-Navarrete J, Salgado DM, Castillo JB. Congenital and perinatal complications of chikungunya fever: A Latin American experience. Int J Infect Dis 2016;51:85-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Gérardin P, Sampériz S, Ramful D, Boumahni B, Bintner M, Alessandri JL, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of children exposed to perinatal mother-to-child Chikungunya virus infection: The CHIMERE cohort study on Reunion Island. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e2996.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Vasani R, Kanhere S, Chaudhari K, Phadke V, Mukherjee P, Gupta S, et al. Congenital chikungunya – A cause of neonatal hyperpigmentation. Pediatr Dermatol 2016;33:209-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,878

PDF downloads

1,420