Translate this page into:

Controlled trial comparing the efficacy of 88% phenol versus 10% sodium hydroxide for chemical matricectomy in the management of ingrown toenail

2 Department of Community Medicine, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Chander Grover

420-B, Pocket 2, Mayur Vihar, Phase-1, Delhi - 110 091

India

| How to cite this article: Grover C, Khurana A, Bhattacharya SN, Sharma A. Controlled trial comparing the efficacy of 88% phenol versus 10% sodium hydroxide for chemical matricectomy in the management of ingrown toenail. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015;81:472-477 |

Abstract

Background: Partial nail avulsion with lateral chemical matricectomy is the treatment of choice for ingrown toenails. Phenol (88%) is the most widely used chemical agent but prolonged postoperative drainage and collateral damage are common. Sodiumhydroxide (NaOH) 10% has fewer side-effects. Methods: Adult, consenting patients with ingrown toenails were alternately allocated into two treatment groups in the order of their joining the study, to receive either 88% phenol (Group 1, n = 26) or 10% NaOH (Group 0, n = 23) chemical matricectomy. The patients as well as the statistician were blinded to the agent being used. Post-procedure follow-up evaluated median duration of pain, discharge, and healing along with recurrence, if any, in both the groups. The group wise data was statistically analyzed. Results: Both the groups responded well to treatment with the median duration of postoperative pain being 7.92 days in Group 0 and 16.25 days in Group 1 (P < 0.202). Postoperative discharge continued for a median period of 15.42 days (Group 0) and 18.13 days (Group 1) (P < 0.203). The tissue condition normalized in 7.50 days (Group 0) and 15.63 days (Group 1) (P < 0.007). Limitations: Limited postsurgical follow up of 6 months is a limitation of the study. Conclusion: Chemical matricectomy using NaOH is as efficacious as phenolisation, with the advantage of faster tissue normalization.INTRODUCTION

Ingrown toenail is a common painful nail condition and a significant number of cases require surgical management in the form of lateral partial nail avulsion of the ingrowing edge; [1] however, a simple avulsion is associated with high chances of recurrence. [2] Destruction of the lateral horns of the matrix (lateral matricectomy) is an essential component in the management of ingrown toenail. [3] This may be achieved by surgical, or more commonly, a chemical destruction of the lateral matrix (chemical matricectomy). [2] Phenol (88% solution) is one of the most common agents used successfully for decades; [4],[5] however, even with careful application, it is known to cause prolonged postoperative drainage with delayed recovery. [6],[7] Alternative agents have often been evaluated to lessen the postoperative morbidity. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH; 10% solution) is an alternative, which has been found to be safe and efficacious, with less postoperative drainage; however, long-term efficacy data are lacking. [6],[8]

We conducted a prospective, comparative trial of the long-term efficacy of chemical matricectomy using phenol and NaOH; as well as to compare the healing times and postoperative morbidity associated with the two agents.

METHODS

The trial protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the University College of Medical Sciences and Associated Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi. The study was also registered with Central Trials Registry of India (CTRI) (vide number CTRI/2013/11/004164). Patients, aged between 18 and 60 years, presenting to our dermatology clinic with a clinical diagnosis of an ingrown toenail were included. Patients with significant peripheral arterial disease, known allergy to agents being used, severe systemic disease, or conditions associated with delayed wound healing (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes mellitus) were excluded from the study.

Informed, written consent of all participants was taken prior to enrolment. The affected toe and foot were evaluated at baseline for the stage and type of ingrown toenail and the condition of the nail structures using the following criteria: Stage 1 was defined as the presence of only mild erythema or edema, with pain on applying pressure, Stage 2 as significant erythema or edema with sero-purulent drainage from the affected nail fold and Stage 3 as significant drainage, formation of granulation and lateral wall hypertrophy. [6] At baseline, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of the nail clipping was examined to rule out fungal infection for all patients with nail thickening, distal onycholysis, or subungual debris. Only mycologically negative cases were included in the study.

All included patients were asked to grade their pain on a visual analog scale (VAS) of 0 to 10 (0 being no pain and 10 being unbearable pain). The patients were then allocated alternately to the two treatment groups in the order in which they joined the study. Group 1 patients were treated with 88% phenol chemical matricectomy while Group 0 patients received 10% NaOH application. The allocation was done by the nursing assistant not otherwise involved in the study. The corresponding solution (phenol or NaOH) was provided to the operator (CG or AK).

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure consisted of digital block to anesthetize the digit, exsanguination and tourniquet application to assist hemostasis followed by partial avulsion of the lateral nail plate to remove the full length of the ingrown nail plate sliver. The lateral tunnel created was then curetted to remove any granulation tissue/crust if present.

Chemical matricectomy was then done with the appropriate agent (as per group allocation). It was provided by the operating assistant onto a cotton tipped applicator, which was vigorously rubbed onto the lateral horn of the nail matrix. The application time used for both the agents was 1 min. [9],[10] Care was taken to prevent contact with surrounding structures as this could cause more extensive damage than intended and delay wound healing. Following this, the excess solution was neutralized.

The operated toe was then dressed with a paraffin gauze and bandage. Patients were instructed to rest the foot for the rest of the day and keep it in an elevated position. Analgesics were advised to be taken only when required and patients were asked to record their use. No routine postoperative antibiotics were given. Patients were followed up every 2 days for the first 2 weeks and then weekly till complete healing was achieved. For the first 2 weeks, the area was cleaned and the dressing was changed by the investigators. Subsequently, patients were instructed to dress the part, if drainage continued. A photographic record of each visit was maintained. Once the patient became symptom free, monthly follow up visits were advised for the next 6 months, or longer, to assess for recurrence.

At each visit, we recorded the pain as perceived by the patient on a visual analogue acale (VAS) of 0-10, amount of wound drainage (on a scale of 0-4, as detailed) and tissue damage. Drainage was graded as grade 0: no discharge, grade 1: minimal soakage of dressing with no visible discharge, grade 2: mild discharge on pressing the folds only, grade 3: discharge visible on the toe, and grade 4: excessive discharge. Bacterial cultures from the nail bed were sent on the 5 th and 8 th day following surgery and any infection, if present, was appropriately treated.

Statistical analysis

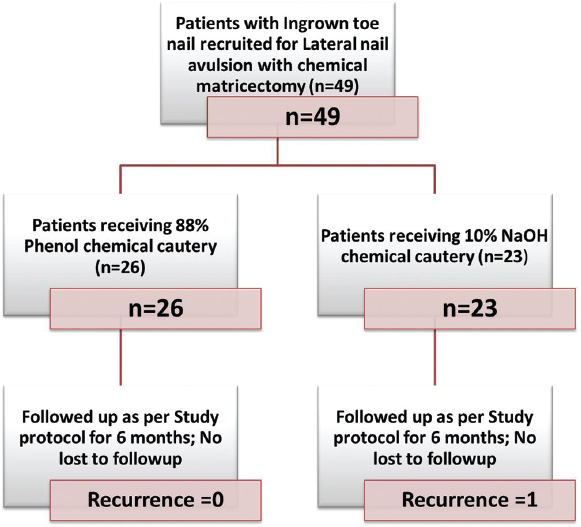

The study flow is outlined in [Figure - 1]. SPSS version 20.0 was used to analyze the data. A comparative analysis of the median duration estimates in both the groups was done using Wilcoxon signed rank test. A survival analysis was carried out at the end to detect difference in survival time for the three variables with respect to the two groups of patients. Each outcome was considered as a failure event and the median time for each event was calculated. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare time to event outcome between groups.

|

| Figure 1: Study flowchart |

Sample size estimation

Based on the previous studies, patients treated with 88% phenol for 1 min require 17.2 days to heal and those with 10% NaOH require 9.2 days to heal. [6] Hence, to determine the amount of difference between the times to healing, with an a priori alpha error of 5%; beta error of 20%; and power of study being 80%, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 16 patients in each group. Assuming an attrition rate of 25%, at least 20 patients were planned to be recruited in each group.

RESULTS

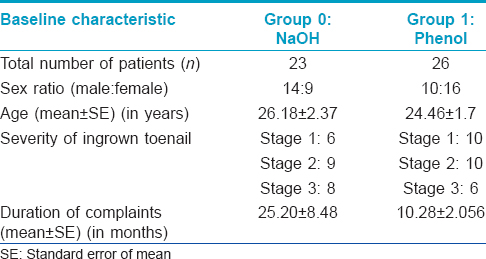

A total of 49 patients were included in the study protocol [Figure - 1]. A baseline assessment of the two treatment groups is shown in [Table - 1]. It can be seen that both the groups were comparable with respect to their demographic characteristics and disease severity.

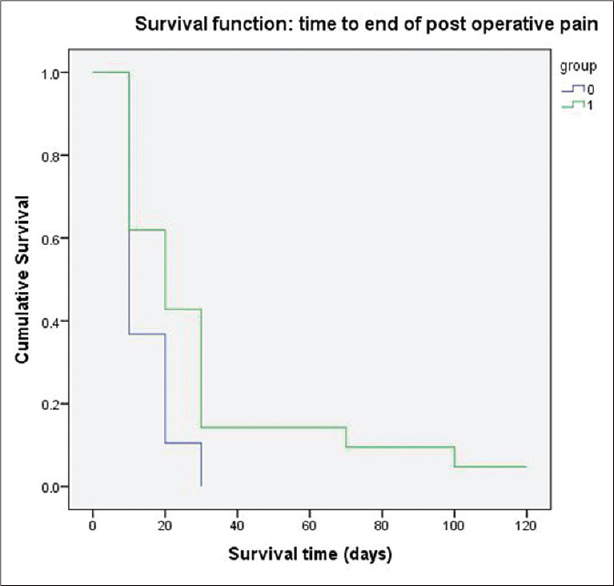

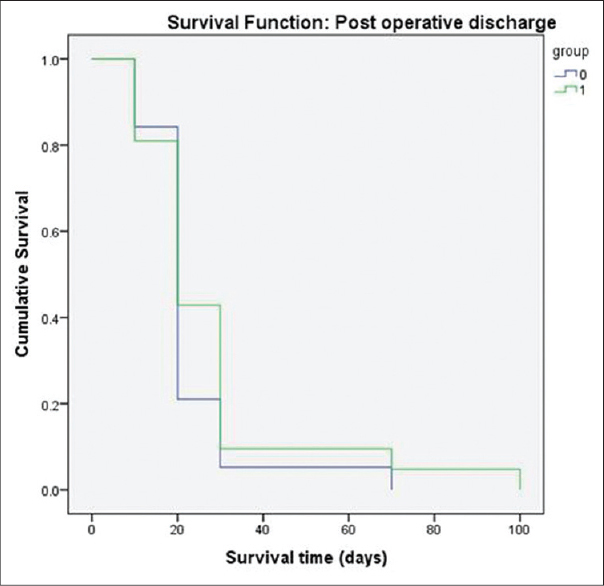

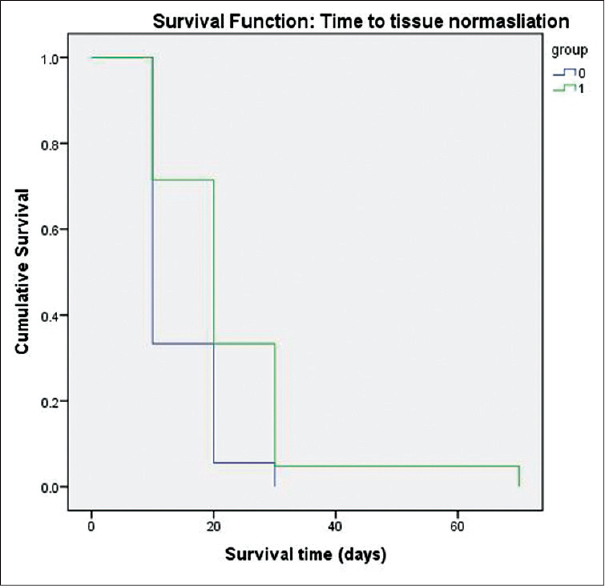

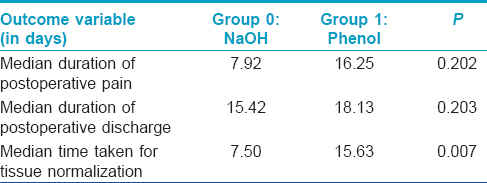

The intended outcome measures for the two groups are compared in [Table - 2]. On comparing the two groups using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, pain lasted 7.92 days in the sodium hydroxide group and 16.25 days in the phenol group, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.202). Discharge from the surgical wound lasted for a median duration of 15.42 days in the sodium hydroxide group and 18.13 days in the phenol group. This difference was also not statistically significant (P = 0.203). The tissue condition took 7.50 days to normalize in the the sodium hydroxide group, while it took 15.63 days to normalize in the phenol group. This difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.007). [Figure - 2], [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4] show the survival curves for all the three outcome variables.

|

| Figure 2: Survival curves with respect to postoperative pain recorded in the two treatment groups (Group 0 treated with 10% sodium hydroxide; Group 1 treated with 88% phenol) |

|

| Figure 3: Survival curves with respect to postoperative discharge duration recorded in the two treatment groups (Group 0 treated with 10% sodium hydroxide; Group 1 treated with 88% phenol) |

|

| Figure 4: Survival curves with respect to tissue normalization recorded in the two treatment groups (Group 0 treated with 10% sodium hydroxide; Group 1 treated with 88% phenol) |

Treatment was successful in all the treated patients of both the groups with resolution of all symptoms caused by the ingrown nails as noted in serial clinical photographs of patients from both groups [Figure - 5] and [Figure - 6]. Three patients each in both groups were found to have secondary infection with bacteriological cultures showing Staphylococcus aureus. All the six patients responded to standard courses of anti-staphylococcal antibiotics. One patient in the sodium hydroxide group developed a recurrence of the condition in the follow up period and was treated with phenol the second time. No other side effects were recorded in any of the treatment groups.

|

| Figure 5: Group 0 (sodium hydroxide treated): Right lateral ingrown toenail at baseline. Subsequently at Week 2, there is significant healing and no apparent discharge. At the completion of 6-month follow up period, the nail unit is healthy with no evidence of recurrence |

|

| Figure 6: Group 1 (Phenol treated): Right lateral ingrown toenail at baseline. Subsequently at week 2, there is significant tissue resolution but minimal persistent tissue necrosis. At the completion of 6 months follow up, the nail unit is healthy with noticeable hyperpigmentation in this patient |

DISCUSSION

Ingrown toenail is one of the most common painful nail conditions presenting to a dermatologist. It is a result of the lateral edge of the nail plate getting embedded in the nail fold (where it acts as a foreign body) resulting in a cascade of inflammation, infection and the reparative process. [1],[6] The condition most commonly involves the great toes and mainly affects young adults, [11] as was seen in our study, where the average age was 25.8 and 24.9 years in both the groups. This may be related to increased chances of sustaining minor trauma to the feet owing to an active lifestyle. Rarely, elderly individuals or infants may be affected.

Surgical management is the mainstay of treatment as conservative methods have a low rate of success in the long run. [2] The standard surgical approach for the management of an ingrown toenail is avulsion of the nail plate with destruction of the underlying matrix. [1],[12] The matrix destruction should be selective to minimize damage to the surrounding normal structures, but at the same time it must be complete and reliable to prevent recurrences. [13]

Selective matricectomy can be performed using surgical or chemical methods. Chemical matricectomy uses various chemical agents to destroy the lateral nail matrix. Among these, phenol is the most common agent used in most clinics. It is an effective protein denaturant which shows its cauterizing effect by producing a coagulation necrosis in the matrix and the surrounding soft tissue. [14],[15],[16] It has been widely studied and is reported to be more effective at preventing symptomatic recurrences (recurrence rates ranging from 1% to 9.6%) as compared to nail avulsion alone (42-83%). [2],[17] However, due to the prolonged healing time of necrosed tissue, it carries an increased risk of postoperative infection. [2] The post-operative discharge generally lasts for about 2-4 weeks but may continue for up to 6 weeks. [6] In addition, phenol is contraindicated in those with moderate or severe vascular disease of the foot, conditions predisposing to delayed wound healing, allergy to the chemical and in pregnancy. [18],[19] We used an application time of 1 min for phenol based on the study by Tatlican et al., which showed that 1 min is sufficient for causing matrix damage while longer durations of application may result in post-procedure discharge persisting for longer periods. [10] However, a recent study has suggested that a more prolonged application time of up to 4 min is needed for effective matricectomy. [20]

Sodium hydroxide is a strong basic salt that, in contrast to phenol, causes basic tissue destruction and produces a liquefaction necrosis that is known to heal more rapidly than the coagulation necrosis produced by phenol. [21] It has been shown to have an efficacy similar to phenol, but with a shorter recovery time. [6] A solution of sodium hydroxide, 10% applied for up to 3 min has been reported to be effective in producing chemical matricectomy with application times of 3 s to 3 min having been used in different studies. [8] The destructive action of sodium hydroxide can be stopped by lavage with 10% acetic acid. Kocyigit et al. compared three different application times and suggested that 1 min application is simple, safe and effective for the treatment of ingrown toenail. [8] The average duration of pain following sodium hydroxide matricectomy has been shown to be between 0.5 and 1 week, while wound drainage lasts for about 1-2 weeks. [8] Recurrence rates are reported to be between 0% and 5%. [8],[21]

Other methods used are surgical matricectomy and ablative methods such as carbon dioxide laser, [8],[22] electrocautery and radiofrequency. [12] The latter techniques are more technically demanding and more expensive compared with chemical matricectomy, and hence not used as commonly.

Previous studies have compared sodium hydroxide and phenol but had differing results. [3],[6] In a series of small controlled prospective studies, Gem et al. found that similar results were obtained using either 80% phenol or 10% NaOH. [3] Bostanci et al. studied 46 patients with 154 ingrown nail sides and noted a longer duration of post-procedure pain with sodium hydroxide compared to phenol, a difference they attributed to the anesthetic properties of phenol. [6] This is in contrast to our study where the median duration of pain was shorter with sodium hydroxide, probably because we used a 1 min application time for both agents as compared with a 3 min application time of phenol used by Bostanci et al. [6] In the same study, postoperative discharge was reported to last for a median of 10 days in the sodium hydroxide group and 15 days in the phenol group, while the tissue damage to nail folds lasted for a median of 3 days with sodium hydroxide and 10 days with phenol. Values for both of these parameters were higher in our study, possibly because of the higher risk of secondary infection in tropical climates; as illustrated by the development of secondary infection with Staphylococcus aureus in six study patients. However, the faster recovery of tissue damage with sodium hydroxide was noted in our study as well. Phenol is a time tested method of chemical matricectomy that has been used for a long period with data regarding the use of sodium hydroxide being sparse and so the latter is not a commonly used agent in most clinics. However, our study shows that it has several advantages over phenol: it has the same degree of efficacy but postoperative discharge occurs for a shorter period allowing a faster return to routine activities for the patient. Lesser tissue destruction could possibly prevent long term scarring and subsequent disfigurement of the nail apparatus.

Limitations

We were unable to ensure operator-blinding in our study as the pungent odor of phenol was difficult to conceal. However, a standard application time and technique was enforced to counteract this limitation to some extent. Another limitation was the short follow up period of 6 months as we could not detect late recurrences that may, in a few cases, manifest 18-24 months after the procedure.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that 10% sodium hydroxide is as efficacious as 88% phenol as a means of chemical matricectomy in the management of ingrown toenail. It offers a slightly better adverse effect profile.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Eekhof JA, Van Wijk B, Knuistingh Neven A, van der Wouden JC. Interventions for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;4:CD001541.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Rounding C, Bloomfield S. Surgical treatments for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2:CD001541.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Gem MA, Sykes PA. Ingrowing toenails: Studies of segmental chemical ablation. Br J Clin Pract 1990;44:562-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Boll OF. Surgical Correction of Ingrowing toenails. J Natl Assoc Chirop 1945;35:8-9

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Byrne DS, Caldwell D. Phenol cauterization for ingrowing toenails: A review of five years′ experience. Br J Surg 1989;76:598-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Bostanci S, Kocyigit P, Gürgey E. Comparison of phenol and sodium hydroxide chemical matricectomies for the treatment of ingrowing toenails. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:680-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Bostanci S, Ekmekçi P, Gürgey E. Chemical matricectomy with phenol for the treatment of ingrowing toenail: A review of the literature and follow-up of 172 treated patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2001;81:181-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Travers GR, Ammon RG. The sodium hydroxide chemical matricectomy procedure. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1980;70:476-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Kocyigit P, Bostanci S, Ozdemir E, Gürgey E. Sodium hydroxide chemical matricectomy for the treatment of ingrown toenails: Comparison of three different application periods. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:744-7; discussion 747.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, Eskioğlu F, Adiyaman S. Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: An efficacy and safety study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2009;43:298-302.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Freiberg A, Dougherty S. A review of management of ingrown toenails and onychogryphosis. Can Fam Physician 1988;34:2675-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Heidelbaugh JJ, Lee H. Management of the ingrown toenail. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:303-8

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Yang KC, Li YT. Treatment of recurrent ingrown great toenail associated with granulation tissue by partial nail avulsion followed by matricectomy with a Sharpulse carbon dioxide laser. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:419-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Espensen EH, Nixon BP, Armstrong DG. Chemical matricectomy for ingrown toenails: Is there an evidence basis to guide therapy? J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92:287-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Baran R, Haneke E. Matricectomy and nail ablation. Hand Clin 2002;18:693-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Siegle RJ, Stewart R. Recalcitrant ingrowing nails: Surgical approaches. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1992;18:744-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Chiacchio ND, Belda W Jr, Chiacchio NG, Kezam Gabriel FV, de Farias DC. Nail matrix phenolization for treatment of ingrowing nail: Technique report and recurrence rate of 267 surgeries. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:534-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Sykes PA, Kerr R. Treatment of ingrowing nails. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1988;335-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Siegle RJ, Harkness J, Swanson NA. Phenol alcohol technique for permanent matricectomy. Arch Dermatol 1984;120:348-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Viejo Tirado F, Serrano Pardo R. Cauterization of the germinal nail matrix using phenol applications of differing durations: A histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:706-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Ozdemir E, Bostanci S, Ekmekci P, Gurgey E. Chemical matricectomy with 10% sodium hydroxide for the treatment of ingrowing toenails. Dermatol Surg 2004;30:26-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Ozawa T, Nose K, Harada T, Muraoka M, Ishii M. Partial matricectomy with a CO2 laser for ingrown toenail after nail matrix staining. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:302-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

13,802

PDF downloads

2,916