Translate this page into:

Cryptic exposure to arsenic

Correspondence Address:

Robert A Schwartz

Dermatology, New Jersey Medical School, 185 South Orange Avenue, Newark, New Jersey 07103-2714

USA

| How to cite this article: Rossy KM, Janusz CA, Schwartz RA. Cryptic exposure to arsenic. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:230-235 |

Abstract

Arsenic is an odorless, colorless and tasteless element long linked with effects on the skin and viscera. Exposure to it may be cryptic. Although human intake can occur from four forms, elemental, inorganic (trivalent and pentavalent arsenic) and organic arsenic, the trivalent inorganic arsenicals constitute the major human hazard. Arsenic usually reaches the skin from occupational, therapeutic, or environmental exposure, although it still may be employed as a poison. Occupations involving new technologies are not exempt from arsenic exposure. Its acute and chronic effects are noteworthy. Treatment options exist for arsenic-induced pathology, but prevention of toxicity remains the main focus. Vitamin and mineral supplementation may play a role in the treatment of arsenic toxicity.

INTRODUCTION

Arsenic is a naturally occurring ubiquitous element. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5] It is an odorless, colorless, nearly tasteless element present in elemental, organic, and inorganic (trivalent and pentavalent) forms.[2],[5],[6],[7] The inorganic forms are more common sources of toxic exposure to arsenic, causing both acute and chronic effects on man, while the organic forms are generally thought to be much less toxic.[1],[6],[8],[9] The trivalent inorganic form of arsenic, arsenite [As (III)], and the pentavalent form, arsenate [As (V)], are both contaminants of groundwater and foods, but arsenite is the more toxic of the two.[7],[8],[10] The mechanism of toxicity is uncertain, but generation of free radicals or interference in the glutathione pathway causing oxidative stress has been hypothesized.[7] Trivalent arsenic, in the form of Fowler′s solution (KAsO2), Asiatic pills (As2O3), and Donovan′s solution (AsI3), has also been used for medicinal purposes. Although pentavalent forms of arsenic are not components of medical therapies, they are common in contaminated sources in nature. On ingestion, they are reduced to the trivalent form. Organic forms of arsenic are the predominant type identified in seafood.[1],[11],[12]

There are theories about the mechanisms in which arsenic is carcinogenic to humans, but there is limited proof to support them due to the lack of animal models. Animal research on the carcinogenicity of arsenic is not useful because arsenic does not induce cancer in these models.[10] In vivo cytogenetic assays of lymphocytes of humans exposed to arsenic show high levels of chromatid breaks, deletions and, to a lesser degree, chromosomal exchange. These correlations suggest that arsenic induces chromosomal aberrations in a dose-dependent manner.[10]

In nature, arsenic is frequently found in combination with other elements like sulfur, oxygen, and iron. The most common existing forms are orpiment (As2S3), realgar (AsS), arsenopyrite (FeAsS), arsenolite (As2O3) and lollingite (FeA+S2). These arsenic compounds commonly occur in gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, cobalt, and tin ores.[8] Smelting of these compounds can release large quantities of arsenic into the environment, causing unrecognized contamination of the surrounding air, water, soil, and vegetation.[10]

For millions of people around the world, the source of chronic arsenic toxicity is usually cryptic, due to unknown environmental, occupational, or medicinal exposure.[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18] Over the past 20 years there has been increased interest in arsenicism, resulting from increased awareness of toxic levels of arsenic in water and food supplies. India, Bangladesh, China, Argentina, Mexico, Pakistan, and Chile are the countries most affected by chronic exposure to arsenic via contaminated water supply.[9],[10] After toxic levels of arsenic were identified in the 1980s, efforts have been made to clean the water supply in West Bengal, India and Bangladesh. Presently, concern is rising in neighboring areas such as the Gangetic Plains, Terai of Nepal, Padma-Meghna-Brahmaputra delta, Chandigarh region, and Bihar.[7],[19] Efforts have been initiated to rectify this problem, but many of these countries lack the funds to support these efforts.[1]

ENVIRONMENTAL AND MEDICINAL EXPOSURE

Groundwater contamination with arsenic is a worldwide concern. The World Health Organization has identified many regions with groundwater levels of arsenic that greatly exceed the limit of 50 micrograms per liter.[1],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[20],[21] As many as 42 million people in 9 out of 18 districts in West Bengal, India are exposed to high arsenic levels in their water supply.[22] For their groundwater supply, these people rely on tube wells. This water is used for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. These tube wells contain water contaminated with high levels of arsenic (there are some reports of arsenic levels as high as 3 milligrams per liter).[7],[21] It has been proposed that withdrawal of groundwater via tube wells results in oxidative and reductive reactions causing the decomposition of iron pyrites and release of arsenic.[11]-[12] In this region, rivers are being contaminated with arsenic as a result of redistribution of groundwater during the monsoon.[19]

In West Bengal and Bangladesh, tube wells also supply the water used for irrigation.[1],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[21],[23] With the increase in population over the years in India and Bangladesh, irrigation-dependent agricultural systems have become necessary. As a result, high levels of arsenic have been reported in products that are considered staples, such as vegetables, rice, and herbs.[12],[21],[22],[23] Vegetables have high levels of arsenic absorbed in their skins, with lower levels found in the fleshy inner portions.[12],[21] Higher levels of arsenic are found in cooked items than in raw ones because of the use of contaminated water to rinse and cook vegetables.[21]

Arsenic present in food composites is a matter of concern for both humans and animals. Arsenic-contaminated groundwater is often used in Bangladesh and West Bengal to irrigate crops used for food and animal consumption and high concentrations of arsenic have been reported in the rice crops in these areas. Both humans and cattle feed on rice crops, and high levels of arsenic are found in both groups.[24] Arsenic could enter the human food chain wherever this food is consumed, including countries as distant as the United Kingdom.[23] In Canada, USA, and Japan, the highest levels of organic arsenic are in seafood.[6],[12],[21] High concentrations of arsenic have also been noted in "moonshine", an illegally produced potent alcoholic beverage.[25]

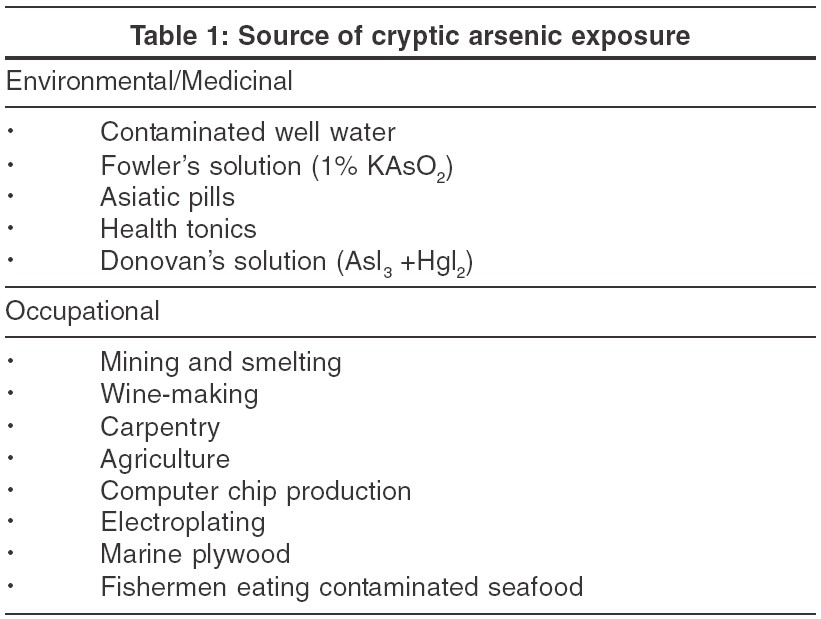

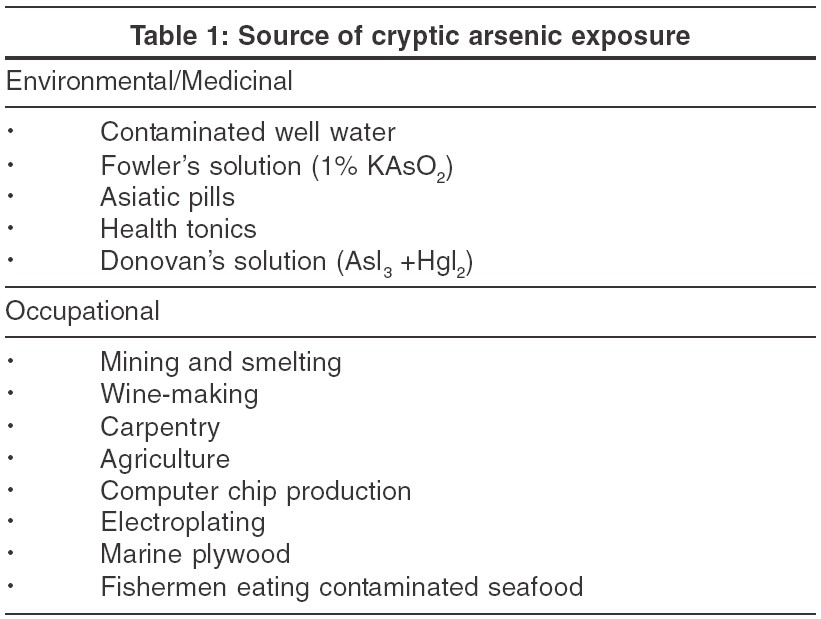

Medicinal exposure to arsenic has been significant since the past few centuries [Table - 1]. Arsenic was first introduced into the US Pharmacopoeia in 1850, with the use of arsenous iodide and a solution of arsenous and mercuric iodide.[25] In Europe and the USA, arsenic compounds, such as Fowler′s solution and Asiatic pills, were used as medications until 1965 to treat leukemia, psoriasis, asthma, pemphigus, pernicious anemia, and Hodgkin′s disease.[26], [27] Today, arsenic use continues with medications such as arsenic trioxide (Trisenox), used for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia.[8],[27],[28] Cases have been reported from China and Singapore of chronic arsenic poisoning from anti-asthmatic herbal preparations that contain inorganic arsenic sulfide, and from other medicinal tonics.[29] Arsenic has been used with opium in India as an aphrodisiac and in herbal remedies for various illnesses.[30],[31] Asian immigrants have been reported to import powdered blends of folk remedies that are high in arsenic sulfide.[32] Chronic arsenic toxicity can also result from intentional poisoning over an extended period of time.

Another subtle cause of arsenic poisoning is the burning of chromium copper arsenate (CCA) treated wood.[9],[33] There have been suggestions of a link between the use of CCA-treated wood to build decks and playgrounds and possible arsenic toxicity. There is concern about children′s exposure to the arsenic that leaches from these structures.[34] A recent soil analysis study indicated that arsenic does not migrate laterally but accumulates under elevated platforms at levels that can exceed the soil guideline. Chronic arsenic exposure may increase the risk of fetal and infant death.[35] CCA-treated wood is banned in Europe, Asia, and the USA.[36],[37] There is increased research to determine the appropriate method to dispose wood high in arsenic and chromium in landfills, and to identify safe and effective alternatives for playgrounds and decks.[36],[37]

In Taiwan, a significant dose-response trend in lung cancer risk was identified in those who had ingested arsenic, and this was more prominent in cigarette smokers.[38]

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

In 1973 it was reported that over 1.5 million workers in America alone in various occupations were being exposed to inorganic forms of arsenic, either directly or via contaminated water or soil.[16] Mining is one activity with an increased risk of arsenic exposure, since arsenic is an element that coexists with gold, cobalt, zinc, lead, and coal. There is also an increased risk of arsenic toxicity with smelting of non-ferrous metal ores, which produces an arsenic byproduct.[4] Smelter workers in Sweden have been found to have higher levels of arsenic in their bodies when compared to control subjects.[10] Abrasive blasting operations, both indoors and outdoors, with copper slag abrasive contribute to arsenic exposure and possible toxicity.[39]

In America arsenic has played a big role in agricultural practice, and has been used in pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, desiccants, and feed additives.[40] Worldwide, arsenic continues to be used in pesticides and fungicides to treat small gardens. Cases of chronic arsenicism have been reported in Germany in areas where such pesticides were used on vineyards.[2],[41]

With advances in technology, new opportunities for arsenic use and exposure have arisen. For example, computer microchips have improved in speed by using gallium arsenide in place of silicon substrates.[42] Arsenic and other toxic elements are commonly used in the optoelectric industry, and high levels of arsenic, exceeding the safety range, have been measured in workers′ blood and urine.[43] Arsine and gallium arsenide are both commonly used in the microelectronics industry. Highly insoluble arsenide semiconductors are less toxic acutely when compared to arsine and other more soluble forms, but gallium arsenide causes more lung damage than other compounds.[44] Advances in technology have been accompanied by an increased risk of arsenic exposure for workers. The risk of arsenic toxicity can be effectively minimized by worker education and implementation of safety precautions.[43]

Another unusual cryptic occupational exposure may occur in an emergency room setting.[45] In a suicide attempt a patient may ingest arsenic trioxide. Gastric lavage may then be employed, but most of the poison may remain in the stomach. A total gastrectomy may then be performed, exposing medical staff members to fumes from the patient′s stomach. This may lead to the development of corneal erosion or laryngitis because arsenic trioxide reacts with stomach acid to produce arsine.[45] Protective measures to safeguard medical staff from exposure to arsine gas during the treatment of patients poisoned from ingested arsenic trioxide are desirable.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Arsenicism is a systemic disease that mainly affects the skin, nervous system, gastrointestinal system, and blood.[2],[9],[17],[18],[29] Acute arsenic toxicity can cause gastrointestinal discomfort, with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Death is a potential result. Edema a rsenicalis can be present, with swelling of the face and eyelids. An asymmetric peripheral neuropathy can occur, resembling the Guillain-Barrι syndrome.[9],[46] Mees′ lines, white transverse bands that usually affect all fingernails, can be identified after 2 months of arsenic exposure, allowing for identification of exposure.[9],[17],[47] Brown discoloration of the nails can also occur.[47]

Common dermatological manifestations of chronic arsenic toxicity are diffuse or spotted melanosis, palmar and plantar keratoses, and leukomelanosis.[9],[17],[47],[48] Chronic exposure to arsenic can cause alteration of skin pigmentation and keratoses that can potentially progress to Bowen′s disease or squamous cell or basal cell carcinomas.[10],[17],[18],[20],[48] Hematological disruption may result, with possible anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Peripheral vascular disease (black foot disease), cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and reproductive difficulties can all result from chronic arsenic exposure.[1],[9],[48] Cases of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma and angiosarcoma of the liver have been reported.[9],[48]

Lung, bladder, and kidney malignancies have also been reported in chronic arsenicism.[48] A study in Finland showed a link between chronic low exposure levels of arsenic and the occurrence of bladder cancer.[49] Evidence from this study also suggested a synergistic effect of arsenic and cigarette use on the development of bladder cancer.[49] A study in Taiwan found a dose-response relationship between chronic arsenic exposure through well water and an increased incidence of lung and bladder cancer.[50] Another study that confirmed a relationship between arsenic ingestion and occurrence of liver, bladder, and lung cancer, also noted a higher incidence of lung cancer among copper smelter workers.[51] Myelogenous leukemia may also occur due to chronic toxic exposure to arsenic, "although paradoxically" at lower levels arsenic trioxide is used to treat acute myeloid leukemia.[9],[27]

TREATMENT

Chelating agents, such as dimercaprol, dimercaptosuccinic acid, and dimercaptopanesulfonic acid, can remove arsenic but are only effective while traces of arsenic remain in the body.[9],[52] Chronic cutaneous arsenicism and arsenic-induced basal cell carcinomas can be treated with oral retinoid therapy.[53] The main localized treatment options that are effective for arsenical keratoses are excisional surgery, cryosurgery, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical chemotherapy.[17],[54],[55]

PREVENTION

Prevention of arsenic toxicity through reducing environmental and occupational exposure is key. Efforts need to be continued to ensure that levels of arsenic in water sources are tested and maintained within the acceptable range. Safety precautions when working in occupations with potential exposure should be enforced. CCA-treated wood should not be burned and should not be used. Good nutrition may also play a role in preventing and treating arsenic toxicity.[1],[7],[9],[11],[12],[21] Levels of selenium and zinc are low in those suffering from the effects of chronic arsenic exposure, suggesting a role for selenium and zinc supplementation.[7],[11],[12] Correlations have been made between increased levels of vitamin C and methionine and lower arsenic toxicity, increased sensitivity to arsenic with vitamin A deficiency, and increased toxic effects with diets high in carbohydrates or fats.[21]

Chronic arsenicism represents an important cutaneous sign of internal cancer. Since exposure to arsenic is often cryptic, clinical traces of arsenic are often long gone and the carcinogenic lag may be up to 50 years, it is important to have an elevated index of suspicion for diagnosis of arsenicism in appropriate clinical and environmental settings.

| 1. |

Brown KG, Ross GL. American Council on Science and Health. Arsenic, drinking water, and health: a position paper of the American Council on Science and Health. Regulatory Toxicology Pharmacology 2002;36:162-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Neubauer O. Arsenical cancer: A review. Br J Cancer 1947;1:192-251.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Carlson-Lynch H, Beck BD, Boardman PD. Arsenic risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 1995;102:354-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Fishbein L. Sources, transport and alterations of metal compounds: an overview. 1. Arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, and nickel. Environ Health Perspect 1981;40:43-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Jackson R, Grainge JW. Arsenic and cancer. Canad Med Assoc J 1975;113:396-401.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Bennett BG. Exposure of man to environmental arsenic- an exposure commitment assessment. Sci Total Environ 1981;20:99-107.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Spallholz JE, Mallory Boylan L, Rhaman MM. Environmental hypothesis: is poor dietary selenium intake an underlying factor for arsenicosis and cancer in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India? Sci Total Environ 2004;323:21-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Joshi H, Ghosh AK, Singhal DC, Kumar S. Arsenic contamination in parts of Yamuna sub-basin, West Bengal. Indian J Environ Health 2003;45:265-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Hall AH. Chronic arsenic poisoning. Toxicology Letters 2002;128:69-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Mahata J, Chaki M, Ghosh P, Das LK, Baidya K, Ray K, et al . Chromosomal aberrations in arsenic-exposed human populations: a review with special reference to a comprehensive study in West Bengal, India. Cytogenetic Genome Research 2004;104:359-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Samanta G, Sharma R, Roychowdhury T, Chakraborti D. Arsenic and other elements in hair, nails, and skin-scales of arsenic victims in West Bengal, India. Sci Total Environ 2004;326:33-47.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Roychowdhury T, Tokunaga H, Ando M. Survey of arsenic and other heavy metals in food composites and drinking water and estimation of dietary intake by the villagers from an arsenic affected area of West Bengal, India. Sci Total Environ 2003;308:15-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sommers SC, McManus RG. Multiple arsenical cancers of skin and internal organs. Cancer 1953;6:347-59.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Voron DA, Tonkens SW. Arsenical keratoses. Cutis 1975;15:703-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Schroeder HA, Balassa JJ. Abnormal trace metals in man: arsenic. J Chronic Dis 1966;19:85-106.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Blejer HP, Wagner W. Inorganic arsenic - ambient level approach to the control of occupational carcinogenic exposures. Ann New York Acad Sci 1976;271:179-86.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Schwartz RA. Arsenic and the skin. Intern J Dermatol 1997;36:241-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Southwick GJ, Schwartz RA. Arsenically-associated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with hypercalcemia. J Surg Oncol 1979;12:115-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Chakraborti D, Mukherjee SC, Pati S, Sengupta MK, Rahman MM, Chowdhury UK, et al. Arsenic groundwater contamination in Middle Ganga Plain, Bihar, India: a future danger? Environ Health Perspect 2004;111:1194-201.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Rahman MM, Mandal BK, Chowdhury TR, Sengupta MK, Chowdhury UK, Lodh D, et al . Arsenic groundwater contamination and sufferings of people in North 24-Parganas, one of the nine arsenic affected districts of West Bengal, India. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng 2003;38:25-59.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Roychowdhury T, Uchino T, Tokunaga H, Ando M. Arsenic and other heavy metals in soils from an arsenic-affected area of West Bengal, India. Chemosphere 2002;49:605-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Allred M, Campolucci S, Falk H, Ganguly NK, Saiyed HN, Shah B. Bilateral environmental and occupational health program with India. Int J Environ Health 2003;206:323-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Al Rmalli SW, Haris PI, Harrington CF, Ayub M. A survey of arsenic in foodstuffs on sale in the United Kingdom and imported from Bangladesh. Sci Total Environ 2005;337:23-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Abedin MJ, Cresser MS, Meharg AA, Feldmann J, Cotter-Howells J. Arsenic accumulation and metabolism in rice. Environ Sci Technol 2002;36:962-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Hughes GS Jr, Davis L. Variegate porphyria and heavy metal poisoning from ingestion of "moonshine." South Med J 1983;76:1027-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Engel RR, Smith AH. Arsenic in drinking water and mortality from vascular disease: an ecological study in Finland. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1223-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Evens AM, Tallman MS, Gartenhaus RB. The potential of arsenic trioxide in the treatment of malignant disease: past, present, and future. Leukemia Research 2004;28:891-900.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Barbery JT, Pezzullo JC, Soignet SL. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3609-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Tay CH, Seah CS. Arsenic poisoning from anti-asthmatic herbal preparations. Med J Austral 1975;2:424-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Datta DV. Arsenic in opium. Lancet 1977;1:484.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Narang AP, Chawla LS, Khurana SB. Levels of arsenic in Indian opium eaters. Drug Alcohol Depend 1987;20:149-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Werner MA, Knobeloch LM, Erbach T, Anderson HA. Use of imported folk remedies and medications in the Wisconsin Hmong community. WMJ 2001;100:32-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Peters HA, Croft WA, Woolson EA. Seasonal arsenic exposure from burning chromium-copper-arsenate-treated wood. JAMA 1984;25l:2393-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Ursitti F, Vanderlinden L, Watson R, Campbell M. Assessing and managing exposure from arsenic in CCA-treated wood play structures. Can J Public Health 2004;95:429-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Milton AH, Smith W, Rahman B, Hasan Z, Kulsum U, Dear K, et al . Chronic arsenic exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Bangladesh. Epidemiology 2005;16:82-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Clausen C. Improving the two-step remediation process for CCA-treated wood: Part I. Evaluating oxalic acid extraction. Waste Management 2004;24:401-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Clausen C. Improving the two-step remediation process for CCA-treated wood: Part II. Evaluating bacterial nutrient sources. Waste Management 2004;24:407-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Chen CL, Hsu LI, Chiou HY, Hsueh YM, Chen SY, Wu MM, et al . Blackfoot Disease Study Group. Ingested arsenic, cigarette smoking, and lung cancer risk: a follow-up study in arseniasis-endemic areas in Taiwan. JAMA 2004;292:2984-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Stephenson D, Spear T, Seymour M, Cashell L. Airborne exposure to heavy metals and total particulate during abrasive blasting using copper slag abrasive. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 2002;17:437-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Park MJ, Currier M. Arsenic exposure in Mississippi: a review of cases. South Med J 1991;84:461-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Grobe JW. Periphere Durchblutungssf φrungen und Akrocyanose bei arsengeschδdigten Moselwinzern. Berufs Dermatosen 1976;24:78-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Edelman P. Environmental and workplace contamination in the semiconductor industry: implications for future health of the workforce and community. Environ Health Perspect 1990;86:291-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Liao YH, Yu HS, Ho CK, Wu MT, Yang CY, Chen JR, et al . Biological monitoring of exposure to aluminum, gallium, indium, arsenic, and antimony in optoelectronic industry workers. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46:931-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Carter DE, Aposhian HV, Gandolfi AJ. The metabolism of inorganic arsenic oxides, gallium arsenide, and arsine: a toxicochemical review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2003;193:309-34.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Kinoshita H, Hirose Y, Tanaka T, Yamazaki Y. Oral arsenic trioxide poisoning and secondary hazard from gastric content. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:625-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Schoolmaster WL, White DR. Arsenic poisoning. South Med J 1980;73:198-208.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Madorsky DD. Arsenic in dermatology. J Assoc Milit Dermatol 1977;3:19-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Centeno JA, Mullick FG, Martinez L, Page NP, Gibb H, Longfellow D, et al . Pathology related to chronic arsenic exposure. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:883-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Kurttio P, Pukkala E, Kahelin H, Auvinen A, Pekkanen J. Arsenic concentrations in well water and the risk of bladder and kidney cancer in Finland. Environ Health Perspect 1999;107:705-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Chiou HY, Hsueh YM, Liaw KF, Horng SF, Chiang MH, Pu YS, et al . Incidence of internal cancers and ingested inorganic arsenic: a seven year follow up study in Taiwan. Cancer Res 1995;55:1296-300.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Chen CJ, Chen CW, Wu MM, Kuo TL. Cancer potential in liver, lung, bladder and kidney due to ingested inorganic arsenic in drinking water. Br J Cancer 1992;66:888-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Heyman A, Pfeiffer JB Jr, Willett RW, Taylor HM. Peripheral neuropathy caused by arsenical intoxication. A study of 41 cases with observations on the effects of BAL (2,3, dimercapto-propanol). New Engl J Med 1956;254:401-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Thianprasit M. Chronic cutaneous arsenicism treated with aromatic retinoid. J Med Assoc Thailand 1984;67:93-100.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Rogozinski T, Geiger JM, Czarnetzki BM, Jablonska S. Acitretin in the treatment and prevention of viral, premalignant and malignant skin lesions. J Dermatol Treat 1989;1:91-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Schwartz RA. Skin Cancer Recognition and Management. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988. p. 11-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,847

PDF downloads

2,730