Translate this page into:

Cutaneous malakoplakia: Interesting case report and review of literature

2 Department of Histopathology, K.E.M. Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Correspondence Address:

Mukta S Tulpule

26, Sahawas Society, Karvenagar, Pune - 411 052, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Tulpule MS, Bharatia PR, Pradhan AM, Tawade YV. Cutaneous malakoplakia: Interesting case report and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:584-586 |

Sir,

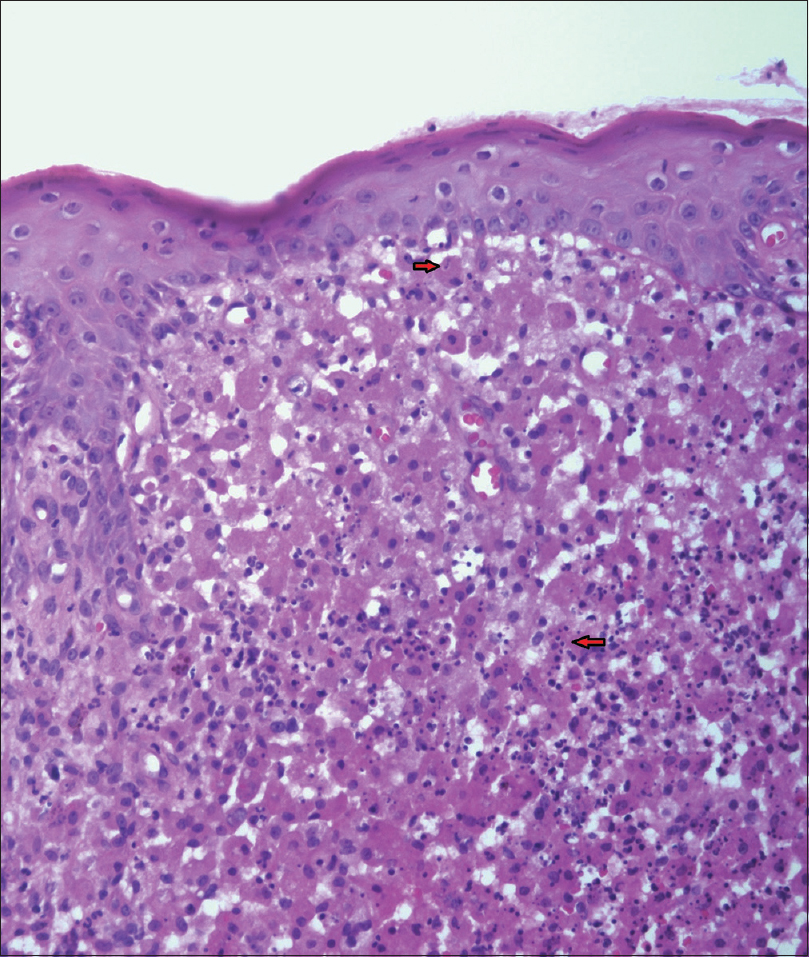

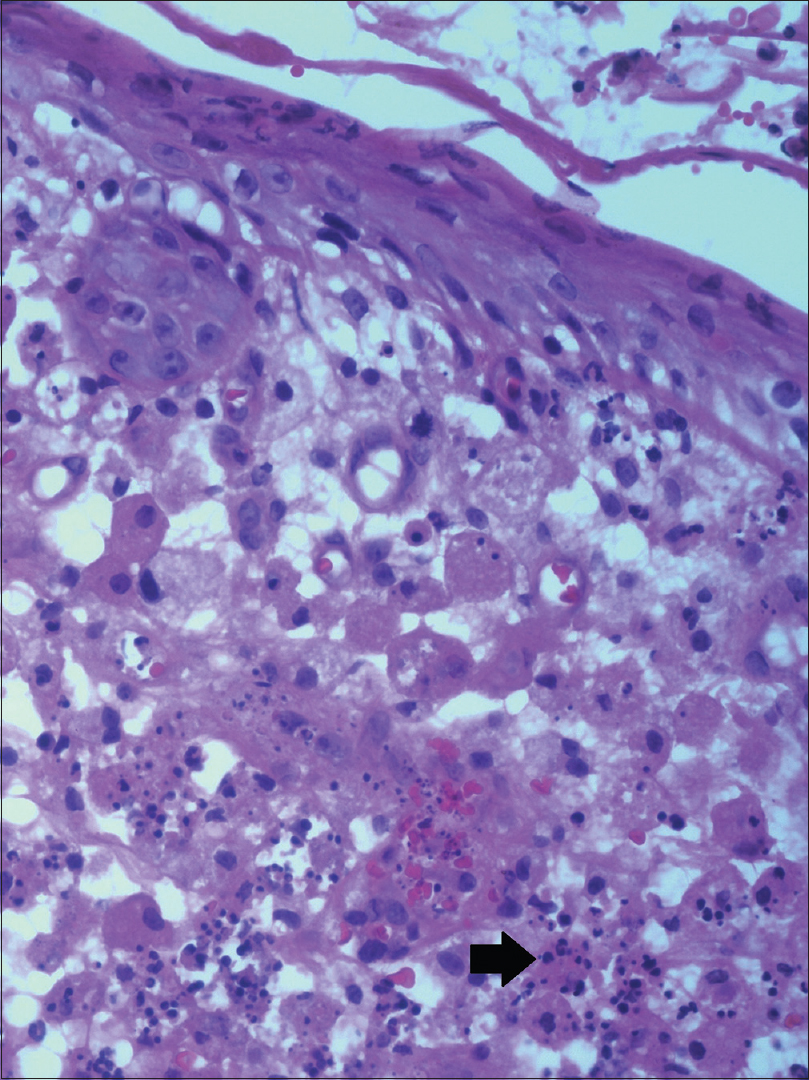

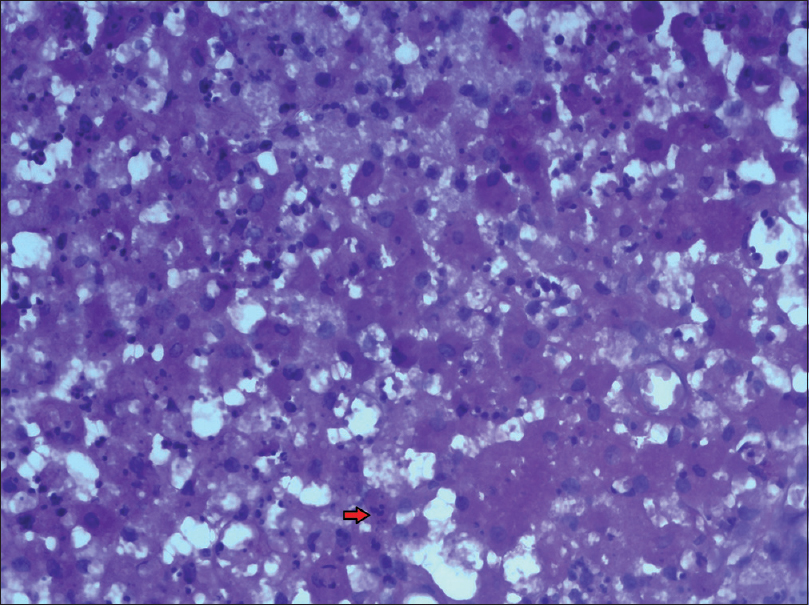

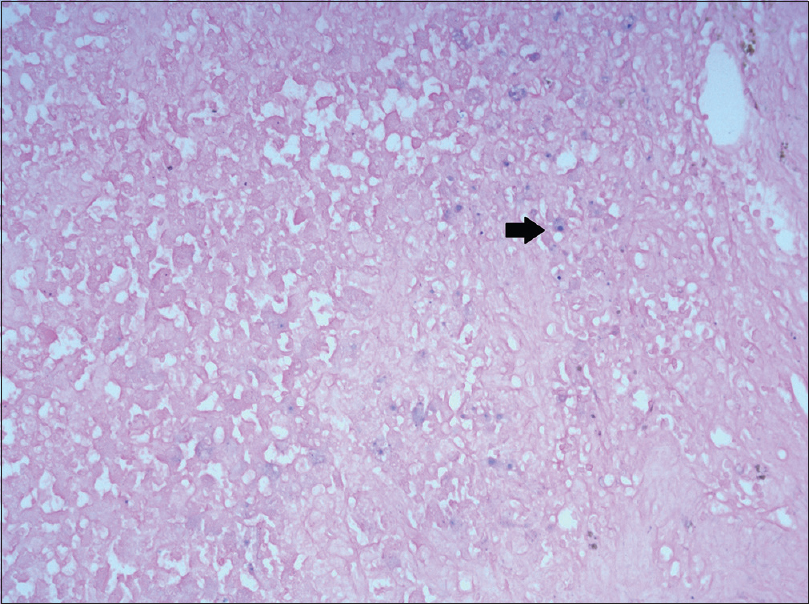

Cutaneous malakoplakia is a rare chronic granulomatous disorder, more frequently presenting in immunocompromised patients. We report a case of a 45-year-old female who presented with painful cutaneous lesions in the genital area for 2 months and fever for 5 days. The patient had undergone a successful kidney transplant 2 years ago for acute tubular necrosis and was on immunosuppressant drugs (azathioprine 100 mg h.s. and prednisolone 20 mg OD) since then. A single, well-defined, indurated, tender, yellow plaque measuring 8 × 3.5 cm, with a granulomatous base and a few bleeding points was present on the surface of the left labia majora [Figure - 1]. Similar smaller nodular lesions were present on the perianal region. A differential diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum, cutaneous Crohn's disease, cutaneous tuberculosis, herpes simplex vegetans, and cutaneous malakoplakia were considered. Routine hemogram revealed low hemoglobin of 10 gm/dl and total white cell count of 14000/cu mm. The lesion was sampled for culture on two occasions, both of which revealed growth of Escherichia coli. Skin biopsy from the lesions showed sheets of macrophages (von Hansemann cells) with round intracytoplasmic, basophilic bodies in the dermis (Michaelis–Guttmann bodies), which were PAS positive [Figure - 2], [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4]. Prussian-blue staining demonstrated deposits of iron within the bodies [Figure - 5]. Von Kossa staining did not demonstrate any calcium deposits within the Michaelis–Guttman bodies, which were not stained on Von Kossa stain. Ziehl–Neelson staining did not reveal any acid-fast organisms. Serology for HIV antibodies I and II, VDRL, and hepatitis B was negative. Fungal culture was negative. Blood and urine cultures were negative. A Mantoux test was performed and was positive with induration of 17 × 15 cm. Chest X-ray was clear. Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis did not reveal any abnormalities. Vaginal colposcopic examination and rectal examination were normal. These tests and skin biopsy ruled out other differentials confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous malakoplakia.

|

| Figure 1: Well-defined plaque with a few bleeding points on left labia majus; a few nodules on the perianal region |

|

| Figure 2: Sheets of macrophages, with round, intracytoplasmic, basophilic inclusion bodies (Michaelis–Guttman bodies) (low-power view – H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 3: High power (H and E, ×400) Michaelis-Guttman bodies |

|

| Figure 4: Periodic acid–Schiff positive intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (high-power view – PAS, ×400) |

|

| Figure 5: Low power view ×10 Prussian blue – deposits of iron within the cells |

A diagnosis of vulval and perianal malakoplakia with no genito urinary extension was made.

The patient was treated with oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 2 months. Although the lesions dried up and the pain reduced, the size did not reduce significantly. Perianal lesions regressed at the end of 2 months. Surgical excision of the lesion on labia majora was considered, but as patient showed improvement with oral medication and was unwilling for further surgical management, it was not done. Revision of doses of immunosuppressants was discussed with the urologist and lowering of steroid dose was considered subsequently.

The term malakoplakia meaning “soft plaque” was first described by von Hansemann in 1901 and Michaelis and Gutmann in 1902.[1] Cutaneous malakoplakia was reported by Leclerc and Bernier in 1972. Malakoplakia is a chronic granulomatous response to infective agents in immunocompromised individuals. The immunocompromised state maybe due to HIV infection, renal transplant, neoplasms, or immunosuppressive medication.[2] The lesions are a result of acquired bactericidal defect of macrophages caused by immunosuppression. Of the 52 cases of cutaneous malakoplakia reported so far, 17 have been in female patients with a male: female ratio of 2:1. The most common site of involvement was perianal 19% (n = 10), and the most common presentation was nodules seen in 23% (n = 12). Other presentations were ulcerations, indurated plaques, and abscesses. There are few case reports of malakoplakia occurring on the abdomen, neck, and face. Only one other case presented on the vulva with ulcerated lesions.[2] According to some reports, in cases of noncutaneous, genitourinary malakoplakia, incidence among females is slightly higher and the age group of sixth to seventh decade is the most commonly affected.[3],[4]

Most common organisms isolated were coliforms such as E. coli, Klebsiella, Proteus in 90% cases; however, Staphylococcus aureus, Rhodococci, Mycobacterium avium, and M. tuberculosis have also been reported.[4]

A defect in the lysosomal killing and digestion of phagocytized bacteria with deficiencies of beta glucuronidase and 3', 5' guanosine monophosphate dehydrogenase has been postulated as the pathology of this condition.[5]

Histopathology is characteristic with presence of large sheets of histiocytes containing basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies called “Michaelis Gutmann bodies.”[6],[7] These bodies have a “target appearance,” are PAS positive, diastase resistant, and stain positive for Von Kossa and Prussian blue due to the presence of calcium and iron.[8]

Management is with wide surgical excision and with antibiotics such as quinolones, with ciprofloxacin being the most effective.[9] Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is also considered useful. Discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment may be considered.[10]

We report this case as a classic and rare example of cutaneous malakoplakia in an immunosuppressed female renal transplant patient, with growth of E. coli and demonstrating “Michaelis–Gutmann” bodies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Michaelis L, Gutman C. About inclusions in bladder tumours Z Klin Med 1902;47:208-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Afonso JP, Ando PN, Padilha MH, Michalany NS, Porro AM. Cutaneous malakoplakia: Case report and review. An Bras Dermatol 2013;88:432-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Long JP Jr., Althausen AF. Malacoplakia: A 25-year experience with a review of the literature. J Urol 1989;141:1328-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ben Amna M, Hajri M, Oumaya C, Anis J, Bacha K, Ben Hassine L, et al. Genito-urinary malacoplakia. Report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Ann Urol (Paris) 2002;36:388-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Mehregan DR, Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA. Cutaneous malakoplakia: A report of two cases with the use of anti-BCG for the detection for micro-organisms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43 (2 Pt 2):351-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Almagro UA, Choi H, Caya JG, Norback DH. Cutaneous malakoplakia. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 1981;3:295-301.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Stanton MJ, Maxted W. Malacoplakia: A study of the literature and current concepts of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. J Urol 1981;125:139-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Rémond B, Dompmartin A, Moreau A, Esnault P, Thomas A, Mandard JC, et al. Cutaneous malacoplakia. Int J Dermatol 1994;33:538-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Lowitt MH, Kariniemi AL, Niemi KM, Kao GF. Cutaneous malacoplakia: A report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34(2 Pt 2):325-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Yuoh G, Hove MG, Wen J, Haque AK. Pulmonary malakoplakia in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: An ultrastructural study of morphogenesis of Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Mod Pathol 1996;9:476-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,628

PDF downloads

1,743