Translate this page into:

Cutaneous manifestations in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis

2 Department of Nephrology, PSG Hospitals, Peelamedu, Coimbatore, India

3 Coimbatore Kidney Centre, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Correspondence Address:

C R Srinivas

Department of Dermatology, PSG Hospitals, Peelamedu, Coimbatore

India

| How to cite this article: Udayakumar P, Balasubramanian S, Ramalingam K S, Lakshmi C, Srinivas C R, Mathew AC. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:119-125 |

Abstract

Background: Chronic renal failure (CRF) presents with an array of cutaneous manifestations. Newer changes are being described since the advent of hemodialysis, which prolongs the life expectancy, giving time for these changes to manifest. Aim: The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of dermatologic problems among patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) undergoing hemodialysis. Methods: One hundred patients with CRF on hemodialysis were examined for cutaneous changes. Results: Eighty-two per cent patients complained of some skin problem. However, on examination, all patients had at least one skin lesion attributable to CRF. The most prevalent finding was xerosis (79%), followed by pallor (60%), pruritus (53%) and cutaneous pigmentation (43%). Other cutaneous manifestations included Kyrle's disease (21%); fungal (30%), bacterial (13%) and viral (12%) infections; uremic frost (3%); purpura (9%); gynecomastia (1%); and dermatitis (2%). The nail changes included half and half nail (21%), koilonychia (18%), onychomycosis (19%), subungual hyperkeratosis (12%), onycholysis (10%), splinter hemorrhages (5%), Mees' lines (7%), Muehrcke's lines (5%) and Beau's lines (2%). Hair changes included sparse body hair (30%), sparse scalp hair (11%) and brittle and lusterless hair (16%). Oral changes included macroglossia with teeth markings (35%), xerostomia (31%), ulcerative stomatitis (29%), angular cheilitis (12%) and uremic breath (8%). Some rare manifestations of CRF like uremic frost, gynecomastia and pseudo-Kaposi's sarcoma were also observed. Conclusions: CRF is associated with a complex array of cutaneous manifestations caused either by the disease or by treatment. The commonest are xerosis and pruritus and the early recognition of cutaneous signs can relieve suffering and decrease morbidity.

|

|

|

|

Earlier diagnosis and treatment of patients with CRF improves the quality of life and prolongs the life expectancy of these patients, giving time for newer cutaneous manifestations to develop. In a study by Pico et al., all the patients with CRF had one or more skin manifestations,[1] while Bencini et al. noticed skin changes in 79% of patients.[2] Our study was conducted to determine the prevalence of cutaneous alterations in CRF patients on hemodialysis.

Methods

One hundred successive patients of CRF undergoing hemodialysis were examined for cutaneous manifestations in a tertiary hospital. Patients undergoing hemodialysis following a renal transplant failure or those who had undergone peritoneal dialysis were not included. The patients′ age, sex, primary and secondary diagnoses, medications and present cutaneous illnesses were noted. A detailed history with regard to duration of CRF, duration of dialysis, duration of skin ailment, onset of changes with relation to diagnosis of CRF and starting dialysis and improvement noticed following dialysis was recorded. Specific investigations like skin biopsy, culture and sensitivity for bacterial infections, Gram′s stain, potassium hydroxide mount and fungal culture were done where indicated, after informed consent. Routine investigations for monitoring renal functions were recorded. The severity of xerosis was assessed by a modified version of the grading by Morton[3]: grade 0 (smooth skin), grade 1 (rough skin) and grade 2 (rough skin with scaling).

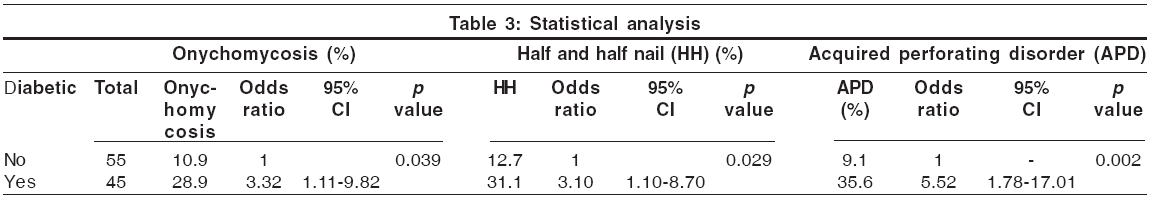

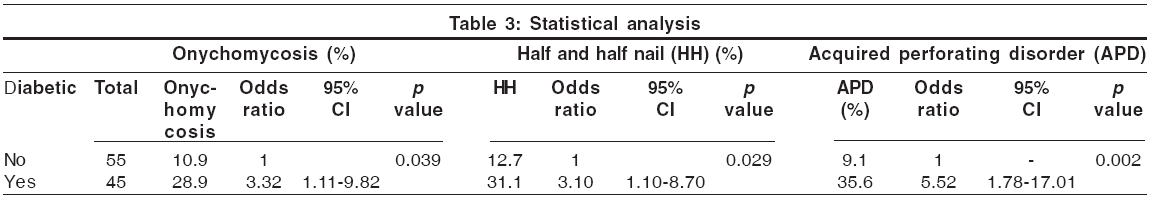

Statistical analysis was done using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. The risk (odds ratio) of onychomycosis, half and half nail and acquired perforating disorder (APD) in diabetes and associated 95% confidence intervals were estimated using logistic regression analysis with SPSS Software (11.5 version). Tests with two-sided P values were performed. p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

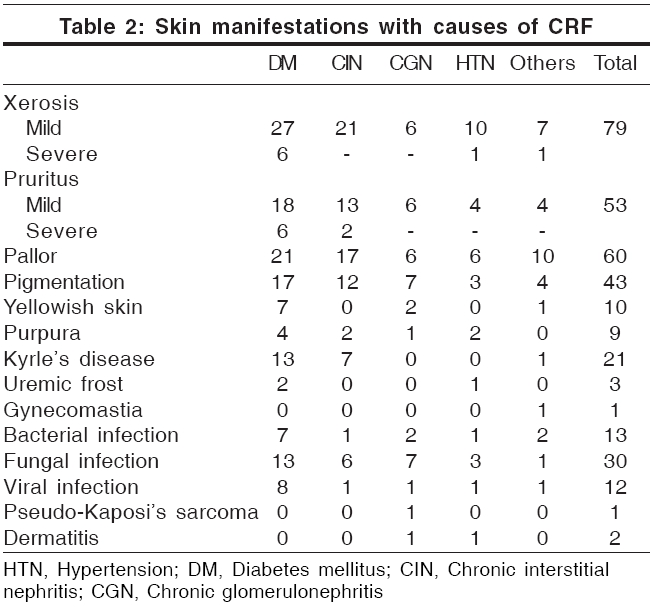

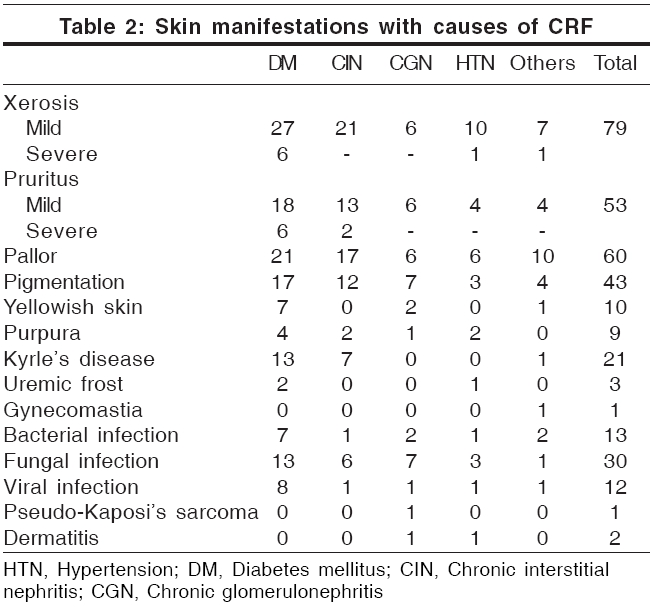

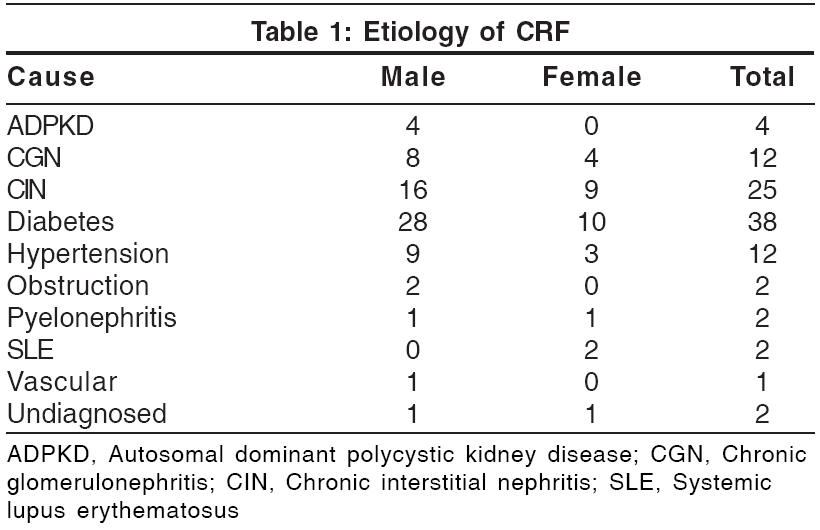

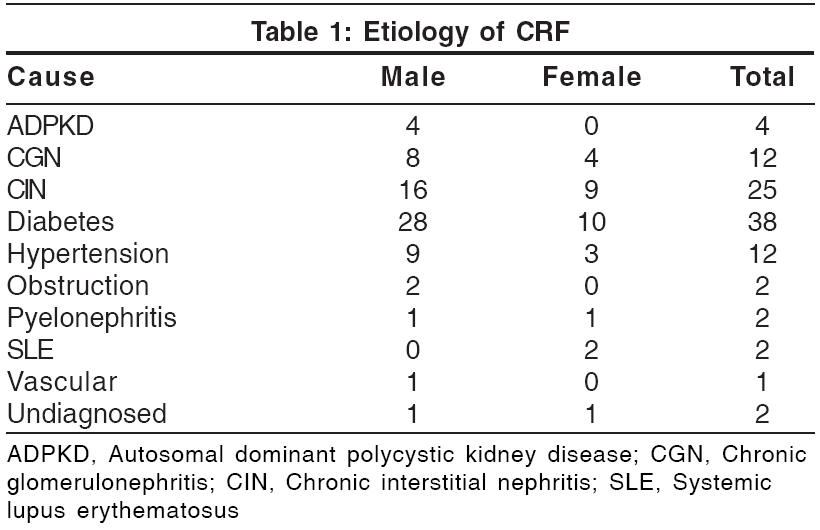

One hundred patients (70 males and 30 females) were examined. Most of them were aged between 41 and 50 years; the youngest patient was aged 10 years and the oldest, 76 years. The duration of chronic renal failure varied from 1 month to several years. The various causes leading to renal failure are shown in [Table - 1]. Nine patients had a hemoglobin level of less than 5 g%, 58 had 5.1-8 g% and 30 had more than 8 g%. Eleven patients (6 male and 5 female) were HBsAg positive; one patient was HCV positive and one HEV positive. All patients examined in the study showed at least one cutaneous manifestation, although only 82% complained of some skin problem. Skin manifestations in relation to causes of CRF are shown in [Table - 2].

Discussion

Xerosis Xerosis was the most common cutaneous abnormality (79%), as observed in previous reports (46-90%).[4],[5],[6] This was classified as mild (71%) and severe (8%). Two out of the 79 patients had hypothyroidism and had noticed dry skin prior to the diagnosis of CRF, while 4 had xerosis from childhood. Thirty-seven patients had associated keratosis pilaris-like lesions. Xerosis was predominantly seen over the extensor surfaces of the forearms, legs and thighs. The abdomen and chest showed fine scaling. Xerosis worsened in 9 patients, improved in 5 patients and was unchanged in 65 patients while on hemodialysis. It was severe in diabetics . Xerosis is a known complication of diabetes.[6] A reduction in the size of eccrine sweat glands may be contributory, although high dose diuretic regimens are also implicated.[1],[7]

Pruritus Pruritus is one of the most characteristic and annoying cutaneous symptoms of CRF.[1],[3],[8] It is not present in acute renal failure and does not necessarily subside with dialysis although it improves with kidney transplantation.[8] Its prevalence among hemodialysis patients ranges from 19 to 90%.[1] In our study, 53% of patients complained of pruritus. Fifteen (28%) patients had pruritus before the diagnosis of CRF. Thirty-eight out of 53 patients (72%) found no improvement following dialysis, 5 (9.4%) showed improvement and 10 patients (18.8%) reported aggravation after hemodialysis. It was found to be severe in diabetic patients.[4] The etiology of pruritus in CRF is unknown. However, it has been associated to the degree of renal insufficiency (urine output of < 500 ml);[1],[2] secondary hyperparathyroidism; xerosis[9]; increased serum levels of magnesium, calcium and phosphate, aluminum; increased serum levels of histamine; proliferation of nonspecific enolase-positive sensory nerves in the skin; hypervitaminoses A; and iron deficiency anemia.[4] Slowly accumulated or deposited pruritogen(s), the nature of which is uncertain, are the likely cause.[7] Increased serum histamine levels may be due to allergic sensitization to various dialyzer membrane components and due to impaired renal excretion of histamine. UVB radiation is effective in uremic pruritus.[9] It is thought to act by suppressing histamine-releasing factors in the sera of uremic patients.[10] In addition, UVB also reduces vitamin A levels in the epidermis, suggesting that increased epidermal vitamin A may be contributory.[9] Oral cholestyramine and activated charcoal are other alternatives.[9] The opioid antagonist naltrexone is reported to reduce severe intractable pruritus in hemodialysis patients,[9] but other articles have not found it to be beneficial.[9] Erythropoietin therapy can alleviate pruritus in some cases of CRF.[9] Topical capsaicin cream (0.025%)[9] and oral ondansetron, a serotonin receptor antagonist, have also been reported to be effective.[9] Recently, low dose gabapentin therapy has been tried in hemodialysis patients with good results.[11]

Pallor Pallor of the skin due to anemia, reported as the hallmark of chronic renal failure, was observed in only 60% of patients, possibly because of the darker complexion. The hemoglobin level was less than 8 g% in 64% of the patients. This is a common early finding and adds significantly to the mortality.[7]

Pigmentary changes Two types of pigmentary charges were observed: hyperpigmentation (seen in 43% of patients) and a yellowish tinge to the skin (10%). Prominent hyperpigmentation over the sun-exposed areas was seen in 26%. Other authors have reported a prevalence of 20-22%.[1],[4] Diffuse hyperpigmentation on sun-exposed areas is attributed to an increase in melanin in the basal layer and superficial dermis due to failure of the kidneys to excrete beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (b-MSH).[12] Hyperpigmented macules on the palms and soles have been reported by Pico et al. and are also attributed to increased circulating b-MSH.[1],[12] A yellowish tinge to the skin has been reported in 40% of patients by other studies[1] but was seen in only 10% of our patients, probably because their darker complexion masked the finding. It has been attributed to the accumulation of carotenoids and nitrogenous pigments (urochromes) in the dermis[13] or the presence of lipochromes and carotenoids in the epidermis and subcutaneous tissue.[14]

Acquired perforating disorders Perforating disorders such as perforating folliculitis, Kyrle′s disease and reactive perforating collagenosis have been described in CRF.[15] The term ′perforating disorder of renal disease′ or ′acquired perforating disorders (APD)′ has been used to describe the hyperkeratotic follicular papules present in these patients.[15] APD has been reported to occur in 4.5-17% of patients on hemodialysis.[1],[5],[15] We encountered Kyrle′s disease in 21 patients (21%); 19 of them had undergone dialysis for less than 6 months. These changes were significantly more prevalent in diabetic patients ( P =0.002, [Table - 3]). The association of diabetes mellitus and perforating disorders has been confirmed by earlier studies.[4] Trauma to the skin in patients with pruritus secondary to CRF could be the inciting agent in producing these lesions.[13] The unifying feature of the perforating disorders is the trans-epidermal elimination of altered dermal substances.[16] Keratotic pits of the palms and soles have also been reported in hemodialysis patients.[17]

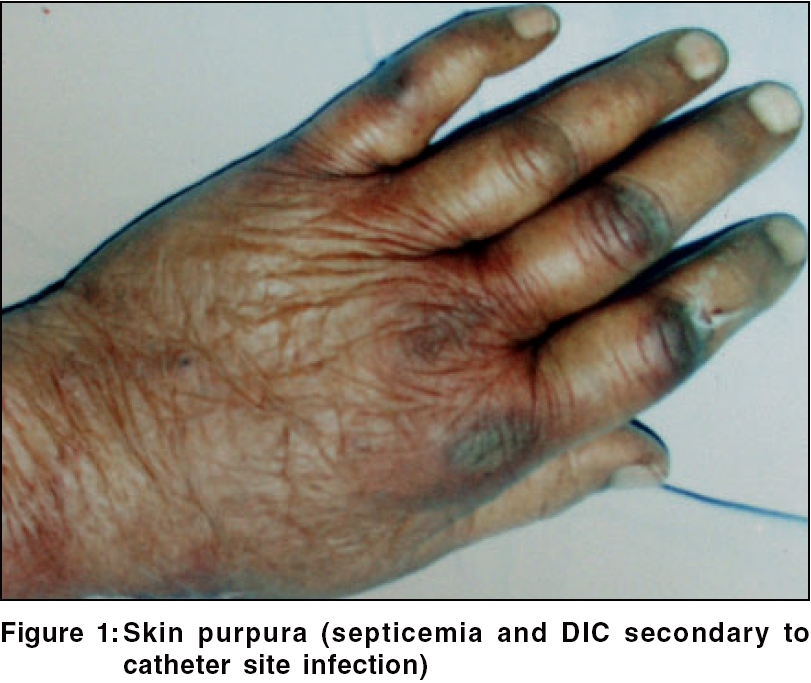

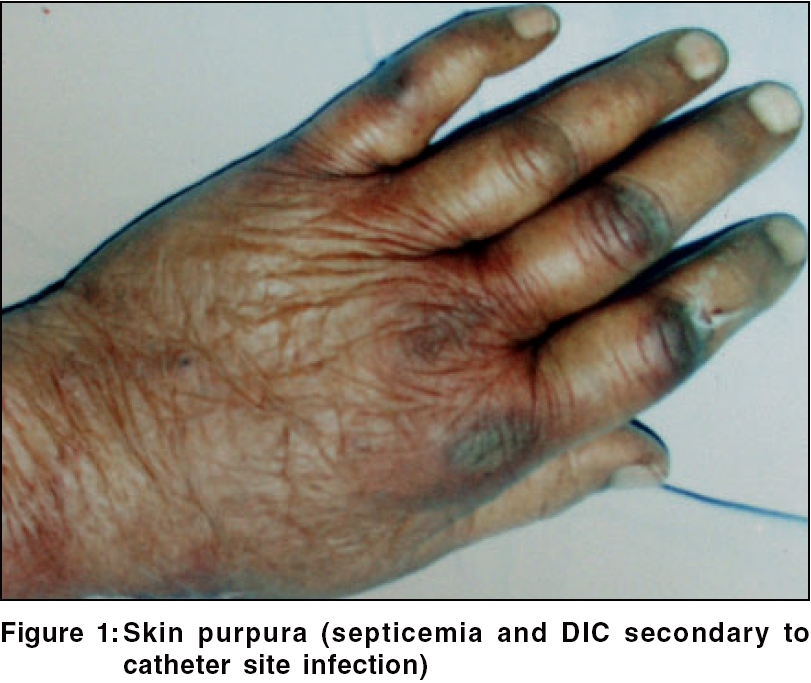

Purpura Purpura was seen in nine (9%) patients [Figure - 1]. Easy bruising was reported in a previous study. Singh observed these changes in 20% of CRF patients not on dialysis.[18] Defects in primary hemostasis like increased vascular fragility, abnormal platelet function and the use of heparin during dialysis are the main causes of abnormal bleeding in these patients.[19]

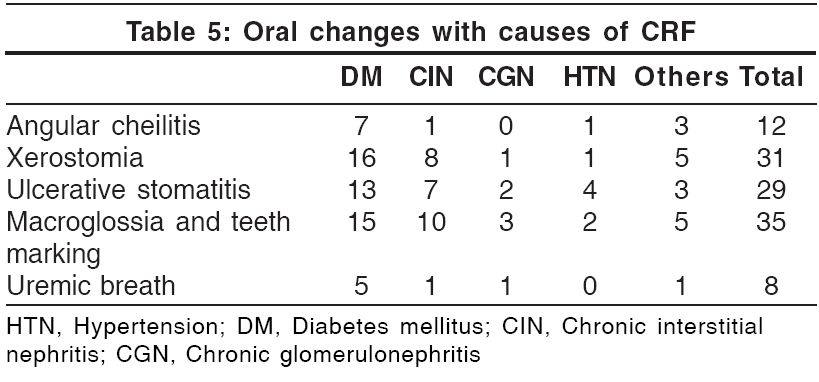

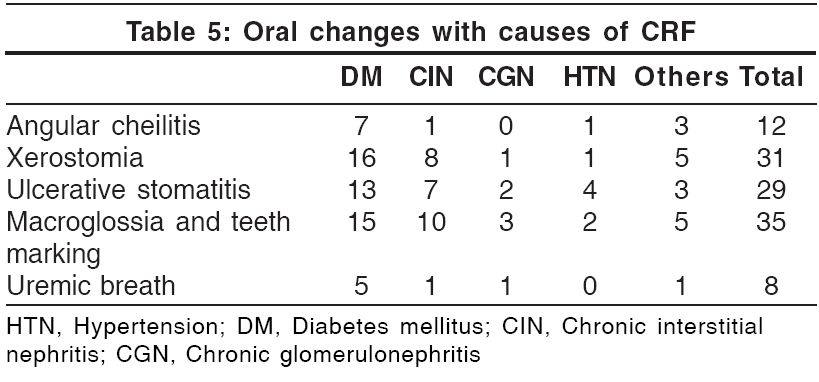

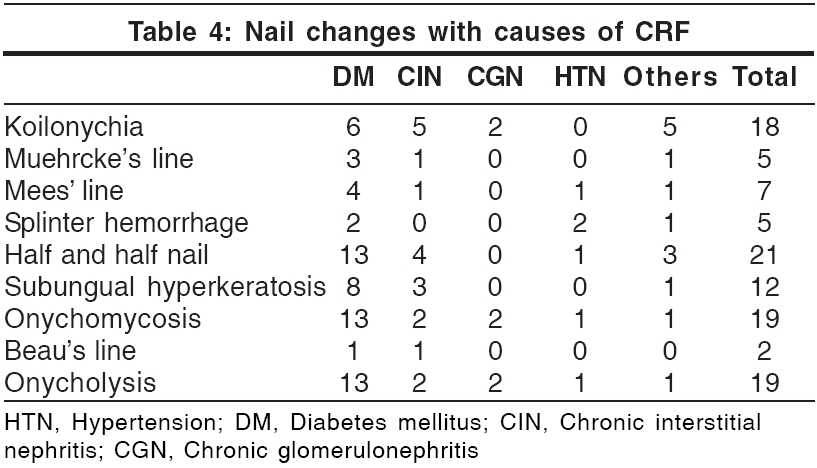

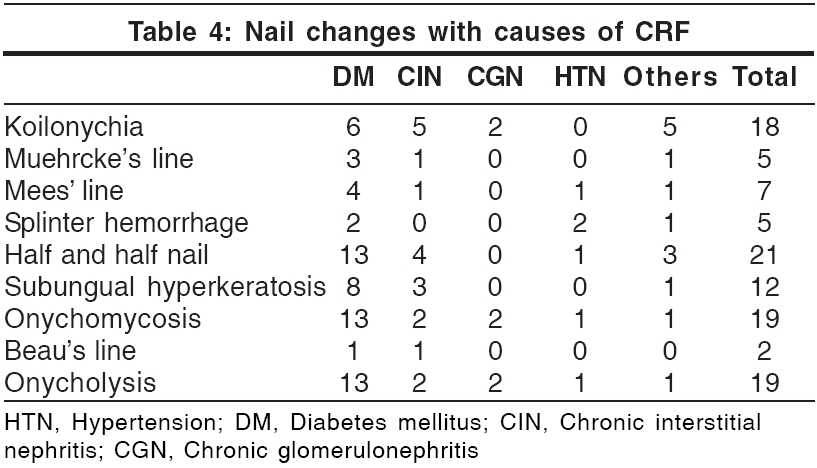

Nail changes [Table - 4] Lindsay′s nails (half and half nails) are red, pink or brown in their distal half (this color does not fade with pressure) and white in the proximal half.[17] This change was seen in 21% of our patients and was significantly more prevalent in diabetic patients (p = 0.029; [Table - 4]). Previous studies have found a prevalence of 16-50.6%.[1],[5] The prevalence in the general population has been reported to be 1.4%.[1] Other nail changes included koilonychia (18%), subungual hyperkeratosis (12%), onycholysis (10%), Mees′ lines (7%) [Figure - 2], Muehrcke′s lines (5%), splinter hemorrhages (5%) and Beau′s lines (2%). Brown nail bed arcs were not seen.

Hair abnormalities Sparse body hair and diffuse alopecia with dry, lusterless hair have been reported.[4] In our study, 30 patients had sparse body hair, 11 had diffuse alopecia and 16 had dry, lusterless hair. Dry, lusterless hair is due to decreased secretion of sebum.[20] Singh et al. have reported a prevalence of 30% in CRF patients not on dialysis.[18] Acute diffuse alopecia following a few weeks of dialysis was reported in 3 patients.[21]

Oral mucosal changes [Table - 5]

Oral mucosal changes have been reported in up to 90% patients with CRF.[22] Teeth marking with macroglossia (′tongue sign of uremia′) was seen in 35% patients. This finding was first described by Mathew in 92% of patients with CRF.[23] Xerostomia was seen in 31 patients (31%). It was attributed to mouth breathing and dehydration. Ulcerative stomatitis, seen in 29 patients, is reported to occur in patients with blood urea levels greater than 150 mg/100 ml.[22] Out of the 29 patients, 16 (55.2%) had a predialysis blood urea nitrogen level of more than 150 mg. However, 20 patients with a blood urea level of more than 150 mg/100 ml did not show these changes. This could be attributed to the poor oral hygiene of these patients.[22] Angular cheilitis was seen in 12 patients and coated tongue in 11 patients. Eight patients had uremic fetor, including 3 who had a predialysis blood urea level of more than 200 mg%. Uremic fetor is an ammoniacal odor caused by a high concentration of urea in the saliva and its breakdown to ammonia. All 3 patients died within 30 days due to inability to continue treatment. Fewer fungiform taste buds, in addition to the increased urea, contribute to the impairment of taste in CRF patients.[22],[24]

Cutaneous infection Sixty-seven skin infections (13 bacterial, 42 fungal and 12 viral), distributed amongst 40 patients, were seen in this study. Bacterial infections, seen in 13 patients, were common in diabetics. The fungal infections were distributed among 30 patients (30%). The commonest one was onychomycosis (19%), which was significantly more prevalent ( p = 0.039; [Table - 3]) in the diabetic group. Bencini et al. have reported the incidence of fungal infection in patients undergoing hemodialysis to be 67%.[2] Tinea pedis, also reported to be common,[1] was not seen in our study. CRF patients have impaired cellular immunity due to a decreased T-lymphocyte cell count; this could explain the increased prevalence of fungal infections.[1] Pityriasis versicolor was seen in 15 patients (15%). The viral infections included warts (8%), herpes simplex (3%) and herpes zoster (1%).

Uremic frost Uremic frost, one of the rarer skin changes that can occur in the acute setting of severe uremia, was seen in three patients. All of them had a pre-dialysis blood urea level of more than 200 mg / 100 ml. In the pre-dialysis era, uremic frost was a frequent dermatologic finding, but it is rarely encountered nowadays due to the wide availability of hemodialysis.[25] The frost consists of a white or yellowish coating of urea crystals on the beard area and other parts of the face, neck and on the trunk. It is due to eccrine deposition of urea crystals on the skin surface of patients with severe uremia .[25] In erythema papulatum uremicum, large papules and nodules on an erythematous base are commonly seen over the palms, soles, forearms and face. In two weeks they desquamate and develop fissures.[25] With the advent of dialysis, this change is rarely seen.

Iatrogenic manifestations Arteriovenous shunt dermatitis may be seen in 8% of patients on long-term hemodialysis.[26] One of our patients had eczema at the site of an arteriovenous fistula and another at the site of the insertion of a catheter. Pseudo-Kaposi′s sarcoma was clinically diagnosed in one patient. A few reports have described the occurrence of pseudo-Kaposi′s sarcoma near an artificially constructed arteriovenous fistula.[27] It is seen as purplish nodules or papules which slowly evolve into scaly, crusted, violaceous patches near the arteriovenous fistula. One patient developed cannula site infection and died of staphylococcal septicemia. Cannulation septicemia has been reported in 8%.[8] We saw gynecomastia in one patient, which is lower than the reported incidence (40%).[28]

Gynecomastia is not observed in uncomplicated chronic renal failure without regular treatment. It occurs during the early stages of regular dialysis treatment and is explained on the basis of ′refeeding′ after the start of treatment.[28] As a consequence of CRF and protein energy malnutrition, pituitary gonadotrophic and testicular functions remain suppressed and following treatment and increase in daily protein intake, a ′second puberty′ ensues. This may lead to transient gynecomastia. Our patient with gynecomastia was an adolescent and developed gynecomastia during the initial weeks of dialysis. The possibility of gynecomastia secondary to normal puberty cannot be ruled out. One patient developed a carbamazepine-induced maculopapular rash, which cleared spontaneously following withdrawal of the drug. There is an increased incidence of drug reactions in uremia because of administration of simultaneous admisnidtration of multiple drugs and also due to prolonged half-life of each medication.[25]

Metastatic calcification of the skin in CRF results from secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism.[17] Abnormally elevated levels of PTH trigger deposition of crystalline calcium pyrophosphate in the dermis, subcutaneous fat or arterial wall.[13] Calcified vessels may thrombose acutely, resulting in calciphylaxis, producing symmetrical livedo reticularis. Nodular calcium deposits, identical to calcinosis cutis, may occur in the skin or fat.[13]

Skin changes due to immunosuppression include an increased susceptibility to infections and development of cancerous and precancerous lesions. A prevalence of 4.5% has been reported by Bencini et al.[2],[4] Basal cell carcinoma is the commonest form of skin cancer. Multiple actinic keratoses occur over sun-exposed areas and may progress to squamous cell carcinoma.

Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD), a recently described disorder of unknown etiology, resembles scleromyxedema in some aspects.[13] Most affected patients have been on hemodialysis and many have restarted dialysis after failure of a renal transplant. NFD has also been described in a few patients with CRF. It is clinically characterized by the progressive development of erythematous, sclerotic dermal plaques, usually pruritic on the arms and legs, with sparing of the head and neck. The histopathology of NFD resembles scleromyxedema, with proliferation of fibroblasts in the dermis and subcutaneous septae accompanied by increased dermal and septal collagen and mucin.[13] There is no effective treatment.

Miscellaneous conditions Other skin lesions observed included dermatosis papulosa nigra (25), acrochordon (11), prurigo nodularis (8), idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (7), insulin induced lipoatrophy (4), vitiligo (3), diabetic dermopathy, melasma (3), fissures of the feet (3), hyperkeratosis of the sole (2), papular urticaria (2), chronic dermatitis of leg (2), seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp (2), varicose eczema (1) and Schamberg′s disease (1). The association of these changes with renal failure cannot be established.

Conclusion

All our 100 CRF patients on hemodialysis showed at least one cutaneous alteration. Patients with end stage renal failure (ESRD) may present with an array of skin abnormalities. With the advent of hemodialysis, the life expectancy of these patients has increased, giving time for more and newer cutaneous changes to manifest. Some prophylactic and remedial measures can prevent or decrease some of the adverse changes. These include emollients for xerosis; sunscreens, sun avoidance measures and clothing for pigmentary changes and cutaneous malignancies; oral hygiene to prevent oral mucosal changes; nutritional supplementation to prevent vascular fragility, angular cheilitis and hair loss; and prompt recognition and treatment of fungal infections like onychomycosis and tinea pedis, which are increased in CRF.

| 1. |

Pico MR, Lugo-Somolinos A. Cutaneous alterations in patients with chronic renal failure. Int J Dermatol 1992;31:860-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Bencini PL, Montagnino G, Citterio A, Graziani G, Crosti C, Ponticelli C. Cutaneous abnormalities in uremic patients. Nephron 1985;40:316-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Ponticelli C, Bencini PL. The skin in uremia. In: Massry SG, Glassock RJ, editors. Massry's and Glassock's Textbook of Nephrology. 2nd ed. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore; 1989. p. 1422-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Morton CA, Lafferty M, Hau C, Henderson I, Jones M, Lowe JG. Pruritus and skin hydration during dialysis. Nephron Dial Transplant 1996;11:2031-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Tawade N, Gokhale BB. Dermatologic manifestation of chronic renal failure. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1996;62:155-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Siddappa K, Nair BK, Ravindra K, Siddesh ER. Skin in systemic disease. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL Textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Bhalani Publishing House: Mumbai; 2000. p. 938-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Weisman K. Graham RM. Systemic disease and the skin. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA. Breathnach SM, editors. Rook/ Wilkinson/ Ebling Textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Blackwell Science: Oxford; 1998. p. 2703-58.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Guptha AK, Guptha MA, Cardella CJ, Haberman HF. Cutaneous associations of chronic renal failure and dialysis. Int J Dermatol 1986;25:498-504.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Etter L, Myers SA. Pruritus in systemic disease: Mechanisms and management. Dermatol Clin 2002;20:459-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Imazu LE, Tachibana T, Danno K, Tanaka M, Imamura S. Histamine-releasing factors in sera of uremic pruritus patients is a possible mechanism of UV-b therapy. Arch Dermatol Res 1993;285:423-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Manenti L, Vaglio A, Costantino E, Danisi D, Oliva B, Pini S, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of uremic atch: An index case and a pilot evaluation. J Nephrol 2005;18:86-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Smith AG, Shuster S, Thody AJ, Alvarez-Ude F, Kerr DN. Role of the kidney in regulating plasma immunoreactive beta-melanocyte stimulating hormone. Br Med J 1976;1:874-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sweeney S, Cropley TG. Cutaneous changes in renal disorders. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. Mc Graw-Hill: New York; 2003. p. 1622-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Comaish JS. Ashcroft T, Kerr DN. The pigmentation of chronic renal failure. J Am Acad Dermatol 1975;55:215-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Heilman ER, Friedman RJ. Degenerative diseases and perforating disorders. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, Johnson Jr. B, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 8th ed. Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia; 1997. p. 341-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Lebwohl M. Acquired perforating disorders. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA. Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. Mc Graw-Hill: New York; 2003. p. 1041-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Rustad OJ, Corwing VJ. Punctate keratosis of the palms and soles and keratotic pits of the palmar creases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:468-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Singh G, Singh SJ, Chakrabarthy N, Siddharaju KS, Prakash JC. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic renal failure. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1989;55:167-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Remuzzi G. Bleeding in renal failure. Lancet 1988;28:1205-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Brenner BM, Lazarus JM. Chronic renal failure. In: Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald E, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison's Principles of internal medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. p. 1274-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Kint A, Bussels L, Fernandes M, Ringoir S. Skin and nail disorders in relation to chronic renal failure. Acta Derm Venereol 1974;54:137-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Cohen GS. Renal disease. In: Lynch MA, editor. Burket's Oral medicine: Diagnosis and treatment. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. p. 487-509.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Mathew MT, Rajarathnam K, Rajalaxmi PC, Jose L. The tongue sign of CRF: Further clinical and histopathological features of this new clinical sign of chronic renal failure. J Assoc Phy Ind 1986;34:52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Astback J, Fernstrom A, Hylander B, Arvidson K, Johansson O. Taste buds and neuronal markers in patients with chronic renal failure. Perit Dial Int 1999;19:S315-S23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Scoggins RB, Harlan WR Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of hyperlipidemia and uraemia. Postgrad Med 1967;4:537-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Goh GL, Phay KL. Arterio- venous shunt dermatitis in chronic renal failure patients on haemodialysis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1988;13:1038-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Goldblum OM, Kraus E, Bronner AK. Pseudo-Kaposi's sarcoma of the hand associated with an acquired, iatrogenic arterio-venous fistula. Arch Dermatol 1985;121:1038-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Lindsay RM, Briggs JD, Luke RG, Boyle IT, Kennedy AC. Gynecomastia in chronic renal failure. Br Med J 1967;4:779-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

11,531

PDF downloads

3,863