Translate this page into:

Cutaneous manifestations of chikungunya during a recent epidemic in Calicut, north Kerala, south India

2 Department of Pediatrics, Medical College, Calicut, Kerala, India

3 Department of Microbiology, Medical College, Calicut, Kerala, India

4 Department of Pathology, Medical College, Calicut, Kerala, India

Correspondence Address:

Najeeba Riyaz

Arakkal, Chalapuram, Calicut, Kerala 673002

India

| How to cite this article: Riyaz N, Riyaz A, R, Abdul Latheef E N, Anitha P M, Aravindan K P, Nair AS, Shameera P. Cutaneous manifestations of chikungunya during a recent epidemic in Calicut, north Kerala, south India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;76:671-676 |

Abstract

Background: There was a recent epidemic of chikungunya (CKG) in Calicut and other northern districts of Kerala, South India, affecting thousands of people. Aims: To study the cutaneous manifestations of CKG and to have a serological and histopathological correlation. Methods: A total of 162 patients (63 males and 99 females) with cutaneous manifestations of CKG were enrolled in the study and serological confirmation was done with capture IgM ELISA for CKG. Skin biopsy was done in all representative cases. Results: Cutaneous manifestations were found more in females. There were 23 children, the youngest being 39 days old. Generalized erythematous macular rash was the most common finding. Vesicles and bullae were also common especially in infants. Localized erythema of the nose and pinnae, erythema and swelling of the pre existing scars and striae and toxic epidermal necrolysis-like lesions sparing mucosae were the other interesting findings. Different types of pigmentation were observed with a striking nose pigmentation in a large number of patients, by looking at which even a retrospective diagnosis of CKG could be made. Hence we suggest this peculiar pigmentation may be called "chik sign". There was flare up of existing dermatoses like psoriasis, lichen planus and unmasking of Hansen's disease with type 1 reaction. Serological tests were positive in 97%. Some hitherto unreported histopathologic findings like melanophages in the erythematous rashes were observed. Conclusion: A spectrum of cutaneous manifestations of CKG with a wide variety of unusual presentations with confirmed serological and histopathological evidence was encountered.Introduction

′Chikungunya′ (CKG) owes its origin to ′Kungunyala′, a word derived from the Makonde language of Tanzania, which means "that which bends up", relating to the stooped posture adopted by these patients due to incapacitating polyarthralgia or arthritis. It is caused by Alpha virus which belongs to the family Togaviridae, a Class 4 arbo virus transmitted by the Asian tiger mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. The Alpha virus genus consists of 30 species of arthropod borne viruses. [1] Of these, six mosquito borne viruses are associated with fever, arthralgias and rash: the Ross River and Burma Forest viruses in the South Pacific, O′nyong-nyong and Sindbis viruses in tropical Africa, Chikungunya virus (CHIK V) in Africa and Asia, and Mayaro virus in South America.

CKG was first reported in 1953 from Tanzania. Major epidemics of CKG occur cyclically, and a disease free period of several years or decades may exist between the outbreaks. The first reported outbreak of CKG in India was from Calcutta city in 1963. CKG made its first appearance in South India in 1964. [2] A small outbreak was later reported from Sholapur district in Maharashtra in 1973. After a period of quiescence, there was a re-emergence of CKG epidemic in some islands of the Indian Ocean - La Reunion, Mauritius and Seychelles in February 2005 affecting 2, 66,000 people in Reunion Island. [2] Re-emergence of the epidemic was noted in South India in December 2005. In Kerala, a state in South India, the first outbreak of CKG was in May 2006 affecting nearly 70,000 people from all the 14 districts. There was another outbreak in May 2007. [3] The present epidemic was mainly in the three northern districts of Kerala (Calicut, Malappuram and Kannur) which commenced around January 2009 and lasted till the end of October affecting thousands of people.

Here, we report the varied and unusual cutaneous manifestations of CKG encountered in Calicut district, Kerala state, South India.

Methods

Patients attending the OPD of Dermatology and Pediatrics of Calicut Medical College, and those who attended the camps organized at the suburban areas of Calicut during the recent epidemic of CKG from July 2009 to the end of September, were included in the study. It was a prospective, descriptive study. Diagnosis of CKG was made based on the criteria put forth by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, Directorate General Health Services, India. [2] These included patients presenting with an acute illness characterized by the sudden onset of fever with joint pain, headache, backache and eruption during an epidemic of CKG and confirmed by serology. A total of 162 cases were included in the study. IgM capture ELISA specific for CKG virus (kit obtained from NIV, Pune) was done in all cases from our microbiology department, Skin biopsy was done from selected patients having similar lesions. Other investigations included hemogram, ESR, platelet count, bleeding time, clotting time, urinalysis, blood sugar, bacterial culture, liver and renal function tests, serum electrolytes, and rheumatoid factor in relevant cases.

Results

Out of 162 patients, females 99(61.11%) outnumbered males 63(38.88%). The youngest patient was only 39 days and the oldest was a 78 -year -old man. Maximum patients were in the 30-40 year age group, the mean age being 34.25 years. There were 23 children out of which 12 were infants.

Presentations other than fever included joint pain (65.6%), edema of hands and feet (49.6%), seizures (1.6%) and loose stools (0.8%).

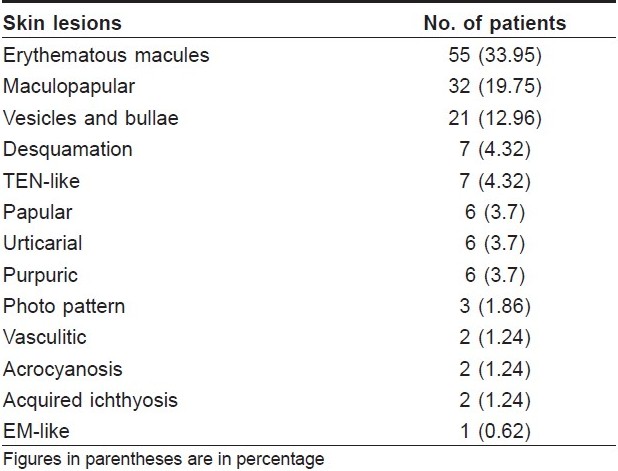

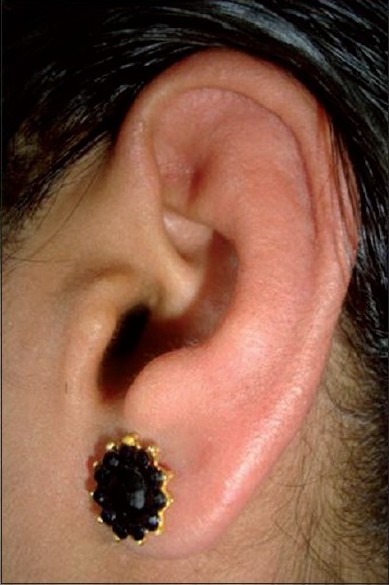

Cutaneous lesions are shown in [Table - 1]. Patients presented with either a single lesion or a combination of lesions. The most common skin lesion was erythematous rash in 94 (58%) patients of which the macular rash predominated in 55(33.95%). Most of the skin lesions developed during the acute phase of the disease, two-three days after the onset of fever (74.16%). Skin lesions along with fever were observed in 10.08% and preceded fever in 3.6%. Localized erythema and swelling of the pinnae mimicking the Milian′s ear sign of erysipelas [Figure - 1] was an interesting observation in seven patients. Similarly, erythema and edema of BCG scar and pre-existing post traumatic scars and striae resembling the ′scar phenomenon′ of sarcoidosis [Figure - 2] were seen in four patients. These findings are hitherto unreported. Other lesions were vesicles and bullae over the extremities in 21 (12.96%). A few infants 7(4.32%), had an entirely different presentation with charring, vesicles and bullae, followed by peeling, clinically mimicking toxic epidermal necrolysis but without mucosal involvement.

|

| Figure 1 :Erythema and swelling of pinna mimicking Milian's sign |

|

| Figure 2 :Erythema and swelling of abdominal striae-mimicking "scar phenomenon" |

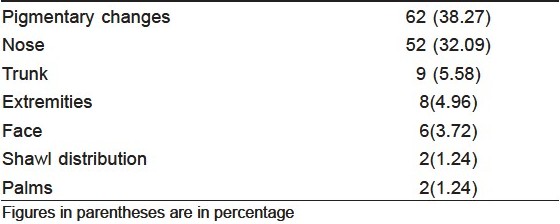

Oral mucosal involvement was found in 22 (13.64%) patients in the form of multiple aphthae, erosions, and cheilitis. Bilateral involvement of conjunctiva was present in 14 (8.64%). Nasal erosions were seen in 8 (4.94%) patients. Two patients (1.24%) had scrotal ulcers. Mucosal lesions lasted for 7-10 days and subsided completely without any sequelae. The peculiar nail findings noted in our study were black lunulae, diffuse and longitudinal melanonychia, transverse pigmented bands in two patients each and a single case each of leukonychia and onychomadesis which have not been reported so far. Skin lesions subsided without any sequelae in the majority, except pigmentation in 62 patients (38.27%). Various types of pigmentation were observed [Table - 2], the most common site being the nose.

Monocytosis was observed in 13 infants (8.04%). No other hematological abnormality was detected. Serology for IgM CKG was positive in all except five patients.

Discussion

CKG is a re-emerging viral infection clinically characterized by an acute febrile illness with incapacitating polyarthralgia, headache, vomiting, sore throat, conjunctivitis and skin eruptions. It is usually self limiting and rarely fatal. [4] The reasons for the re-emergence of CKG in the Indian subcontinent are unclear. Globalization of trades and increased international travel, the abundance of potential vectors like the Aedes mosquitoes, poor vector control, absence of herd immunity and viral mutation may be the contributory factors. [5]

CKG may be seen in all age groups and both sexes as in our study affecting a 39 -day -old infant to a 78-year- old man. Vertical or materno-fetal transmission of CKG has been observed in an outbreak at La Reunion island, [4],[6] but there was no evidence of it in our study. The serology of the mothers of affected children was negative. Females outnumbered males whereas males predominated in other studies. [5],[7] Both sexes were equally affected in another study. [8]

The most common cutaneous lesion described in CKG is erythematous maculopapular rash affecting the trunk, limbs and face. [2],[5] Erythematous macules were the most common presentation in our study which developed abruptly after the first two days of fever and subsided within four-five days. Skin manifestations have been reported in 77% of patients during the first week by Hochedez et al.[1] which spared the face and involved mainly the trunk and limbs with islands of normal skin. Morbilliform rash involving the upper extremity was the most common type in another study. [8] Majority of our patients had generalized lesions, except in 15% who had localized erythema of the nose. Transient nasal erythema has been reported. [7] Recurrent crops of lesions can occur as a result of intermittent viremia. [2],[5] These exanthems were associated with edema of hands and feet in 62 of our patients similar to the observation by others. [1],[2] In most of the cases, skin lesions subsided without any sequelae except in 10 patients who developed severe palmo plantar and facial desquamation. Pruritus has been reported in 80.8% of patients, [3] whereas it was present in 70% of our patients.

There was a significant difference in the clinical presentation of CKG in infants and adults in our study. Infants had an abrupt onset of fever lasting for only one day followed by the development of maculopapular rash. Vesicles and bullae were seen in 21 patients of which seven were infants. These lesions developed mostly by fourth day. In a pediatric case series of CKG infection during the 2005-2006 outbreak in La Reunion Island, extensive bullous lesions in 13 infants have been reported. [9] Blistering developed two days after the onset of fever and affected 21.5% of the total body area. RT-PCR of the blister fluid was positive with a mean viral load higher than the concurrent serum. In our series, seven infants presented with spotty discrete and confluent charred macules and flaccid bullae followed by peeling, resembling TEN [Figure - 3]. But mucosae were strikingly spared and the lesions subsided in three-four days. There was no history of any drug intake prior to such lesions. Kannan et al.[3] also had noticed significant difference in the presentation in infants. Symmetrical superficial vesiculobullous lesions and acrocyanosis without any hemodynamic alterations were noted in most infants by Valamparambil et al. [5] Acrocyanosis was present in two of our infants who were severely ill.

|

| Figure 3 :Charring, flaccid bullae and peeling |

Hemorrhagic manifestations have been reported to be 11% in CKG but the severity is much less. In Inamdar′s series, multiple ecchymotic patches and subungual hemorrhages were noted in six children and three adults. [7] Petechiae were noted in four of our patients which is similar to the study by Kannan et al. [3] Two patients had erythema multiforme-like lesions. It may be due to a reactive phenomenon to CKG virus.

Multiple aphthae-like lesions affecting oral cavity, intertriginous areas, axillae and scrotum have been documented. [3],[5],[7],[8] Aphthae-like erosions, ulcers and cheilitis were observed in 17.8% of our cases. Tender, discrete and oval aphthae-like ulcers of 1-1.5 cm size, with irregular margins on the peno-scrotal junction were observed in two patients whereas it was the predominant finding in other studies. [2],[7],[10] Bacterial culture from the ulcer did not grow any organism.

Different types of pigmentation have been reported in CKG. It was the most common presentation in one study [7] and the second most common in our study. Nose was the most common site affected [Figure - 4], as noticed by others also. [11],[12] Pigmentation was macular, and a few of them had pin point (confetti) macules. Other patterns of pigmentation were melasma-like over the face, periorbital melanosis, irregular and flagellate patterns on the trunk, extremities, and abdomen and an Addisonian type of palmar pigmentation. The onset, evolution and histopathology was similar in all types of pigmentation. Pigmentation developed two weeks after the rash in most of our cases but the earliest was on the fourth day. The melasma-like lesions mimicked exactly true melasma in morphology and histology except for perivascular infiltrate. Mechanism of pigmentation could be post inflammatory. [5] An increased intraepidermal melanin dispersion /retention triggered by the virus has been postulated as a cause for pigmentation. [7]

|

| Figure 4 :Nose pigmentation |

Nail changes may be secondary to inflammation of the nail matrix, reduced adrenocortical activity secondary to infection. [10]

Exacerbation of existing dermatoses has been well documented in CKG. [7] Fourteen psoriatic patients including one pustular psoriasis who were free of the disease developed a recurrence following CKG. One patient developed psoriatic arthritis for the first time in a rheumatoid pattern. But his rheumatoid factor was negative. Interestingly 50% of psoriatic patients developed nose lesions for the first time. They also developed cheilitis. Lichen planus, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis alba, allergic contact dermatitis and stasis eczema aggravated following CKG. Unmasking of Hansen′s disease with type 1 reaction and pemphigus vulgaris was also observed during the acute stage.

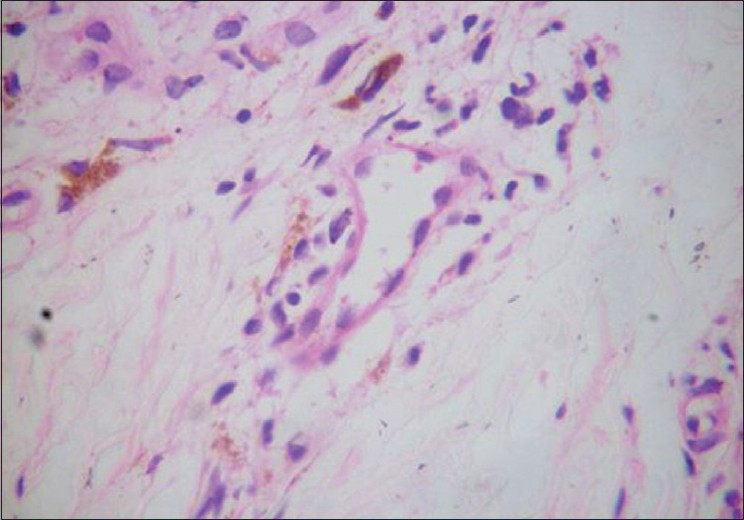

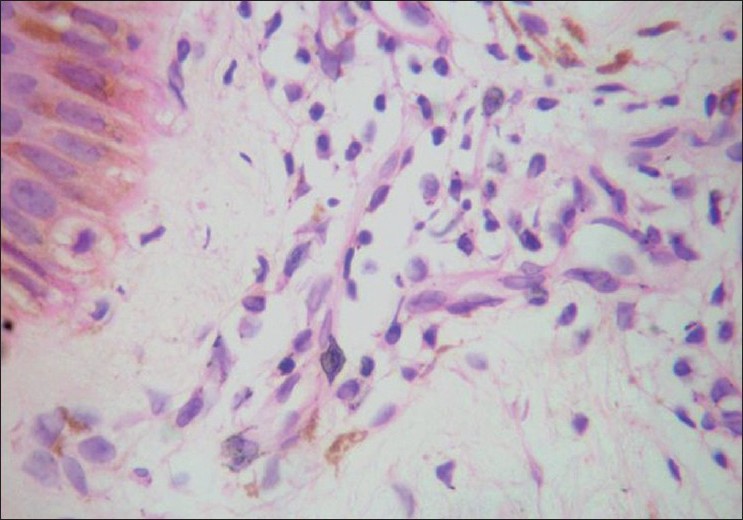

Histopathology was done in selected cases. The characteristic findings in the erythematous rashes were spongiosis, dermal edema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in different types of lesions of CKG has been documented. [13] Another interesting finding, hitherto unreported, was the presence of melanophages in these lesions [Figure - 5].The hyperpigmented lesions on the nose, malar area and other pigmented areas showed a unique histology of increased basal pigmentation, pigmentary incontinence and melanophages [Figure - 6] as observed by others. [11],[13] But a perivascular infiltrate was also present in these lesions. Melanophages have not been found in Inamdar′s series. [7] Biopsy from the vesicles and bullae revealed marked hydropic degeneration of basal cells with pigmentary incontinence, subepidermal cleavage and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils. Another biopsy from charred lesion revealed intraepidermal cleavage with necrotic keratinocytes, basal cell degeneration and mild periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate. Presence of both intra and subepdermal cleavage may indicate the variations in severity of cytopathic effect. Histopathology from the scrotal ulcer also showed dermal edema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Spongiosis and neutrophilic infiltration of vessels in the dermis were observed in erythema multiforme like lesions.

|

| Figure 5 :Melanophages and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in erythematous macules (H and E, ×40) |

|

| Figure 6 :Increased basal pigmentation with melanophages and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in pigmented macules (H and E, ×40) |

Serology was positive for IgM antibody in 97% of cases. It was negative in 3% probably because the blood samples were sent too early. In humans CHIKV produces disease about 48 h after mosquito bite followed by high viremia in the first two days of illness. [5] Viremia declines by three-five days followed by the appearance of hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and neutralizing antibodies (NA). Protection and recovery of CKG in humans are thought to be mainly mediated by neutralizing antibody response directed at the envelope glycoprotein. Positivity of IgM CKG antibodies has been reported in 40.13% of patients. [8] IgM antibody may persist for two-six months. Virus isolation is possible during the period of viremia (2-10 days) by inoculation of serum on vero or mosquito cells and identification by immunofluorescence.

Apart from the clinical manifestations, little is known about the pathogenesis of CKG in humans. The myriads of cutaneous lesions right from macular erythema to necrotic and vasculitic lesions may represent a spectrum of vascular changes induced by CHIKV, ranging from vasodilatation to severe vascular endothelial damage. The initial manifestation in any viral exanthem is attributed to viremia and dissemination of virus into the skin resulting in a direct cytopathic effect leading to epidermal, dermal or dermal capillary endothelial injury. It may be due to a combination of direct cytopathic effect and immunological factors. [14] The purpuric lesions may be due to thrombocytopenia induced by the virus, [14] or viral replication in the capillary endothelium causing a direct vascular damage or by a type 3 immune reaction. [15] No abnormalities of bleeding time or clotting time were observed in our patients. Vesicles may result from viral replication in the epidermis causing focal necrosis, ballooning degeneration, or nuclear disruption followed by an immune response and infiltration by leucocytes. [14],[15] Histological evidence of vasodilatation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and varying degrees of vascular damage in different types of skin lesions and features of neutrophilic vasculitis in the cutaneous vasculitic lesion point toward the vascular effects of CHIKV.

Conclusion

A bewildering array of cutaneous manifestations with a wide variety of unusual presentations, some hitherto unreported, has been observed in a recent epidemic of CKG. These include erythema and swelling of the pinnae mimicking the Milian′s ear sign of erysipelas, erythema and edema of preexisting scars and striae resembling ′scar phenomenon of sarcoidosis′, varying nail changes and histopathological findings of melanophages not only in pigmented lesions but also in erythematous rashes. The ever expanding and newer manifestations of CKG with each epidemic may be explained by the wider sequence diversity and genetic micro evolutions of the viral strains during the course of an epidemic. [5] The abundance of Aedes albopictus and mutations in glycoprotein envelope (E1) gene of CHIKV may be the contributory factors for repeated outbreaks. [16]

Nose pigmentation was striking in several cases of CKG which has not been reported in any other viral exanthem, to the best of our knowledge. Its presence and persistence for about three-six months after an attack of CKG helps to make a clinical and retrospective diagnosis of CKG. Hence, this may be considered as a marker of CKG, and we suggest ′chik sign′ for this peculiar pigmentation.

| 1. |

Hochedez P, Jaureguiberry S, Debruyne M, Bossi P, Hausfater P, Brucker G, et al. Chikungunya Infection in travelers. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:1565-67.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

World Health Organization. Chikungunya and Dengue in South West India. Occurrence, Epidemic and Pandemic. Response 17 March 2006 Available at http://www.who.int/esr/don/2006-03-17/en/index/html. [Last accessed on Oct10 2007].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kannan M, Rajendran R, Sunish TP, Balasubramaniam R, Arunachalam N, Paramasivam R, et al. A study on Chikungunya outbreak during 2007 in Kerala South India. Indian J Med Res 2009;129:311-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Chhabra M, Mittal V, Bhattacharya D, Rana V, Lal S. Chikungunya fever. A re-emerging viral infection. Indian J Med Microbiol 2008;26:5-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Valamparambil JJ, Chirakkarot S, Letha S, Jayakumar C, Gopinathan KM. Clinical profile of Chikungunya in infants. Indian J Pediatr 2009;76:151-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Robillard PY, Boumakni B, Gerardin P, Michault A, Fourmaintrause A, Shuffenecker I, et al. Vertical maternal fetal transmission of the Chikungunya virus. Press Med 2006;35:785-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Inamdar AC, Palit A, Sampagavi NV, Raghunath S, Deshmukh NS. Cutaneous manifestations of Chikungunya fever. Observations made during a recent outbreak in South India. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:154-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh SK. Mucocutaneous features of Chikungunya fever: A study from an outbreak in West Bengal India. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:1148-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Robins S, Ramful D, Zettor J, Benhamou L, Jaffar BMC, Riviere JP, et al. Severe bullous skin lesion associated with Chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:67-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Mishra K, Rajawat V. Chikungunya induced genital ulcers. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:383-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Shivakumar V, Rajendra O, Rajkumar V, Rajasekhar TV. Unusual facial melanosis in viral fever. Indian J Dermatol 2007;52:116-17.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Prashant S, Kumar AS, Mohammed Basheeruddin DD, Chowdhary TN, Madhu B. Cutaneous manifestations in patients suspected of Chikungunyadisease. Indian J Dermatol 2009;54:128-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Swaroop A, Jain A, Kumhar M, Parihar N, Jain S. Chikungunya fever. J Indian Acad Clin Med 2007;8:164-68.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Ralph D Feigin, James D Cherry. Textbook of Paediatric Infectious Diseases. 4 th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998. p. 720-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Rook′s Textbook of Dermatology. 7 th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004. p. 254-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Kumar NP, Joseph R, Kamaraj T, Jambulingam P. A 226 V mutation in virus during the 2007 Chikungunya outbreak in Kerala. Indian J Gen Virol 2008;89:1945-48.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

13,578

PDF downloads

2,545