Translate this page into:

Dermatoscopy of non-melanocytic skin tumors

Correspondence Address:

Engin Senel

�ankiri State Hospital, Clinic of Dermatology, �ankiri

Turkey

| How to cite this article: Senel E. Dermatoscopy of non-melanocytic skin tumors. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:16-22 |

Abstract

Dermatoscopy is a cheap and non-invasive diagnostic technique that improves the diagnostic accuracy of non-pigmented benign and malignant skin tumors. Dermatologist should be aware of dermatoscopic features of non-melanocytic skin tumors to reach the correct diagnosis.Introduction

Dermatoscopy (also known as dermoscopy, incident light microscopy, epiluminescence microscopy and skin-surface microscopy) is an inexpensive in vivo and non-invasive technique that permits the visualization of morphologic features that are not visible to the naked eye. [1] Although a 10-fold magnification is sufficient for the assessment of the suspicious skin lesions, magnifications in various dermatoscopy instruments range from 10Χ to 100Χ. Dermatoscopy is widely used currently for the diagnosis of pigmented and non-pigmented skin lesions.

There are conflicting data in the literature regarding the history of dermatoscopy. Johan Christophorus Kolhaus investigated small vessels in the nail bed using a microscope in 1636. In 1893, Unna used oil immersion to make the skin more transparent and examined lupus vulgaris lesions. [2] The German dermatologist, Johann Saphier, published four reports on his method adding a built-in light source to the dermatoscope in 1920 and 1921. He was the first to use the term "dermatoscopy". In the 1950s, Goldman coined the term "dermoscopy". [3]

Dermatoscopy helps in the diagnosis of many pigmented skin lesions such as seborrheic keratosis (SK), pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), hemangioma, blue nevus, atypical nevus, and cutaneous melanoma. It is 10-27% more sensitive than clinical criteria of ABCD (asymmetry, border regularity, color distribution, and diameter) in the early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. [4],[5] Dermatoscopy of melanocytic lesions increases the presurgical accuracy rate of clinical diagnosis from 50 to 85%. [6],[7]

The accuracy of clinical diagnosis of pigmented Spitz nevi improved from 56 to 93% by using dermatoscopy. [8],[9] Demirtasoglu et al. found that dermatoscopy raised the rate of diagnostic accuracy for pigmented BCC from 60 to 90% and reported that dermatoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of pigmented BCC. [10] Use of the dermatoscopic methods by experienced physicians increases clinical diagnostic accuracy for hemangioma and angiokeratoma by 87-100%. [11],[12]

Correlation between the dermatoscopic and histopathologic features of the non-melanocytic skin tumors has not been a highly studied area of dermatoscopy practice. Cabrijan et al. reported a 72.8% correlation between histopathology and dermatoscopy in diagnosing skin tumors. [13] Corresponding histopathologic findings can be predicted by means of dermatological examination in pigmented BCC. [14] Warshaw et al. reported that the addition of dermatoscopic images to clinical images increased the diagnostic accuracy in teledermatologic evaluation of malignant non-melanocytic lesions. [15]

Basal cell carcinoma

BCC is the most common type of skin cancer in humans. [16] It originates from the basal layer of the epidermis. Non-pigmented BCCs are much more common than pigmented BCC. [17] In the dermatological examination, non-pigmented BCCs can be easily distinguished from any other skin lesion by their asymmetrical arborizing vessels, pink color, and focal ulceration [Figure - 1]. [18] White regression areas may be seen. [19]

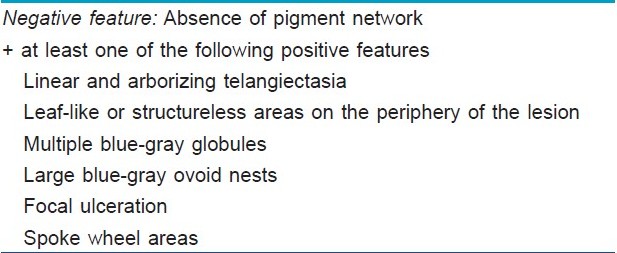

|

| Figure 1 :Dermatoscopy of non-pigmented BCC – pink color, absence of pigment network, and arborizing vessels |

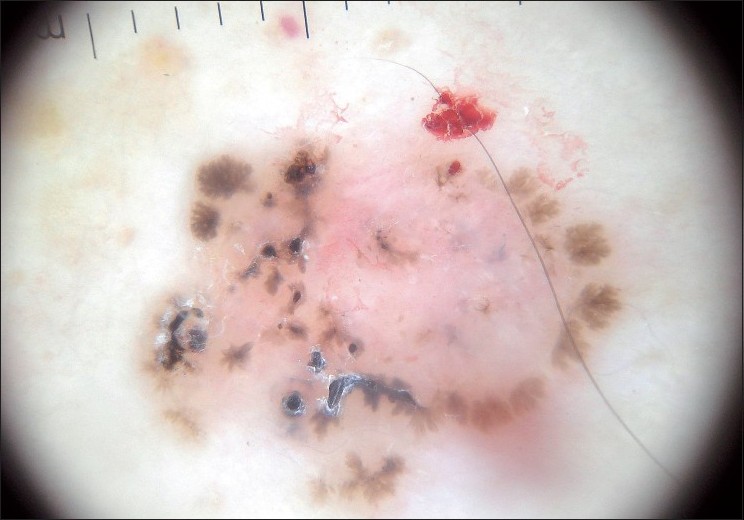

Pigmented BCCs sometimes can be difficult to distinguish clinically from melanoma. Dermatoscopy has been proven to be a useful diagnostic tool to distinguish pigmented BCC from other pigmented lesions. [19],[20],[21],[22] Menzies et al. proposed a simple dermatoscopic method for diagnosing pigmented BCCs. This method has a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 89%. In this diagnostic method, a pigmented BCC to be diagnosed must have the negative feature (absence of pigment network) and at least one of the positive features [Figure - 2] and [Table - 1]. [21]

|

| Figure 2 :Dermatoscopy of pigmented BCC – structureless areas at the lesion periphery, leaf-like structures, absence of pigmented network, blue-gray globules |

Seborrheic keratosis

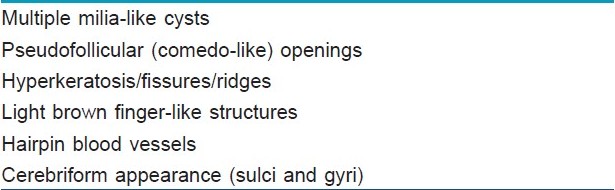

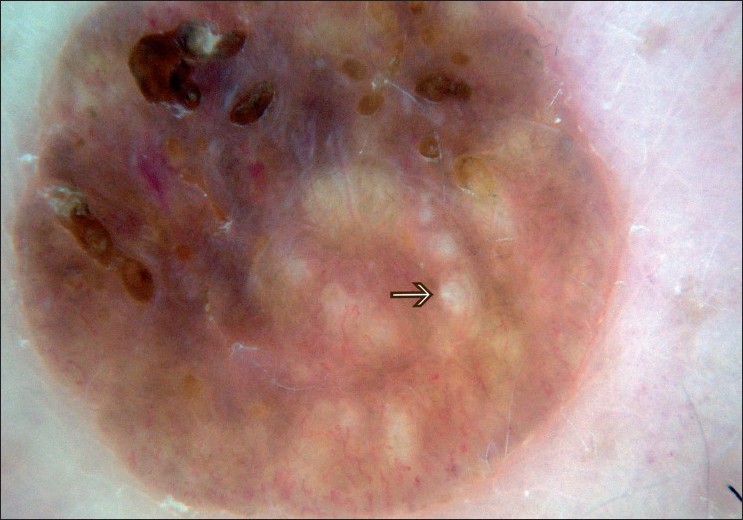

SK is a common benign skin tumor seen mostly amongst the elderly population. [23],[24] Although diagnosis of SK is generally a clinical diagnosis, sometimes the differentiation between SK and cutaneous melanoma may be difficult in the clinical aspect. Braun et al. reported the frequencies of the dermatoscopic structures in SK in a study with 203 patients. [25] Although the classical dermatoscopic criteria of SK that include multiple milia-like cysts and comedo-like openings had a high prevalence, additional structures such as hairpin blood vessels, fissures, sulci and gyri improved the diagnostic accuracy [Figure - 3],[Figure - 4],[Figure - 5]. [25],[26] The dermatoscopic features of SK are easily distinguishable but nonspecific [Table - 2]. [25],[26],[27]

|

| Figure 3 :Dermatoscopy of SK – milia-like cysts |

|

| Figure 4 :Dermatoscopy of SK – hyperkeratosis with fissures and ridges |

|

| Figure 5 :Dermatoscopy of SK – cerebriform appearance (sulci and gyri) |

Actinic keratosis

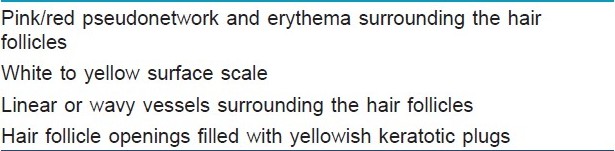

Actinic (solar) keratosis (AK) is a direct precursor of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and caused by chronic exposure of UV radiation of sunlight which induces abnormal proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes. [28],[29] AK can be pigmented or non-pigmented. Facial AK is a differential diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma (lentigo maligna) since pigmented facial AK may have a broken-up pseudonetwork. [28],[29],[30],[31],[32] Pseudonetwork can be observed in dermatoscopic examination of certain benign pigmented facial lesions such as AK, ephelide, and junctional nevus. Zaluadek et al. observed four essential dermatoscopic features in facial AK and defined the combination of these features as "strawberry" pattern [Table - 3] and [Figure - 6]. [33]

|

| Figure 6 :Dermatoscopy of AK – white surface scale, erythema, pseudonetwork |

Sebaceous hyperplasia

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a benign proliferation of sebaceous lobules around the follicular infundibulum. [36],[37] Yellow nodules surrounding a central follicular opening can be seen in dermatoscopic examination [Figure - 7]. Sebaceous hyperplasia must be differentiated from small non-pigmented BCC. Dermatoscopic examination of sebaceous hyperplasia can reveal vessels that extend to the center of the lesion but they are never arborizing. [1]

|

| Figure 7 :Dermatoscopy of sebaceous hyperplasia – central follicular opening and surrounding yellow lobule |

Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma, also known as fibrous histiocytoma, is a common benign fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal growth of the skin. The etiology of dermatofibroma remains unclear. [38],[39] Dermatofibromas clinically exhibit "dimple sign" with lateral depression in the overlying skin. [40],[41] Since dermatofibromas may mimic other skin tumors including melanoma, the definition of their dermatoscopic features is crucial [Figure - 8] and [Table - 4]. In a recent study of 412 dermatofibromas (from 292 patients), 10 different dermatoscopic patterns were observed. The most common dermatoscopic pattern seen in the study group was central white patch and peripheral pigment network (34.7%). [35]

|

| Figure 8 :Dermatoscopy of a typical dermatofibroma – central scar-like patch and peripheral delicate network |

Squamous cell carcinoma

The dermatoscopic features of SCC are a non-specific pattern with scales and grouped glomerular blood vessels surrounded by a whitish halo. [13],[18],[42] A scaly surface, brown globules and glomerular vessels can be seen in the dermatoscopic examination of pigmented Bowen′s disease. Differential diagnosis between pigmented SCC and melanocytic lesions is difficult in some cases. Pigmented SCC can present a dermatoscopic pattern resembling melanocytic lesions with globules, radial streaks and homogeneous blue pigmentation and can lead a physician to a wrong diagnosis. [43]

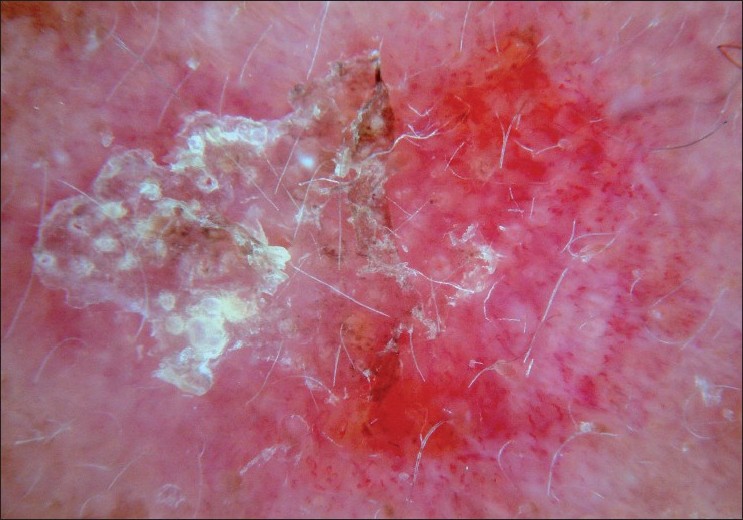

Clear cell acanthoma

Clear cell acanthoma (CCA) is a rare, asymptomatic, slowly growing, benign epidermal tumor and characterized by pink or brown nodules or plaques with a "stuck on" appearance as collarette scaling. [44] CCA frequently develops on the legs of elderly people. Dermatoscopic pattern of CCA is described. Dermatoscopic findings of CCA are homogenous, symmetrically or bunch-like arranged pinpoint-like capillaries. Dermatoscopic pattern of CCA resembles that of psoriasis after the scales are removed. [44],[45],[46] Zalaudek and Argenziano reported that differentiation between CCA and psoriasis is made possible by evaluating the distribution pattern of vessels. Dermatoscopy of CCA reveals the linear pearl-like vessels as pearls in a line, which can be distinguished clearly from the dotted vessels in psoriasis. [47]

Vascular lesions

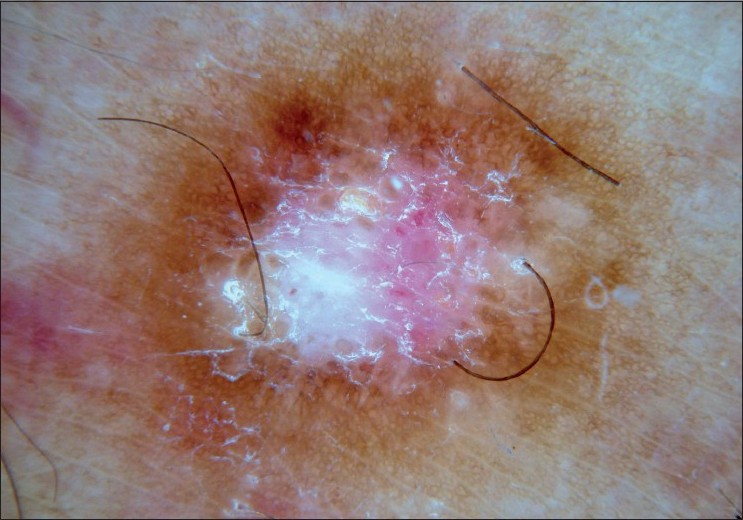

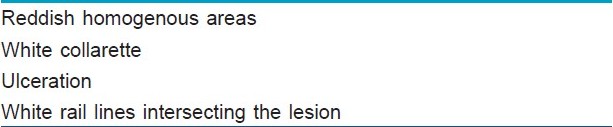

Dermoscopy improves the diagnostic accuracy in the clinical evaluation of pigmented skin lesions, but it is also useful for the assessment of vascular lesions such as hemangioma, solitary angiokeratoma, and pyogenic granuloma. [1],[20] The most typical dermatoscopic features of the vascular lesions are red, blue or black lacunae [Figure - 9],[Figure - 10],[Figure - 11] and red-bluish or red-black homogenous areas. Dermatoscopic features of pyogenic granuloma were first studied by Zaballos et al. [Table - 5]. [48]

|

| Figure 9 :Dermatoscopy of hemangioma – red homogeneous area |

|

| Figure 10 :Dermatoscopy of pyogenic granuloma – red lagoons, appearance of white collarette and white "rail lines" that intersect the lesion |

|

| Figure 11 :Dermatoscopy of Kaposi's sarcoma – bluish-red coloration and scaly surface |

Kaposi′s sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal angioproliferative disease characterized by the proliferation of spindle and endothelial cells. The dermatoscopic features of KS are bluish-reddish coloration (seen in the 84% of lesions), "rainbow pattern" (36%), scaly surface and small brown globules (15%). [49] The multicolored rainbow pattern is the most distinctive and diagnostic feature of KS under polarized dermatoscopy and it is associated with the vascular lumen-rich histologic subtype. The rainbow pattern can be rarely seen in melanoma and other skin lesions. [50]

Conclusion

Dermatoscopy is a simple, non-expensive and non-invasive technique that improves the diagnostic accuracy of non-melanocytic skin tumors. It is one of the most developing and investigative fields of dermatology. Dermatologists should be aware of dermatoscopic features of pigmented BCC for its discrimination from melanoma. Non-pigmented BCC sometimes cannot be clinically discriminated from sebaceous hyperplasia and dermatological evaluation of vascular structures is useful in the differential diagnosis. Facial AK that is one of the differential diagnoses of melanoma has a peculiar dermatoscopic pattern. CCA has a similar dermatoscopic appearance to psoriasis but not the same vascular structures. Kaposi′s sarcoma can be easily distinguished from other vascular lesions by means of its particular multicolored pattern. Since novel dermatoscopic patterns and features are always reported for skin lesions, dermatoscopy is a continuously improving technique of dermatology. Thus, every dermatologist should acquire more in-depth knowledge relating to the dermatoscopic features and patterns of the benign and malignant skin lesions.

| 1. |

Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, Di Stefani A, Ferrara G, Marghoob AA, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Dermoscopy in general dermatology. Dermatology 2006;212:7-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Paschoal FM. Early diagnosis of melanoma by surface microscopy (dermatoscopy). Sao Paulo Med J 1996;114:1220-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Vossaert KA. Malignant melanoma in the 1990s: The continued importance of early detection and the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin. CA Cancer J Clin 1991;41:201-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Piccolo D, Smolle J, Argenziano G, Wolf IH, Braun R, Cerroni L, et al. Teledermoscopy--results of a multicentre study on 43 pigmented skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare 2000;6:132-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Soyer HP, Kenet RO, Wolf IH, Kenet BJ, Cerroni L. Clinicopathological correlation of pigmented skin lesions using dermoscopy. Eur J Dermatol 2000;10:22-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Nilles M, Boedeker RH, Schill WB. Surface microscopy of naevi and melanomas--clues to melanoma. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:349-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Soyer HP, Smolle J, Hodl S, Pachernegg H, Kerl H. Surface microscopy. A new approach to the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Am J Dermatopathol 1989;11:1-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Steiner A, Pehamberger H, Binder M, Wolff K. Pigmented Spitz nevi: Improvement of the diagnostic accuracy by epiluminescence microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:697-701.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Steiner A, Pehamberger H, Wolff K. Improvement of the diagnostic accuracy in pigmented skin lesions by epiluminescent light microscopy. Anticancer Res 1987;7:433-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Demirtasoglu M, Ilknur T, Lebe B, Kusku E, Akarsu S, Ozkan S. Evaluation of dermoscopic and histopathologic features and their correlations in pigmented basal cell carcinomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:916-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Steiner A, Pehamberger H, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. II. Diagnosis of small pigmented skin lesions and early detection of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:584-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. I. Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:571-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Cabrijan L, Lipozencic J, Batinac T, Lenkovic M, Gruber F, Stanic Zgombic Z. Correlation between clinical-dermatoscopic and histopathologic diagnosis of skin tumors in our patients. Coll Antropol 2008;32:195-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Tabanlioglu Onan D, Sahin S, Gokoz O, Erkin G, Cakir B, Elcin G, et al. Correlation between the dermatoscopic and histopathological features of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010 [In Press].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Warshaw EM, Lederle FA, Grill JP, Gravely AA, Bangerter AK, Fortier LA, et al. Accuracy of teledermatology for nonpigmented neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:579-88.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ 2003;327:794-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Brooke RC. Basal cell carcinoma. Clin Med 2005;5:551-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Felder S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, Kopf A. Dermoscopic differentiation of a superficial basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Dermatol Surg 2006;32:423-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:268-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Kreusch JF. Vascular patterns in skin tumors. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:248-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Menzies SW, Westerhoff K, Rabinovitz H, Kopf AW, McCarthy WH, Katz B. Surface microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:1012-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Terstappen K, Larko O, Wennberg AM. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma--comparing the diagnostic methods of SIAscopy and dermoscopy. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:238-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Kettler AH, Goldberg LH. Seborrheic keratoses. Am Fam Physician 1986;34:147-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Cashmore RW, Perry HO. Differentiating seborrheic keratosis from skin neoplasm. Geriatrics 1985;40:69-71, 4-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Braun RP, Rabinovitz HS, Krischer J, Kreusch J, Oliviero M, Naldi L, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis: A morphological study. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1556-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, Kopf AW, Saurat JH. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:270-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Sahin MT, Ozturkcan S, Ermertcan AT, Gunes AT. A comparison of dermoscopic features among lentigo senilis/initial seborrheic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma on the face. J Dermatol 2004;31:884-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Callen JP, Bickers DR, Moy RL. Actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:650-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Rossi R, Mori M, Lotti T. Actinic keratosis. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:895-904.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Schwartz RA, Bridges TM, Butani AK, Ehrlich A. Actinic keratosis: An occupational and environmental disorder. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:606-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Piaserico S, Belloni Fortina A, Rigotti P, Rossi B, Baldan N, Alaibac M, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2007;39:1847-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Dinehart SM. The treatment of actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:25-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Zalaudek I, Giacomel J, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Micantonio T, Di Stefani A, et al. Dermoscopy of facial nonpigmented actinic keratosis. Br J Dermatol 2006;155:951-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Arpaia N, Cassano N, Vena GA. Dermoscopic patterns of dermatofibroma. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:1336-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Zaballos P, Puig S, Llambrich A, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of dermatofibromas: A prospective morphological study of 412 cases. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:75-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Boonchai W, Leenutaphong V. Familial presenile sebaceous gland hyperplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:120-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Zouboulis CC, Boschnakow A. Chronological ageing and photoageing of the human sebaceous gland. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001;26:600-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Cerio R, Spaull J, Jones EW. Histiocytoma cutis: A tumour of dermal dendrocytes (dermal dendrocytoma). Br J Dermatol 1989;120:197-206.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Hui P, Glusac EJ, Sinard JH, Perkins AS. Clonal analysis of cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). J Cutan Pathol 2002;29:385-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Zelger B. Pigmented atypical fibroxanthoma, a dermatofibroma variant? Am J Dermatopathol 2004;26:84-6; author reply 6-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Zelger B, Zelger BG, Burgdorf WH. Dermatofibroma: A critical evaluation. Int J Surg Pathol 2004;12:333-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Bugatti L, Filosa G, De Angelis R. The specific dermoscopical criteria of Bowen's disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:700-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

de Giorgi V, Alfaioli B, Papi F, Janowska A, Grazzini M, Lotti T, et al. Dermoscopy in pigmented squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg 2009;13:326-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Akin FY, Ertam I, Ceylan C, Kazandi A, Ozdemir F. Clear cell acanthoma: New observations on dermatoscopy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:285-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Blum A, Metzler G, Bauer J, Rassner G, Garbe C. The dermatoscopic pattern of clear-cell acanthoma resembles psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 2001;203:50-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Bugatti L, Filosa G, Broganelli P, Tomasini C. Psoriasis-like dermoscopic pattern of clear cell acanthoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003;17:452-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Zalaudek I, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Argenziano G. Dermoscopy of clear-cell acanthoma differs from dermoscopy of psoriasis. Dermatology 2003;207:428; author reply 429.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Zaballos P, Llambrich A, Cuellar F, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopic findings in pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:1108-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Hu SC, Ke CL, Lee CH, Wu CS, Chen GS, Cheng ST. Dermoscopy of Kaposi's sarcoma: Areas exhibiting the multicoloured 'rainbow pattern'. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:1128-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Cheng ST, Ke CL, Lee CH, Wu CS, Chen GS, Hu SC. Rainbow pattern in Kaposi's sarcoma under polarized dermoscopy: A dermoscopic pathological study. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:801-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

10,121

PDF downloads

5,802