Translate this page into:

Dermoscopy aiding diagnosis of nodular granulomatous secondary syphilis

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Das P, Singh GK, Cheema S, Sapra D, Das NK, Mukhida SS. Dermoscopy aiding diagnosis of nodular granulomatous secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_198_2023.

Dear Editor

Syphilis is an ancient yet a relevant contemporary disease because of its increasing incidence in recent years. The causative organism Treponema pallidum, a spirochete, is sexually transmitted. The inoculation of the organism into the body causes the classic, painless chance of primary syphilis. Since it is painless, it is often overlooked. Consequently, the disease progresses into a secondary stage characterised by a rash associated with systemic symptoms like fever, body ache, malaise, headache, and joint pains. The rash is usually maculopapular and resolves in a few weeks. The rash is rarely nodular in secondary syphilis.

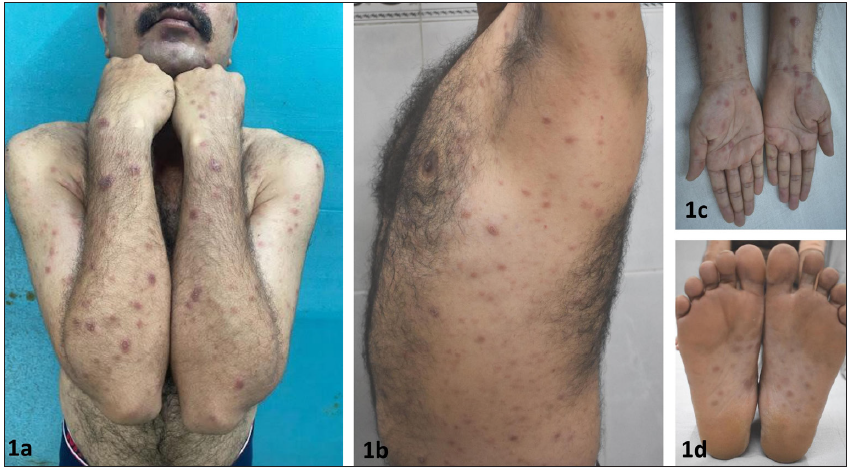

A 38-year-old sexually active male presented with asymptomatic nodules over the body associated with a fever of 3 weeks’ duration. The fever was intermittent and was of moderate grade. There was a history of a painless ulcer over the glans penis 3 weeks ago which healed on its own. On further probing, there was a history of multiple episodes of unprotected sexual exposure with commercial sex workers the last being approximately 2 months ago. Clinical examination revealed a mildly tender and enlarged cervical, axillary, and inguinal group of lymph nodes. Dermatological examination revealed discrete nodules distributed over the face, neck, trunk, gluteal area, and extremities including palms and soles in the form of erythematous to hyperpigmented nodules [Figures 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d]. The Buschke Ollendorf’s sign was positive. Most of the nodules showed scales arranged in linear configuration suggestive of Biett’s collarette which was visible to the naked eye and was reconfirmed with dermoscopy [Figure 2]. Detailed neurological, cardiovascular, ocular, and oto-rhino-laryngological examination was within normal limits. Investigations revealed positive VDRL (titre 1:128) as well as TPHA tests (titer 1:1280). Further testing also revealed HIV-1 positivity by RAPID as well as Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). CD4 count was 346 cells per mm.3 Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) examination was normal. A detailed workup for any other opportunistic infections did not yield any positive results. Skin biopsy from one of the nodules showed well-formed epithelioid granulomas in both superficial as well as deep dermis concentrated especially around the vessels and appendages. Plasma cells were conspicuously absent [Figure 3]. He was diagnosed as a case of nodular variant of secondary syphilis, co-infected with HIV. He was administered a single dose of injection benzathine penicillin intramuscularly at 2.4 million units. He was also started on antiretroviral therapy once daily cotrimoxazole DS (trimethoprim 160 mg and sulfamethaxazole 800 mg). All the nodular lesions resolved in a fortnight leaving behind post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

- Nodular rash distributed over face, neck, trunk and extremities including palms and soles.

- Collarette of scales visible to the naked eye was confirmed on dermoscopy which showed scales arranged in linear configuration which was suggestive of Biett’s collarette. (Polarised, contact, x10).

- Skin biopsy from a nodule scanner view shows inflammatory infiltrates in superficial as well as deep dermis. The infiltrates are arranged mainly around the vessels and appendages (Haematoxylin & Eosin, x40). Higher magnification reveals the infiltrate to be well formed granulomas concentrated around the vessels and appendages (Hematoxylin and Eosin; 200x)

Secondary syphilis usually presents with a generalised papulosquamous rash with systemic flu-like symptoms. However, atypical presentations like macular, papular/nodular, pustular, ulcerative, annular, lichenoid lesions like morphology with or without systemic symptoms have been reported with corresponding histopathologic patterns.1 The lesions typically appear over the trunk, extremities, and head. Involvement of palms and soles is characteristic of secondary syphilis. Granulomatous inflammation is usually a manifestation of tertiary syphilis, not secondary. Nevertheless, less than 50 cases of granulomatous secondary syphilis have been reported to date.2 Nodular syphilis has been especially reported in co-infection with HIV as seen in our case.3–5 Biett’s collarette has been characteristically described in the macula-papular rash of secondary syphilis. It presents as a continuous collarette of scales arranged in a circular configuration which is surrounded by a halo of erythema or hyper-pigmentation on the lesions of secondary syphilis. Dermoscopy is a useful tool in differentiating Biett’s collarette from other papulosquamous conditions like pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, erythema annulare centrifugum, erythema multiforme, actinic porokeratosis, discoid lupus erythematosus, granuloma annulare, rash of reactive arthritis, etc. Annular lesions of actinic porokeratosis show a thicker, irregular collarette than that of Biett’s collarette of secondary syphilis. Dermoscopy reveals uneven, rough scales attached at internal and peripheral borders of the scaling edge, indicating peeling directed both inwards and outwards. Erythema annulare centrifugum shows a homogeneous collarette of scaling which on dermoscopy reveals fine, fragile scaling with irregular edges. A dermoscopy of pityriasis rosea reveals fine, multiple fragments of scales without any defined direction. Dermoscopy of discoid lupus erythematosus highlights diffuse pink areas with arborising vessels and irregular scales with no specific direction of peeling. Dermoscopy of granuloma annulare shows a non-specific diffuse scaling pattern over both the periphery and centre of the lesion with arborising vessels homogeneously distributed all over the slightly elevated border. A nodular morphology of secondary syphilis may not always correspond to granulomatous histopathology. The granulomatous inflammation has been reported to be predominantly perivascular and periadnexal in distribution as demonstrated in our case.2 Two studies have reported rare or absent plasma cells in a quarter and a third of patients with secondary syphilis lesions, though these findings were not limited to cases with a granulomatous pattern.6,7 Our case had a noticeable absence of plasma cells contrary to the typical histopathological finding in classical papulosquamous rash of secondary syphilis. We present the case for its rarity and at the same time stress the utility of dermoscopy in diagnosing a case of secondary syphilis.

Declaration of patient consent

They authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- The great imitator revisited: The spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodular secondary syphilis with associated granulomatous inflammation: Case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:370-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Nodular secondary syphilis in a HIV patient mimicking cutaneous lymphoma] An Med Interna Madr Spain 1984. 2004;21:241-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pruritic nodular secondary syphilis in a 61-year-old man with HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:732-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodular secondary syphilis in three HIV-positive patients: A case series. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31:1004-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secondary syphilis: A clinico-pathological review. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:53-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secondary syphilis. Clinical morphology and histopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:11-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]