Translate this page into:

Development and validation of a Hindi language health-related quality of life questionnaire for melasma in Indian patients

2 Department of Dermatology, Army College of Medical Sciences, Base Hospital, New Delhi, India

3 Department of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA

4 University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

5 Department of Dermatology, Safdurjung Hospital, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Rashmi Sarkar

Department of Dermatology, Maulana Azad Medical College, Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi

India

| How to cite this article: Sarkar R, Garg S, Dominguez A, Balkrishnan R, Jain R K, Pandya AG. Development and validation of a Hindi language health-related quality of life questionnaire for melasma in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016;82:16-22 |

Abstract

Background: Melasma, which is fairly common in Indians, causes significant emotional and psychological impact. A Hindi instrument would be useful to assess the impact of melasma on the quality of life in Indian patients. Objective: To create a semantic equivalent of the original MELASQOL questionnaire in Hindi and validate it. Methods: A Hindi adaptation of the original MELASQOL (Hi-MELASQOL) was prepared using previously established guidelines. After pre-testing, the Hi-MELASQOL questionnaire was administered to 100 women with melasma visiting the out-patient registration counter of Safdarjung Hospital, Delhi. These women were also administered a Hindi equivalent of the Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) questionnaire. Melasma area severity index (MASI) of all the participants was calculated. Results: The mean MASI score was 20.0 ± 7.5 and Hi-MELASQOL score was 37.19 ± 18.15; both were highly, positively and significantly correlated. Reliability analysis showed satisfactory results. Physical health, emotional well-being and social life were the most adversely affected life domains. Limitations: It was a single-center study and the number of patients studied could have been larger. Conclusion: Hi-MELASQOL is a reliable and validated tool to measure the quality of life in Indians with melasma.Introduction

Melasma, a common disorder of hyperpigmentation, presents with irregular brown or grayish brown macules, usually located on the face and neck.[1] Women and individuals with Fitzpatrick's skin type ranging between IV and VI are more commonly affected and exacerbation often occurs during summer months.[2],[3] It is more commonly seen amongst dark-skinned individuals living in areas with intense ultraviolet (UV) radiations, such as Hispanics, Asians and African Americans.[1],[4],[5],[6] Melasma can negatively affect the quality of life (QOL) of affected patients, with a pronounced impairment of emotional and social life.[7],[8] In 2003, Balkrishnan et al. devised a new instrument called the melasma QOL (MELASQOL) questionnaire, to measure the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients with melasma.[7] Using the MELASQOL, Balkrishnan et al. found that in patients with melasma, social life, emotional well-being, recreation and leisure activities were the most commonly affected domains of quality of life.[7]

The goal of our study was to create and validate a semantic equivalent of the original MELASQOL questionnaire in Hindi (Hi-MELASQOL), the national language of India. We used this Hindi language questionnaire to characterize the effect of melasma in Indian women.

Methods

Preparation of Hi-MELASQOL

Adaptation of the original MELASQOL questionnaire into Hindi was performed by a process that involved translation, committee review, back-translation, review, pre-testing and final revision.

Translation

Four bilingual individuals independently prepared a Hindi translation of the original English MELASQOL questionnaire. The group was instructed to make a semantic equivalent of the original MELASQOL questionnaire and not merely a literal Hindi translation, keeping in mind the education level of the target population (about 12 years of elementary schooling). The Hindi translation was reviewed by a committee which included four of the authors (RS, RB, RKJ, AGP). The resulting finalized Hindi adaptation was then back-translated into English individually by four bilingual non-medical individuals. All the translators were unaware of the underlying concept and intent of the questionnaire. Two of the authors (RS, AGP) reviewed the back-translations. Those questions which were not semantically equivalent to the original questionnaire were re-translated and back-translated again until equivalence was attained.

Pretesting

The final version of the questionnaire was subjected to pretesting in 20 women with melasma who were recruited from the outpatient registration counter for all specialties of Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi. In order to determine the correct interpretation of each question, each patient was asked to justify her answers to the questions and to explain in detail what each question meant to her “in her own words.” If more than 1 patient (>5%) misunderstood the semantic definition of a question or found it difficult to read, it was designated as unreadable.

Final revision

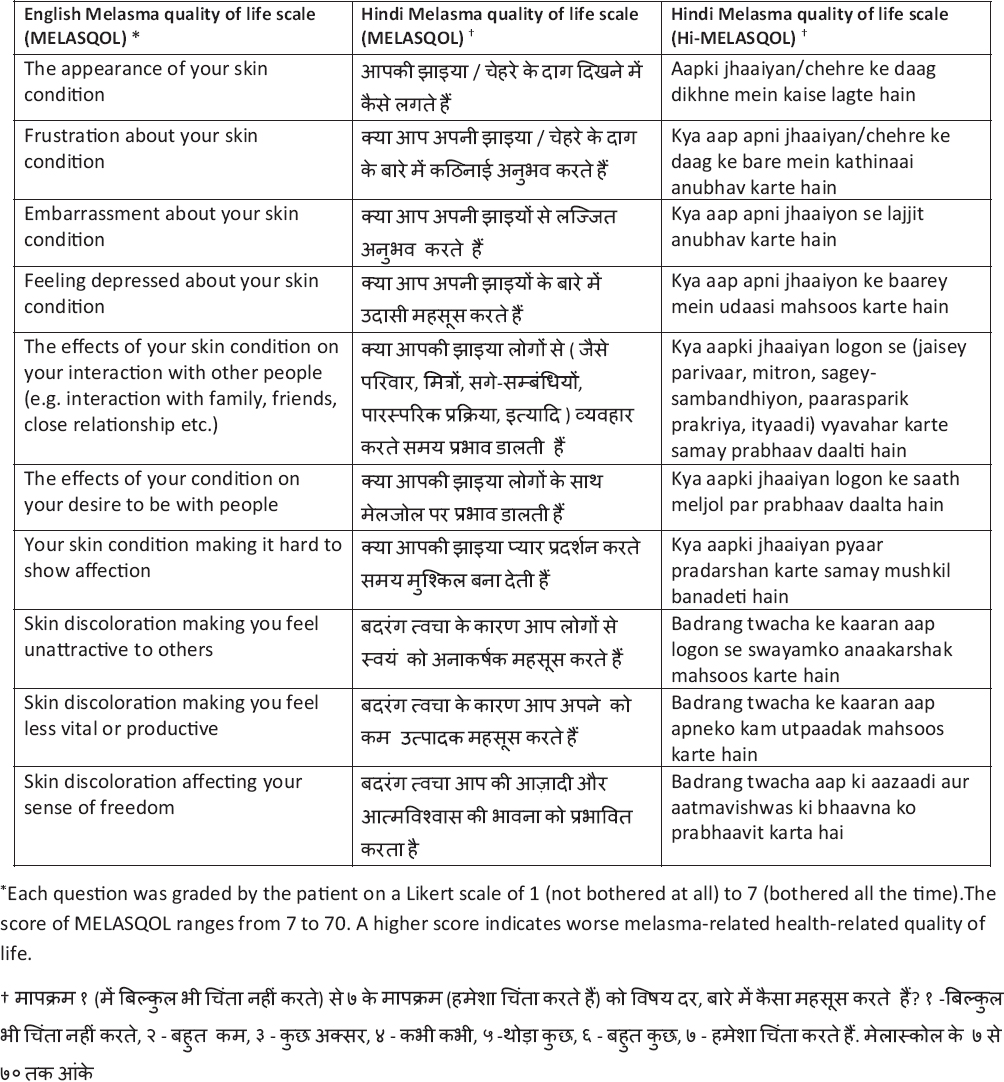

Using the comments and feedback from the pilot study, the unreadable questions were revised and then back-translated. These questions were resubmitted to the authors (RS, AGP) for approval and were then presented again to the patients to ensure they were readable. The original English language MELASQOL questionnaire and its final Hindi language version are given in [Table - 1].

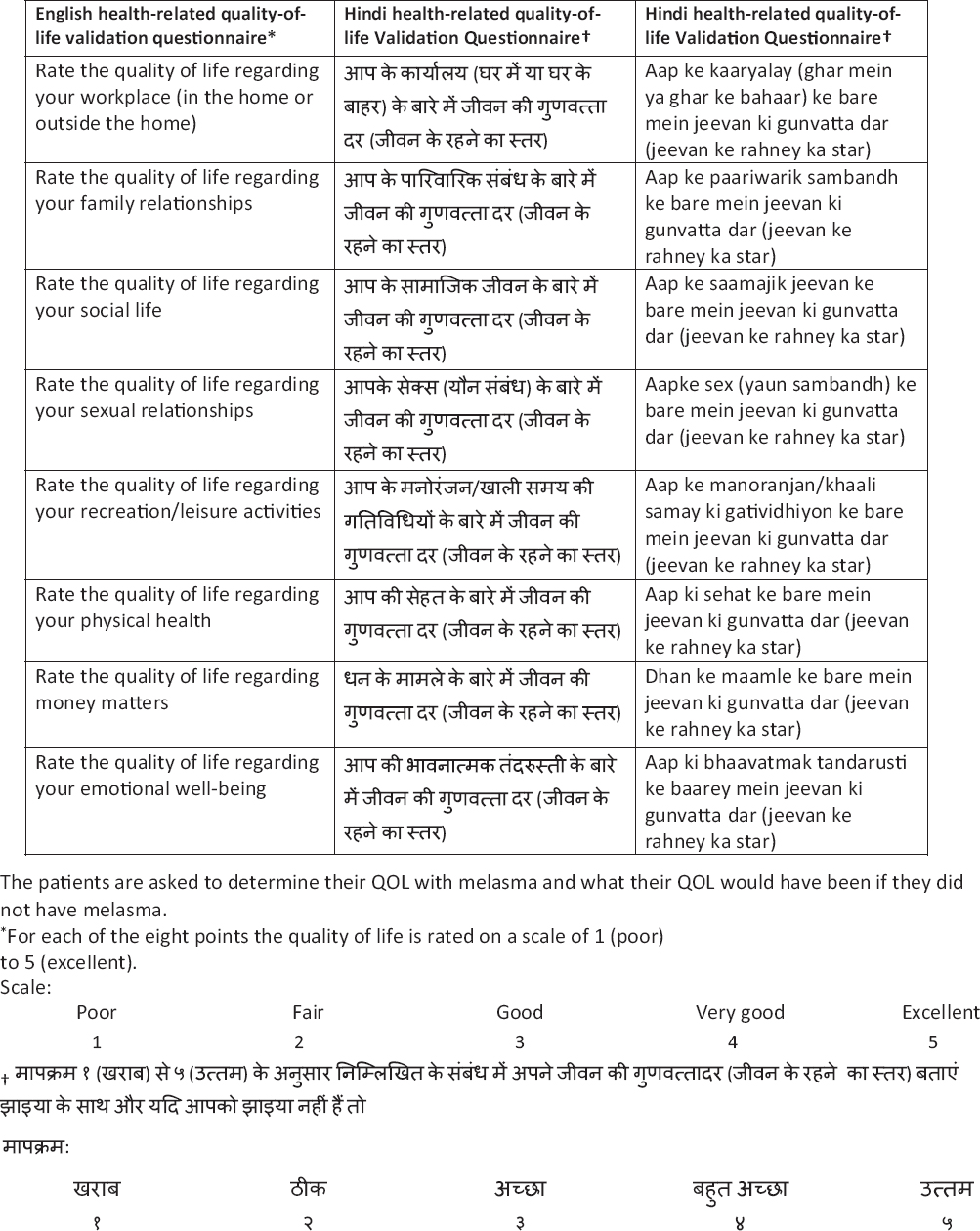

To validate the Hi-MELASQOL questionnaire, a validated HRQOL questionnaire was given to each patient [Table - 2].[7] A similar process involving translation, committee review, back-translation, review, pre-testing and final revision was undertaken to develop the Hindi version of the HRQOL questionnaire [Table - 2].

Administration

Approval for this cross-sectional study was obtained from the institutional review board of Safdarjung Hospital. To validate the questionnaire, 100 patients with melasma were identified and recruited by the investigators from the out-patient registration counter of Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi. Sample size calculation was based on the Spearman's correlation coefficient of 0.35 obtained in the study by Balkrishnan et al.[7] Inclusion criteria for the study were women of Indian origin with melasma who were ≥18 years and <55 years of age and who could understand and read Hindi. Exclusion criteria included current pregnancy or pregnancy within the last 6 months, menopause and history of bilateral oophorectomy. Women who were unwilling or unable to understand the questionnaire were also excluded from the study. After obtaining informed consent from the patients, demographic data, medical history and psychiatric history were recorded. Standardized and validated methods were adopted and objective measures were used in order to avoid information inaccuracies and biases. The severity of melasma in each patient was determined by a dermatologist using the melasma area severity index (MASI), a validated outcome measure for melasma.[9]

Each of the 100 patients were given the Hindi HRQOL and Hi-MELASQOL questionnaires. While filling the Hindi HRQOL questionnaire, they were asked to determine both their quality of life with melasma and also what their quality of life would have been, hypothetically, if they did not have melasma. Construct validity was confirmed by demonstration of high correlation between the Hi-MELASQOL scale and the HRQOL psychosocial domains. The Internal reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Paired t-test was applied to compute Cohen's d effect to measure the impact of melasma while comparing patient scores on HRQOL for “with melasma” and “without melasma”. For all statistical analyses, a P ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference at 5% level of significance. SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed for all quantitative data. Correlation between MASI and Hi-MELASQOL was assessed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to check for any association between disease severity and quality of life. It was also used to test any association of MASI and MELASQOL with age.

Results

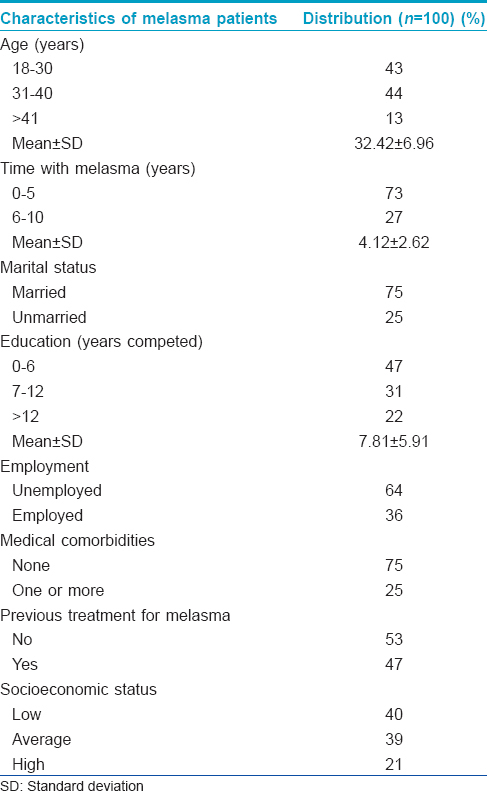

All the 100 recruited patients participated throughout the study. No problematic questions were found in the validation of Hi-MELASQOL and Hindi HRQoL questionnaire due to its simple format. The demographic details of the studied individuals are shown in [Table - 3]. The mean age was 32 years. The average duration of melasma was 4 years. Since there was no further sub-division of subjects based on any other criterion and no use of any other scale except Hi-MELASQOL to measure the QOL, it was a simple one-time survey; there were no adjusted estimates or confounder estimates.

The mean MASI score as assessed by the physician was 20.0 ± 7.5. The Hi-MELASQOL score was 37.19 ± 18.15. The Spearman's correlation between MASI and Hi-MELASQOL was 0.809 which implies they are highly and positively correlated. Also since the P value is < 0.05, we can conclude that the correlation between the two is significant at 5% level of significance.

Reliability analysis showed satisfactory results with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.861. Inter-item correlation (convergent validity) between the eight domains (work, family, social life, sex life, leisure, physical health, money matters and emotional well-being) was positive, ranging from 0.159 to 0.693. This implies there is a direct relation between the domains and that an increase in one variable implies an increase in another variable.

Comparison of Hi-MELASQOL scores with score values obtained for individual domains of the HRQOL showed that the overall score for the Hi-MELASQOL is negatively correlated with all the eight domains, indicating that an increase in the Hi-MELASQOL is associated with a decrease in all eight domains of HRQOL. Moreover, all except one of these correlations was significant (P< 0.05). Only money matters did not correlate significantly with Hi-MELASQOL (P = 0.081). The inverse correlation of Hi-MELASQOL is most significant with social life (P< 0.001) and less significant with leisure (P = 0.002). Spearman's correlation was used as it is a non-parametric measure.

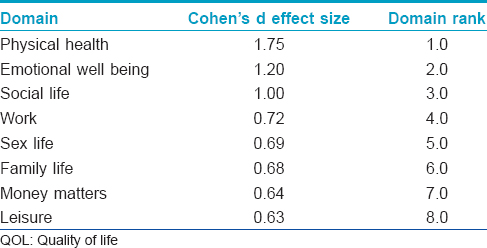

[Table - 4] lists the Cohen's d effect size for the quality of life domains as assessed by HRQOL. A larger Cohen's d effect size denotes a greater perceived improvement by the patient in quality of life if they were actually free from melasma and implies a greater impact of melasma on a particular domain. From this table we conclude that physical health is most likely to be perceived as affected by melasma followed by emotional well-being and social life.

The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between age and Hi-MELASQOL was 0.199 which is significant (P = 0.047), implying that increase in age corresponds to a significant increase in Hi-MELASQOL. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between MASI and age was 0.204 which is also significant (P = 0.041), indicating worsening of melasma with age.

Discussion

It is important to have a disease-specific, dermatologically relevant HRQOL questionnaire for melasma which focusses on its effect on the psyche. Most researchers have found that melasma has a greater impact on the psychological health of the patient as compared to physical health. However our study showed that physical health was most likely to be perceived as affected by melasma. This could be due to less educated patient population in our study who are likely to be misinformed about the disease. In the authors experience, many patients associate melasma with iron deficiency and as a sign of some underlying undiagnosed physical ill health. These beliefs could possibly offer an explanation why our patients reported physical health to be most affected by melasma. This may also point towards an increased need to educate our patients about the etiopathogenesis of melasma.

MELASQOL was first compiled in English and has now been translated and validated in Spanish, French, Brazilian Portuguese, Persian and Turkish.[8],[10],[11],[12],[13]

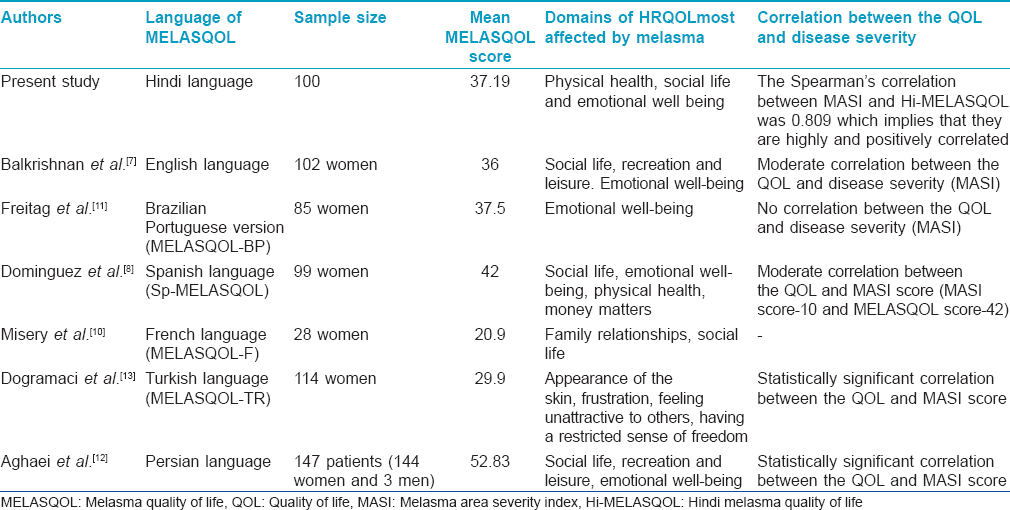

The mean Hi-MELASQOL score in the our study was 37.19. In the study by Freitag et al., Dominguez et al. and Aghaei et al. the mean MELASQOL score was found to be higher (37.5, 42 and 52.85 respectively) score.[8],[11],[12] However, the Hi-MELASQOL score was higher as compared to the MELASQOL score in the study by Balkrishnan et al., Misery et al. and Dogramaci et al. (36, 20.9 and 29.9 respectively).[7],[10],[13] These differences, if significant, could be due to variations in latitude, sun exposure, occupations, culture, skin type or other factors.

The Spearman's correlation between MASI and Hi-MELASQOL was 0.809 which is considered high, indicating that quality of life worsens as melasma becomes more severe. This is in agreement with similar studies performed in most other languages; however, of note, no significant correlation was found in the studies by Balkrishnan et al., Freitag et al. and Dominguez et al.[7], 8, [11],[12],[13]

The reliability analysis showed a satisfactory result with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.861 indicating a high level of internal consistency for the scale. The correlation of the Hi-MELASQOL scale with different HRQOL domains shows a negative correlation with all the domains except money matters. Thus, an increase in Hi-MELASQOL is associated with a decrease in the values of all seven domains. The inverse correlation of Hi-MELASQOL is most significant with social life. Overall, in our study, the three domains of quality of life (as assessed by the Hindi HRQOL questionnaire) most affected by melasma were physical health, social life and emotional well-being.

Our study also found a significant correlation between age and Hi-MELASQOL suggesting that older patients with chronic hyperpigmentation of the face suffer from a worse quality of life due to their condition than younger patients.

The results of our study overall are similar to studies conducted using the MELASQOL questionnaire in various parts of the world in different languages, giving further evidence of the negative impact of melasma, worldwide [Table - 5].[7],[8],[11],[12]

The limitations of the study were that it was a single-center study and that a larger number of patients could have been enrolled in the study.

Conclusion

The Hindi language version of the MELASQOL scale is a reliable and valid tool to assess the health-related quality of life in Hindi-speaking patients with melasma.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the help of Dr. Vaneeta Sheth, Dr. Seema Daulat, Dr. Silonie Sachdeva, Dr. Anupama Tiwari and Dr. Radha Yalamanchili for helping in back-translation of questionnaires and interviewing some patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Pandya AG, Guevara IL. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Clin 2000;18:91-8, ix.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Goh CL, Dlova CN. A retrospective study on the clinical presentation and treatment outcome of melasma in a tertiary dermatological referral centre in Singapore. Singapore Med J 1999;40:455-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Urabe K, Nakayama J, Hori Y. Mixed epidermal and dermal hypermelanosis. In: Nordlund JJ, Boissy RE, Hearing VJ, King RA, Ortonne JP, editors. The Pigmentary System Physiology and Pathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 909-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Grimes PE. Melasma. Etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:1453-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL, Mihm MC Jr. Melasma: A clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;4:698-710.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Taylor SC. Epidemiology of skin diseases in people of color. Cutis 2003;71:271-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Balkrishnan R, McMichael AJ, Camacho FT, Saltzberg F, Housman TS, Grummer S, et al. Development and validation of a health-related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:572-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Dominguez AR, Balkrishnan R, Ellzey AR, Pandya AG. Melasma in Latina patients: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire in Spanish language. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:59-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Pandya AG, Hynan LS, Bhore R, Riley FC, Guevara IL, Grimes P, et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:78-83, 83.e1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Misery L, Schmitt AM, Boussetta S, Rahhali N, Taieb C. Melasma: Measure of the impact on quality of life using the French version of MELASQOL after cross-cultural adaptation. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:331-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Freitag FM, Cestari TF, Leopoldo LR, Paludo P, Boza JC. Effect of melasma on quality of life in a sample of women living in southern Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:655-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Aghaei S, Moradi A, Mazharinia N, Abbasfard Z. The Melasma Quality of Life scale (MELASQOL) in Iranian patients: A reliability and validity study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19 Suppl 2:39

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Dogramaci AC, Havlucu DY, Inandi T, Balkrishnan R. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for the Turkish language: The MelasQoL-TR study. J Dermatolog Treat 2009;20:95-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,107

PDF downloads

2,038