Translate this page into:

Early detection of sensory nerve function impairment in leprosy under field conditions

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: John AS, Govindharaj P. Early detection of sensory nerve function impairment in leprosy under field conditions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:241-6.

Abstract

Aim:

To assess the fine sensation of palms and soles in field conditions, to enable early detection of nerve function impairment before the loss of protective sensation, thus preventing the development of disability.

Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at seven tertiary referral hospitals located in different states in India. This study included all newly diagnosed patients affected by leprosy, who were registered during the period between March 2011 and April 2012. A detailed history was taken along with charting and voluntary muscle testing /sensory testing (VMT/ST) for the diagnosed patients. The sensation was measured using 0.2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 4 gm for soles first, followed by 2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 10 gm for soles.

Results:

Among the 374 patients, 106 were identified with sensory nerve function impairment. Of the 106 patients, 84 were identified with absence of both fine and protective sensation and 22 patients had a loss of fine touch sensation with protective sensation intact.

Limitation:

This study was conducted only among patients who were newly diagnosed with leprosy. Hence, future longitudinal studies in a larger population will add more validity to the study.

Conclusion:

The patients who had loss of fine sensation would have been missed by the normal leprosy programme protocol which uses 2 gm and 10 gm filaments for testing sensory loss before initiating steroid therapy. Further research is needed to determine whether testing for fine sensation with 0.2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 4 gm for soles can be introduced at all specialized leprosy centres to detect nerve function impairment at an earlier stage followed by steroid therapy.

Keywords

Leprosy

sensory testing

nerve function impairment

disability

Semmes-Weinstein filament

Plain Language Summary

Leprosy is a chronic bacterial infection that attacks the peripheral nerves. This may cause nerve function impairment, which, if not detected early and addressed effectively, leads to serious medical and social problems in the affected person. In the leprosy programme, sensory testing is done using 2 gm Semmes-Weinstein monofilament for palms and 10 gm for soles, which detect protective sensation but not fine sensation. The fine sensations are lost long before the loss of protective sensation in the palms and soles. This Indian study was carried out in seven tertiary referral hospitals for leprosy and aimed to detect sensory nerve function impairments early by using 0.2 gm and 4 gm Semmes-Weinstein monofilament in field conditions, thus preventing the development of disability. In total, 374 newly diagnosed leprosy patients were included. Of the 374 patients, 84 (22.5%) had lost both fine and protective sensation and 22 (5.9%) patients had a loss of fine touch sensation with protective sensation intact. This study shows that the patients who had lost fine sensation would have been missed in the normal leprosy programme protocol which uses 2 gm and 10 gm filaments for testing sensory loss before initiating steroid therapy.

Introduction

Preventing permanent disabilities due to nerve function impairment remains a major concern in leprosy control.1 Mycobacterium leprae, the causative agent of leprosy, infiltrates Schwann cells of peripheral nerve fibres.2 Subsequently, the nerve fibres can be damaged by the accumulation of bacteria and hypersensitivity reactions of the immune system. The decline of nerve function can take place before, during and/or after leprosy treatment. Early detection (within six months) and corticosteroid treatment may prevent further decline.3 Nerve Function Impairment distinguishes leprosy from other diseases in several ways: it is insidious, often painless, generally neglected by the affected person and his/her family, progressive if not treated, and results in irreversible nerve damage. Motor and sensory nerve function impairment are still the worst complications of leprosy,3 and if not detected early, and addressed effectively, lead to serious medical and social problems in the affected person.

Several studies,4 mostly operational, and undertaken mainly to manage complications, have been done but the problem of early nerve function impairment in leprosy and its association with various social, clinical and epidemiological parameters, has not been thoroughly investigated and needs further research.5 Thus, we are forced to use clinical experience and available tools astutely and effectively in field conditions for early detection of nerve function impairment, without recourse to expensive/ hi-tech laboratory tests. This necessitates studies to devise ways of assessing the risk of nerve function impairment and prevent it, by developing specific diagnostic tools for field application.6

In the leprosy programme, sensory testing is mostly done using 2 gm monofilament for palms and 10 gm for soles, which detects protective sensation but not fine sensation. The fine sensations are lost long before the loss of protective sensation in the palms and soles. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the deterioration of fine sensation of palms and soles before the loss of protective sensation and to assess the suitability of fine touch testing Semmes-Weinstein filaments for field application. This will detect nerve function impairment early and prevent the development of disability.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at seven tertiary referral hospitals for leprosy disease in India at Shahdra (Delhi), Purulia (West Bengal), Barabanki (Uttar Pradesh), Naini (Uttar Pradesh), Kothara (Maharastra) and Chandkuri (Chaatisgarah). Persons reporting for the first time for diagnosis and treatment, registered in the referral hospital were included after taking consent. Totally, 374 patients were included in this study from March 2011 to April 2012.

Procedure

Initially, an orientation programme was conducted for the physiotherapists from the participating centres to ensure uniformity. Each patient had a detailed history taken along with body charting, voluntary muscle testing and sensory testing. After the registration, participants underwent nerve function impairment assessment which was recorded along with the routine sensory and motor nerve function testing.

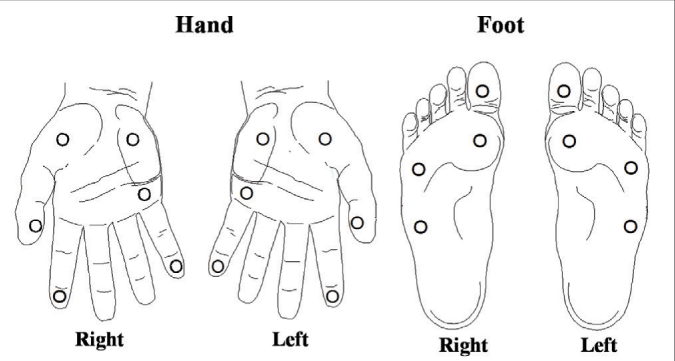

Sensory testing: Sensation was measured using 0.2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 4 gm for soles first for testing the fine sensation, followed by 2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 10 gm for soles for testing the protective sensation. On each hand, three points on the ulnar nerve and three points on the median nerve were tested. On each foot, four points in the area of the posterior tibial nerve were tested [Figure 1].7

- Monofilament test sites in hand and foot

The sensory score for each point: For each site, the presence of sensation was scored ‘1’ and the absence of sensation was scored ‘0’. The scores ranged 0–3 for ulnar nerve site of palm, 0–3 for median nerve site of palm and 0–4 for posterior tibial nerve site of sole for each testing of fine and protective sensation.

Motor testing: Muscle strength was tested with the modified Medical Research Council scale (0–5). The muscles strength was categorized as normal (Medical Research Council grade, 5 & 4), impaired (Medical Research Council grade, 3, 2 & 1) and paralysis (Medical Research Council grade, 0). Muscles innervated by the facial, ulnar, median, radial, and lateral popliteal nerves were assessed by asking the participant to perform five movements: eye closure, little finger abduction, thumb abduction, wrist extension, and ankle dorsiflexion.8

Ethical clearance was obtained from Research Ethical Committee of The Leprosy Mission Trust India, New Delhi and written consent from the participants was obtained. The collected individual data were entered and analysed in Microsoft database excel sheets (Microsoft Office Excel 2007).

Results

Among the 374 patients, 141 (37.7%) were females (32 children) and 233 (62.3%) were males (35 children) with an age range of 9 to 74 years. Of these, 247 (66%) were between 15 and 45 years. One-hundred and nine (29.2%) were working as manual labourers/farmers, 94 (25.1%) were students and 83 (22.2%) were housewives. Two-hundred and seventy-one (72.5%) were either illiterate or had only primary education [Table 1].

| Status | Frequency | Percentage | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 233 | 62.3 | 0.572–0.672 |

| Female | 141 | 37.7 | 0.328–0.428 |

| Age | |||

| Below 15 | 67 | 17.9 | 0.142–0.223 |

| 15 to 30 | 150 | 40.1 | 0.351–0.453 |

| 31 to 45 | 97 | 25.9 | 0.216–0.307 |

| 46 to 60 | 36 | 9.6 | 0.068–0.131 |

| Above 60 | 24 | 6.4 | 0.042–0.094 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 204 | 54.6 | 0.494–0.597 |

| Single | 162 | 43.3 | 0.382–0.485 |

| Widow and separated | 8 | 2.2 | 0.009–0.042 |

| Occupation | |||

| Manual labourer/farmer | 109 | 29.2 | 0.246–0.340 |

| Skilled labour | 46 | 12.3 | 0.092–0.161 |

| Clerical worker/ professional | 11 | 2.9 | 0.015–0.052 |

| Housewife | 83 | 22.2 | 0.181–0.268 |

| Student | 94 | 25.1 | 0.208–0.299 |

| Not working | 31 | 8.3 | 0.057–0.116 |

| Education | |||

| Primary | 132 | 35.3 | 0.305–0.404 |

| Secondary | 84 | 22.5 | 0.183–0.270 |

| Graduate or higher | 19 | 5.1 | 0.031–0.079 |

| Illiterate | 139 | 37.2 | 0.323–0.423 |

At the time of reporting, 34 (9%) had grade 1 disability and 53 (14%) had grade 2 disability. The bacterial index was positive in 61 (16%) patients, with 37 (10%) having a bacterial index above two. One-hundred and twenty six (34%) were prescribed steroids along with multi-drug therapy at the first visit. The main cause (58%) for the delay in presentation was ignorance of the early signs of leprosy [Table 2].

| Status | Frequency | Percentage | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Index | |||

| Negative | 313 | 83.7 | 0.796–0.873 |

| 0.1–2 | 24 | 6.4 | 0.042–0.094 |

| 2.1–4 | 20 | 5.4 | 0.033–0.081 |

| Above 4 | 17 | 4.6 | 0.027–0.072 |

| RJ classification | |||

| Tuberculoid | 268 | 71.7 | 0.668–0.762 |

| Boderline tuberculoid | 64 | 17.1 | 0.134–0.213 |

| Borderline borderline | 9 | 2.4 | 0.011–0.045 |

| Borderline lepromatous | 10 | 2.7 | 0.013– 0.049 |

| Lepromatous leprosy | 23 | 6.2 | 0.040– 0.091 |

| WHO disability grade | |||

| Grade 0 | 287 | 76.7 | 0.721–0.809 |

| Grade 1 | 34 | 9.1 | 0.064–0.125 |

| Grade 2 | 53 | 14.2 | 0.108–0.181 |

| EHF score | |||

| Score 0 | 287 | 76.7 | 0.721–0.809 |

| Score 1 | 21 | 5.6 | 0.035–0.085 |

| Score 2 | 35 | 9.4 | 0.066–0.128 |

| Score 3 and above | 31 | 8.3 | 0.057–0.116 |

| Treatment given at enroll | |||

| Multi-drug therapy | 248 | 66.3 | 0.613–0.711 |

| Multi-drug therapy& Steroids | 126 | 33.7 | 0.289–0.387 |

About 28 (7.5%) of the participants had right ulnar nerve impairment; of these, 15 (4%) had paralysis. In the left ulnar nerve, 33 (8.8%) had impairment, of which 17 (4.5%) had paralysis. In the median nerve, about nine (2.4%) of the participants had impairment in the right nerve and six (1.6%) in the left nerve. Very minimal level of impairment was present in the facial and lateral popliteal nerve on both sides. There was no impairment in the radial nerve [Table 3].

| Muscle Power | Right Side | Left Side | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial | Ulnar | Median | Radial | Lat.Pop | Facial | Ulnar | Median | Radial | Lat.Pop | |

| Normal | 373 (99.7%) |

346 (92.5%) |

365 (97.6%) |

374 (100%) |

371 (99.2%) |

374 (100%) |

341 (91.2%) |

368 (98.4%) |

374 (100%) |

372 (99.5%) |

| Impaired | 1 (0.3%) |

13 (3.5%) |

7 (1.9%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

16 (4.3%) |

4 (1.1%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.3%) |

| Paralysed | 0 (0%) |

15 (4.0%) |

2 (0.5%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (0.8%) |

0 (0%) |

17 (4.5%) |

2 (0.5%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.3%) |

The results of the sensory assessment of the participants is shown in Table 4. Out of the 374 patients included in the study, 106 (28.4%) had sensory nerve function impairment, of which 84 (79.2%) had lost both fine and protective sensation and 22 (20.8%) patients had a loss of fine touch sensation with protective sensation intact. The sites wise sensory assessment is shown in Table 5.

| Number of nerve affected | Frequency | Percentage | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| No nerves | 268 | 71.7% | 0.668–0.762 |

| 1 nerve | 40 | 10.7% | 0.078–0.143 |

| 2 nerves | 32 | 8.6% | 0.09–0.119 |

| 3 nerves | 11 | 2.9% | 0.015–0.052 |

| 4 nerves | 10 | 2.7% | 0.013–0.049 |

| 5 nerves | 0 | 0.0% | – |

| 6 nerves | 13 | 3.5% | 0.019–0.059 |

| Absent fine Sensation & present protective sensation |

Absent both fine & protective Sensation |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Present both fine & protective sensation |

1 site loss |

2 sites loss |

3 sites loss |

4 sites loss |

1 site loss |

2 sites loss |

3 sites loss |

4 sites loss |

|||||||||

| Ulnar Nerve | ||||||||||||||||||

| Right | 322 | 86.1% | 3 | 0.8% | 9 | 2.4% | 7 | 1.9% | – | – | 2 | 0.5% | 5 | 1.3% | 26 | 7.0% | – | – |

| Left | 322 | 86.1% | 2 | 0.5% | 6 | 1.6% | 9 | 2.4% | – | – | 6 | 1.6% | 7 | 1.9% | 22 | 5.9% | – | – |

| Median Nerve | ||||||||||||||||||

| Right | 338 | 90.4% | 8 | 2.1% | 4 | 1.1% | 5 | 1.3% | – | – | 7 | 1.9% | 3 | 0.8% | 9 | 2.4% | – | – |

| Left | 338 | 90.4% | 6 | 1.6% | 7 | 1.9% | 2 | 0.5% | – | – | 11 | 2.9% | 4 | 1.1% | 6 | 1.6% | – | – |

| Posterior Tibial Nerve | ||||||||||||||||||

| Right | 330 | 88.2% | 8 | 2.1% | 4 | 1.1% | 1 | 0.3% | 3 | 0.8% | 4 | 1.1% | 2 | 0.5% | 2 | 0.5% | 20 | 5.3% |

| Left | 336 | 89.8% | 4 | 1.1% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.1% | 6 | 1.6% | 2 | 0.5% | 3 | 0.8% | 18 | 4.8% |

Among the sensory impairment of the 79 (21.1%) male patients, 18 (22.8%) had a fine sensory loss and intact protective sensation while it was similarly detected in four (14.8%) female patients. Of the 106 patients with sensory impairment, nine (8.5%) were aged below 15 years and two (1.9%) had a fine sensory loss. About 59 (55.6%) of the participants reported within six months after noticing the first symptoms; of these, 12 (20.3%) had fine sensory loss [Table 6].

| Status | Absent fine Sensation &present protective sensation | Absent both fine &protective Sensation | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=22 | N=84 | N=106 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 18 | 4.8% | 61 | 16.3% | 79 | 21.1% |

| Female | 4 | 1.1% | 23 | 6.1% | 27 | 7.2% |

| Age | ||||||

| Below 15 | 2 | 0.5% | 7 | 1.9% | 9 | 2.4% |

| 15 - 30 | 11 | 2.9% | 36 | 9.6% | 47 | 12.6% |

| 31 - 45 | 7 | 1.9% | 17 | 4.5% | 24 | 6.4% |

| 46 - 60 | 2 | 0.5% | 16 | 4.3% | 18 | 4.8% |

| Above 60 | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 2.1% | 8 | 2.1% |

| Duration of delay after noticing the first symptoms |

||||||

| Below 6 month | 12 | 3.2% | 47 | 12.6% | 59 | 15.8% |

| Above 6 month | 10 | 2.7% | 37 | 9.9% | 47 | 12.6% |

Percentage: Denominator (n= 374)

Among the 22 fine sensory loss patients, 10 (45.5%) of them had lost fine sensation in the right ulnar nerve site of the hand while it was nine (40.5%) in the left hand. In the median nerve sites, Eight (36.4%) had lost fine sensation in the right hand and six (27.3%) in the left hand. In the foot, 10 (45.5%) had lost fine sensation in the right foot due to impairment of posterior tibial nerve while it was seven (31.8%) in the left foot [Table 7].

| Nerve | Loss of fine sensation | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Total | |||||||||||

| Ulnar | |||||||||||||||

| Right | 1 | 0.3% | 7 | 1.9% | 2 | 0.5% | – | – | 10 | 2.7% | |||||

| Left | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 1.3% | 4 | 1.1% | – | – | 9 | 2.4% | |||||

| Median | |||||||||||||||

| Right | 3 | 0.8% | 2 | 0.5% | 3 | 0.8% | – | – | 8 | 2.1% | |||||

| Left | 4 | 1.1% | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | – | – | 6 | 1.6% | |||||

| Posterior Tibial | |||||||||||||||

| Right | 7 | 1.9% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.5% | 10 | 2.7% | |||||

| Left | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.1% | 7 | 1.9% | |||||

Percentage: Denominator (n= 374)

Discussion

Early detection of nerve function impairment improves prognosis and prevents deformity in leprosy, with delay in detection being strongly associated with an increased risk of nerve function impairment at diagnosis.9,10 This study emphasizes the early detection of sensory impairment by assessing the fine sensation to detect changes in nerve function earlier to a clinical nerve damage event, thus preventing functional impairment and disability.

The presence of nerve function impairment at diagnosis has been found to be a strong predictor of the risk of further immunological reactions or episodes of sensory or motor neuropathy,11,12 and delayed reporting increases the risk of nerve impairment. The sensory impairment could be detected earlier by assessing the fine sensation using monofilament (0.2 gm for palms and 4 gm for soles) to prevent impairment and deformity, since the fine sensations will be lost before protective sensation. In this study, among the patients with sensory impairment, 22 (21%) had a loss of fine sensation, with intact protective sensation. These patients would have been missed in the normal leprosy programme protocol which uses 2 gm and 10 gm filaments for testing sensory loss, before initiating steroid therapy.

Testing the fine sensation by monofilaments is a cost-effective method to detect nerve function impairment at an earlier stage for initiation of early treatment and could be followed at all specialized leprosy centres and field level programmes. We believe that this method of assessment is very effective in endemic areas, especially in India, since it has the highest number of new cases reported every year, with five percent of them reported with grade 2 disability at the time of diagnosis.

The limitation of the study is that it was conducted only among patients who were newly diagnosed with leprosy. Hence, future longitudinal studies in a larger population will add more validity to the study.

Conclusion

This study shows that the patients who had lost fine sensation would have been missed in the normal leprosy programme protocol which uses 2 gm and 10 gm filaments for testing sensory loss before initiating steroid therapy, Further research is needed to determine whether testing for fine sensation with 0.2 gm Semmes-Weinstein filaments for palms and 4 gm for soles can be introduced at all specialized leprosy centres to detect nerve function impairment at an earlier stage, followed by steroid therapy.

Acknowledgement

The authors express sincere thanks to all participated institutes and physiotherapists who were involved in data collection. This study was fully supported by The Leprosy Mission Trust India, Research Domain. We extend our sincere thanks to Dr PSS Sundar Rao for his guidance and support during the study period. We thank Dr. Joydeepa Darlong, Head- Knowledge and Management, The Leprosy Mission Trust India, New Delhi for her support for this study. We thank all the respondents who participated in this study.

Declaration of patients consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported and sponsored by The Leprosy Mission Trust India, Research Domain.

References

- International classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steroid prophylaxis for prevention of nerve function impairment in leprosy: Randomised placebo controlled trial (TRIPOD 1) BMJ. 2004;328:1459.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Early diagnosis of neuropathy in leprosy-comparing diagnostic tests in a large prospective study (the INFIR cohort study) PLoSNegl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Report on Leprosy- TDR/SWG/02 World Health Organization 2002. Available in: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/68576/1/TDR_SWG_02.pdf (Accessed on 11 December, 2017)

- [Google Scholar]

- Leprosy research and training during the post-elimination phases-scope in India. Health Administrator. 2006;18:60-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential action to minimise disability in leprosy patients. Leprosy Mission International.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basic nerve function assessment in leprosy patients. Lepr Rev. 1981;52:161-70.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Delay in presentation, an indicator for nerve function status at registration and for treatment outcome-the experience of the bangladesh acute nerve damage study cohort. Lepr Rev. 2003;74:349-56.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between detection delay and impairment in leprosy control: A comparison of patient cohorts from Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Lepr Rev. 2006;77:356-65.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence rates of acute nerve function impairment in leprosy: A prospective cohort analysis after 24 months (the Bangladesh acute nerve damage study) Lepr Rev. 2000;71:18-33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The pattern of leprosy-related neuropathy in the AMFES patients in Ethiopia: Definitions, incidence, risk factors and outcome. Lepr Rev. 2000;71:285-308.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]