Translate this page into:

Erythroderma: A clinicopathological study of 370 cases from a tertiary care center in Kerala

Correspondence Address:

Rani Mathew

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government T D Medical College, Alappuzha, Kerala

India

| How to cite this article: Mathew R, Sreedevan V. Erythroderma: A clinicopathological study of 370 cases from a tertiary care center in Kerala. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:625 |

Sir,

Erythroderma or exfoliative dermatitis is an inflammatory disorder in which erythema and scaling occur in a generalized distribution involving more than 90% of the body surface.[1] We conducted a retrospective study to delineate the clinical features and etiological pattern of erythroderma and to note its clinicopathological correlation. Case records of 370 erythroderma patients who attended the Department of Dermatology, Government T D Medical College, Alappuzha, Kerala, during the past 10 years (April 2005–March 2015) were analyzed to study the clinical, laboratory and histopathological data.

Mean age of onset of erythroderma was 55.38 ± 16.67 (range 3-91 years) years. Majority of the patients belonged to the age group of 60–69 years (n = 119, 32%) followed by 50–59 years (n = 81, 22%). Idiopathic cases of erythroderma were mostly observed in 70–79 years' age group. Male patients (289;78%) outnumbered females (81;(22%) in a ratio of 3.6:1. Age and sex ratio data in our study agree with the previous reports.[1],[2],[3],[4]

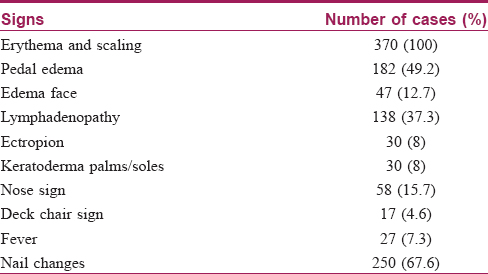

Pruritus was the most common symptom which was noted in all patients followed by chills in 333 (90%) patients. The other clinical features observed are shown in [Table - 1].

Lymphadenopathy was observed in 138 (37.3%) of patients with the most common site being inguinal and axillary nodes. Fine-needle aspiration cytology from enlarged lymph nodes was done in 120 patients, of which 118 (98.3%) showed features of dermatopathic lymphadenopathy, one showed lymphomatous infiltration and one case was inconclusive.

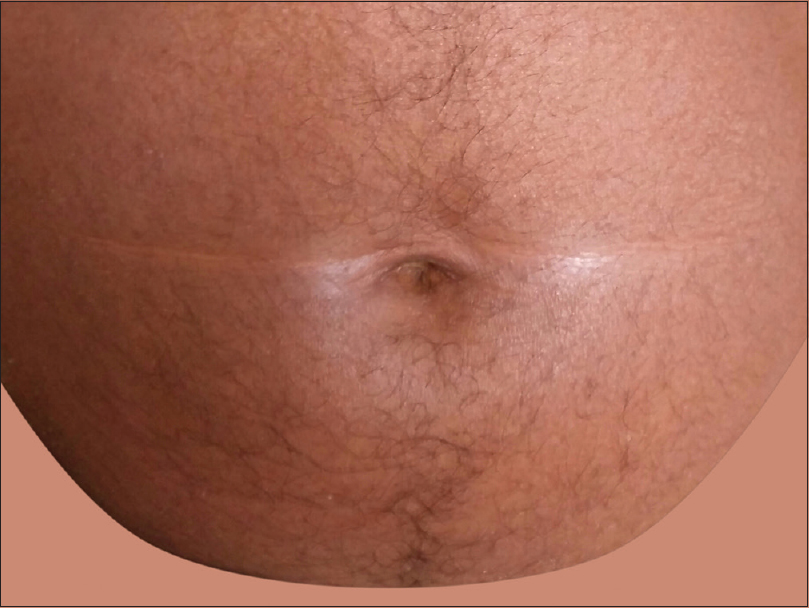

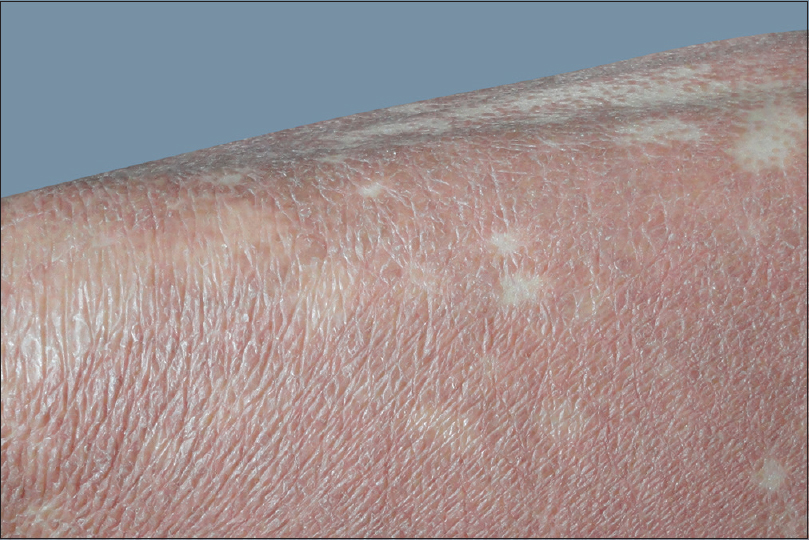

Nose sign [Figure - 1] was observed in 58 (15.7%) cases, but was not specific to any etiology. Pal et al. observed it in 13 (14.4%) cases while Hulmani et al. noted it in 16 (53.3%) patients.[1],[2] Deck chair sign [Figure - 2] was seen in 17 (4.6%) patients which included mycosis fungoides and chronic actinic dermatitis. This suggests the role of photosensitivity in this phenomenon as majority of our patients were outdoor workers. Pal et al. also observed similar findings.[2] Common nail changes were shiny nails, subungual hyperkeratosis, longitudinal ridging, pitting, onycholysis and nail dystrophy. Nail changes were most frequently seen in psoriatic erythroderma. Islands of normal skin were observed in two cases of mycosis fungoides, in addition to pityriasis rubra pilaris. Although considered a diagnostic feature of pityriasis rubra pilaris [Figure - 3], it is also reported in other conditions such as sarcoidosis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis and pemphigus foliaceus.[2] Laboratory investigations revealed anemia in 99 (26.8%) patients, leukocytosis in 18 (4.9%), eosinophilia in 56 (15%), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate in 98 (26.5%), hypoproteinemia in 32 (8.6%) and elevated liver enzymes in 10 (2.7%) patients. Three-fourth of the cases of drug-induced erythroderma showed eosinophilia.

|

| Figure 1: Nose sign |

|

| Figure 2: Deck chair sign |

|

| Figure 3: Islands of normal skin in pityriasis rubra pilaris |

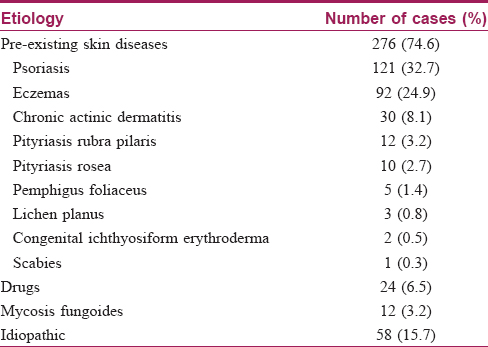

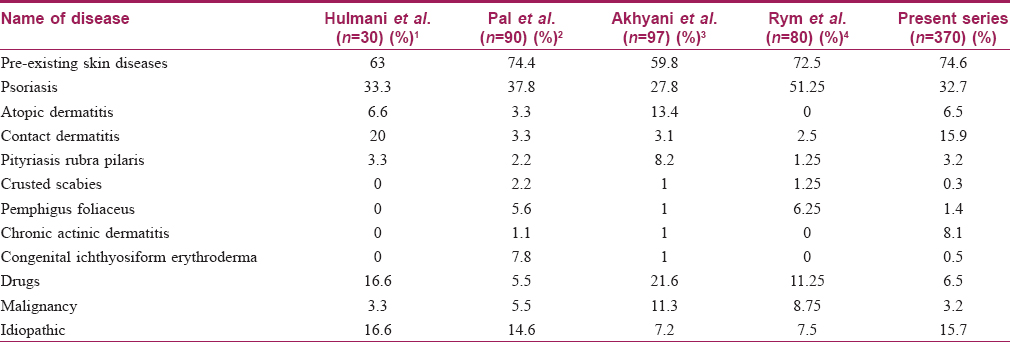

[Table - 2] summarizes the causes of erythroderma in our study.

As in previous studies, pre-existing skin diseases contributed the highest percentage of erythroderma; in our series (n = 276, 74.6%) psoriasis was the most common underlying disease.[1],[2],[3],[4] A comparison of etiology of erythroderma in various studies is shown in [Table - 3].

Chronic actinic dermatitis was noted in 30 (8.1%) patients which is high in comparison with other reports.[1],[2],[3],[4] The study area is a coastal district with white sandy soil. Albedo (percentage of light reflected from any surface) for sand is 15–30% which is higher than that of most ground substances (<10%).[5] This might have contributed to the high incidence of actinic dermatitis. Furthermore, most of our patients are engaged in outdoor occupations such as fishing and construction work.

Contact dermatitis was the most common type of eczema which was noted in 59 (15.9%) patients, followed by atopic eczema in 24 (6.5%), stasis dermatitis in 5 (1.4%) and seborrheic dermatitis in 4 (1.1%) patients (n = 370). The most common agent which caused contact dermatitis was cement followed by topical indigenous medicines. The high incidence of contact dermatitis in comparison with previous studies could be explained by the nature of occupation of people in our area.[2],[3],[4]

Drugs contributed 24 (6.5%) cases, of which phenytoin accounted for eleven. Other drugs observed to cause erythroderma were diclofenac, ibuprofen, allopurinol, carbamazepine, gemifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, INH, clonazepam and homeopathic drugs.

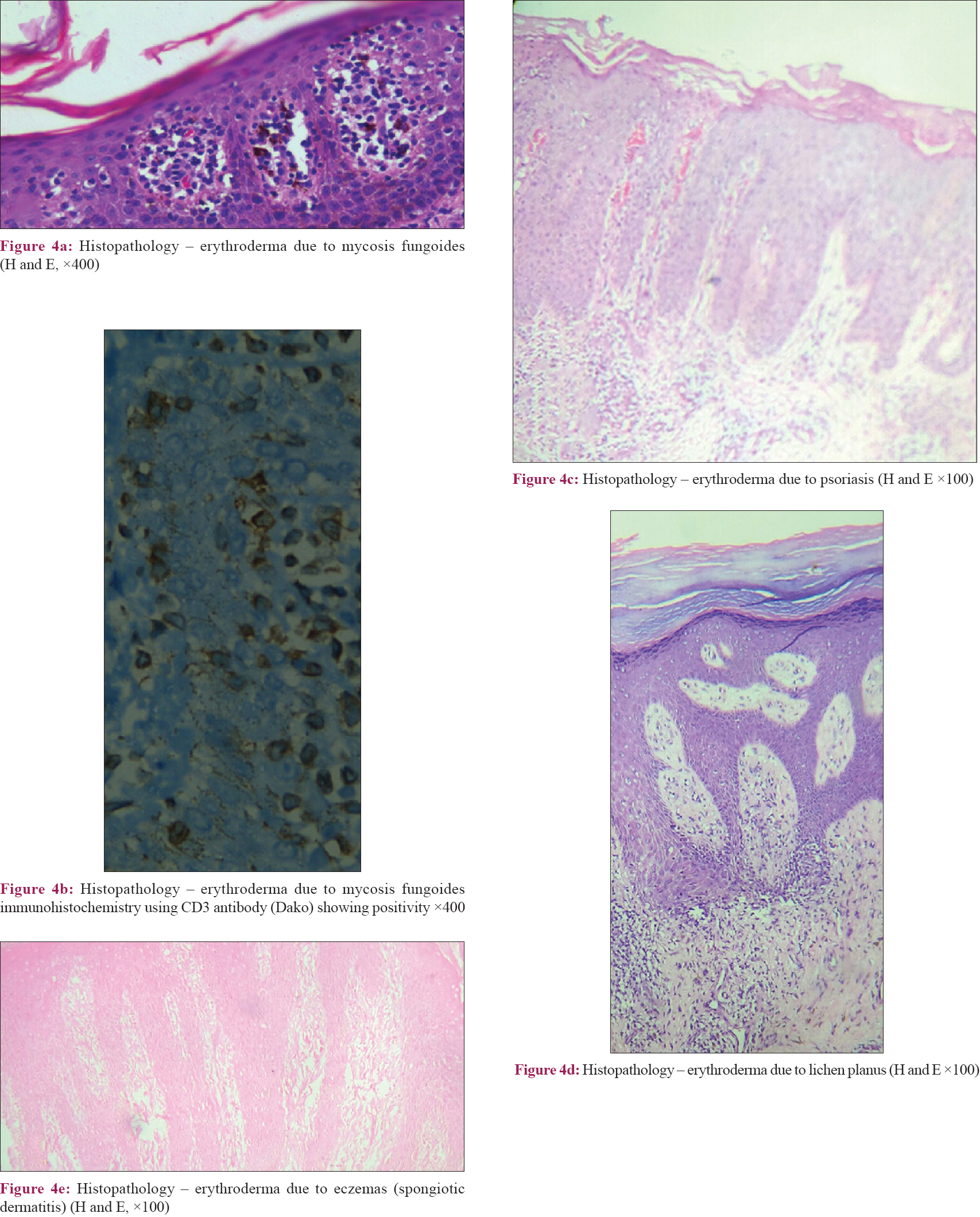

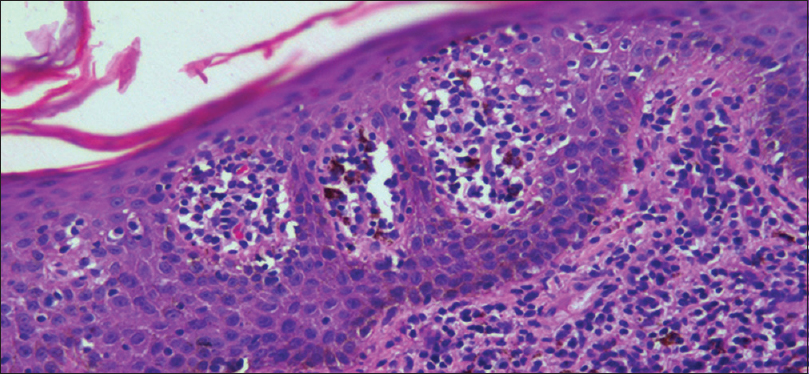

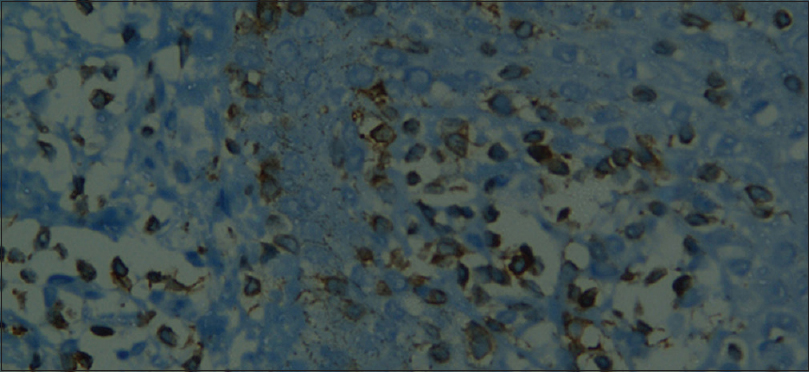

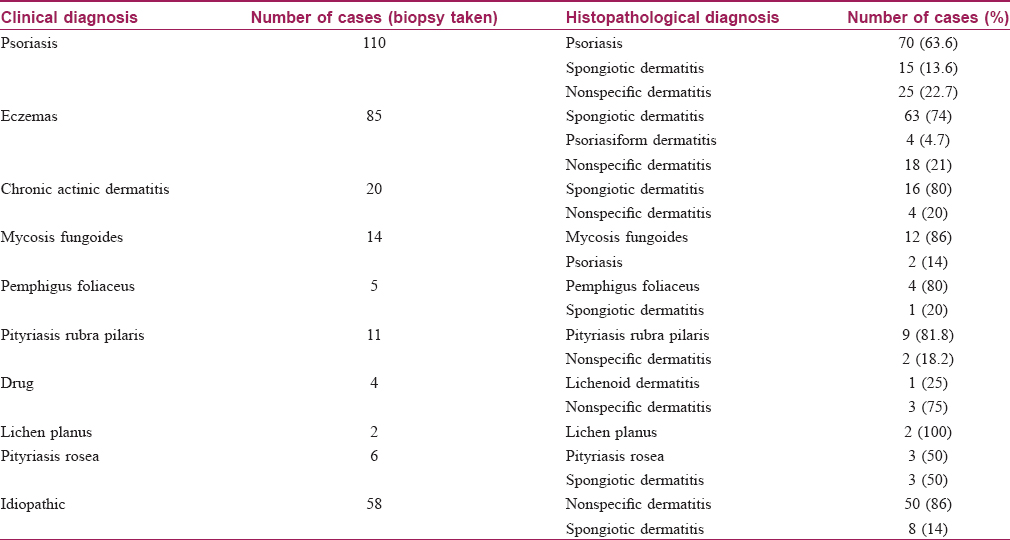

Skin biopsy was performed in 315 (85%) patients, details of which are shown in [Table - 4] and [Figure - 4]. Biopsy was avoided in patients where the cause was clinically obvious (pre-existing skin diseases and drugs). We obtained clinicopathological correlation in 180 (57.1%) cases. Best correlation was obtained in erythrodermic mycosis fungoides [Figure - 5] and [Figure - 6]. Hulmani et al. and Rym et al. observed a higher rate of correlation.[1],[4]

|

| Figure 4 |

|

| Figure 5: Histopathology of erythrodermic mycosis fungoides – epidermis showing Pautrier's microabscesses (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 6: Immunohistochemistry – CD3+ T-lymphocytes in mycosis fungoides ×400 |

Psoriasis patients were treated with emollients, phototherapy and methotrexate. A short course of systemic steroids was beneficial in many of our patients as contact dermatitis and actinic dermatitis were the common causes of erythroderma.

Our study highlights the role of various geographic and occupational factors in the etiology of erythroderma in a particular area. Knowledge about common causes in an area helps in better management of patients which, in turn, helps to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Hulmani M, Nandakishore B, Bhat MR, Sukumar D, Martis J, Kamath G, et al. Clinico-etiological study of 30 erythroderma cases from tertiary center in South India. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014;5:25-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Pal S, Haroon TS. Erythroderma: A clinico-etiologic study of 90 cases. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:104-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Akhyani M, Ghodsi ZS, Toosi S, Dabbaghian H. Erythroderma: A clinical study of 97 cases. BMC Dermatol 2005;5:5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Rym BM, Mourad M, Bechir Z, Dalenda E, Faika C, Iadh AM, et al. Erythroderma in adults: A report of 80 cases. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:731-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Khanna N, Sugandhan S. Photodermatology and photodermatoses. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008. p. 614-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,946

PDF downloads

1,826