Translate this page into:

Frictional amyloidosis in Oman - A study of ten cases

2 Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman

Correspondence Address:

Venkataram Mysore

Salmaniya Medical Complex, PB 12, Manama

Bahrain

| How to cite this article: Mysore V, Bhushnurmath SR, Muirhead DE, Al - Suwaid A. Frictional amyloidosis in Oman - A study of ten cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:28-32 |

Abstract

Macular amyloidosis is an important cause for cutaneous pigmentation, the aetiology of which is poorly understood. Friction has recently been implicated the causation of early lesions, referred to as frictional amyloidosis. Confirmation of diagnosis by the detect on of amyloid using histochemical stains is inconsistent. Ten patients with pigmentation suggestive of macular amyloidosis were studied with detailed history, clinical examination, biopsy for histochemistry and electron microscopy. Nine out of ten patients had a history of prolonged friction with various objects such as bath sponges, brushes, towels, plant sticks and leaves. Amyloid was demonstrated by histochemical staining in only six out of ten cases. In the remaining four cases, amyloid was detected by electron microscopy. These consisted of aggregates of non-branching, extracellular, intertwining fibres measuring between 200-500 nm in length and between 20-25 nm in diameter. The study confirms the role of friction in the causation of this condition. Histochemical stains are not always successful in the detection of amyloid and electron microscopy is helpful for confirming its presence. The term frictional amyloidosis aptly describes the condition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Macular amyloidosis, an important cause for cutaneous pigmentation, is characterised by dark pigmented macules, with a rippled pattern of pigmentation as a characteristic feature. The aetiology of the condition is not fully known. In 1988, Wong et all coined the term ′frictional amyloidosis′ to describe a highly characteristic type of pigmentation of the arms, forearms, interscapular areas, clavicles, and neck characterised by the presence of amyloid in the papillary dermis and predisposed to by repeated friction.[1] The condition had previously been described under various names such as peculiar reticulate pigmentation,[2],[3] frictional melanosis 4 and nylon friction dermatitis.[5] Early studies from Japan had recognised the role of friction in the causation of these lesions,[4],[5] Mizugacki 1984[6] demonstrated the presence of amyloid in some lesions with this condition. Wong et all discussed the similarities between macular amyloidosis and this condition, and suggested that the condition represented early lesions of macular amyloidosis and hence used the term frictional amyloidosis.[1] The authors also recognised the limitations of histochemical stains in the demonstration of amyloid and stressed the role of electron microscopy in confirming the diagnosis.

Most studies on the subject are from Asia and South America.[7] There is little information on this subject from the gulf region. In a recent study from Saudi Arabia, Jehad et al, 1997,[8] described 21 cases of cutaneous amyloidosis, including 10 cases of macular amyloidosis. In the present study, we describe 10 cases in the Sultanate Oman.

Materials and Methods

Ten patients presenting with suggestive clinical features of cutaneous macular amyloidosis were studied at the skin department, Baushar polyclinic the tertiary care referral centre in the Sultanate of Oman, during the period 1995 -96. A detailed clinical history of each patient was taken. Particular reference was given to the role of friction, type of friction and the material used for friction associated with each case. Other possible causes for pigmentation such as drugs and systemic illness were noted. Routine blood examinations, liver, renal and thyroid function tests were carried out. Skin biopsies were performed in all cases. The biopsies were sent fresh to the histology laboratory where they were bisected -one piece was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for light microscopy (LM) and the other piece trimmed into 1 x3 mm blocks of tissue for EM. The tissues for EM were fixed in Karnowsky′s fixative (2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5 % gluteraldehyde, PH 7.2 at 4°C, 2 hours). All tissues were processed according to the normal processing schedules for LM and EM.

On all paraffin sections, the following histochemical stains were performed and studied; haematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff, Masson Fontana, Congo red with polarisation, thioflavin T and crystal violet stains.

Electron microscopy was performed whenever the light microscopy was inconclusive.

Results

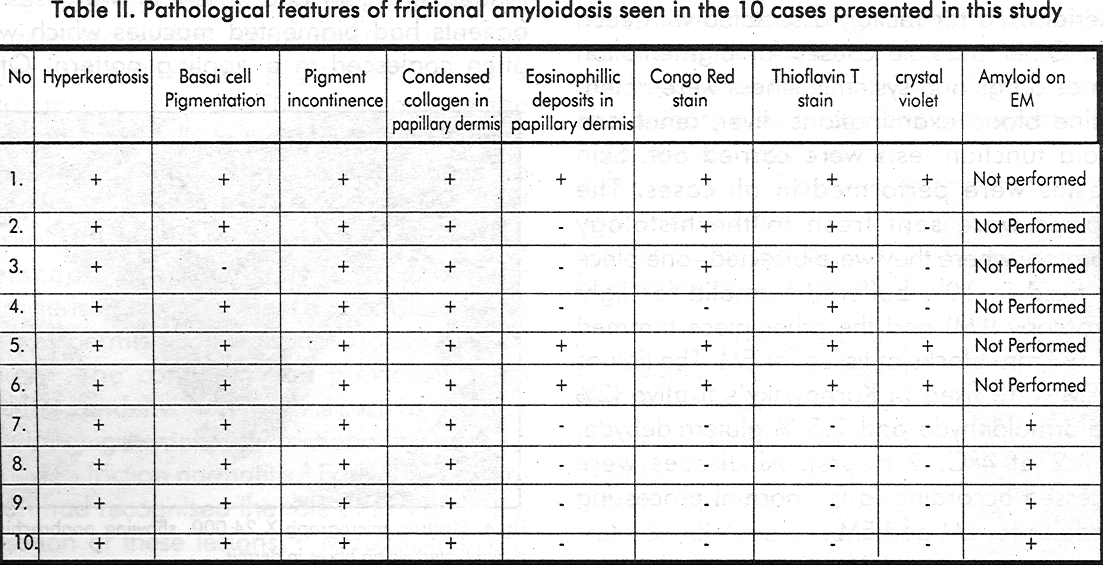

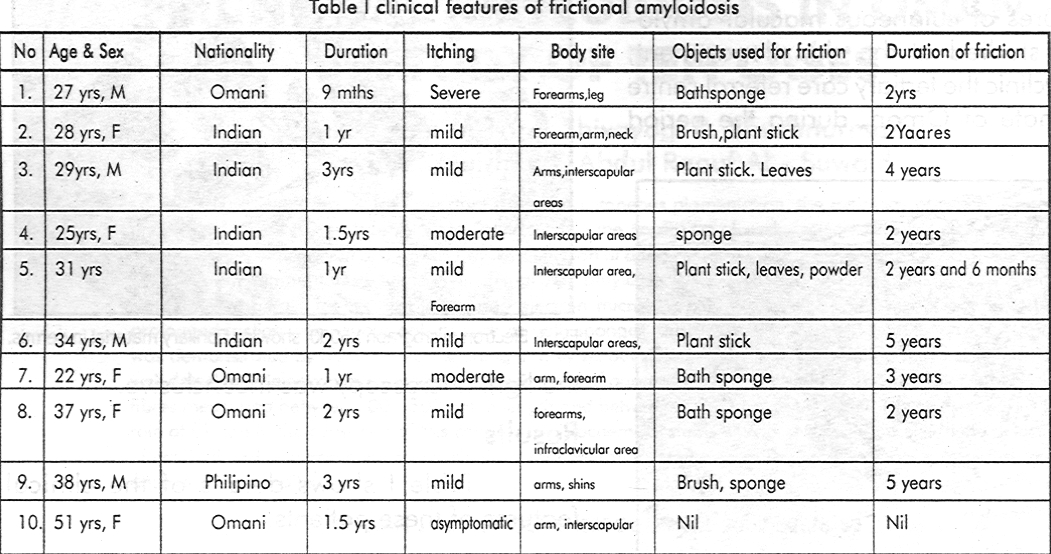

[Table - 1] shows details of the clinical features of these patients.

Of the ten patients, four were males and six were females. Patients ranged in age from 25 to 51 years. The patients were from different nationalities, including Indians (5 patients), Omanis (4 patients) and one Phillipino. The duration of lesions varied from nine months to four years. Itching was mild in four cases, moderate in four and absent in two cases. All patients had pigmented macules which were often coalesced in a rippling pattern. Other patterns such as papules (one patient), diffuse pigmentation due to coalesced macules (one patient) and associated lichen amyloidosis on the leg (one patient) were found. One patient had guttate hypopigemented lesions amidst areas of pigmentation on the arm.

Lesions were distributed over extensor surfaces of the arms, interscapular areas, shoulders, neck, infraclavicular areas and legs [Figure - 1]. Friction was the commonest predisposing factor, present in all except one of the ten cases. The various objects used for the friction were sponges used for bathing, nylon brushes, plant sticks, leaves and towels. Patients from South India used the plant sticks and leaves. The duration of friction varied from one to five years. Three patients had a history of exacerbation of the lesions on exposure to sunlight. One patient, a computer operator by profession, noted that the lesions became darker while working with computer, and faded during the weekends.

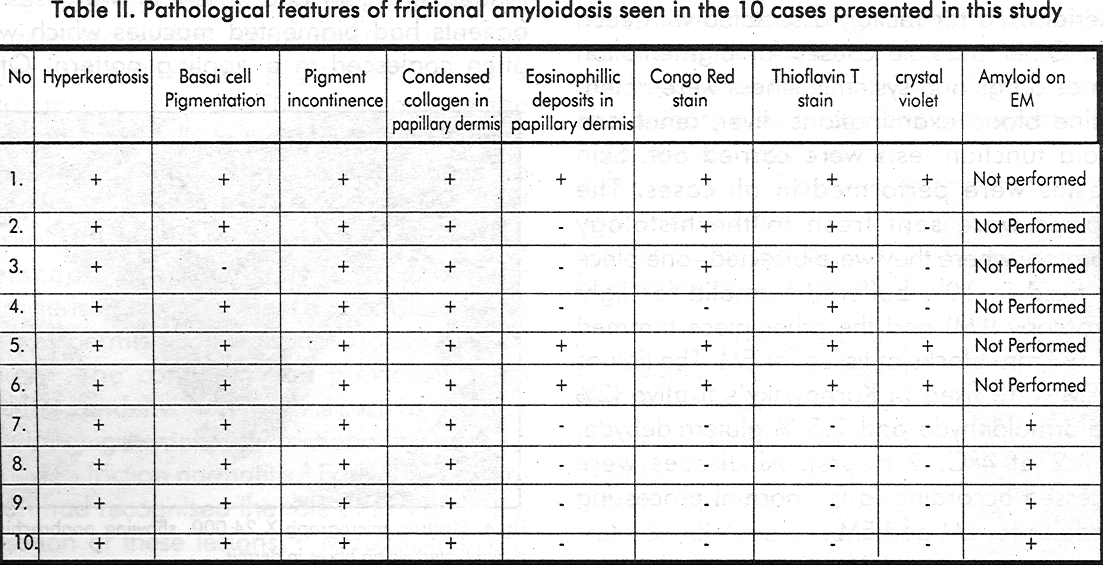

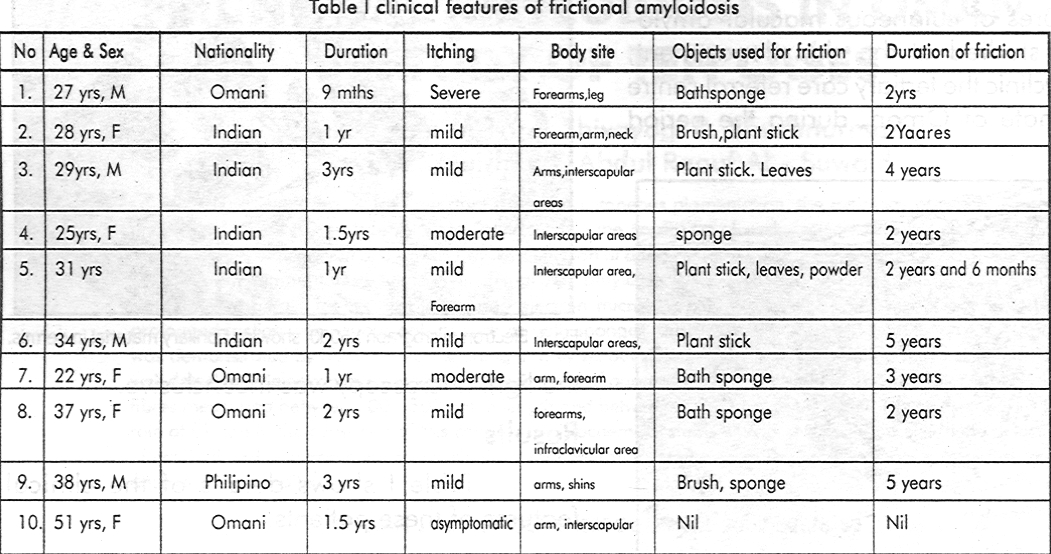

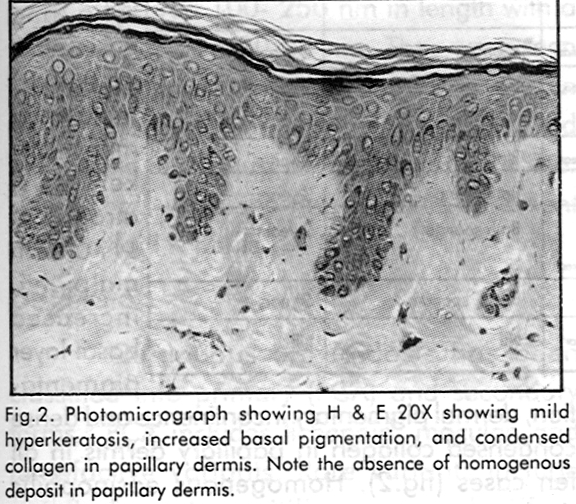

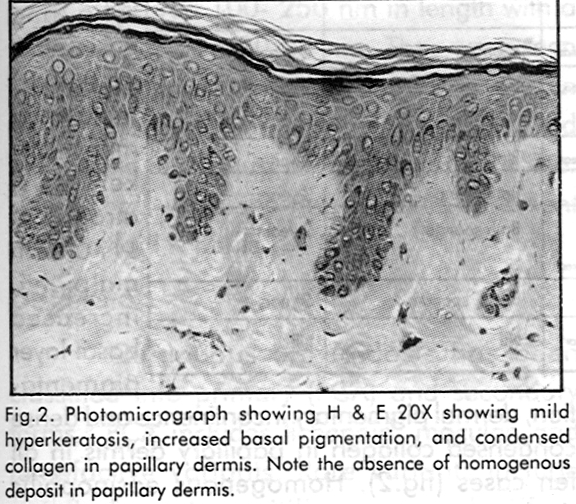

Histological features are shown in [Table - 2]. Routine haematoxylin and eosin stain showed features of mild hyperkeratosis, atrophy of stratum malpighii, increased basal layer pigmentation, dermal pigmentary incontinence and dense condensed collagen in papillary dermis in all ten cases [Figure - 2]. Homogenous eosinophilic deposits in papillary dermis suggestive of amyloid deposits, were seen in three cases. Basal cell degeneration was noted in one case. The special staining methods for amyloid demonstrated amyloid in only six of the ten cases.

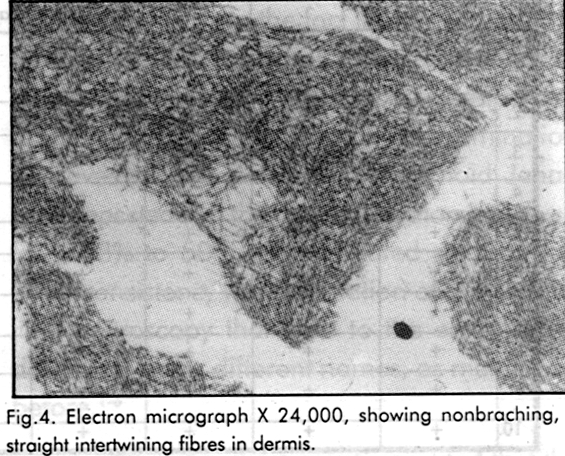

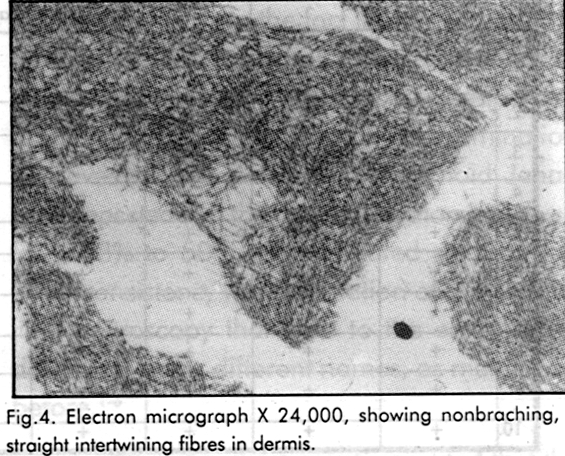

Electron microscopy demonstrated amyloid in the four cases that were inconclusive by light microscopy. Epidermis showed mild changes, including vacuolation of keratinocytes, with few organelles, increased tonofilaments and pyknotic nuclei. The ultrastructural examination of the dermis revealed small areas of extracellular fibrillary material [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4]. The fibrils were rigid, non-branching, straight or slightly curved, which were intertwining. The fibrils measured 100- 250 nm in length with a diameter between 20-23 nm. They were seen intermingling with the collagen fibres, and in longitudinal and transverse section, often found lying in the region just below the basal lamina. These fibrils were showing features consistent with amyloid K fibrils.

Discussion

Cutaneous amyloidosis has been classified into primary (PCA) and secondary forms.[7] PCA includes lichenoid, macular, and tumefactive variants. Rare variants include poikilodermatous,vitiligenous and diffuse pigmentation type.[7],[9] Macular variant was first described by Palitz and Peck in 1952,[10] and is characterised by dark pigmented macules, with a rippled pattern of pigmentation as a characteristic feature. The lesions are characteristically distributed over upper back, shins and arms. The diagnosis is usually based on the characteristic type of pigmentation and the typical distribution. Asians, Middle Easterners, South Americans, and Chinese seem particularly susceptible for this condition. The aetiology of this condition remains obscure, although environmental factors such as high humidity, temperature and genetic predisposition are thought to contribute to the aetiopathogenesis.[7]

The cases described here had the above described suggestive clinical appearance of macular amyloidosis. Significantly, nine out of ten patients, had history of prolonged rubbing with various objects such as sponges, nylon brushes, plant sticks and leaves. Duration of friction varied from 1-4 years. The role of friction in this macular variant was recognised by Japanese workers.[4] Subsequently, in a study of three patients, Wong et al[1] found nylon brushes, plastic objects, towels and fingernails to be the common objects used for friction. Our study confirms the role of friction in this condition. However, it is not yet clear how friction leads to amyloid formation and pigmentation. Friction has been shown previously to cause hyperkeratosis, damage to keratinocytes and stimulation of the melanocytes.[1] The keratinocyte damage, described as filamentous degeneration ultimately leads to the formation of amyloid.[9] However, the mechanism causing this effect is unknown. It has been suggested that the pigmentation in macular amyloidosis is a secondary phenomenon and the primary event is the formation of amyloid due to chronic friction.[1] In view of this, Wong et all suggested the name frictional amyloidosis and we feel this is an apt description.

In four of our cases, even with special stains, amyloid could not be detected by routine light microscopy. This finding has been reported before and is due to the fact that the amount of amyloid is often too small to be recognised in lesions of macular amyloidosis.[11] Sequential studies with meticulous histological examination improves the rate of detection of amyloid. Jehad et al[8] reported that the rate of detection improved from 38% to 50% after repeated studies. It is this inconsistency in confirmation of amyloid by light microscopy that lead to the entity being described under different names, as mentioned before.[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6]

It has been previously reported that the final reliable method of diagnosis is electron microscopy.[1],[10],[11] In a report from Japan, two out of six cases were negative for amyloid, which were later confirmed by electron microscopy.[6]

In the report by Wong et al,[1] histochemical stains failed to demonstrate amyloid in one of the three cases studied, which was confirmed subsequently by electron microscopy. These findings are substantiated by our experience, as electron microscopy helped to detect the presence of amyloid in the four cases that were initially negative by histochemical stains.

Thus, our study confirms the role of prolonged friction in lesions of cutaneous macular amyloidosis. The study also establishes the limitations of histochemistry in confirming the presence of amyloid and the usefulness of electron microscopy in identifying small amount of amyloid. In view of the small number of patients in our study, we feel that it will be interesting to conduct further electron microscopic studies in a bigger series of patients, with proper controls of uninvolved skin. This will further help in unravelling the aetiology of this condition.

| 1. |

Wong CK, Lin CS. Frictional amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol 1998; 27: 30-307.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Anekohji K, Meeda K, Shigemoto K, et al. A peculiar pigmentation of the skin (Japanese). Rinsho Dermatol (Tokyo) 1983; 23: 1259 - 1262.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Asai Y, Ramda T, Suzucki N, et al. Acquired hyperpigmentation distributed on the skin over bones (Japanese) Jpn J Dermatol 1983; 93: 405 - 414.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Hidano A, Mizhuguchi M, Rigaki Y. Melanose de friction. Ann Dermatol Venereal 1984; 111: 1063 -1071.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Tonagaki T, Hato S, Kitano Y. et al. Unusual pigmentation on the skin over trunk, bones and extremities, Dermatologica 1985;170: 235 -239.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Mizuguchi M, Okamura R. Six cases of macular amyloidosis mimicking pigmentation of frictional melanosis. Hifuka Rinsho (Tokyo) 1986;26: 173 -179.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Wong CK. Cutaneous amyloidosis (review). Int J Dermatol 1987; 26:273-277.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Jehad TA, Satti MB. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis; a clinicopothological study from Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol 1997; 36: 428 - 434.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Wen-Jen Wang. Clinical features of cutaneous amyloidosis. In: Cutaneous Amyloidosis. Wong CK, eds. Elsevier Science Pub NY 1990; 2 ; 13 -19.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Palitz LL, Peck S. Amyloidosis cutis: a macular variant. Arch Dermatol Syphilol 1952; 451 - 457.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Li WM. Histopathologicol features of cutaneous amyloidosis. In: Cutaneous Amyloidosis. Wong CK, eds. Elsevier Science Pub NY. 1990;2:1-19.

[Google Scholar]

|