Translate this page into:

Glucagonoma syndrome with atypical necrolytic migratory erythema

Corresponding author: Dr. Jinjing Jia, No. 111, Dade Road, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510120, Guangdong Province, China. 13310980167@163.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: He S, Zeng W, Geng S, Jia J. Glucagonoma syndrome with atypical necrolytic migratory erythema. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:49-53.

Abstract

Necrolytic migratory erythema is most commonly associated with glucagonoma syndrome. We report a rare case of glucagonoma syndrome with necrolytic migratory erythema presenting as pruritic papules and follicular pustules in a 57-year-old woman; showing eosinophilic infiltration on histology. However, the final diagnosis was confirmed by demonstrating neuroendocrine tumour on histopathological examination of the liver metastases. Nutrition therapy was administered as a palliative treatment. This case also highlights the atypical clinical features and nonspecific histology of necrolytic migratory erythema which makes the diagnosis difficult.

Keywords

Glucagonoma syndrome

necrolytic migratory erythema

nutrition therapy

Introduction

Glucagonoma syndrome is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of 1 in 20 million. It is an alpha-cell-secreting tumor of the pancreas, accompanied by multiple clinical features including a characteristic rash termed as necrolytic migratory erythema, weight loss and mild diabetes mellitus in most patients, whereas normochromic normocytic anemia, painful glossitis, cheilitis and angular stomatitis have also been reported.1-3 Necrolytic migratory erythema is the presenting sign in almost 82% of the affected patients.2

Case Report

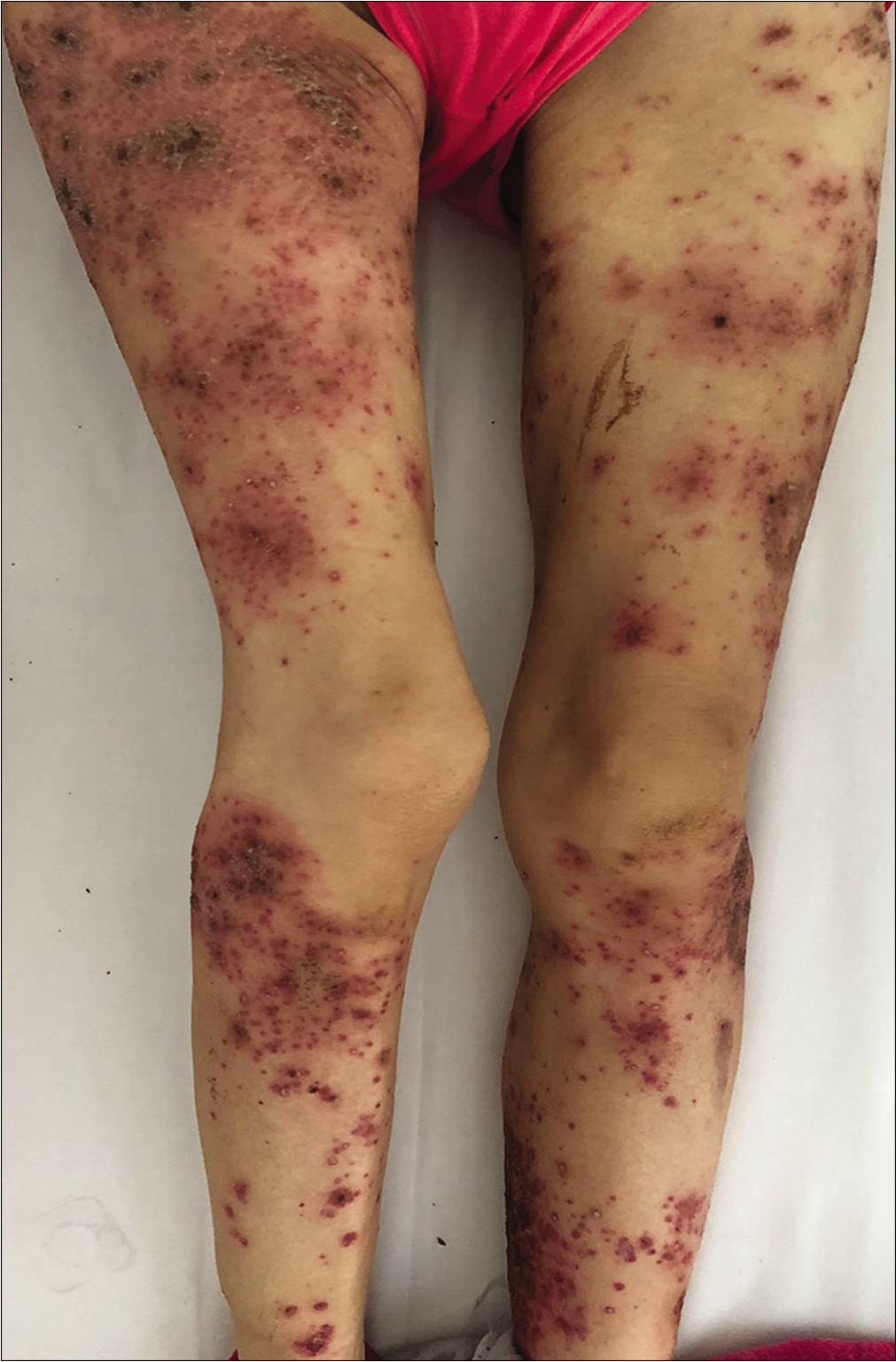

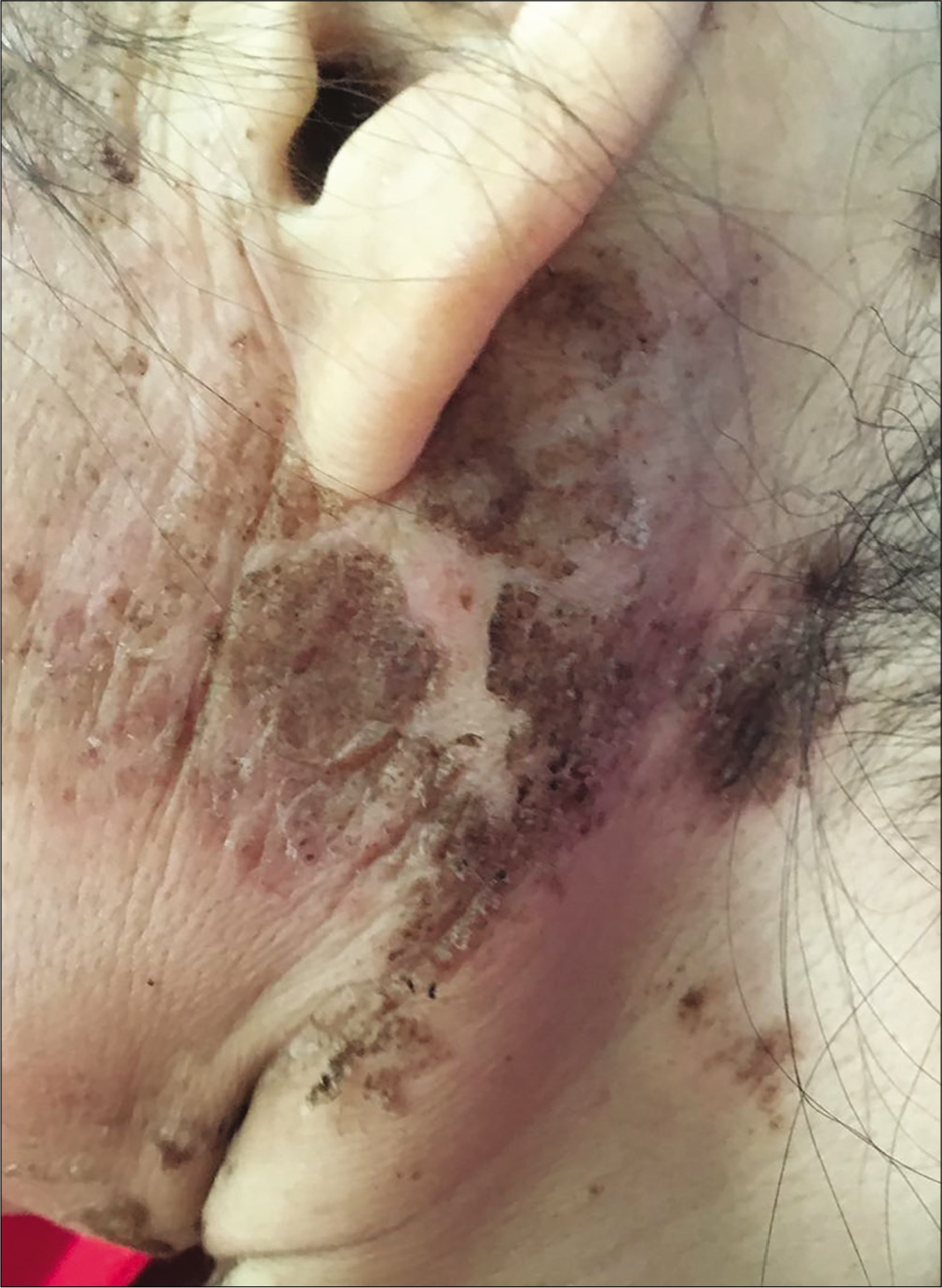

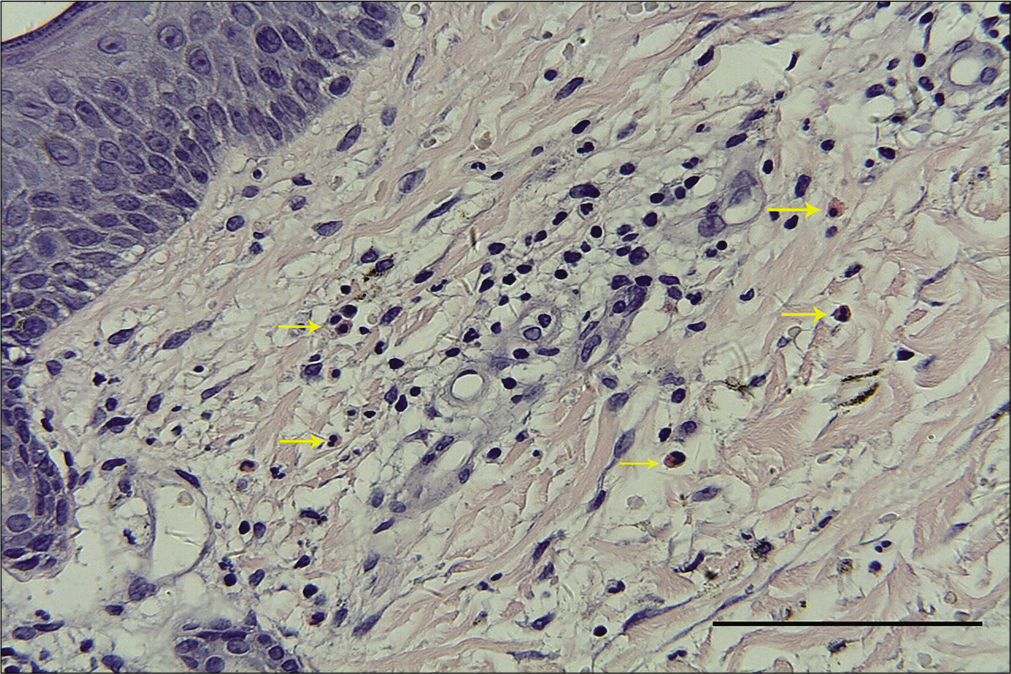

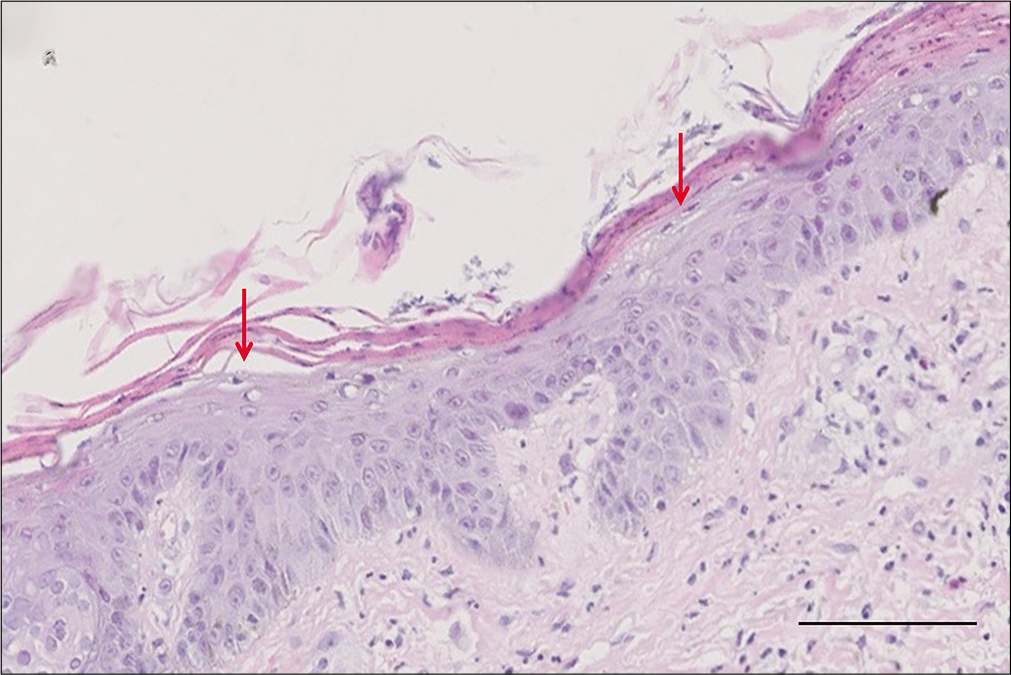

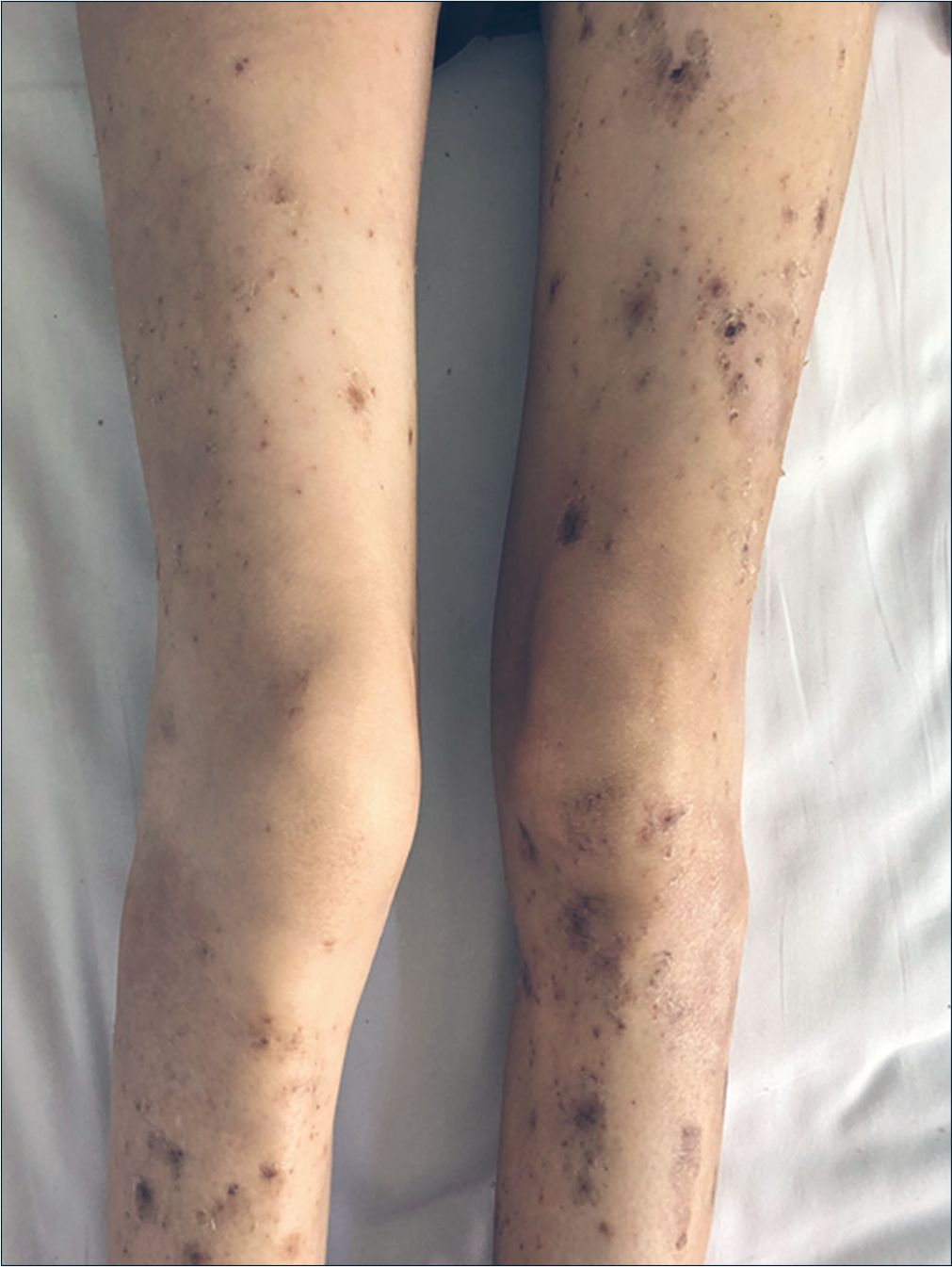

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our ward with persistent skin lesions for the last 16 days. She also complained of anorexia, fatigue, intermittent diarrhea and a 10-kg weight loss for last 1 year. Drug history was positive for oral mosapride citrate tablets and compound digestive enzymes. Scattered itchy papules and follicular pustules developed on an erythematous base following the intake of mosapride and digestive enzymes. Initially they appeared around her ears which rapidly spread to her neck, trunk and limbs. Subsequently, these lesions developed active annular erythematous borders and central crusting. Perioral desquamation, glossitis and angular stomatitis were also observed [Figure 1]. Her general examination was unremarkable except for hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biopsy of the skin lesions revealed showed perivascular moderate eosinophil infiltration in the edematous papillary dermis [Figure 2]. Based on clinicopathogical correlation, we diagnosed drug eruption and administered intravenous hydroprednisone, compound glycyrrhizin, 18 essential amino acids and some essential fatty acids. However, there was scarce clinical improvement and most of the original lesions developed scaling, crusting, slight residual hyperpigmentation.

- Erythematous scaly papules and pustules in the legs

- Erythematous scaly papules and pustules in the neck

- Erythematous scaly papules and pustules in the periauricular region

- Moderate eosinophil infiltration (yellow arrows) around the vessels in the edematous papillary dermis (H and E, ×400, bar length = 100 μm)

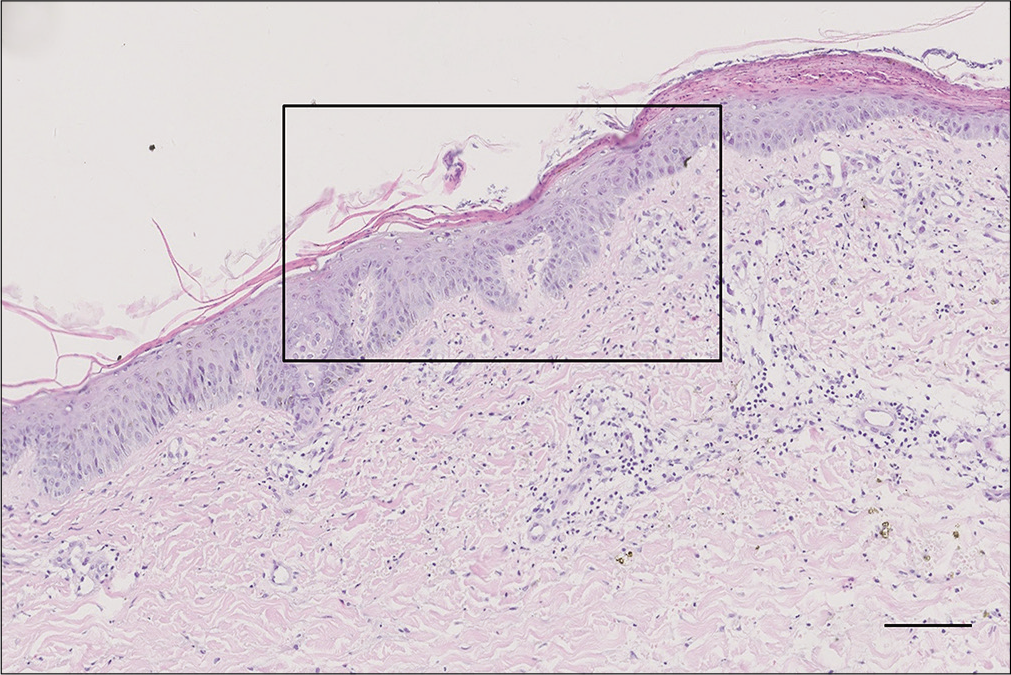

Routine blood biochemistry and bone marrow aspiration showed normochromic normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 74 g/L, red blood cells 2.4 × 1012/L, hematocrit 27.7%). The glycosylated hemoglobin level increased to 6.2%, and the albumin level decreased to 28.5 g/L (normal range 35–45 g/L). Enhanced abdominal computed tomography scanning revealed a 2 × 2 cm2 irregular mass on the tail of the pancreas along with multiple intrahepatic masses [Figure 3]. Further endocrinal investigations revealed a high level of glucagon at 3155.7 pg/mL (normal level ≤200 pg/mL); suggesting a diagnosis of glucagonoma with hepatic metastases. Repeat skin biopsy showed parakeratosis, intracellular edema and vacuolization in the upper spinous layer [Figure 4]. The histologic findings, along with the hormone levels, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and clinical presentation were together suggestive of glucagonoma syndrome with necrolytic migratory erythema. The presence of multiple metastases in the liver was a contraindication to surgery, and the patient refused chemotherapy because of concerns about adverse effects. After administration of octreotide and supplementation of amino acids, zinc and essential fatty acids, her lesions subsided with residual pigmentation [Figure 5].

- Enhanced abdominal computed tomography scan showing a mass in the tail of the pancreas (red arrow) and intrahepatic masses (yellow arrow)

- Magnification in black box in the upper spinous layer (H and E, ×100, bar length = 100 μm)

- Epidermal parakeratosis and vacuolated keratinocytes (red arrows) in the upper spinous layer (H and E, ×400, bar length = 100 μm)

- Obvious improvement of skin lesions on the legs

- Obvious improvement of skin lesions on the neck after treatment

Discussion

Early recognition of necrolytic migratory erythema is important because it can be the first and only manifestation of glucagonoma syndrome. The typical lesions of necrolytic migratory erythema initially appear as pruritic, irregular erythematous lesions with subsequent necrosis and crusting of the central part, leading to bullae, which progress to ulceration, crusting and scaling, and finally healing with hyperpigmentation.2,4-6 There are also some atypical presentations. Tremblay and Marcil had reported a case of necrolytic migratory erythema with vesicles and pustules in 2017.6 Toberer et al. also observed secondary pustules after erythema formation in a 38-year-old woman.7 The whole process evolves over a period of 2 weeks.1,5 Skin biopsy shows necrolysis of the upper spinous layer with confluent parakeratosis, pallor zone, vacuolated keratinocytes and keratinocyte degeneration. Lymphohistiocytic and neutrocytic infiltration can be found around the dilated vessels in the edematous papillary dermis.1,4,8

However, accurate diagnosis can be difficult, and necrolytic migratory erythema can sometimes be mistaken for other erythematous dermatoses. Urticarial vasculitis usually appears as an annular erythema similar to necrolytic migratory erythema. Eosinophilic cellulitis with edematous erythema, and eczema accompanied by erosions (pemphigus) also need to be differentiated. Skin biopsy and some extracutaneous observations can help confirm the diagnosis. Necrolytic acral erythema, which is closely associated with hepatitis C infection, bears microscopic and clinical resemblance to necrolytic migratory erythema.9 Drug eruption, which is usually characterized by the morphological diversity of the rash, may also cause diagnostic confusion. In our case, the patient had many classical extracutaneous features of glucagonoma syndrome. However, most of her lesions were itchy papules and follicular pustules, while typical erythematous vesicles and bullae were not observed. In addition, there was moderate eosinophilic infiltration of eosinophils in her histopathology, which has been barely reported previously. Though drug eruption was our primary diagnosis, mosapride and digestive enzymes are rarely the offending agents. The possibility of necrolytic migratory erythema was considered only after detecting a suspicious mass in the tail of pancreas. In retrospect, the clinical appearance of apparent erythematous base with active annular borders and central healing may help us identify necrolytic migratory erythema at the early stage. The second skin biopsy and other laboratory examinations finally confirmed the diagnosis of glucagonoma syndrome. Usually, by the time a diagnosis is made, at least 50% of patients already develop hepatic metastases. A curative surgical treatment is often impossible,3,6 as in our case. She also refused chemotherapy and other therapies, being apprehensive about their severe adverse effects. According to the pathogenesis of necrolytic migratory erythema, increased hepatocyte gluconeogenesis and lipolysis lead to hypoaminoacidemia resulting in epidermal protein deficiency and necrolysis. Additionally, nutritional or metabolic deficiency of zinc or essential fatty acids may play an important role. Therefore, somatostatin analogs, octreotide, amino acids and essential fatty acids are administered to relieve symptoms, and they also provide a good curative effect.1,2,10 Our case was also given similar treatment to result in symptomatic improvement. However, even if the pancreatic tumor is not removed, the course of glucagonoma syndrome can routinely exhibit spontaneous remission with reappearance of the skin lesions in the later stage; thus close follow-up such patients is needed.

Interestingly, all patients with glucagonoma syndrome do not present with typical migratory erythema. Early-stage or atypical necrolytic migratory erythema can manifest as erythematous, erosive, crusted plaques, which can be misdiagnosed as psoriasis vulgaris. Skin biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis with compact parakeratosis and morphologically consistent subcorneal pustules.11 Pustules and vasculitis-like lesions are being reported lately.

To conclude, necrolytic migratory erythema can appear in diverse forms on the base of erythema with annular borders. Dermatologists should be able to identify the main morphological characteristics of lesions, and in the presence of suspicious systemic symptoms, possible cutaneous manifestations of glucagonoma tumor should be considered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81803136), Guangzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Innovation Platform Construction Project (Guangdong Traditional Chinese Medicine Letter[2017] 340) and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Glucagonoma syndrome: A review and update on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2016-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucagonoma syndrome. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Feingold KR, Grossman A, Hershman JM, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: A clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normoglycemic glucagonoma syndrome associated with necrolytic migratory erythema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(8):e306-e307.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A review of cutaneous manifestations within glucagonoma syndrome: Necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:642-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necrolytic migratory erythema: A forgotten paraneoplastic condition. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:559-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema: The broad spectrum of the clinical and histopathological findings and clues to the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:e29-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delayed diagnosis of glucagonoma syndrome: A case report. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1272-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral amino acid and fatty acid infusion for the treatment of necrolytic migratory erythema in the glucagonoma syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;57:827-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasiform lesions: Uncommon presentation of glucagonoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:500-2.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]