Translate this page into:

Hennekam lymphangiectasia syndrome: A rare case of primary lymphedema

Corresponding author: Dr. Sarita Sanke, Department of Dermatology and STD, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Associated Hospitals, New Delhi - 110 001, India. sankesarita@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sanke S, Garg T, Manickavasagam S, Chander R. Hennekam lymphangiectasia syndrome: A rare case of primary lymphedema. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:240-4.

Sir,

Hennekam syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder resulting from malformation of the lymphatic system. This syndrome was first described by the Dutch physician Hennekam in 1989.1 It is a very rare syndrome and fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the medical literature.2 The characteristic signs of Hennekam syndrome are lymphangiectasia, lymphedema, facial anomalies and mental retardation.3

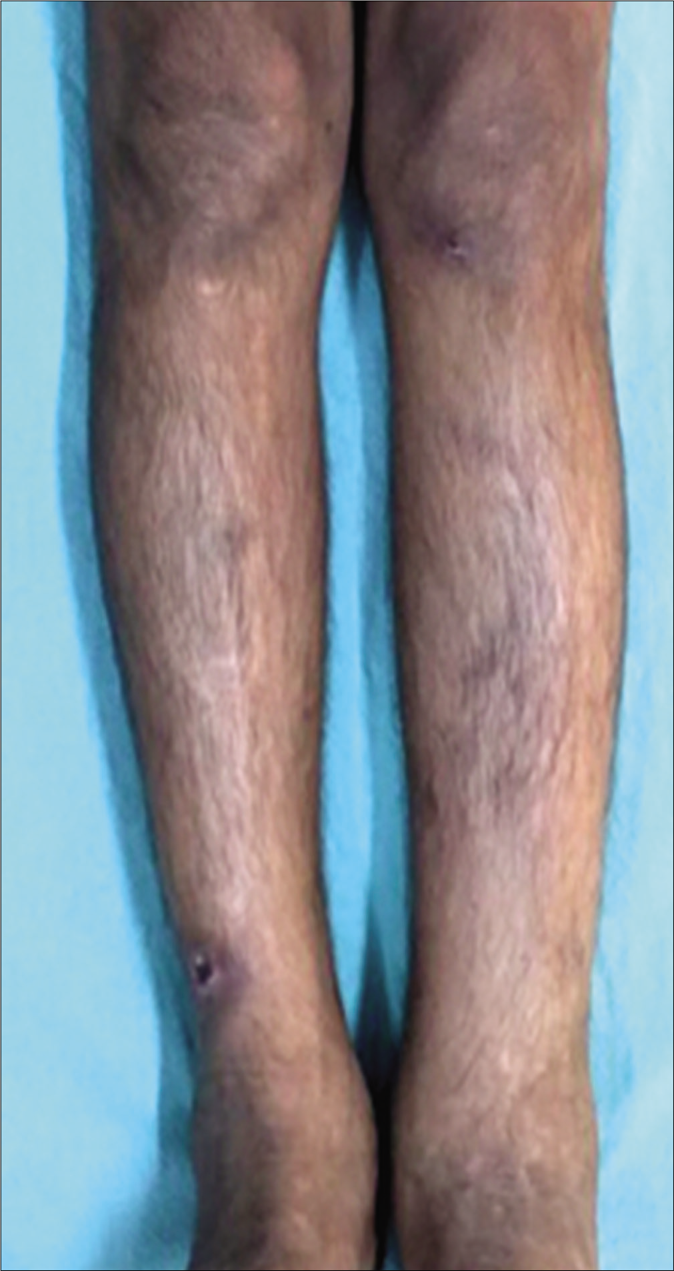

A 13-year-old boy from Uttar Pradesh, born out of consanguineous parentage, presented with edema of the external genitalia and both of his legs of 8-years duration. The edema had a fluctuating course (some days the right leg was more edematous, while in the other days the edema was more in the left leg, [Figure 1]). However, there was no diurnal variation. It was not associated with pain or tenderness. There was no history of prior radiation exposure, trauma or surgeries. There was no similar history in his family members. He had a past history of recurrent respiratory tract infections, since 6 months of age and history of recurrent diarrhea since he was 1 year old, which occurred approximately once in 2 weeks. He was evaluated and treated for lymphatic filariasis multiple times with no significant improvement.

- Edema of legs

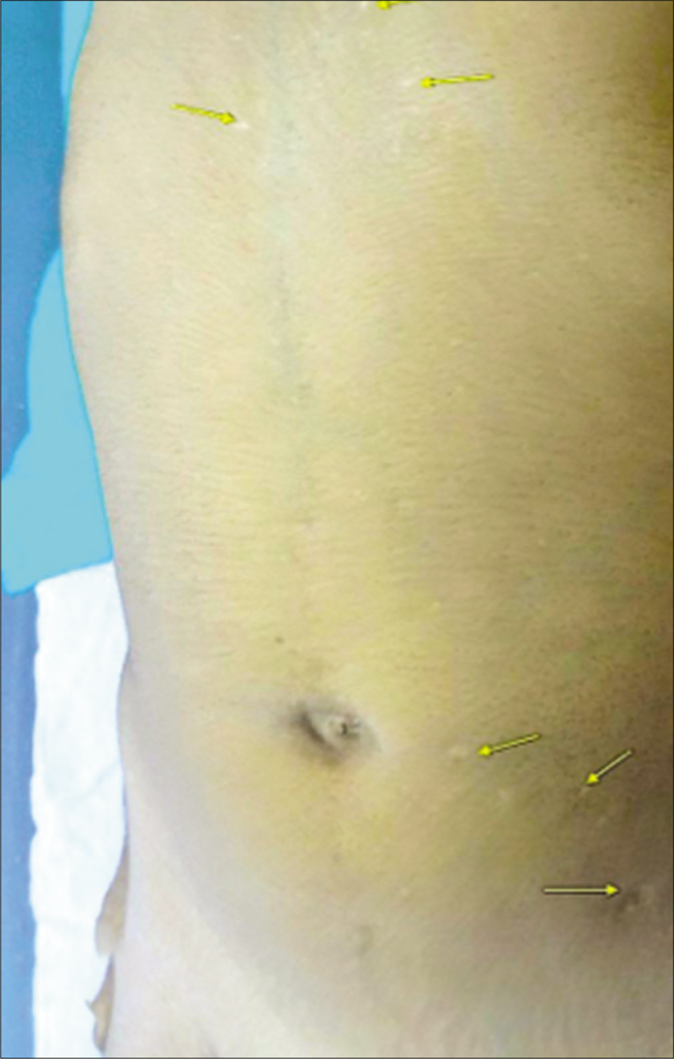

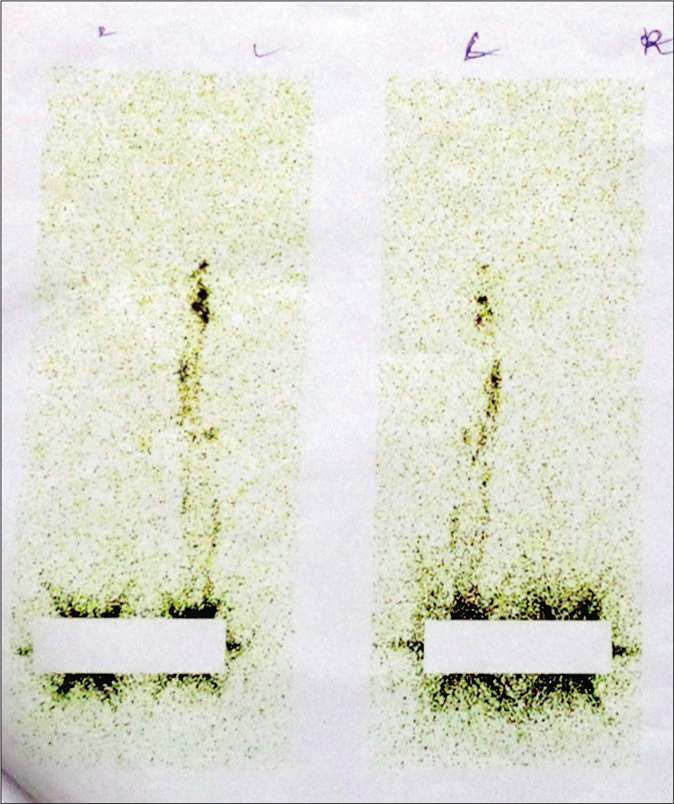

On examination, the patient had pallor and an antalgic gait. The facial features noted were synophrys, flat midface, bushy eyebrows [Figure 2a], Bitot spots of the eye [Figure 2b], smooth philtrum and thin upper lip. There was generalized dry, xerotic skin with multiple excoriation marks and atrophic scars on the body [Figure 2c]. Generalized hypertrichosis was also noted. Pitting pedal edema was present on both his lower limbs, extending just above the ankle joint.His external genitalia showed gross enlargement of scrotum and penis giving the appearance of “Saxophone penis”[Figure 3]. The great toenails showed Beau’s line, brownish discoloration and onychorrhexis [Figure 4]. There was malocclusion of the teeth with caries on oral examination. On investigations, he had anemia with hemoglobin of 8.1 g/dL, and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Serum immunoglobulins (IgG and IgM) were low. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was nonreactive. The rest of the investigations including chest roentgenogram, electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were normal. Peripheral smear after diethylcarbamazine provocation and microfilarial antigen test were, both negative. (Circulating filarial antigen detection test is now regarded as the “gold standard” for diagnosing Wuchereria bancrofti infections. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay methodology yields semi-quantitative results and has high sensitivity and specificity.) Ultrasound of the abdomen revealed massive splenomegaly, while that of the scrotum showed thickening of scrotal skin with connective tissue proliferation. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed features of duodenitis and few discrete pale-white areas on the duodenal mucosa. Biopsy of the same showed mild duodenal inflammation with few lymphangiectasias. Lymphoscintigraphy of the legs showed dermal backflow in the left lower calf region on the left leg. On the right leg, there was no tracer movement and non-visualization of inguinal and femoral lymph nodes [Figure 5]. These features were suggestive of primary lymphedema. Ophthalmology referral was taken which showed glaucomatous cupping of both eyes. Psychiatry opinion was sought and the child was found to have moderate mental retardation with an intelligence quotient of 48.

- Bushy eyebrows with synophrys, thin upper lip, smooth philtrum

- Bitot’s spots (Yellow arrow) with dry xerotic skin on the face (Blue arrow)

- Atrophic scars on the body (yellow arrows)

- Gross edema of the penis and scrotum (saxophone penis)

- The great toe nails showed Beau’s line, brownish discoloration and onychorhexis

- Lymphoscintigraphy of the legs showed dermal backflow at the left lower calf region on the left leg. On the right leg, there was no tracer movement and non-visualization of inguinal and femoral lymph nodes

Based on the above features, a provisional diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis and syndromic primary lymphedema were kept. Lymphatic filariasis was ruled out on the basis of the negative diethylcarbamazine provocation test and microfilaria antigen test. The syndromes of primary lymphedema that were thought of included Noonan syndrome, lymphedema distichiasis syndrome, Emberger syndrome and Hennekam syndrome. Table 1 enumerates all these possibilities with their differentiating points.

| Noonan syndrome | Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome | Emberger syndrome | Hennekam syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper torso lymphedema associated with typical facies Sparse eyebrows Webbed neck Rocker bottom feet Cognitive delay Congenital heart defects like pulmonary stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy PTPN11 mutations |

Asymmetric lymphedema of the legs (late childhood/adolescent onset)* Distichiasis Varicose veins Congenital heart disease Ptosis FOXC2 mutations |

Childhood onset* Unilateral or bilateral lower limb* +/− genital lymphedema* Myelodysplasia Hypotelorism, slender fingers, neck webbing, Multiple warts Erythroid transcription factor (GATA mutations) |

Asymmetrical lymphedema of limbs and genitalia* Lymphangiectasias* Mental retardation* Typical facies* Growth Retardation* Renal anomalies Glaucoma* Hearing defects Dental anomalies* Hypertrichosis* Anemia* Hypogammaglobulinemia Limb anomalies Blood vessel anomalies Central Nervous System anomalies |

| Unlikely | Unlikely | Unlikely | Multiple coinciding features |

CNS: central nervous system. GATA: Erythroid transcription factor

In view of the characteristic facial features, intestinal lymphangiectasias, borderline mental retardation and lymphoscintigraphy findings, a final diagnosis of Hennekam lymphangiectasias syndrome was made. Our patient was referred to a gastroenterologist and was advised to take low fat and protein-rich diet, along with supplements of vitamin A and vitamin D. Limb elevation and manual lymph drainage from distal to proximal leg, along with compression therapy (elastic crepe bandaging) was advised. For the xerosis, he was given emollients and antihistamines. However, the patient was lost to follow-up after a few weeks.

Hennekam syndrome is primarily a developmental disorder of the lymphatics with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. The etiology remains unknown, but the clinical features suggest that the syndrome results from abnormal development of the vascular and lymphatic systems, that disrupts critical events in craniofacial morphogenesis.1 Mutations of collagen and calcium-binding domain 1(CCBE 1)4 and FAT atypical cadherin 4 (FAT4)5 have been known to cause the disease. Mutational analysis in our patients was not done, due to the scarcity of resources. CCBE1 gene mutations that cause Hennekam syndrome, result in a change of the shape of the protein, thereby hampering its function in the formation of the lymphatic vessel epithelium. The resulting malformation of lymphatic vessels leads to lymphangiectasia and lymphedema. This malformation can affect any lymphatic vessel in any organ of the body. FAT4 gene mutations result in a FAT4 protein with decreased function which impairs the normal development of the lymphatic system, but the mechanism is unknown. The genotype registry includes various studies like sequence analysis of the entire coding region Hennekam lymphangiectasia-lymphedema syndrome type 1, complete CCBE1 gene sequencing, lymphedema sequencing panel with copy number variation detection, FAT4 mutation analysis, etc., The syndrome is characterized by a wide clinical spectrum with the association of lymphedema, intestinal lymphangiectasia, intellectual deficit and facial dysmorphism, being the most commonly encountered features. Altered lymphatic development before birth (intrauterine) may change the balance of fluids and impair normal development, contributing to dysmorphic facial features and poor brain development. Facial anomalies seen are the flat face, upper lip and nasal bridge, hypertelorism, epicanthal folds, synophrys, bushy eyebrows, craniosynostosis, atresia of the ear canal, smallmouth, retrognathia, oligodontia and conical crowns. The dermatological anomalies described are severe lymphedema of the limbs, face and genitalia, infection of oozing lymphatics (erysipelas) and alopecia areata. Glaucoma is also noted in some of the cases.

The most characteristic anomaly reported in the gastrointestinal tract is intestinal lymphangiectasia. Tortuous, dilated mucosal and submucosal lymphatic vessels, due to increased lymphatic pressure are the hallmark of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia.6 These intestinal lymphangiectasias could be the cause of recurrent diarrhea in our patients. The congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasis is a rare developmental disorder of the pulmonary lymphatic vessels which is associated with Hennekam Syndrome. Urogenital anomalies described are genital lymphedema, duplicated ureter, hydroureteronephrosis, chyluria (rupture of renal lymphangiectasis lacteals) and cystitis due to vesicoureteral reflux.7 However, our patient did not have any renal involvement. Treatment is symptomatic.3 Many patients are treated with total parenteral nutrition, a medium-chain triglyceride-rich diet and albumin infusions. Fat-soluble vitamins and electrolyte supplements, together with a high-protein diet have been reported to be beneficial. The lymphedema may be severely disabling and require repeated surgical intervention. The prognosis is variable and few patients have been described with very severe manifestations leading to an early death.2 To conclude, all cases of lymphedema in a child are not necessarily due to filariasis. A dermatologist needs to work up the case thoroughly to exclude all the syndromes with primary lymphedema.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Autosomal recessive intestinal lymphangiectasia and lymphedema, with facial anomalies and mental retardation. Am J Med Genet. 1989;34:593-600.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymphedema lymphangiectasia mental retardation (Hennekam) syndrome: A review. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:412-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutations in CCBE1 cause generalized lymph vessel dysplasia in humans. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1272-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam syndrome can be caused by FAT4 mutations and be allelic to Van Mal dergem syndrome. Hum Genet. 2014;133:1161-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam lymphangiectasia In: Text Book of Gastroenterology (5th ed). US: Wiley Blackwell; 2008. p. :1101-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous manifestations and massive genital involvement in Hennekam syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:239-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]