Translate this page into:

Intravenous immunoglobulin for the management of Netherton syndrome

Corresponding author: Dr. Shekhar Neema, Department of Dermatology, AFMC, Pune, Maharashtra, India. shekharadvait@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Neema S, Vasudevan B, Rathod A, Mukherjee S, Vendhan S, Gera V. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the management of Netherton syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:754-6

Dear Editor,

Erythroderma indicates generalized erythema and scaling involving more than 80–90% body surface area. There is a long list of differentials for neonatal and infantile erythroderma, including primary immunodeficiency syndromes, ichthyosis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, langerhan cell histiocytosis, infections like staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and scabies, drug induced, metabolic and nutritional disorders like biotin metabolism disorders, acrodermatitis enteropathica and urea cycle disorders.1 Netherton syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by triad of icthyosiform erythroderma, trichorrhexis invaginata and atopic manifestations. Icthyosis linearis cirumflexa represents double-edged scale and is pathognomonic for diagnosing Netherton syndrome, however, it is not a constant feature.2 We present a genetically confirmed case of Netherton syndrome treated with intravenous immunoglobulin.

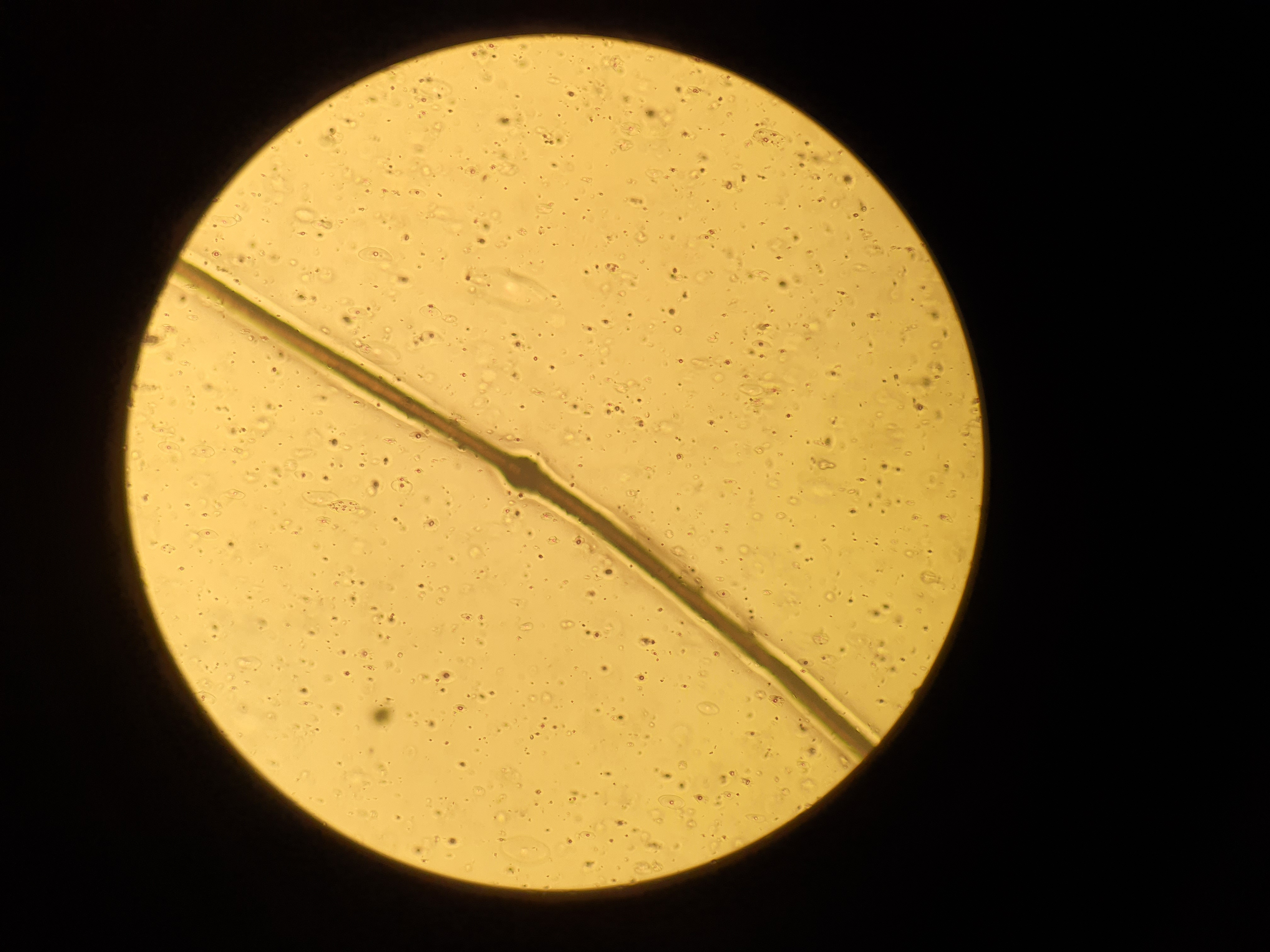

A 11 months-old-girl, first child of second-degree consanguineous marriage, was brought to us with generalized erythema and scaling involving her body and sparse, dry and fragile hair since birth. She was delivered preterm (32 weeks period of gestation) with low birth weight (2100 gms). None of the family members, first or second degree were suffering from similar problems. There was history of poor weight gain, but vomiting, diarrhoea, malodorous secretions or similar complaints were absent. General examination revealed severe under-nutrition (weight- 5.2 kg, < -3 SD), severe stunting (length- 59 cms, < -3 SD) and microcephaly (occipito-frontal head circumference- 40 cms < -3 SD). Developmental examination suggested global developmental delay with developmental age around nine months. She had no organomegaly. Dermatological examination showed involvement of more than 80% body surface area with erythema and scaling [Figure 1]. Oozing was noted on the flexors of both forearms. Her hair was sparse, dry and fragile. Icthyosis linearis circumflexa was noted [Figure 2]. Trichoscopy demonstrated nodes in the hair shaft and broken hairs of various lengths with a frayed paint-brush-like appearance [Figure 3]. Direct microscopic examination confirmed trichoscopic findings [Figure 4]. Langerhan cell histiocytosis, primary immunodeficiency syndromes, Netherton syndrome and biotinidase deficiency were considered as differential diagnoses. Skin histopathology showed flattened rete pegs, hypogranulosis, mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and absence of CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Laboratory evaluation revealed normal electrolytes, liver and renal function. Her immunodeficiency workup including immunoglobulin profile, lymphocyte subset analysis, complement levels and nitroblue tetrazolium test were normal except for raised serum IgE (510 IU/mL). Serum biotinidase levels were within normal limits. Clinical exome analysis revealed homozygous, single base pair insertion in exon 26 of the SPINK5 gene (chr5:g.148120311_148120312insA; depth: 161x) that resulted in frameshift and premature truncation of the protein, four amino acid downstream to codon 824. This variant was classified as pathogenic in ClinVar database. The mutation was not confirmed by Sanger sequencing. She was treated with multiple courses of oral steroids (1 mg/kg/day), syrup cyclosporine (5 mg/kg/day), topical emollients and mid-potent steroids over the last five months, with partial response. Due to poor response to the first line treatment; continued symptomatology with scaling, severe pruritus and irritability, she was administered intravenous immunoglobulin 400 mg/kg/day every four week. She responded promptly one week after the first cycle and has been under remission on monthly IVIG along with daily emollients and intermittent topical steroids. She has been administered three such cycles and we plan to continue monthly IVIG [Figure 5].

- Erythema and scaling involving more than 80% body surface area. The scaling is more prominent in flexures

- Clinical image shows classical icthyosis linearis circumflexa with double-edged scales

- Trichoscopy shows white scales, nodes on the hair shaft (blue arrow) and broken hairs (polarised dermoscopy, Dermlite DL4 ×10)

- Hair microscopy shows node on the hair shaft (dry mount, ×400)

- Improvement seen after intravenous immunoglobulin

The diagnosis of Netherton syndrome is usually difficult in early infancy as icthyosis linearis cirumflexa is not a constant feature and hair shaft abnormalities may develop later. The diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic studies; however, their cost is prohibitive in resource-poor settings. Netherton syndrome is associated with functional and phenotypic defects in several lymphocyte subpopulations and is classified as a primary immunodeficiency disorder.3 The current treatment options for Netherton syndrome include skin cleansing, antibiotics, bleach bath, topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antihistamines and oral steroids. Retinoids and phototherapy show variable effects. Various other modalities have been tried in recalcitrant cases, not responding to first-line options, and include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), infliximab, secukinumab, ustekinumab, omalizumab and dupilumab.2,4,5 The exact mechanism of action of IVIG in Netherton syndrome is unclear, however, restoration of abnormal antibody response and increased natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity may result in its beneficial effect.6 Table 1 highlights the cases of Netherton syndrome which received IVIG. It is difficult to perform large-scale studies for this rare disorder, so evidence regarding new drugs is mostly anecdotal. Intravenous immunoglobulin has achieved success in most cases, and appears to be safe and effective for managing Netherton syndrome, especially those not responding to the first-line treatments.

Reference

Number of patients

Dose

Follow-up duration

Response

Renner ED et al.

7

5

0.4gm/kg/month

2 years

Excellent response

Zelieskova M et al.

8

1

0.4 gm/kg/month IV X 3 months followed by 200 mg/kg/month SC

12 months

Excellent response

Saenz R et al.9

3

Not mentioned

Not mentioned

Minimal improvement

Ragamin A et al.

10

2

0.4 gm/Kg/Month

6 month -2.5 years

Excellent response lasted 6 month in first patient and 2.5 years in second patient

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Netherton syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:346-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immune cell phenotype and functional defects in Netherton syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:213.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Netherton syndrome with dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:350-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secukinumab therapy for Netherton syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:907-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Response to low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in a case of recalcitrant Darier disease. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:189-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comèl-Netherton syndrome defined as primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:536-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A novel SPINK5 mutation and successful subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in a child with Netherton syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:1202-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The difficult management of three patients with Netherton syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:S134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment experiences with intravenous immunoglobulins, ixekizumab, dupilumab, and anakinra in Netherton syndrome: A case series. Dermatology 2022:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]