Translate this page into:

Isolated Crohn's disease of the vulva

2 Department of Gastroenterology, P. D. Hinduja Hospital and MRC, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim, Mumbai-400 016, Maharashtra, India

Correspondence Address:

Nina A Madnani

Department of Dermatology, P. D. Hinduja Hospital and MRC, Mumbai, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, Khan KJ. Isolated Crohn's disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:342-344 |

Sir,

Vulvar ulceration due to Crohn′s disease is an extremely rare condition with only a few reported cases. [1] Patients usually suffer for years before being correctly diagnosed and treated. We report a case of Crohn′s disease of the vulva presenting as a chronic, non-healing ulcer, without any gastrointestinal involvement.

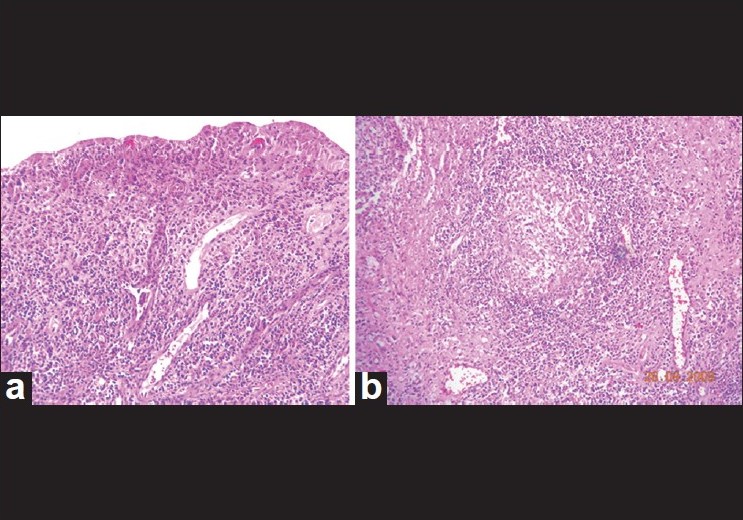

A 37-year-old married female presented with complaints of painful, persisting vulvar ulcers, and resulting dysperunia for 4 years. She had no oral ulcers or bowel complaints and treatment with systemic acyclovir, doxycycline, and fluconazole had failed. She responded to systemic corticosteroids but relapsed immediately on discontinuation. Clinical examination revealed multiple, tender, indurated ulcers with beefy red granulation tissue distributed in a horse-shoe pattern around the clitoris. A single "knife-cut" linear, deep ulcer with sharp vertical margins was also seen involving the left labia majora and minora and the entire clitoris [Figure - 1]. The vagina and cervix were normal. She had no inguinal lymphadenopathy, perianal ulceration, abscess, or skin tags. Our differential diagnosis at this stage included Behcet′s disease, amoebic ulcer, vulvar Crohn′s disease, cutaneous tuberculosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, hidradenitis suppurativa, syphilis and sarcoidosis. The routine hematologic work-up including VDRL, ELISA for HIV, and ACE levels was normal, except for a raised ESR of 42 mm. Tissue smears for organisms and Donovan bodies were negative. A biopsy from the lesional skin stained with hematoxylene-eosin (HandE) showed an ulcerated epidermis. There was a diffuse lympho-plasmacytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with several scattered non-caseating epitheloid cell granulomas [[Figure - 2]a, b]. Giemsa and AFB stains were negative for organisms. Mycobacterium culture (including atypical mycobacteria) and TB-PCR were negative. In view of the clinical and histopathological features, a diagnosis of Crohn′s disease of the vulva was made by exclusion.

|

| Figure 1: Multiple fleshy ulcers seen involving labia majora, minora, and clitoris. A single "knife-cut" ulcer seen in the left clitoral-labial groove |

|

| Figure 2: (a) Ulcerated epidermis showing diffuse infiltration with inflammatory cells. (H and E, ×100). (b) Deeper dermis shows multiple non-caseating epitheloid-cell granulomas (H and E, ×200) |

The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist to rule out bowel involvement. A barium meal follow-through study and colonoscopy were normal. Ileal biopsy and multiple colonic tissue biopsies did not demonstrate any inflammation or granulomas. A final diagnosis of isolated Crohn′s disease of the vulva without intestinal involvement was made. The patient was advised systemic metronidazole, 400 mg three times daily. Her ulcer showed dramatic healing within 6 weeks [Figure - 3] and the metronidazole was continued for a year with complete healing of the ulcers. However, as she developed signs of peripheral neuropathy, metronidazole had to be discontinued. But the ulcers relapsed. Azathioprine was then introduced at a dose of 100 mg daily with minimal improvement at the end of 3 months. The patient was subsequently lost to follow up.

|

| Figure 3: Excellent response to oral metronidazole within 6 weeks of initiating therapy |

Crohn′s disease is a chronic granulomatous, inflammatory disorder of unknown pathogenesis. Although it can involve any section of the bowel, the ileo-caecal junction is most commonly involved. Extra-intestinal cutaneous manifestations of Crohn′s disease, like erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, are well known. [2] Ulcerative vulvar Crohn′s disease was first described by Park et al. [3] It is very rare, and less than 60 such cases have been described. [4] Although the average age of presentation is 34 years, there have been reports in children as young as 8 years of age. [5] Patients may initially present with swelling, erythema, pruritus or pain, and subsequently develop unilateral vulvar hypertrophy, vulvar mass, vulvar edema, draining sinuses, ulceration, or abscess formation. "Knife-cut" ulcers which resemble lacerations are almost pathognomonic of Crohn′s disease although they have been reported in herpetic infections in the immunocompromised and in cutaneous tuberculosis. "Apthous-like" ulcer is the other morphological presentation seen. Vulvar involvement in Crohn′s disease may be by virtue of contiguity, as a direct extension of intestinal involvement, or non-contiguous (metastatic) in which there is no connection between the vulva and the bowel. [6] In a review by Andreani et al., 91% of cases of vulvar Crohn′s disease had metastatic spread, while only 5% had contiguous spread. [4] In the same study, 25% of vulvar Crohn′s disease did not have any intestinal involvement at the time of the vulvar lesion. It is in these cases that making a correct diagnosis becomes difficult. Werlin et al., have reported that vulvar ulcers may precede intestinal manifestations by up to 18 years. [7] Initial stages of vulvar Crohn′s disease can be medically managed. Metronidazole alone or in combination with steroids has been the most effective treatment with a success rate of 87.5%. [4] The optimal recommended dose of metronidazole is 20 mg/kg/day for at least 12 to 36 months. [8] Bilateral pedal paresthesia is a complication reported with long-term metronidazole. Other drugs like sulfasalazine, azathioprine, infliximab, and thalidomide have been used with varied response. Advanced cases may require vulvectomy, but local excision has been reported to show recurrence of the disease.

Chronic vulvar ulcers require thorough clinical evaluation and long term follow-up for a successful outcome.

| 1. |

Kingsland CR, Alderman B. Crohn's disease of the vulva. J R Soc Med 1991;84:236-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, Smidt A, Stika CS, Schlosser B, et al. Clinical Spectrum of Vulva Metastatic Crohn's Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:1565-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:241-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn's disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010;8:2-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Lally MR, Orenstein SR, Cohen BA. Crohn's disease of the Vulva in an 8-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol 1988;5:103-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Bohl TG. Vulvar ulcers and erosions-a dermatologist's viewpoint. Dermatol Ther 2004;17:55-67.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Werlin SL, Easterly NB, Oechler H. Crohn's disease presenting as unilateral labial hypertrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:893-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ, Frank MS. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: A follow-up study. Gastroenterology 1982;83:383-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,816

PDF downloads

2,374