Translate this page into:

Leaving a mark: Multiple geometric areas of alopecia

2 Department of Dermatology and STD, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

3 Department of Pathology, Yenepoya Medical College, Manipal University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

Corresponding Author:

Hima Gopinath

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Madagadipet, Puducherry - 605 107

India

hima36@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Gopinath H, Kuruvila M, Naik R, Sreedharan S. Leaving a mark: Multiple geometric areas of alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:373-375 |

Sir,

Post-operative alopecia is a rarely reported group of scarring and non-scarring alopecia.[1] It usually presents as a solitary oval patch, most commonly on the occiput.[2] We report a case, where a patient developed multiple geometric areas of alopecia following contact with objects on the scalp during the intra-operative and post-operative period, corresponding to the shape and area of pressure from the objects.

A 13-year-old boy presented with a 1-month history of patchy hair loss. Two months prior to the presentation, he had undergone an 8 hours long endoscopic nasal and nasopharyngeal extended skull-based resection, for extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. His head was positioned on a “ring” shaped head rest [Figure 1a] throughout the surgery, during which repositioning was not done. There was massive blood loss (estimated loss of 3 L) and hypotension (30–90 mmHg systolic and 20–60 mmHg diastolic) in the intraoperative period, followed by postoperative intubation and immobilization in the intensive care unit for 1 day.

|

| Figure 1a: "Ring" shaped headrest |

On examination, there were multiple well-defined areas of cicatricial and noncicatricial alopecia in the parieto-occipital region of the scalp. The central areas within the lesions were indurated and had a brownish hue. Central confluent circles of alopecia were surrounded by peripheral arcuate areas [Figure 1b]. The areas of alopecia corresponded to the areas of pressure from the “ring” shaped head rest (arcuate lesions) and the bed (central confluent lesions). Cicatricial hair loss was seen in the central portions of the arcuate lesions, corresponding to the areas of maximum pressure from the convexity of the ring-shaped head rest.

|

| Figure 1b: Central confluent circles and peripheral arcuate areas of scarring and nonscarring alopecia |

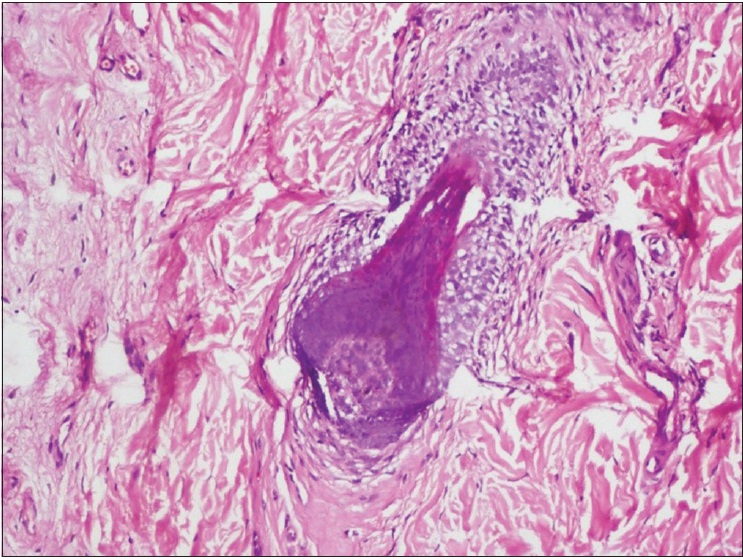

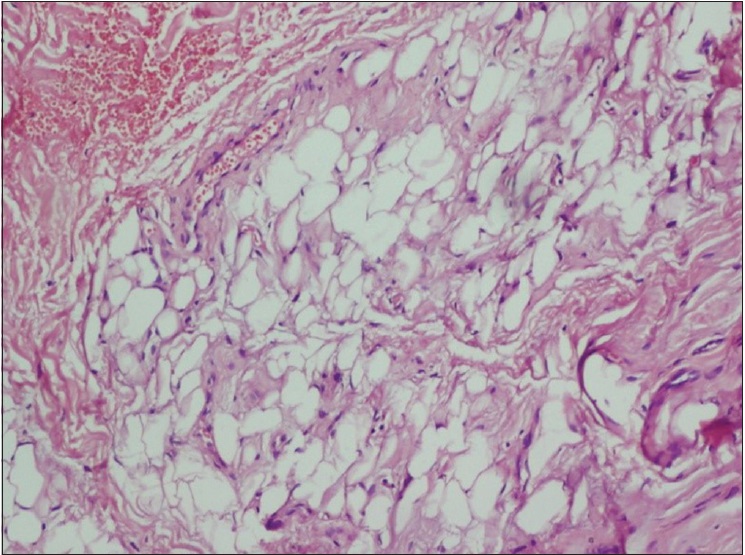

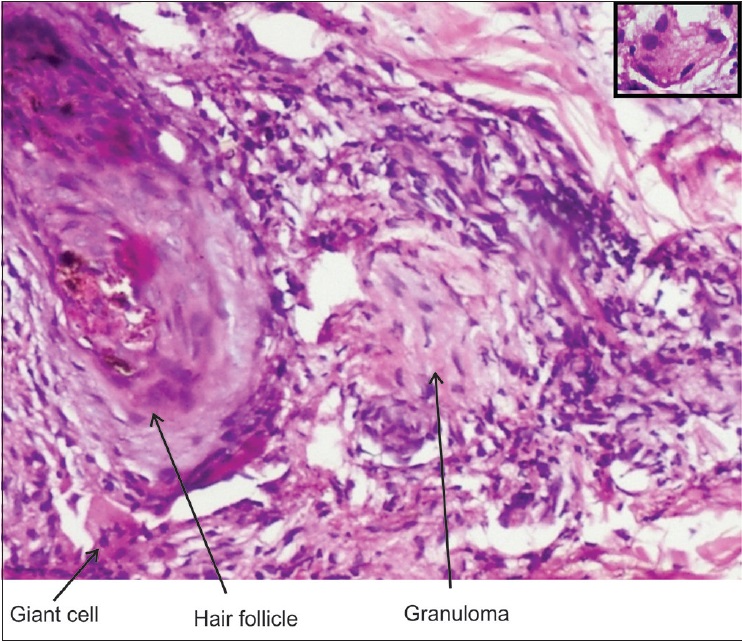

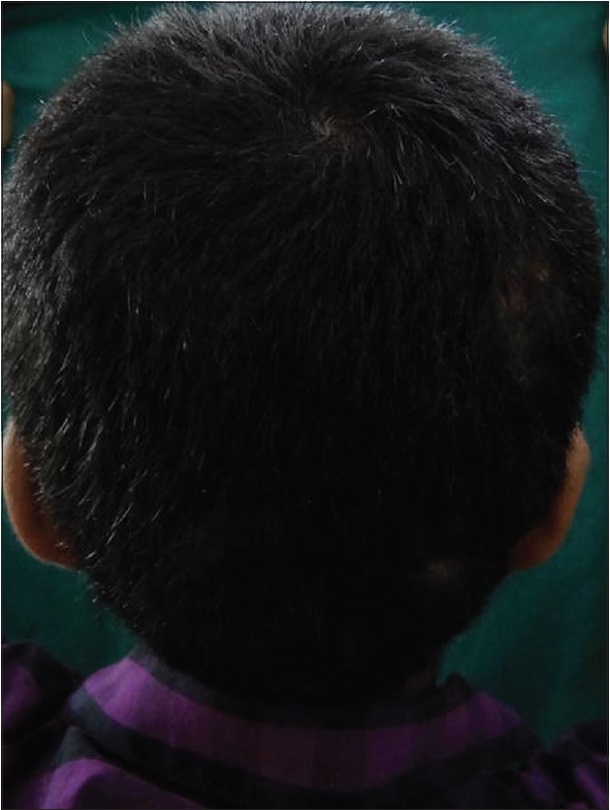

A biopsy revealed decreased number of hair follicles, predominantly in the telogen phase, focal fat necrosis, dermal fibrosis and granulomatous inflammation. The findings were consistent with pressure alopecia [Figure 2a],[Figure 2b],[Figure 2c]. The patient was counseled regarding the likelihood of spontaneous regrowth, and as expected, spontaneous regrowth was seen in most areas except for some islands of scarring in the right parietal and occipital regions, on follow-up after 3½ months [Figure 1c].

|

| Figure 2a: Telogen hair surrounded by fibrosis (H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 2b: Focal fat necrosis (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 2c: Hair follicle with granuloma. Giant cell in the inset |

|

| Figure 1c: Regrowth in most areas on follow-up after 3½ months |

Postoperative (pressure) alopecia was first described by Abel and Lewis in 1959.[1] It occurs following major surgical procedures (cardio-thoracic, gynecological, abdominal, plastic and reconstructive and neurological), prolonged immobilization and rarely, after blunt trauma.[2],[3] Pressure alopecia has also been reported with the use of headband, headrest and orthodontic head gear. Tissue hypoxia and ischemia secondary to continuous pressure on the selected regions has been suggested as one of the etiological factors. It has been compared to a healed pressure ulcer. The duration of pressure is also an important risk factor. Intraoperative hypotension can exacerbate the tissue ischemia.[1],[3]

Pressure alopecia mainly affects the posterior region of the scalp.[3] There is no age predilection and has been reported even in neonates.[1] Early manifestations in the first few days can include swelling, pain, exudation, crusts, central erythema and induration. Rapid, sharply demarcated hair loss ensues usually within 28 days.[2],[4]

Histopathological changes vary with the evolution of alopecia. Synchronized conversion of most or all terminal hairs to catagen/telogen phase is characteristic. Alopecia areata can be differentiated by the absence of nanogen hairs, miniaturization and focal peribulbar inflammation. Absence of distorted follicles and incomplete follicular anatomy may help in excluding trichotillomania. Other reported changes in postoperative alopecia include vasculitis, thrombosis, vascular congestion, fat necrosis, trichomalacia, pigment casts, loss of hair follicles, chronic inflammation, foreign body granulomas and dermal fibrosis.[1],[2],[5]

Postoperative application of topical minoxidil or corticosteroids is of doubtful efficacy.[3] The time under general anesthesia has also been reported to be a risk factor for permanent alopecia. Severe hypoxia can cause inflammation and fibrosis and result in permanent alopecia.[6]

Increased awareness about pressure alopecia and more vigilance regarding the objects in contact with the scalp during prolonged surgeries or immobilization are needed. The headrest, often used as a pressure-relieving device, can result in additional areas of alopecia. Although our patient had unusual multiple areas of alopecia, the history, location, geometric shapes, presence of scarring and histopathology helped in the diagnosis of this rare alopecia. Pressure ulcer prevention strategies such as frequent repositioning and support surfaces might prevent this cosmetic mishap.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Soujanya Gandla, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kasturba Medical College, for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. | Davies KE, Yesudian P. Pressure alopecia. Int J Trichology 2012;4:64-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Sperling LC, Cowper SE, Knopp EA, editors. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlation. 2nd ed. New York: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Domínguez-Auñ ón JD, García-Arpa M, Pé rez-Suárez B, Castañ o E, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Guerra A, et al. Pressure alopecia. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:928-30. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Abel RR, Lewis GM. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia. Arch Dermatol 1960;81:34-42. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Siah TW, Sperling L. The histopathologic diagnosis of post-operative alopecia. J Cutan Pathol 2014;41:699-702. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Pressure alopecia: Clinical findings and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:188-9. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,940

PDF downloads

2,391