Translate this page into:

Leprosy in Robben Island: Historical and medical insights and a comparative study with India

Corresponding author: Dr. Prakhar Srivastava, Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, Delhi, India. sriprakhar1996@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Srivastava P, Dev PP, Srivastava P, Khunger N. Leprosy in Robben Island: Historical and medical insights and a comparative study with India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:554-6. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_839_2023

Introduction

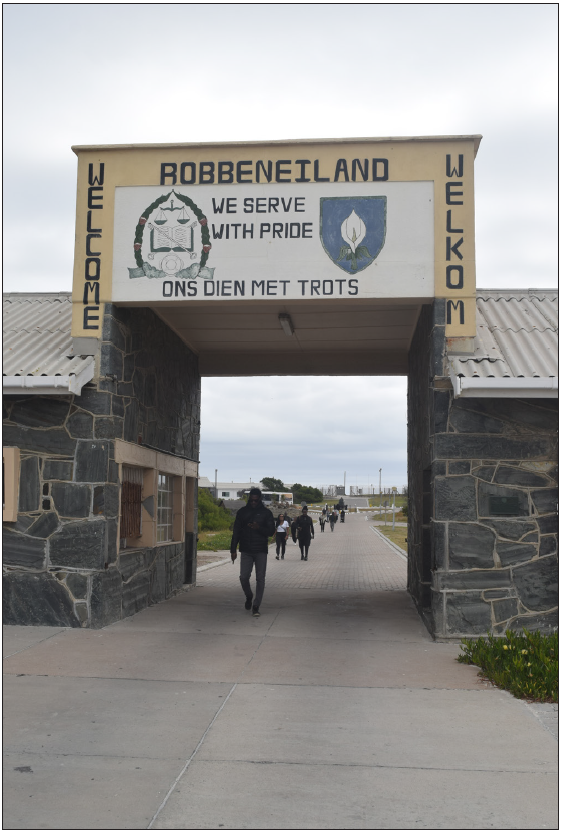

In October 2022, we visited Cape Town, South Africa, to attend the 22nd International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. Apart from expanding our medical horizons, this trip granted us a special privilege to explore the historical and medical dimensions of leprosy in South Africa. We visited Robben Island, situated 11 km from South Africa’s mother city, Cape Town, on 13th October 2022 [Figure 1]. Robben Island is a South African National Heritage Site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. ‘Robben’ is the Dutch word for ‘seal’. We reached the island via a ferry which departed from the Nelson Mandela Gateway at the V&A Waterfront. The Island has been a place of banishment, exile, isolation, and imprisonment for nearly 400 years. Through this article, we will delve into the profound historical context of leprosy on Robben Island and its medical evolution, and draw parallels with the stigmatisation of leprosy in India. By examining these intricate facets, we hope to gain valuable insights into the impact of this disease on individuals, societies, and medical understanding.

- The entrance gate to Robben Island, with an inscription saying ‘Ons Dien Met Trots’, Dutch for ‘We serve with Pride’.

Historical perspectives: Robben Island and leprosy

Robben Island, a flat Island in the Western Province of South Africa, is an infamous symbol of political imprisonment, which also harbours a lesser-known yet equally significant history as a leprosy colony. The infirmary for leprosy was established on Robben Island in 1846, during British colonial rule.1 During the 1840s, the Island became popular for its dry sea breezes, which contrasted with the stereotypical island humidity. It provided a perfect location for sea bathing, which was considered beneficial for health, particularly for leprosy patients. During the same time, the Colonial Medical Committee recommended the transfer of leprosy patients to the Island. In the 1850s, the Medical Committee suggested that the Robben Island climate made it ‘an excellent sanitary station’.2

The island served as a place of isolation for leprosy patients. The prevailing misconception of leprosy’s extreme contagiousness during this era fuelled this isolation policy. Isolation, driven by the fear of transmission, led to the segregation of leprosy patients from their families, communities, and society at large. After 45 years of the initial establishment of a leprosarium on the Island, the Cape Government passed the Leprosy Repression Act in 1891, which stripped people with leprosy of their civil rights and banished them to the Island.3 Most of these isolated chronically ill people were black Africans who were the poorest of the colonial population and the rest were European immigrants with lesser community support structures [Figures 2 and 3].

- Isolation chambers in the Robben Island compound for both the apartheid political prisoners as well as the leprosy patients.

- Common ground in between the isolation chambers with a high brick wall secured by barbed fenced wires.

The historical context sheds light on how limited medical knowledge and prevailing misconceptions perpetuated fear, discrimination, and immense suffering for those afflicted. The leprosarium cemetery came into existence during the infirmary period, the remains of which can still be seen [Figure 4].

- The remains of ‘Leper Graveyard’, with hundreds of named and unnamed tombstones.

Medical progression: Leprosy understanding and treatment

In 1931 the Island’s leprosy hospital was closed. The years that followed the closure of the leprosy hospital coincided with the active involvement of Great Britain in the Second World War. The medical journey from the days of Robben Island’s leprosy colony to the present has been marked by remarkable advancements in understanding and treating leprosy. Leprosy, caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae, primarily affects the skin, nerves, and mucous membranes. Modern scientific understanding has debunked the notion of leprosy’s extreme contagiousness, revealing that transmission requires prolonged and close contact. Multi-drug therapy, a breakthrough treatment, has revolutionised the management of leprosy, leading to its curability and prevention of disabilities.

Robben Island’s transition: From isolation to integration

The closure of the leprosy colony on Robben Island in 1931 signifies a pivotal moment in the medical landscape of leprosy. This marked a global shift in perceptions, advocating for improved medical care and the integration of individuals into society over isolation. Robben Island’s transition serves as a powerful reminder of the broader progress in dismantling the stigma associated with leprosy, emphasising a compassionate and medically informed approach.4

Stigmatisation in India: A comparative analysis

The stigmatisation of leprosy in India echoes the historical isolation policies of Robben Island. India’s historical connection with leprosy dates back to ancient texts, where myths and misconceptions abound. The deeply ingrained fear and cultural beliefs surrounding leprosy have perpetuated societal discrimination. Leprosy colonies were established, and sufferers faced marginalisation, loss of livelihood, and even abandonment due to societal ostracisation.5

Signs of leprosy were observed in the skeletal remains recovered from a Vedic burial site at Balathal, near Udaipur, Rajasthan, dating around 2000 BC. We have historical evidence that suggests the burial of leprosy patients during Vedic times.6

Till the early 20th century, the only known means of tackling leprosy was isolation. Robert Cochrane in Madras Presidency envisaged prevention by way of leprosy sanatoria, leprosy colonies, domestic isolation, night isolation of infectious patients outside the village, and sanatoria for leprosy-affected children. Leprosy patients were institutionalised together with other handicapped or marginalised people in various dharamshalas or leprosy asylums. It was believed that such isolation also ensured sexual segregation and prevented hereditary transmission of the disease. Till as late as the 1930s, leprosy patients practiced suicide, often with the aid of their relatives, through burning or burying alive, drowning, or jumping off cliffs.7

The modern Indian context: Progress and challenges

The global endorsement of Hansen’s suggestions on the separation of leprosy patients as a means of control came in 1897.8 In modern India, efforts to combat leprosy stigma have led to improvements in medical care and widespread awareness campaigns. Organisations such as The Leprosy Mission have played a pivotal role in educating the public and offering support. Despite these strides, challenges persist, impacting early diagnosis and treatment, particularly in remote areas. Initiatives such as the Leprosy Case Detection Campaign and integration into the general healthcare system highlight India’s evolving approach to leprosy management. The last Sunday of January or January 30th of every year also remembered as Martyrs’ Day, which marks the death anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, is observed as ‘Anti-Leprosy Day’ and messages regarding leprosy awareness are conveyed in every part of India.9

A shared journey: Similarities and lessons

The historical and medical trajectories of leprosy in Robben Island and India converge on the transformative power of knowledge, empathy, and societal change. Both experiences underscore the significance of accurate scientific information in dismantling stigma.

Thomas Bernard Fitzpatrick and Pathak have cited Atharvaveda and its mention of using Psoralea corylifolia (phototherapy) in leprosy. They have also mentioned the confusion between hypopigmented leprosy and vitiligo.10 This suggests how people in the past were not necessarily cruel for their unjust behaviour towards leprosy patients. Despite their best efforts, they were unable to find a cure. Those efforts were not futile as they subsequently led us to phototherapy. Isolation was the only viable option without any existing therapy, from the public health perspective. It is imperative to remember that we are talking of a period when even the causative organism was unclear.

The transition from isolation to integration witnessed both on Robben Island and in India, emphasises the importance of accessible healthcare and compassion in overcoming bias.

Moving forward with empathy and knowledge

Our visit to Robben Island provided a profound insight into the intertwined histories of leprosy, medical advancement, and societal transformation. The island’s leprosy colony and India’s experiences serve as poignant reminders of the power of education, medical progress, and compassion. As we envision the future, it is imperative to reinforce the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and to continue challenging stigma, advocating for accessible healthcare, and fostering empathy to create a world where leprosy patients are met with understanding rather than discrimination.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- 2015. International leprosy association - history of leprosy. Leprosyhistory.org; Available from: https://leprosyhistory.org/ [Last accessed in 2023 August 13]

- The place and space of illness: Climate and garden as metaphors in the robben island medical institutions. 1997. History of science, medicine and technology. (Unpublished) Available from: https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/4413/ [Last accessed in 2023 December 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2022. Robben island museum. Available from: https://www.robben-island.org.za/ [Last accessed in 2023 August 13]

- 1994. A history of the medical institutions on Robben Island, Cape Colony, 1846–1910. Available from: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/272392 [Last accessed in 2023 December 01]

- Leprosy stigma & the relevance of emergent therapeutic options. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Ancient skeletal evidence for leprosy in India (2000 BC) PloS one. 2009;4:e5669.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- IAL Textbook of Leprosy (3rd ed). India: Jaypee Brothers Medical; 2023.

- The first international leprosy conference, Berlin, 1897: The politics of segregation. Indian J Leprosy. 2004;76:51-70.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of India initiative against leprosy – We should be aware. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:3072-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Part IV: Basic considerations of the psoralens: Historical aspects of methoxsalen and other furocoumarins. J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:229-31.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]