Translate this page into:

Low-dose rituximab as an adjuvant therapy in pemphigus

Corresponding Author:

Jaya Gupta

M 79 Greater Kailash Part 1, New Delhi - 110 048

India

gptjaya@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Gupta J, Raval RC, Shah AN, Solanki RB, Patel DD, Shah KB, Badheka AD, Shah KB, Aggarwal NK, Ravishankar V. Low-dose rituximab as an adjuvant therapy in pemphigus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:317-325 |

Abstract

Background: Pemphigus is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease where systemic steroids and immunosuppressants are the mainstay of therapy, but long-term treatment with these agents is associated with many side effects. Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, in low doses has shown efficacy as an adjuvant to reduce the dose of steroids.Aim: To study the clinical efficacy and safety of low-dose rituximab as an adjuvant therapy in pemphigus.

Methods: Fifty patients with extensive pemphigus were selected, who either had recalcitrant pemphigus, were steroid dependent, had relapsed after pulse therapy, had anti-desmoglein levels >20, had contraindications to conventional treatment or wanted to avoid conventional treatment and its side effects. Two doses of rituximab (500 mg) were given 2 weeks apart and patients were regularly followed up every 2 weeks for 3 months and then monthly upto 2 years. Complete blood counts, liver function tests, renal function tests, skin biopsy, direct immunofluorescence and desmoglein levels were checked before and after rituximab administration. Pre-rituximab chest X-ray and electrocardiograph were also obtained.

Results: At 3 months, 41 (82%) patients showed complete remission. Nine (18%) patients had partial remission. After 6–12 months, 20 (40% of enrolled patients) continued to be in remission and were off all systemic therapy and the remaining 19 (38%) were continuing to take low doses of steroids with or without other adjuvant immunosuppressants and 2 (4%) had to be given another 2 doses of rituximab and subsequently could be managed with low-dose steroids. Of the 9 patients in partial remission at 3 months, after 6–12 months 5 (10% of the total) were completely off treatment and went into complete remission and 4 (8%) were on additional treatment out of which 2 (4%) had to be given 2 additional doses of rituximab and were in partial remission with low-dose therapy at the end of 12 months. One patient developed urticaria as a side effect. Another developed herpes zoster.

Conclusion: Our results show that low-dose rituximab is a well-tolerated and beneficial adjuvant therapy in recalcitrant pemphigus which helps reduce both the severity of disease as well as the dose of steroids and immunosuppressants.

Introduction

Pemphigus is a chronic autoimmune bullous dermatosis, histologically characterized by intra-epidermal blister formation and immunopathologically by the presence of bound and circulating autoantibodies directed against the intercellular adhesion proteins of cutaneous and/or mucosal epithelial cells.[1] The incidence varies from 0.09% to 1.8% in dermatology outpatients.[2],[3] It is mediated by pathogenic autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 1 and/or desmoglein 3.[4],[5],[6] Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common subtype, accounting for 75 to 92% of all pemphigus cases.[3],[7] Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy or long-term oral corticosteroids with or without adjuvant immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil have been used for severe cases of pemphigus in India.[1],[8] Though many treatment options are available, it still remains an unpredictable disease. The chronic immunosuppression resulting from treatment also increases the risk of infections and malignancy which ultimately lead to increased morbidity and mortality.[9] The challenge in pemphigus treatment, therefore, is to balance the risks of disease with risks of therapy. Thus, there is a constant search for newer and safer therapeutic modalities.

Rituximab is a chimeric human-mouse monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody. It is directed against CD20, a pan B-cell glycoprotein expressed on B lymphocytes from the pre-B cell through the preplasma-cell stage. Rituximab destroys B cells mainly through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity; other mechanisms include complement-mediated lysis, direct disruption of signaling pathways and triggering of apoptosis.[10] Rituximab is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (375 mg/m2 once a week; total duration varies with type of lymphoma) and for rheumatoid arthritis (2 doses of 1000 mg given 2 weeks apart and repeated after few months if required).[11],[12] It has several off-label uses too, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis and for autoimmune blistering disorders. The first blistering disease to respond to rituximab was paraneoplastic pemphigus with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[13],[14],[15] The most common regimen used is the lymphoma protocol.[16],[17],[18],[19] As pemphigus is not a malignant disease, a lower dose of rituximab (500 mg at 2 weeks interval) can suffice and such dosing is reported to have a better side effect profile.[20]

Our main aim was to assess the benefit of low-dose rituximab as an adjuvant therapy for pemphigus, particularly in cases difficult to treat conventionally, to study its clinical efficacy and safety.

Methods

Patients

Informed consent and permission from the ethics committee was taken. Fifty pemphigus patients, who were difficult to treat using conventional therapy, were enrolled and received injection rituximab 500 mg at 2 weeks intervals as an adjuvant to their existing treatment modalities between October 2012 and March 2014. Inclusion criteria included at least one of the following:

- Patients with recalcitrant pemphigus who had either failed to respond (i.e., developed fresh crops of new lesions or had extension of old lesions), or responded but with frequent recurrences, while on long-term high dose oral prednisolone (40–60 mg/day for 12 weeks), with or without additional immunosuppressive therapy

- Patients with recurrent relapse after dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone-azathioprine pulse therapy, (i.e., fresh crop of lesions or extension of old lesions) after completing 9 cycles of dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide or dexamethasone-azathioprine pulse therapy

- Patients with desmoglein antibody (anti-desmoglein-1 and/or anti-desmoglein-3) levels >20

- Steroid dependence, i.e., patients being treated with prednisone 30–40 mg/day for more than 1 year and in whom lowering of dose resulted in a fresh crop of lesions

- Contraindications to the use of conventional therapy

- Unwillingness to continue conventional therapies.

Exclusion criteria included patients with pregnancy, breastfeeding, active hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, widespread infections and cardiac disease.

Diagnoses were confirmed by classical clinical presentation, histology, direct immunofluorescence and ELISA assays of antibodies to desmoglein 1 or 3.

All patients had been treated in the past for periods varying between 5 months and 10 years with some or all conventional regimens such as prednisolone 1–1.5 mg/kg/day, cyclophosphamide 1–2 mg/kg/day, azathioprine 1–2 mg/kg/day and dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulses or dexamethasone-azathioprine pulses.

Pretreatment workup

Skin biopsies from all patients were submitted for histological assessment using hematoxylin-eosin staining. A perilesional biopsy was also sent for direct immunofluorescence. Serum anti-desmoglein antibody levels were determined before infusion and repeated 1 month after infusion and subsequently every 3 months for upto 2 years. Pretreatment workup included a complete hemogram, liver function tests, renal function tests, fasting and postprandial blood sugar levels, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, Mantoux test, screening for viral infections including Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus-1 and human immunodeficiency virus-2, and serum IgG.

Treatment protocol

Patients were premedicated with hydrocortisone (100 mg), pheniramine maleate (8 mg), and paracetamol (1 g) intravenously 30 minutes prior to infusion. On the day of infusion, antibiotic coverage was given with two doses of injection ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously 12 hours apart.

Injection rituximab (500 mg) in 500 ml of normal saline solution was given over 6 hours and a second dose was given after 2 weeks. Vitals were monitored every 15 minutes and patients were watched for hypotension, nausea, headache, chills, fever and rashes. Two additional doses were given 6 months after the first treatment in case of failure (non-healing old lesions, appearance of new lesions which did not heal within 2 weeks and consistently positive anti-desmoglein-1 and anti-desmoglein-3 levels).

Monitoring and follow up

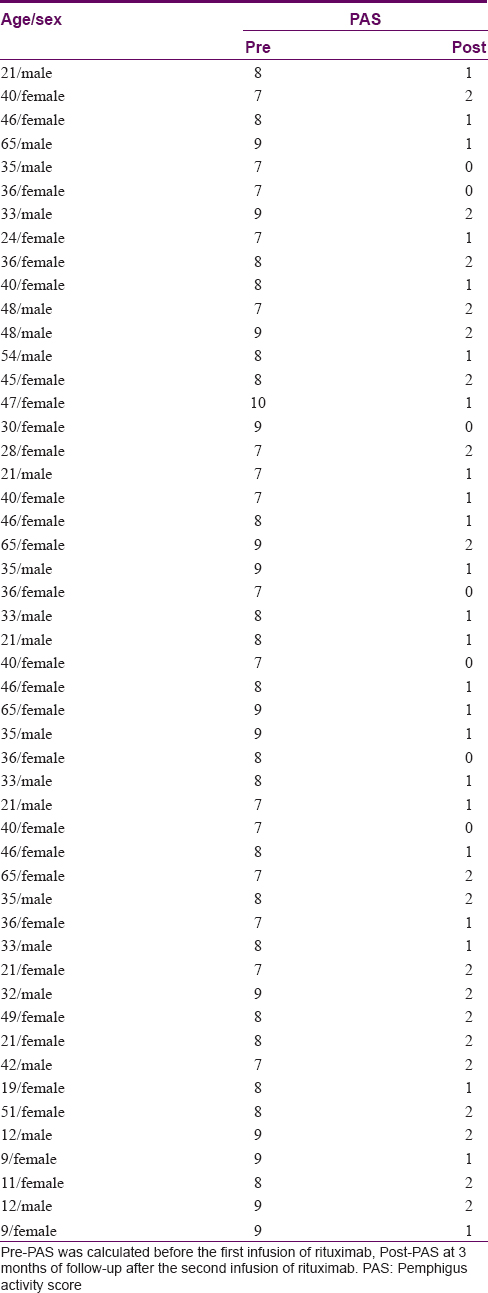

To determine the response, we calculated the pemphigus activity severity score published by Herbst and Bystryn and used by Londhe et al.[21],[22] It was calculated pre-infusion and at 3 months, post 2nd infusion.

Patients were followed up every 2 weeks for 3 months after the second infusion followed by monthly follow-up for up to 2 years. Endpoints were defined as complete remission off therapy (no lesions and no therapy), complete remission on treatment with low-dose steroids or some immunosuppressant, partial remission (1-2 lesions/<2% body area involvement) off therapy and on therapy. Follow-up duration of our patients after the second dose of rituximab ranged from 12–25 months with a median of 17 months.

Results

Patient characteristics

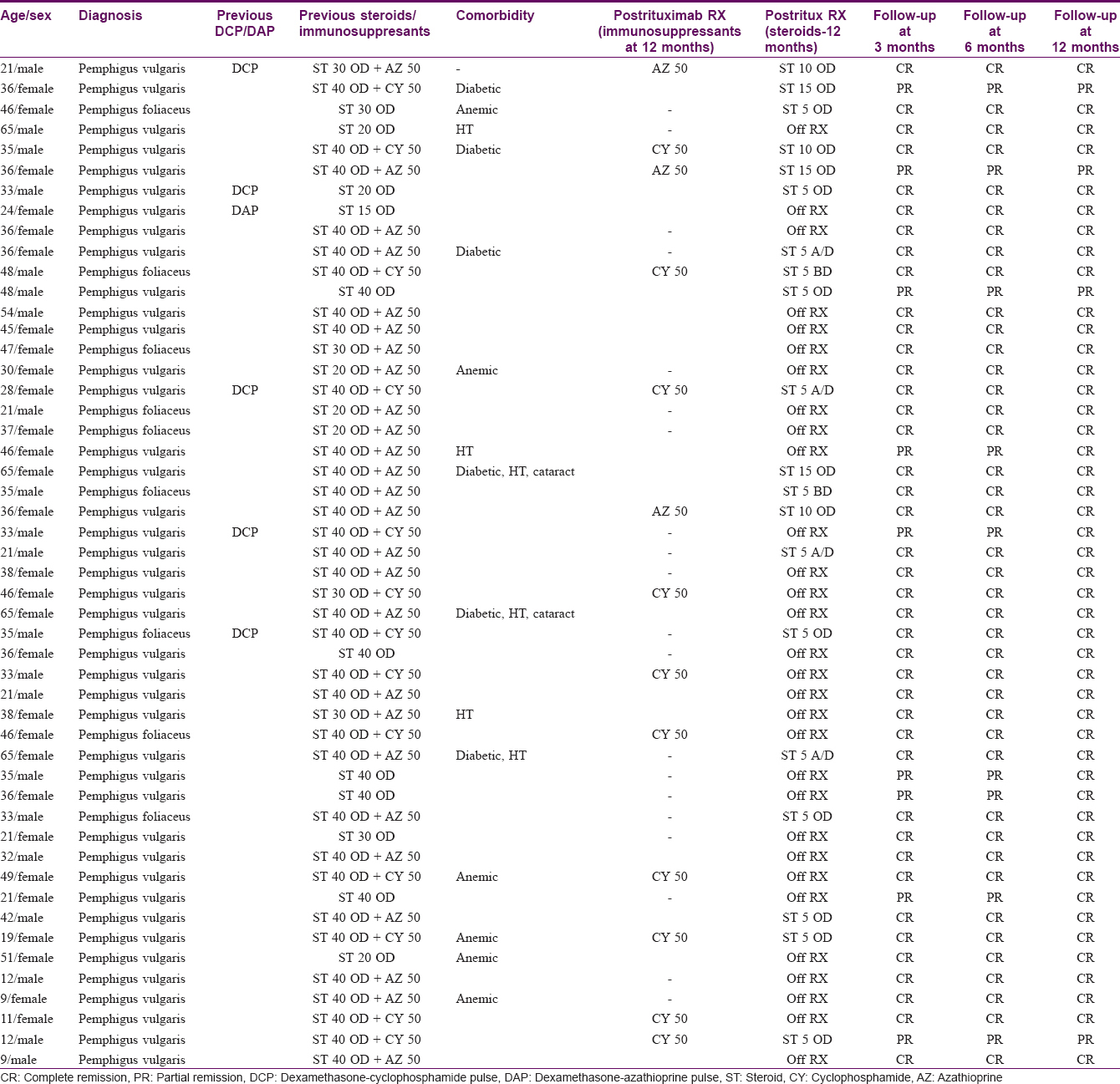

Fifty patients were included in this prospective study; 9 had pemphigus foliaceus and 41 had pemphigus vulgaris. Our study subjects included 30 females and 20 males aged between 9 to 65 years (median 38 years, mean 35.7 years). The use of rituximab in the pediatric age group is restricted, mainly because of limited experience. However, some studies have been published in this regard.[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29] Our series of patients included 5 pediatric patients (who were not responding to any other kind of therapy). The duration of pemphigus in our patients ranged from 6 months to 10 years (median 2 years, mean 1.5 years). Of all patients, 26 had steroid dependence (were being treated with prednisone 30–40 mg/day for more than 1 year and dose reduction resulted in fresh lesions); 12 patients were refractory to conventional treatment (6 had recalcitrant pemphigus and 6 had relapsed after receiving 9 cycles of dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse/dexamethasone-azathioprine pulse therapy); 5 had developed morbidity due to medication and hence had contraindications to the continued use of conventional therapy; and, 7 were unwilling to continue with conventional therapies due to their side effects and wanted to try new medication. Other comorbidities are mentioned in [Table - 1].

The interval between two infusions was 2 weeks in 47 patients and 3 weeks in 3 patients (one developed herpes zoster and the other two came late for follow-up).

Clinical efficacy and relapse rate of rituximab on pemphigus

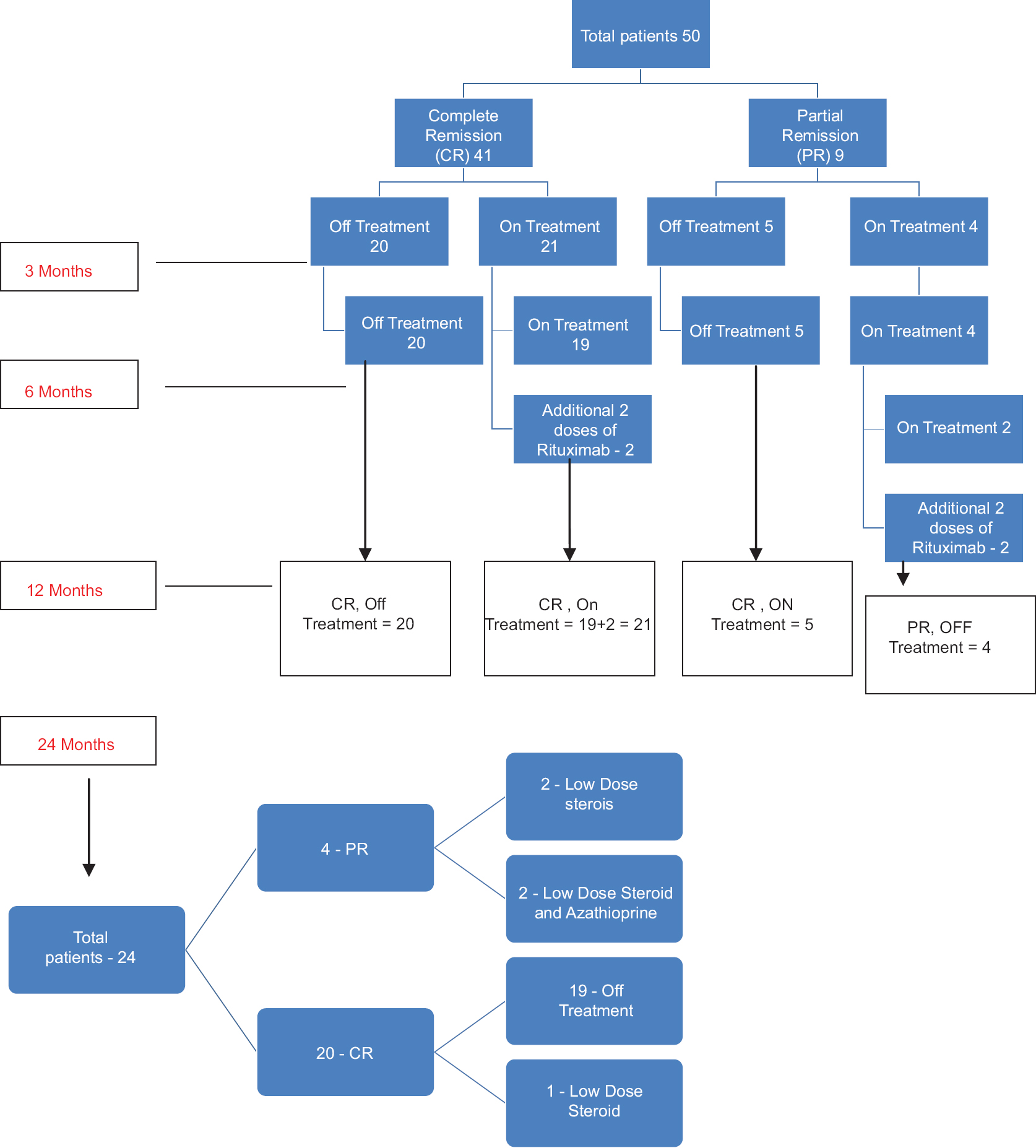

Forty-one (82%) of 50 patients had a complete remission either on or off treatment and 9 (18%) patients showed only partial remission at the end of 3 months [Figure - 1], [Figure - 2], [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4], [Figure - 5], [Figure - 6].

|

| Figure 1: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

|

| Figure 2: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

|

| Figure 3: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

|

| Figure 4: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

|

| Figure 5: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

|

| Figure 6: Image of a patient before receiving rituximab and 3 months after 2nd infusion |

After 6 months, 20 of 50 enrolled patients (40%) maintained complete remission and were off all systemic therapy, 19 (38%) patients were continuing with low dose steroids (prednisolone 5–20 mg/day) with or without immunosuppressants and 2 (4%) had a relapse and had to be given additional 2 doses of rituximab. Of 9 patients in partial remission after 6 months, 5 (10%) were completely off treatment and went into complete remission and 4 (8%) were on additional treatment out of which 2 (4%) had a relapse and had to be given 2 additional doses of rituximab [Figure - 7]. Thus, overall, 8% had relapsed (patients with persistent new lesions not healing with low dose steroids/immunosuppressants and topical treatment in 2 weeks) but were successfully treated with 2 extra doses of rituximab. They all achieved remission within 52 weeks post-treatment [Figure - 7].

|

| Figure 7: Flow chart representing the response to rituximab. CR: Complete remission, PR: Partial remission, On Rx: On low dose steroids and/or other immunosuppressants, Off Rx = Not on oral steroids or other immunosuppressants |

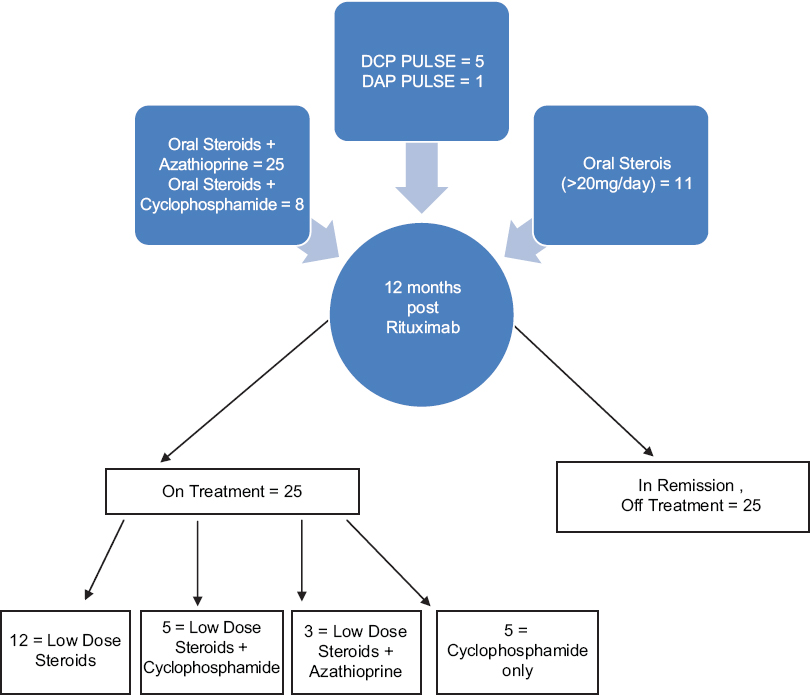

At the end of 12 months, 25 out of 50 patients were still on therapy with immunosuppressants and/or steroids. Of these, 12 were on only low-dose steroids (prednisolone 5–20 mg/day) [Figure - 8].

|

| Figure 8: Patients on additional treatment besides rituximab at 12 months. High dose steroids ≥30 mg/day, Low dose steroids ≤20 mg/day |

Twenty-four patients had 24 months follow-up. At the end of 24 months, 20 (83.3%) were in complete remission with only one of them on treatment and 4 (16%) were in partial remission on treatment (two with low-dose steroid alone and two with low-dose steroid and azathioprine) [Figure - 7].

Serological evaluation of antidesmoglein-1 and antidesmoglein-3 and pemphigus activity score severity score evaluation

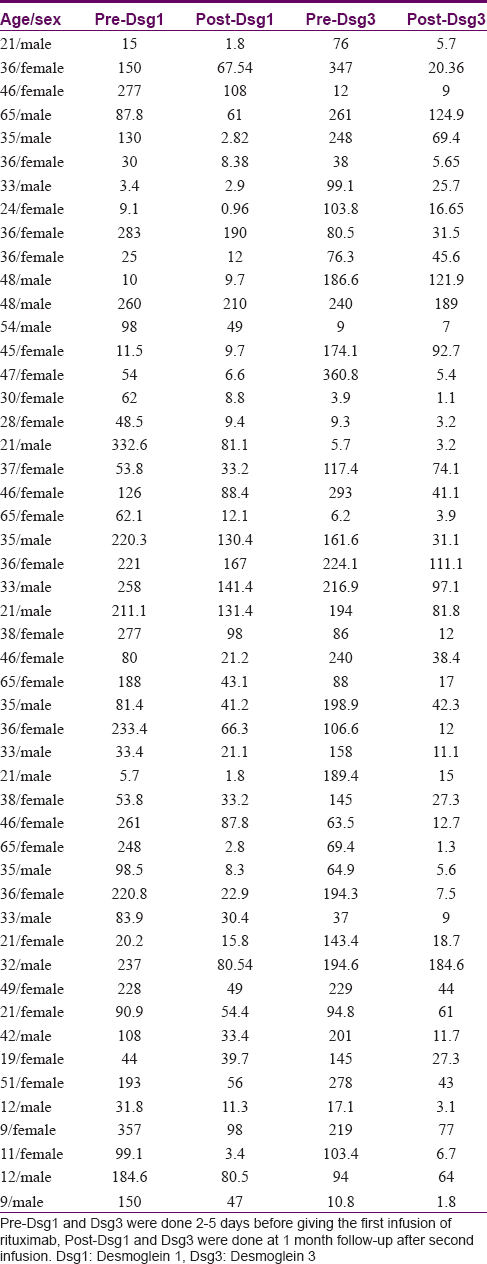

The mean pre-treatment anti-desmoglein-1 level was 132.9 and post-treatment, 1 month after the second dose of rituximab, it fell to 51.6. The mean pre-treatment anti-desmoglein-3 level was 138.3, which dropped to 39.48, a month after the second dose [Table - 2].

The mean pre-treatment pemphigus activity score was 7.98 (range 3–9), which reduced to 1.24 (0–6) 3 months after the second dose [Table - 3]. The maximum possible value of the severity score used was 10; extent of disease received 0 to 4 points and intensity of therapy received 0 to 6 points.[21]

Adverse effects

One patient developed chills, one had urticaria following infusion, one had decreased blood pressure and one developed herpes zoster which was managed without any complication. No major side effects were encountered.

Discussion

The optimal dosage of rituximab for pemphigus has not been clearly defined. A recent study using modified lymphoma protocol by Londhe et al. showed 79% complete remission in 9/19 in whom all other treatment could be stopped and 10 remained on minimal dose of steroids and immunosuppresants at 9 months.[22] In a review by Zakka et al., 180 patients were treated with the lymphoma protocol and 92 patients were treated with the rheumatoid arthritis protocol and complete remission occurred in 66.7% patients on lymphoma protocol and 75% in rheumatoid protocol.[30] Several cases have been published using both lymphoma protocol and rheumatoid protocol. Currently, there is no consensus for the dosing of rituximab in pemphigus; a study by Kanwar et al., comparing 2 doses of 1000 mg given 2 weeks apart and 2 doses of 500 mg given 2 weeks apart with 11 patients in each group, showed that there was a difference in anti-desmoglein levels and a higher relapse rate with lower dosing, but no statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes or relapse rates between the two regimens.[31]

Our prospective open study demonstrates success with low-dose rituximab in a series of 50 patients. The dose of 500 mg, 2 weeks apart, has been used before.[20],[31] It is 39% and 50% of the doses used in hematology and rheumatology, respectively, thus cutting the cost of the treatment to half or less. Horváth et al. demonstrated complete remission in 52% patients (median follow-up 22 months) with the same protocol as used in our study.[20] In comparison, we saw complete remission (either on or off other treatment) in 82% of our patients within 3 months of adjuvant rituximab therapy. At the end of 1 year, 25 (50%) of our patients were in complete remission off all treatment, while the remaining 25 continued to be on additional low dose steroids and/or immunosuppresants [Figure - 8], with no more relapses till date minimum 12 months follow-up. Thus, we achieved a success rate higher than that reported in the existing studies with any of the established protocols for other conditions. The variation in results and findings could be due to different genetic makeup of our patients which contributed to their requirement of lower doses.

There are no double-blinded, randomized trials available comparing the conventional dexmethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy with rituximab. Indian patients usually show a good response to conventional dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse and oral corticosteroids. However, some patients are resistant to conventional therapy or have contraindications for their use or become steroid-dependent. After a mean duration of 12 months of follow-up, all our patients had responded, 25 of these patients were not receiving any systemic therapy. The four patients who relapsed showed a correlation of anti-desmoglein-1 and anti-desmoglein-3 titers with disease activity. Among the patients who responded initially, 5 had earlier been treated with dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse and 43 had been given high-dose (>30 mg/day) steroids. Overall, treatment with rituximab resulted both in major clinical improvement and a large decrease in the doses of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants; 25 patients who were earlier on daily steroids could be weaned off them. For 20 patients who continued to need daily steroids, the mean daily requirement fell from 35 mg to 15 mg and in 26 out of 39 patients needing other immunosuppressants at the start of the study, they could be stopped.

In the majority cases of pemphigus vulgaris (37 out of 41), disease severity correlated with anti-desmoglein-3 levels. There was a 72.1% fall in the mean anti-desmoglein-3 level at the end of 1 month except some which remained positive immediately post-treatment [Table - 2] and most of them required additional low-dose steroid and immunosuppressants. The mean pemphigus activity score fell from 7.98 to 1.04 at the end of 3 months which is similar to what was seen in the study by Londhe et al. (5.58 to 2.04).[29]

The use of rituximab is associated with adverse effects. However, as observed in our study, using low doses helped to reduce the side effects. The adverse effects can be immediate: infusion-related - such as allergic responses, immediate cardiac effects, pulmonary embolism; or late ones like severe infections (10%) such as fatal septicemias seen in the study by Joly et al.[32] In our study, only one patient developed mild infusion reaction during the first infusion, subsequent infusions being uneventful. These reactions tend to resolve upon slowing infusion rates or addition of corticosteroids, antipyretics and antihistamines and do not recur in subsequent infusions.[33] Only one patient (2%) developed herpes zoster. None of our patients exhibited late serious side effects. There were no fatalities in our study. No patient experienced a serious adverse event, namely pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis. Other late adverse effects have been described including late-onset neutropenia reported 3–23 weeks after rituximab infusion.[34],[35] None of our patients developed this side effect.

Conclusion

Low-dose rituximab can induce a prolonged clinical remission in pemphigus with minimal side effects. It is a fairly well-tolerated adjuvant therapy which helps to reduce both the severity of disease as well as the dose of steroids and immunosuppressants. As the optimal dose of rituximab is not known, further randomized trials are needed to determine the dose and they need to take cost-effectiveness ratios into account. This is especially applicable to a resource-poor setting like India. Factors limiting the use of rituximab include its high cost and limited knowledge of long-term adverse effects. Once these hurdles are overcome, it can be considered an adjuvant for the treatment of pemphigus, thus reducing the use of other immunosuppressants and thereby reducing the burden of their long-term use including adverse effects, continuous hospitalizations and lowered quality of life.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. | Sacchidanand S. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. Mumbai: Bhalani Book Depot; 2008. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Mascarenhas MF, Hede RV, Shukla P, Nadkarni NS, Rege VL. Pemphigus in Goa. J Indian Med Assoc 1994;92:342-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Kanwar AJ, Ajith AC, Narang T. Pemphigus in North India. J Cutan Med Surg 2006;10:21-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Stanley JR. Pemphigus and pemphigoid as paradigms of organ-specific, autoantibody-mediated diseases. J Clin Invest 1989;83:1443-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Stanley JR. Cell adhesion molecules as targets of autoantibodies in pemphigus and pemphigoid, bullous diseases due to defective epidermal cell adhesion. Adv Immunol 1993;53:291-325. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Amagai M, Klaus-Kovtun V, Stanley JR. Autoantibodies against a novel epithelial cadherin in pemphigus vulgaris, a disease of cell adhesion. Cell 1991;67:869-77. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Sehgal VN. Pemphigus in India. A note. Indian J Dermatol 1972;18:5-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy in pemphigus. Int J Dermatol 1990;29:371-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Bystryn JC, Steinman NM. The adjuvant therapy of pemphigus. An update. Arch Dermatol 1996;132:203-12. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Schmidt E, Bröcker EB, Goebeler M. Rituximab in treatment-resistant autoimmune blistering skin disorders. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2008;34:56-64. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Furst DE, Keystone EC, Fleischmann R, Mease P, Breedveld FC, Smolen JS, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2009. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69 Suppl 1:i2-29. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Keystone E, Fleischmann R, Emery P, Furst DE, van Vollenhoven R, Bathon J, et al. Safety and efficacy of additional courses of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: An open-label extension analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3896-908. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Borradori L, Lombardi T, Samson J, Girardet C, Saurat JH, Hügli A. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) for refractory erosive stomatitis secondary to CD20(+) follicular lymphoma-associated paraneoplastic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:269-72. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Heizmann M, Itin P, Wernli M, Borradori L, Bargetzi MJ. Successful treatment of paraneoplastic pemphigus in follicular NHL with rituximab: Report of a case and review of treatment for paraneoplastic pemphigus in NHL and CLL. Am J Hematol 2001;66:142-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Schadlow MB, Anhalt GJ, Sinha AA. Using rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) in a patient with paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Drugs Dermatol 2003;2:564-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Maloney DG, Liles TM, Czerwinski DK, Waldichuk C, Rosenberg J, Grillo-Lopez A, et al. Phase I clinical trial using escalating single-dose infusion of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC-C2B8) in patients with recurrent B-cell lymphoma. Blood 1994;84:2457-66. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, et al. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood 1997;90:2188-95. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Remuzzi G. Titrating rituximab to circulating B cells to optimize lymphocytolytic therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:932-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Looney RJ, Anolik JH, Campbell D, Felgar RE, Young F, Arend LJ, et al. B cell depletion as a novel treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus: A phase I/II dose-escalation trial of rituximab. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2580-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Horváth B, Huizinga J, Pas HH, Mulder AB, Jonkman MF. Low-dose rituximab is effective in pemphigus. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:405-12. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Herbst A, Bystryn JC. Patterns of remission in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:422-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Londhe PJ, Kalyanpad Y, Khopkar US. Intermediate doses of rituximab used as adjuvant therapy in refractory pemphigus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014;80:300-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Kanwar AJ, Vinay K. Rituximab in pemphigus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:671-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Kanwar AJ, Tsuruta D, Vinay K, Koga H, Ishii N, Dainichi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in Indian pemphigus patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e17-23. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Reguiai Z, Tabary T, Maizières M, Bernard P. Rituximab treatment of severe pemphigus: Long-term results including immunologic follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:623-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Connelly EA, Aber C, Kleiner G, Nousari C, Charles C, Schachner LA. Generalized erythrodermic pemphigus foliaceus in a child and its successful response to rituximab treatment. Pediatr Dermatol 2007;24:172-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Kong HH, Prose NS, Ware RE, Hall RP 3rd. Successful treatment of refractory childhood pemphgus vulgaris with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab). Pediatr Dermatol 2005;22:461-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Schmidt E, Herzog S, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D, Goebeler M. Long-standing remission of recalcitrant juvenile pemphigus vulgaris after adjuvant therapy with rituximab. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:449-51. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Fuertes I, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr., Iranzo P. Rituximab in childhood pemphigus vulgaris: A long-term follow-up case and review of the literature. Dermatology 2010;221:13-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Zakka LR, Shetty SS, Ahmed AR. Rituximab in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2012;2:17. [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Kanwar AJ, Vinay K, Sawatkar GU, Dogra S, Minz RW, Shear NH, et al. Clinical and immunological outcomes of high- and low-dose rituximab treatments in patients with pemphigus: A randomized, comparative, observer-blinded study. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:1341-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 32. | Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, D'Incan M, Gilbert D, Jacquot S, et al. A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus. N Engl J Med 2007;357:545-52. [Google Scholar] |

| 33. | Vogel WH. Infusion reactions: Diagnosis, assessment, and management. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:E10-21. [Google Scholar] |

| 34. | Voog E, Morschhauser F, Solal-Cé ligny P. Neutropenia in patients treated with rituximab. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2691-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 35. | Wolach O, Bairey O, Lahav M. Late-onset neutropenia after rituximab treatment: Case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89:308-18. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

7,895

PDF downloads

3,307