Translate this page into:

Management of psoriatic arthritis

2 Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Correspondence Address:

Aman Sharma

Rheumatology Devision, Department of Internal Medicine, PGIMER, Chandigarh

India

| How to cite this article: Sharma A, Dogra S. Management of psoriatic arthritis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;76:645-651 |

Abstract

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that can be progressive and may be associated with permanent joint damage and disability. Early identification of PsA will enable these patients with progressive disease to be treated early and aggressively. Due to lack of consistent diagnostic or classification criteria in the past, PsA was considered as uncommon. Overall it affects 6-10% of all psoriasis patients during the course of their disease. Both dermatologists and rheumatologists should be involved in the diagnosis and management of this disorder. Interest in PsA has greatly enhanced over the past several years due to many factors including a better understanding of disease mechanisms, improved investigational tools, better clinical trial design and perhaps most importantly, the availability of newer therapeutic agents. Mild forms of PsA can initially be treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAID). In acute as well as oligo- to polyarticular joint involvement, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD) are indicated for PsA. The biologics particularly tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF- a) antagonists are gaining increasing significance as second-line therapy. Treatment choice should also take into consideration the extent of skin involvement.Introduction

The first description of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was given in the early 19th century but it was identified as a distinct entity by the American Rheumatology Association only in 1964. [1],[2] The prevalence of arthritis in psoriasis patients has varied widely from 6% to 42%. [3] In an Indian study of 530 patients with psoriasis, 48 had arthralgias and 7 had deforming arthritis. [4] Five different types of clinical patterns have been described by Moll and Wright. [5] These are (a) classical PsA confined to the distal interphalangeal joints (5%), (b) arthritis mutilans (5%), (c) symmetrical polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis (RA), (d) asymmetrical oligoarthritis (70%) and (e) spondyloarthropathy (15%). In a North Indian study of 20 patients based upon these criteria, four of the five varieties were described and arthritis mutilans was not seen. [6] In another study of 116 patients with PsA from south India, symmetrical polyarthritis was the most common subtype seen in almost half of the patients. [7] Various other criteria have also been proposed by Bennett, [8] Vasey and Espinoza, [9] modified McGonagle criteria, [10] modified European spondyloarthropathy criteria [11] and Fournie criteria; [12] but the classification of psoriatic arthritis (CASPAR) criteria [13] is likely to become the standard tool for establishing case definitions for clinical studies. According to the CASPAR criteria, presence of three of the following five features in a patient with inflammatory articular disease (joint, spine or entheses) are required to make a diagnosis of PsA (a) current psoriasis or personal history of psoriasis or family history of psoriasis, (b) psoriatic nail dystrophy including onychomycosis, pitting and hyperkeratosis, (c) a negative test for rheumatoid factor, (d) current or past history of dactylitis and (e) radiological evidence of juxta articular new bone formation.

The predominant clinical manifestations of PsA include peripheral arthritis, axial disease, dactylitis and enthesitis, besides the skin and nail psoriasis. [14] Effective drug therapies of PsA are directed towards each of these manifestations. In addition to the drug therapy, various non-pharmacological therapeutic interventions like patient education, physical and occupation therapy and interdisciplinary cooperation between the dermatologist, rheumatologist and physical and occupation therapist are very important. Enthesopathy, a major feature of PsA, is often an underdiagnosed entity. Ultrasonography can detect a significantly higher incidence of entheseal abnormalities even in the absence of clinical symptoms of arthropathy. [15] The primary focus of various groups studying the role of imaging is on enthesis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography provide evidence of pathological change at the enthesis in PsA. The role of newer imaging modalities, such as ultra-short echo time (UTE) MRI, is promising but remains to be fully elucidated.

PsA can produce erosive joint disease and impairment in the quality of life comparable to that produced by RA. [15],[16] Clinical features that distinguish PsA from RA include distal interphalangeal joint involvement, asymmetrical joint involvement, oligoarticular disease pattern, enthesitis and relative lack of rheumatoid factor positivity. [17] Just like in RA, the rapid control of signs and symptoms along with a delay or prevention of radiological joint damage and maintaining good functional capacity is the aim of therapy. It has been shown that early and aggressive control of disease activity in RA leads to good outcome. [18] Similar results can be expected from early treatment in patients with moderate to severe PsA. The risk factors for severe disease include polyarticular disease, elevated acute phase reactants, evidence of disability and erosive joint disease, as well as demonstration of lack of response to initial therapeutic agents. [19] There is a need for increase in awareness about PsA in patients and dermatologists for an early and accurate diagnosis of PsA. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) has developed simple screening tools, which can be used by dermatologists and other clinicians to screen for the presence of PsA in their patient population. [20] Ideally, the dermatologist and rheumatologist should work as a team to supervise all aspects of the patient′s disease.

The type of therapy employed for PsA depends upon the severity of joint involvement at the time of presentation. Mild joint inflammation may be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Severe cases of PsA that present with polyarticular joint involvement or destructive progression require early administration of many of the traditional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Newer biologic agents have shown promise in treating PsA refractory to the traditional drug therapies. Long-term, perhaps lifelong, treatment with the DMARDs is required in patients with active disease.

Traditional Therapy

Traditional treatment of PsA includes NSAIDs and traditional DMARDs. NSAIDs may produce some symptomatic relief but do not have any effect on the progression of joint disease and some of the NSAIDs can worsen the skin disease. [21] The choice of NSAIDs depends upon the efficacy, safety, convenience and cost. COX inhibitors should be avoided in patients with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Routine co-prescription of antacids is not required unless there are risk factors for NSAID-induced gastrointestinal (GI) events like age more than 65 years, history of peptic ulcer disease or bleeding from the GI tract, concomitant use of corticosteroids (CS). Traditional DMARD therapies have not been studied very extensively. The data are derived from small, poorly controlled trials which did not use any validated outcome measures. [22]

Corticosteroids

Low dose CS therapy has been shown to slow the radiological progression in RA but such studies have not been done in PsA. [23] Intraarticular CS can be given in oligoarticular disease or polyarticular disease with one or two active joints. CS should be used very judiciously because of the risk of flare up of pustular psoriasis on stopping them.

Sulphasalazine

Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is used to treat inflammatory bowel disease and RA. The exact mechanism of action of sulfasalazine is unknown, though it is thought to function as an anti-inflammatory agent. The efficacy of SSZ in PsA has been evaluated in a number of studies. In a large placebo-controlled study of 221 patients with active disease, there was a significant improvement in the PsA response criteria (PsARC) but there was no significant improvement in the secondary outcome measures and lab parameters. These included enthesitis, dactylitis and spondylitis. [24] The PsARC took into account the number of swollen and tender joints and patients′ and physicians′ global assessment. No useful conclusion could be drawn from other studies comprising of small number of patients. There have been high drop-out rates and the most commonly reported side effects are rash and GI intolerance. The benefit of SSZ is usually confined to peripheral disease with no significant effect on axial disease. It is usually started at a low dose of 500 mg twice a day and the dose is increased weekly by 500 mg. The usual adult dose is 2-3 g/day.

Methotrexate

The first randomized controlled trial (RCT) showing the efficacy of methotrexate (MTX) in PsA was published in 1964. [25] The other RCT published was not powered and used only low dose MTX. Few uncontrolled case series have demonstrated its efficacy in PsA. [26],[27]

MTX is generally given as a single weekly dose. It is usually started at a low dose of 7.5 mg/week and is gradually increased to 20 and 25 mg/week. In a Cochrane review published in 1999 on the efficacy of SSZ, auranofin, etretinate, fumaric acid, intramuscular gold, azathioprine and MTX in PsA, it was concluded that parenteral high dose MTX and SSZ are the only two agents with well-demonstrated efficacy in PsA. [28]

All dosing schedules are adjusted according to the individual patient to achieve maximum disease control and to minimize the side effects. Folic acid should be supplemented to decrease the MTX toxicity. The usual dose of folic acid is 1-5 mg/day except on the day of administering MTX. [29]

Minor toxicities of MTX include nausea, anorexia, stomatitis, and fatigue. The major toxicities are myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and pulmonary fibrosis. MTX is teratogenic and should be stopped by both male and female patients, 3 months prior to conception. The risk factors for hepatotoxicity are history of or current greater than moderate alcohol consumption, persistent abnormal liver chemistry study findings, history of liver disease including chronic hepatitis B or C, family history of inheritable liver disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, history of significant exposure to hepatotoxic drugs and hyperlipidemia. [30] MTX toxicity in psoriatic disease has been the focus of discussion and debate. In a study aimed to assess the prevalence of hepatic fibrosis in both psoriasis and PsA patients on long-term MTX therapy, a prospective study of 54 patients showed that despite other risk factors for NASH (Non alcoholic steatohepatitis), monitoring for hepatic fibrosis using serial liver function and American college of rheumatology (ACR) guidelines tests alone as in RA appeared safe in psoriasis and PsA. Liver biopsy should be considered to assess the liver if liver function tests (LFT) are persistently elevated. [31]

In an Indian study of 33 patients of PsA treated with MTX, 39.5% had complete remission, 54.5% had partial remission and 6% had no response according to the American rheumatism association (ARA) criteria. The mean dose of MTX was 7.8 mg/week. [32] No significant side effects requiring discontinuation of therapy was seen.

Cyclosporine A

It acts by inhibiting the first phase of T-cell activation. It has been shown to be very effective for skin involvement by the disease but its role in the treatment of PsA has not been evaluated extensively barring a few open label studies. [33] The initial daily dose of cyclosporine A (CSA) is 2.5-3 mg/kg in divided doses. [29] The main side effects of cyclosporine are nephrotoxicity and hypertension. There is an increased risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas especially in patients with more than 200 psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatments. [34] Combination therapy with MTX in patients with disease refractory to MTX monotherapy was shown to produce improvement in psoriasis area and severity score (PASI) and synovial ultrasound score. [35] It can also cause side effects like hypertrichosis, headache, pseudotumor cerebri and gingival hypertrophy.

Leflunomide

Leflunomide is a a pyrimidine antagonist. Its efficacy in PsA was studied in 188 patients. At a dose of 20 mg/day, the PsARC response was achieved in 59% of leflunomide-treated patients compared with 29.7% of placebo-treated patients. [36] The usual adult dose is 100 mg/day for 3 days, followed by 20 mg/day.

The main side effects are GI irritation (diarrhea, nausea, dyspepsia), but also include elevated liver enzymes, leukopenia, drug eruption, headache, increased risk of infections. [37] It is a highly teratogenic drug and is contraindicated in pregnancy and women of childbearing potential not using reliable contraceptive methods. Women should not become pregnant for 2 years after the cessation of therapy or should undergo a rapid wash-out procedure with cholestyramine. Men wishing to father a child should discontinue leflunomide and should also undergo the wash-out procedure.

Retinoic acid derivatives and PUVA are effective in severe skin disease. In a study of PUVA in 27 patients with PsA, published in 1979, it was shown that aggressive therapy can improve PsA in a subgroup of patients with nonspondylitic disease. [38]

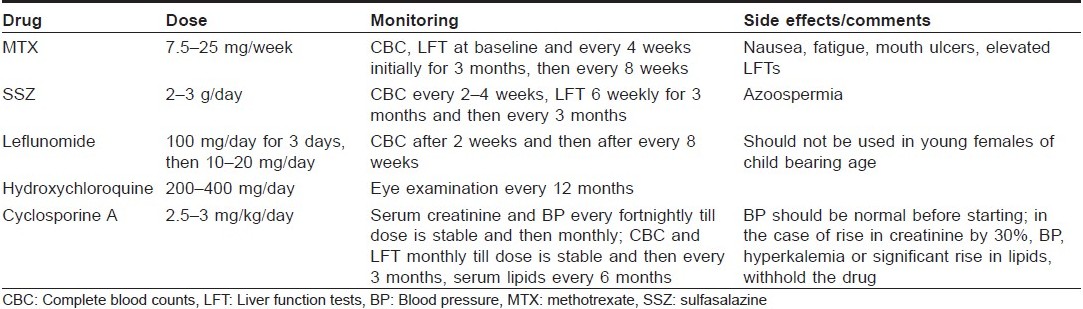

The other DMARDs used in the management of PsA include mycophenolate mofetil, [39] azathioprine, [40] antimalarials, [41] gold, [42],[43] and penicillamine. There is concern regarding the flare up of psoriasis with antimalarials but it has not been demonstrated in large studies. The dosing schedule, side effects and the monitoring required during use of these drugs are given in [Table - 1].

Biologic Therapies

The biologics currently approved for the treatment of PsA are antitumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF-α) compounds, etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), and adalimumab (Humira). Etanercept and infliximab are available in India. Recent trials with the T-cell modulating agents, alefacept and efalizumab, have been completed. A pilot study with abatacept in PsA is also being completed.

Etanercept

It is a recombinant human soluble TNF-α receptor antagonists given in a dose of 50 mg/week as 25 mg twice a week. In the placebo-controlled etanercept trial in PsA, ACR 20 response was achieved by 59% in the etanercept group versus 15% in the placebo group. [44] A recent study compared the effect of etanercept given 50 mg twice weekly for 12 weeks, followed by 50 mg weekly, with that of a dosage of 50 mg weekly in 752 patients. A composite joint score, the PsARC, showed similar improvement in both the groups. [45]

Infliximab

It is a chimeric monoclonal anti-TNF-α antibody approved for the treatment of PsA. A phase 3 study of infliximab in 200 PsA patients (IMPACT II) showed significant benefit. [46] Dactylitis and enthesitis decreased significantly and there was an inhibition of radiological disease progression at 24 weeks in the infliximab group. [47] Infliximab is given at a dose of 3 mg/kg as an infusion over 2 hours on 0, 2, and 6 weeks, and then every 2 months.

Adalimumab

This is a fully human anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody administered subcutaneously, 40 mg, every other week or weekly. New anti-TNF-α agents being developed for use in PsA are certolizumab pegol and golimumab.

Other biologic agents

Alefacept is a fully human fusion protein that blocks the interaction between leukocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-3 on the antigen-presenting cell and CD2 on the T cell, or by attracting natural killer lymphocytes to interact with CD2 cell to yield apoptosis of the particular T cell clones. [48] A phase 2 controlled trial of alefacept in PsA showed that 54% of patients in alefacept and MTX combination group had an ACR 20 response as compared to 23% in the MTX alone group. [49]

Efalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody to the CD11 subunit of LFA-1 on T cells. Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) is a recombinant human fusion protein that binds to the CD80/86 receptor on an antigen presenting cell, blocking the second signal activation of the CD28 receptor on the T cell. Ustekinumab, an IL12/23 inhibitor, has also shown efficacy in a preliminary study in PsA. [50]

Anakinra, an IL 1 inhibitor, has not shown significant effect. [51] B cell depletion therapy with Rituximab is being evaluated in PsA. If approved for use in PsA, it would have the advantage of no risk of tuberculosis (TB) in endemic countries . Tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody to IL6, has also shown benefit in PsA. [52]

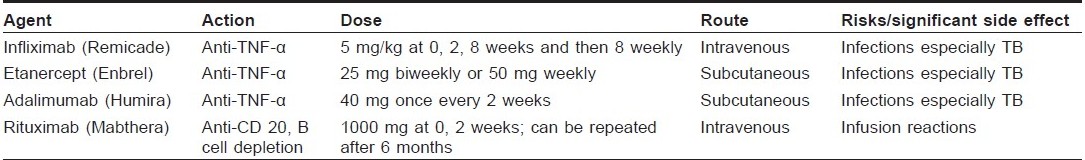

The mechanism of action, dosing schedule and major risks with the biologic therapies are given in [Table - 2].

Investigations before starting tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

Indian rheumatology association guidelines for the management of RA in adults recommend hemogram, biochemistry to include liver and renal function tests, hepatitis B and C serology, routine urine microscopy, chest X-ray and Mantoux test before starting TNF-α inhibitors. It is recommended that all the patients must be screened for active/latent TB. The issue of prophylaxis for TB is controversial and it has been suggested that all patients with positive Mantoux test, past history of TB or abnormal Chest X-Ray suggestive of TB should receive prophylactic anti-TB therapy. All the patients commenced on anti-TNF-α therapies need to be closely monitored for TB. This needs to be continued for 6 months after discontinuing infliximab treatment due to the prolonged elimination phase of infliximab. Patients on anti-TNF-α therapy who develop symptoms suggestive of TB should receive full anti-TB chemotherapy, and discontinue anti-TNF-α therapy. [53] The following observations have also been made regarding the use of anti-TNF-α therapy in RA: [53]

- There is no evidence to suggest that one type of anti-TNF-α therapy is more efficacious than the others.

- Infliximab can be useful when etanercept has failed and vice versa. There is also evidence for adalimumab substitution.

MTX has to be co-administered with infliximab. Although it is not necessary to co-prescribe MTX with etanercept, in patients with inadequate response to etanercept, the addition of MTX is a useful option and vice versa.

- Treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may be withheld for 2-4 weeks prior to major surgery and restarted post operatively.

- If live vaccines are required, they should ideally be given 4 weeks prior to commencing treatment or 6 months after the last infusion of infliximab (or potentially earlier if risks from not vaccinating are high) or 2-3 weeks after the last dose of etanercept.

Special precautions have to be taken while using the DMARDs and biologic therapy in the presence of renal failure, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, history of demyelinating disease, pregnancy and lactation.

Surgery

Synovectomy may be considered in a patient with refractory arthritis involving a single joint. Joint replacement can be considered in patients with severe involvement of hip or knee joints.

Conclusion

In conclusion, broad management of PsA is similar to RA. SSZ should be preferred in patients with mild disease. MTX should be the drug of choice in patients with moderate to severe disease. Cyclosporine should be used in refractory disease. TNF blockers should also be considered in patients with refractory disease.

Finally, patient education, early diagnosis, institution of early appropriate therapy, physiotherapy and rehabilitation therapy backed by surgical intervention for permanently damaged joints are the cornerstones for satisfactory treatment outcomes.

| 1. |

Alibert JL. Precis Theoretique sur les maladies de la peau. Paris: Caille et Ravier ; 1818. p. 21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Blumberg BS, Bunim JJ, Calkins E, Pirani CL, Zvaifler NJ. Nomenclature and classification of arthritis and rheumatism (tentative) accepted by the American Rheumatism Association. Bull Rheum Dis 1964;14:339-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Gladmann DD. Psoriatic arthritis. In: Gordon K, Ruderman E, editors. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2005. p. 57-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Bedi TR. Clinical profile of psoriasis in North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1995;61:202-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Moll JM, Wright V. Familial occurrence of PsA. Ann Rheum Dis 1973;32:181-201.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Malviya AN, Dasgupta B, Tiwari SC, Khan KM, Pasricha JS, Mehra NK. Psoriatic arthritis: A clinical and immunological study in 15 cases from India. J Assoc Physicians India 1984;32:403-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Rajendran CP, Ledge SG, Rani KP, Madhavan R. Psoriatic arthritis. J Assoc Physicians India 2003;51:1065-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Bennett RM. Psoriatic arthritis. In: McCarty DJ, editors. Arthritis and related conditions, 9 th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1979. p. 645.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Vasey F, Espinoza LR. Psoriatic arthritis. In: Calin A, editors. Spondyloarthropathies. Orlando, Fla: Grune and Stratton; 1984. p. 151-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Gladman DD, Shuckett R, Russell ML, Thorne JC, Schachter RK. Psoriatic arthritis- an analysis of 220 patients. Q J Med 1987;238:127-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

McGonagle D, Conaghan PG, Emery P. Psoriatic arthritis. A unified concept twenty years on. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1080-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Fournie B, Crognier L, Arnaud C, Zabraniecki L, Lascaux-Lefebvre V, Marc V, et al. Proposed classification criteria of Psoriatic arthritis. A preliminary study in 260 patients. Rev Rhum Eng Ed 1999;66:446-56.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Rahman P, Nguyen E, Cheung C, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Comparison of radiological severity in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1021-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Girolomini G, Gisondi P. Psoriasis and systemic inflammation; underdiagnosed enthesopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 2009;23:3-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Husted JA, Gladmann DD, Farewell VT, Cook RJ. Health related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: A comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis care Res 2001;45:151-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Mease PJ. Recent advances in the management of psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:366-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, Bijlsma JW. Tight control in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: Efficacy and feasibility. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:56-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: Epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:14-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Qureshi AA, Dominguez P, Duffin KC, Gladman DD, Helliwell P, Mease PJ, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening tools. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1423-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Griffith CEM. Therapy for psoriatic arthritis: Sometimes a conflict for psoriasis. Br J Rheumatol 1997;36:409-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Nash P. Management of Psoriatic arthritis. In: Psoriatic and reactive arthritis. Ritchlin CT, FitzGerald O, editors. 1 st ed. Philadelphia: Publishers Mosby; p. 97-113. 2007

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Kirwan JR. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. The Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low-Dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. New Eng J Med 1995;333:142-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Abdellatif M. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondylarthropathies: A Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:2325-39.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Black RL, O′Brien WM, Van Scott EJ, Auerbach R, Eisen AZ, BunimJJ. Methotrexate therapy in psoriatic arthritis. JAMA 1964;189:141.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Kragballe K, Zachariae E, Zachariae H. Methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis: A retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol 1983;63:165-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Espinoza LR, Zakraoui L, Espinoza CG, Gutiιrrez F, Jara LJ, Silveira LH, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: Clinical response and side effects to methotrexate therapy. J Rheumatol 1992;19:872-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Jones G, Crotty M, Brooks P. Interventions for treating psoriatic arthritis http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab000212.html.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 4. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:451-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Kalb RE, Strober B, Weinstein G, Lebwohl M. Methotrexate and psoriasis: 2009 National Psoriasis Foundation consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:824-37.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Lindsay K, Fraser AD, Layton A, Goodfield M, Gruss H, Gough A. Liver fibrosis in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis on long-term, high cumulative dose methotrexate therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:569-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Singh YN, Verma KK, Kumar A, Malaviya AN. Methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis. J Assoc Physicians India 1994;42:860-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Chandran V, Gottlieb A, Cook RJ, Duffin KC, Garg A, Helliwell P, et al. International multicenter psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis reliability trial for the assessment of skin, joints, nails, and dactylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1235-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Marcil I, Stern RS. Squamous-cell cancer of the skin in patients given PUVA and cyclosporin: Nested cohort crossover study. Lancet 2001;358:1042-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Nash P, Clegg DO. Psoriatic arthritis therapy: NSAIDs and traditional DMARDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:74-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Alivernini S, Mazzotta D, Zoli A, Ferraccioli G. Leflunomide treatment in elderly patients with rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis: Retrospective analysis of safety and adherence to treatment. Drugs Aging 2009;26:395-402.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Leflunomide: A review of its use in active rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 1999;58:1137-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Perlman SG, Gerber LH, Roberts RM, Nigra TP, Barth WF. Photochemotherapy and psoriatic arthritis. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1979;91:717-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Schrader P, Mooser G, Peter RU, Puhl W. Preliminary results in therapy of psoriatic arthritis with mycophenolate mofetil [in German]. Z Rheumatol 2002;61:545-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Lee JCT, Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Cook RJ. The long-term use of azathioprine in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2001;7:160-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Gladman DD, Blake R, Brubacher B, Farewell VT. Chloroquine therapy in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 1992;19:1724-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Carrette S, Calin A. Evaluation of auranofin in psoriatic arthritis: A double blind placebo controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:158-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Palit J, Hill J, Capell HA, Carey J, Daunt SO, Cawley MI, et al. A multicentre double-blind comparison of auranofin, intramuscular gold thiomalate and placebo in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1990;29:280-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Siegel EL, Cohen SB, Ory P, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2264-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Sterry W, Ortonne JP, Kirkham B, Brocq O, Robertson D, Pedersen RD, et al. Results of a radomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of etanercept in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: the PRESTA trial. Psoriasis Gene to Clinic, London; 2008.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1150-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

van der Heijde D, Kavanaugh A, Beutler A, Antoni C, Krueger GG, Guzzo C, et al. Infliximab inhibits progression of radiographic damage in patients with active psoriatic arthritis through one year of treatment: Results from the induction and maintenance psoriatic arthritis clinical trial 2. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2698-707.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Kraan MC, van Kuijk AW, Dinant HJ, Goedkoop AY, Smeets TJ, de Rie MA, et al. Alefacept treatment in psoriatic arthritis: Reduction of the effector T cell population in peripheral blood and synovial tissue is associated with improvement of clinical signs of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2776-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Mease PJ, Reich KD. Alefacept with methotrexate for treatment of psoriatic arthritis: open-label extension of a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;60:402-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Gottlieb A, Menter A, Mendelsohn A, Shen YK, Li S, Guzzo C et al. Ustekinumab, a human interleukin 12/23 monoclonal antibody, for psoriatic arthritis: Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, crossover trial. Lancet 2009;373:633-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Jung N, Hellmann M, Hoheisel R, Lehmann C, Haase I, Perniok A et al. An open-label pilot study of the efficacy and safety of anakinra in patients with psoriatic arthritis refractory to or intolerant of methotrexate (MTX). Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Jun 9. [Epub ahead of print]

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, Ramos-Remus C, Rovensky J, Alecock E et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:987-97.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Misra R, Sharma BL, Gupta R, Pandya S, Agarwal S, Agarwal P, et al. Indian Rheumatology Association consensus statement on the management of adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Indian J Rheumatol 2008;39:S1-S6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Misra R, Amin S, Joshi VR, Rao URK, Aggarwal A, Fatima F, et al. Open label evaluation of the efficacy and safety of etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis. J Indian Rheumatol Assoc 2005;13:131-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Grover R, Kapoor S, Marwaha V, Malaviya AN, Gupta R, Kumar A. Clinical experience with infliximab in spondyloarthropathy: an open label study of 14 patients. J Indian Rheumatol Assoc 2005;13:78-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,156

PDF downloads

2,723