Translate this page into:

Mindful self-compassion for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: An online intervention study

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sengupta A, Wagani R. Mindful self-compassion for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: An online intervention study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol doi 10.25259/IJDVL_451_2023

Abstract

Background

Chronic skin conditions are different from internal illnesses since they are often immediately visible to others. Patients feel self-conscious and often go through depression, anxiety, fear of stigma and a substantial psychological, social and economic impact. It is crucial for healthcare professionals to gather information about various strategies and psychosocial interventions that can be used to manage psychological distress associated with skin conditions and avoid it from being neglected amidst other health conditions. Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) can be used for this. It is a resource-building mindfulness-based self-compassion training programme that uses a combination of personal development training and psychotherapy designed to enhance one’s capacity for self-compassion by cultivating spacious awareness as a basis for compassionate action.

Aims

This study examined the impact of mindful self-compassion on depression, anxiety, stress, dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being in a sample of 88 adults aged 18–55 years suffering from chronic skin conditions.

Methods

This study used an experimental waitlist control design. Participants were recruited from two skin clinics using purposive sampling in Mumbai, Maharashtra. Pre-test data was collected through self-reported questionnaires on psychological distress, dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being. Participants who were experiencing psychological distress were randomly assigned to either the experimental or waitlist control group. The intervention named ‘mindful self-compassion’ was delivered through an online platform, twice a week, over a period of 4 weeks. Post-test data was collected later on all variables.

Results

ANCOVA was utilised where pre-test scores were used as covariates. Differences in pre-test and post-test scores between the intervention group and waitlist control group for depression, anxiety, stress, dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being were analysed. Participants in the intervention group were found to have lower levels of depression, anxiety and stress as compared to the waitlist control group and also had enhanced levels of self-esteem, well-being and dermatological quality of life. These differences were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Limitations

The sample reflected heterogenous skin conditions, not a specific skin condition. The study was quantitative in nature, and we could not use any qualitative methods to assess the subjective experience of participants. Due to time constraints, follow-up data could not be gathered from participants to assess long-term effects on participants.

Conclusion

Mindful self-compassion can be effectively used to manage psychological distress in skin conditions. Dermatologists can become acquainted with basic signs of mental distress and the importance of psychological interventions. By collaborating with mental health professionals, patients can be given holistic treatment.

Keywords

Psycho-dermatology

anxiety

depression

dermatology life quality index

mindful self-compassion

Plain Language Summary

Many individuals suffer from skin conditions for several years, even a lifetime. Such conditions are often immediately visible to others and patients feel self-conscious. Many go through mental distress such as depression, anxiety and poor self-esteem which need to be managed. This study administered mindful self-compassion training in adults with skin conditions who reported high levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Participants were requested to fill questionnaires before and after the intervention was provided. The group of participants who received the intervention for 4 weeks were compared to another group of participants who did not receive the intervention, and the pre-test and post-test scores were compared. Results indicated that the group of participants who received the intervention had reduced levels of depression, anxiety and stress as compared to the control group who did not receive the intervention. They also had improved levels of self-esteem, well-being and quality of life. Such an intervention can be effectively used to manage psychological distress in individuals with skin conditions. Mental health professionals and dermatologists together can provide patients with holistic treatment. In view of ethical equality, the control group was also provided with mindful self-compassion training after the end of the study.

Introduction

Recent research on the burden of chronic skin diseases and associated distress has shown psychological, social and financial costs on patients and families.1 Patients with chronic skin conditions often go through multiple hurdles, which impairs their psychosocial functioning.2 Many studies worldwide indicate associated mental distress in skin conditions. Research has found association of dermatological conditions with clinical depression,3-8 clinical anxiety,5,6 suicidal ideation,3,4,9 low self-esteem10–12 and poor quality of life.6,10,12 Skin diseases are different from internal illnesses since they are often immediately noticeable to others. One’s appearance may differ from the normal. The visibility of such conditions make them ‘life-ruining’, and persons with disfigurement often feel devastated.13 Individuals face stigma due to this apparent nature of skin conditions and develop a constant fear of stigma, which impacts their lives negatively.2,8 Many go through problems of teasing, taunting and bullying.14 They experience poor social functioning,6,7,9 decreased interactions,9,11 loneliness7 and social phobia.13

The benefits of mindfulness interventions for mental and physical health outcomes have been established by research.15 Meta-analytic and systematic review studies indicate that mindfulness-based interventions show improvement in depression,16,17 anxiety17,18 and stress.17,19 Such interventions decrease emotional distress in psoriasis,20,21 acne21 and eczema.21,22 Self-compassion interventions have shown significant improvement in rumination, stress, depression, self-criticism and anxiety.23 Patients with chronic skin conditions go through a lifelong struggle. However, the psychosocial part of management remains overlooked.7 Mindful self-compassion can cover this treatment gap. It is a resource-building mindfulness-based self-compassion training programme that uses a combination of personal development, training and psychotherapy designed to enhance one’s capacity for self-compassion by cultivating spacious awareness as a basis for compassionate action.24,25

Hence, we conducted a study to assess the impact of this intervention on depression, anxiety, stress, dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being in adults suffering from chronic skin conditions.

Methods

The research was conducted after approval by the ethical committee of Amity Institute of Behavioural and Allied Sciences, Amity University, Mumbai (Letter No. AUM/AIBAS/EC/2022/01). Purposive sampling technique was used. Participants were recruited from two private dermatology skin clinics in Mumbai, after debriefing dermatologists and taking permissions. The two clinics were Sparsh clinic and Gosavi’s skin clinic. These patients were visiting dermatologists for their skin concerns and were receiving concurrent pharmacological care. Initially 422 participants aged 18–55 years with heterogeneous skin conditions completed forms giving their socio-demographic details, clinical characteristics, as well as self-reported Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 questionnaire (DASS-21), which assesses levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Informed and written consent was taken beforehand.

The inclusion criteria were voluntary participation, having a symptomatic skin condition for a minimum of 6 months, receiving a formal diagnosis from a dermatologist, proficiency in English for completing self-report questionnaires and to engage in the intervention,psychological distress (experiencing higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress based on the scale and scores above cut-off). Exclusion criteria included those receiving any concurrent treatment for a mental illness, those already practising specific mindfulness meditation techniques, those reporting current thoughts or acts of self-harm or suicide and pregnancy. Shortlisted participants were contacted and debriefed about their scores and psychological distress. They were educated about mental health services and treatment options. Those interested in participating in the study were requested to fill the Dermatology Quality of Life Scale, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and World Health Organization Well-Being Index to obtain pretest scores.

A waiting-list control design was used where participants were randomised to the intervention condition or waitlist control group. Messages and emails were sent to the participants with details of the study, dates, timing and Google meet link with reminders. In the first and last sessions, they were told about the concept of mental health and illness, their high distress scores and the need to seek services from psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. The intervention was used in a group format over a period of 4 weeks with online sessions taking place twice a week. Participants could attend either a morning or an evening session based on their convenience. The intervention was conducted by two trained clinical psychologists. Each session lasted 50 minutes. Different guided mindfulness and self-compassion techniques (for example, exercises like providing a soothing touch to self and writing a compassionate letter towards the self) were practised in every session to induce grounding and relaxation and their rationale was explained. The facilitators also elicited discussions to change the approach of participants and develop an approach towards the self with kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, acceptance and gratitude. Participants who completed all eight sessions were requested to fill the questionnaires again as a post-test outcome measure. To maintain ethical guidelines, the waitlist control was provided with the same intervention after data collection.

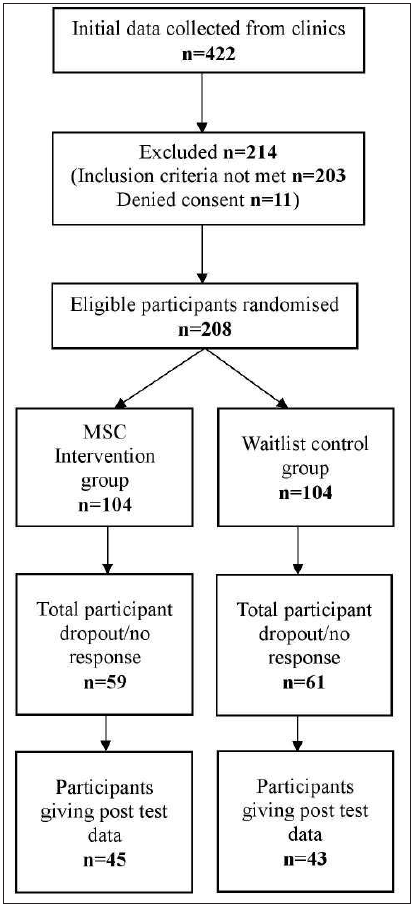

The final sample consisted of 88 participants [Figure 1]. All data analyses were performed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 27.

- A CONSORT chart of the study (MSC: Mindful Self-Compassion).

Results

The demographic distribution and clinical features of the participants has been showcased in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Acne was the most common disorder, in 29 (32.9%) participants. Thirty-one participants were in the age group of 36–45 years (35.2%). The study comprised 59 females (67%) and 29 males (33%).

Table 3 indicates the mean pre-test and post-test scores for each domain. At the end of the study, the mean scores for depression, anxiety, stress and dermatology life quality index on post-test evaluation were found to be lower for the intervention group as compared to the waitlist control group. The mean scores for well-being and self-esteem on post-test evaluation were found to be higher for the intervention group as compared to the waitlist control group.

ANCOVA was used to test for differences in levels of depression, anxiety, stress, dermatology life quality index, self-esteem and well-being between the intervention and waitlist-control groups. For each domain, the pre-test scores were used as a covariate to assess for post-test differences between the intervention group and waitlist control group. The difference in means of depression, anxiety, stress, dermatology life quality index, self-esteem and well-being between the intervention group and waitlist control group was found to be statistically significant using the ANCOVA model (p < 0.001) [Table 4]. At the end of the study, the intervention group had reduced psychological distress and enhanced dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being as compared to the waitlist control.

| Domain | MSC intervention group (n = 45) | Waitlist control group (n = 43) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 18–25 | 13 (28.9%) | 11 (25.6%) | 24 (27.3%) |

| 26–35 | 14 (31.1%) | 11 (25.6%) | 25 (28.4%) | |

| 36–45 | 17 (37.8%) | 14 (32.6%) | 31(35.2%) | |

| 46–55 | 1 (2.2%) | 7 (16.3%) | 8 (9.1%) | |

| Sex | Male | 14 (31.1%) | 15 (34.9%) | 29 (33%) |

| Female | 31 (68.9%) | 28 (65.1%) | 59 (67%) | |

| Highest educational qualification | Senior secondary | 8 (17.8%) | 10 (23.3%) | 18 (20.5%) |

| Graduate | 24 (53.3%) | 24 (55.8%) | 48 (54.5%) | |

| Postgraduate | 13 (28.9%) | 8 (18.6%) | 21 (23.9%) | |

| Super speciality | 0 | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Religion | Hindu | 26 (57.8%) | 31 (72.1%) | 57 (64.8%) |

| Muslim | 10 (22.2%) | 6 (14%) | 16 (18.2%) | |

| Jain | 4 (8.9%) | 1 (2.3%) | 5 (5.7%) | |

| Sikh | 2 (4.4%) | 3 (7%) | 5 (5.7%) | |

| Christian | 3 (6.7%) | 2 (4.7%) | 5 (5.7%) | |

| Socio-economic Status | Upper | 14 (31.1%) | 12 (27.9%) | 26 (29.5%) |

| Middle | 31 (68.9%) | 31 (72.1%) | 62 (70.5%) | |

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 29 (64.4%) | 24 (55.8%) | 53 (60.2%) |

| Unmarried | 16 (35.6%) | 19 (44.2%) | 35 (39.8%) | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 25 (55.6%) | 19 (44.2%) | 44 (50%) |

| Unemployed | 20 (44.4%) | 24 (55.8%) | 44 (50%) |

MSC: Mindful self-compassion

| Skin condition | MSC intervention group (n = 45) | Waitlist control group (n = 43) | Total (n = 88) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne | 15 (33.3%) | 14 (32.5%) | 29 (32.9%) |

| Atopic Dermatitis | 11 (24.4%) | 10 (23.2%) | 21 (23.8%) |

| Psoriasis | 6 (13.3%) | 6 (13.9%) | 12 (13.6%) |

| Vitiligo | 4 (8.8%) | 4 (9.3%) | 8 (9%) |

| Rosacea | 3 (6.6%) | 3 (6.9%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Other | 5 (1.1%) | 2 (4.6%) | 7 (1.1%) |

| 2 or more | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (6.9%) | 4 (4.5%) |

MSC: Mindful Self-Compassion

| MSC intervention group | Waitlist control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test (Mean ± SD) | Post-test (Mean ± SD) | Pre-test (Mean ± SD) | Post-test (Mean ± SD) | |

| Depression | 14.95 ± 2.41 | 3.20 ± 1.70 | 15.27 ± 2.23 | 15.33 ± 2.03 |

| Anxiety | 12.66 ± 2.70 | 2.76 ± 1.88 | 13.58 ± 2.24 | 13.81 ± 2.11 |

| Stress | 16.31 ± 1.26 | 4.89 ± 1.78 | 16.79 ± 1.37 | 16.44 ± 1.46 |

| Dermatology Quality of Life | 23.86 ± 4.67 | 10.02 ± 3.68 | 24.76 ± 3.58 | 24.84 ± 4.04 |

| Self-esteem | 15.84 ± 1.53 | 24.56 ± 0.72 | 26.11 ± 1.64 | 26.07 ± 1.59 |

| Well-being | 11.86 ± 2.46 | 22.20 ± 1.63 | 8.32 ± 2.16 | 8.33 ± 1.83 |

MSC: Mindful Self-Compassion

S.D: Standard deviation

| Measurement | F | Significance | Partial ETA squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1789.554 | P < 0.001 | 0.995 |

| Anxiety | 1105.770 | P < 0.001 | 0.929 |

| Stress | 1561.326 | P < 0.001 | 0.948 |

| Dermatology quality of life | 712.097 | P < 0.001 | 0.893 |

| Self-esteem | 43.324 | P < 0.001 | 0.338 |

| Well-being | 1160.759 | P < 0.001 | 0.932 |

ANCOVA: Analysis of Covariance

Discussion

The results indicate that mindful self-compassion (MSC) was effective and showed significant reduction in psychological distress in individuals with chronic skin conditions. This is consistent with previous studies where mindfulness and self-compassion based interventions have shown reduction in depression,20,26,27 anxiety20,26,27 and stress,20,22,27 and boosted levels of dermatology-specific quality of life,20,27,28 self-esteem21 and well-being.26,28

Mindfulness fosters awareness of the present moment, which enhances the vividness of life. Individuals with skin conditions face stigma,2,8 fear of stigma,2,8 humiliation,13 teasing,14 taunting,14 bullying,14 social phobia,13 poor socialisation.6,7,9,11 Their attention remains in their disfigurement and they neglect other experiences, self-criticise, ruminate about the past, or worry about the future.15 The awareness, relaxation and acceptance as a result of mindfulness reduced the experiential avoidance, self-judgment and rumination which is associated with depression, anxiety and low self-esteem.15,29 It enhances emotional regulation and helps cope with challenges.29 This protects one from the impact of stress associated with skin diseases and affects stress-related disease outcomes like dermatology-specific quality of life, self-esteem and well-being.29 Self-compassion helped participants become gentle, forgiving, supportive and sympathetic towards themselves. Participants realised that perfection is unrealistic, all humans are flawed and that negative experiences are universal. Disfigurement, bullying, teasing, rejection, criticism, loneliness, stigma are faced by many.24,25

This study indicates how a mindfulness and self-compassion-based intervention is effective for psychological distress associated with skin conditions. It also highlights the need for psycho-dermatology liaison services. Dermatologists should be wary of emotional disturbance in patients and can give referrals to mental health professionals when required. This intervention can be used effectively by mental health professionals and treatment protocols can be created for psycho-dermatology settings.

Limitations

The current study has certain limitations and scope for future research. The sample consisted of heterogeneous skin conditions. Further mindful self-compassion intervention studies can be done to understand the impact on specific skin conditions. Due to time constraints, we could not employ qualitative methods to assess subjective experiences of participants or gather follow up data to assess long-term effects. We also could not assess reasons for participant dropouts. Lastly, the sample consisted of participants from middle and upper socio-economic class only.

Conclusion

Mindful self-compassion can be used to manage psychological distress in skin conditions. Dermatologists can become acquainted with basic signs of mental distress and the importance of psychological interventions. By collaborating with mental health professionals, patients can be given holistic treatment.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the departmental ethics review committee, Amity University Maharashtra (AUM/AIBAS/EC/2022/01). Informed and written consent was obtained from all participants, and their privacy and confidentiality were maintained.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Burden of skin diseases. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:271-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumulative life course impairment in other chronic or recurrent dermatologic diseases. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2013;44:130-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of depression and suicidal risk in patients with psoriasis: A hospital-based cross sectional study. J Med Soc. 2022;36:124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and suicidal ideation in patients with acne, psoriasis, and alopecia areata. J Ment Health Human Beh. 2017;22:50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. J Dermatol. 2001;28:424-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study of prevalence and implications of depression and anxiety in psoriasis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:434-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial impact of skin diseases: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0244765.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The psychosocial and occupational impact of chronic skin disease. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:54-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among patients with skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:420-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Body image, self-esteem, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:343-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Burden of disease: The psychosocial impact of rosacea on a patient’s quality of life. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:348-54.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Acne vulgaris on quality of life and self-esteem. Cutis. 2016;98:121-4.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psycho dermatology: The mind and skin connection. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1873-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of appearance-related teasing and bullying in skin diseases and their psychological sequelae: Results of a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22:430-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of mindfulness meditation interventions on depression in older adults: A meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1181-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on nursing students: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;98:104718.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of mindfulness meditation on college student anxiety: Analysis. Mindfulness. 2019;10:203-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Systematic review of mindfulness interventions on psychophysiological responses to acute stress. Mindfulness. 2020;11:2039-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pilot study examining mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in psoriasis. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20:121-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Acceptance and mindfulness-based intervention as an add-on treatment for skin diseases-Acne, eczema and psoriasis. SSR Institute of Int J Life Sci. 2020;6:2652-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pilot study of a mindfulness-based stress reduction programme in patients suffering from atopic dermatitis. Psych. 2021;3:663-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness. 2019;10:1455-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teaching the Mindful Self-Compassion Program: A Guide for Professionals. New York: The Guilford Press 2019:75-144.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with psoriasis patients. Mindfulness. 2019;10:2606-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compassion-focused self-help for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: A randomized feasibility trial. Psychol Health. 2020;35:1095-114.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindfulness-based interventions for psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2018;10:288-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23:401-7.

- [Google Scholar]