Translate this page into:

Morbihan disease: Look beyond facial lymphedema

2 Department of Pathology, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Correspondence Address:

Prince Yuvraj Singh

Department of Dermatology, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Singh PY, Baveja S, Vashisht D, Sharma M, Sengupta P. Morbihan disease: Look beyond facial lymphedema. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2020;86:418-421 |

Sir,

Morbihan disease is characterized by chronic and recurrent pattern of symmetrical facial edema and erythema, over the middle and upper thirds of the face (malar regions, nose, glabella, eyelids and forehead). Its pathogenesis remains largely unknown but the clinical manifestations are presumably caused by derangements in local cutaneous vasculature and imbalance between lymph production and drainage.[1] Some authors also hypothesize that a primary lymph vessel abnormality in the involved skin is the underlying cause. We report a case of this rare entity, in association with primary genital lymphedema.

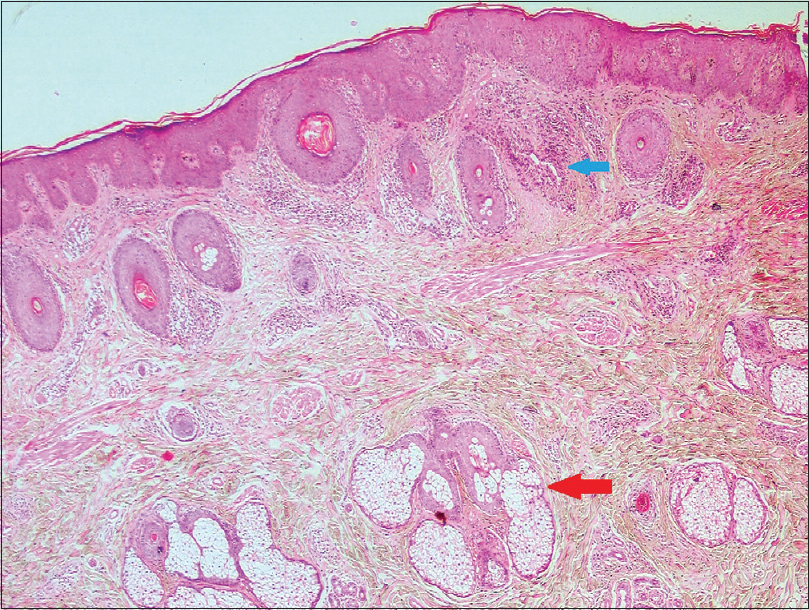

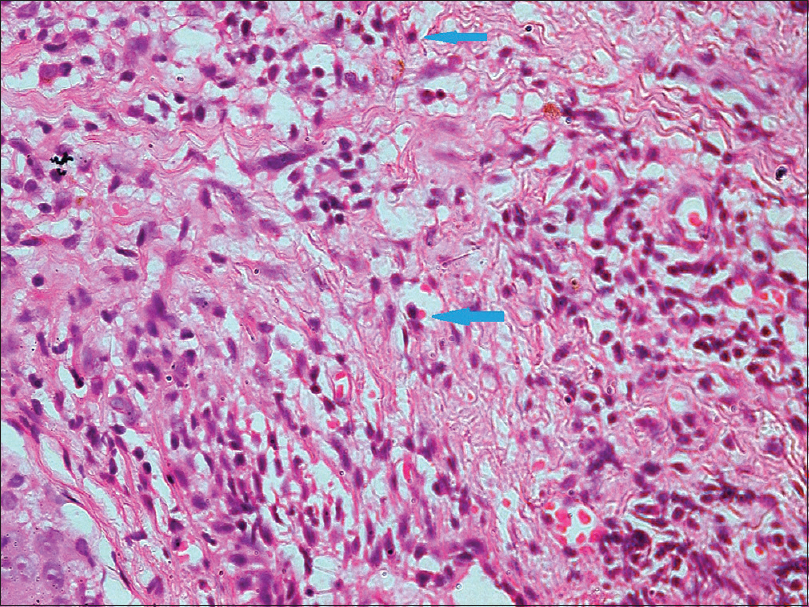

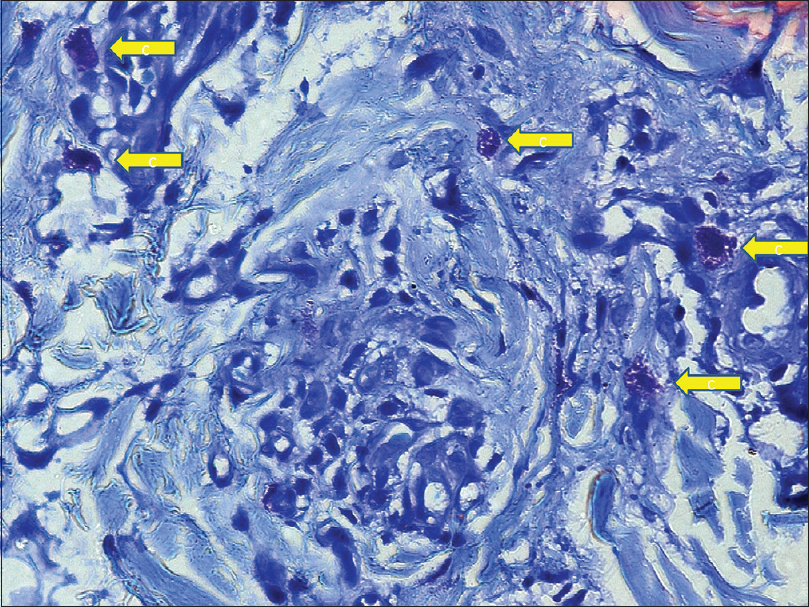

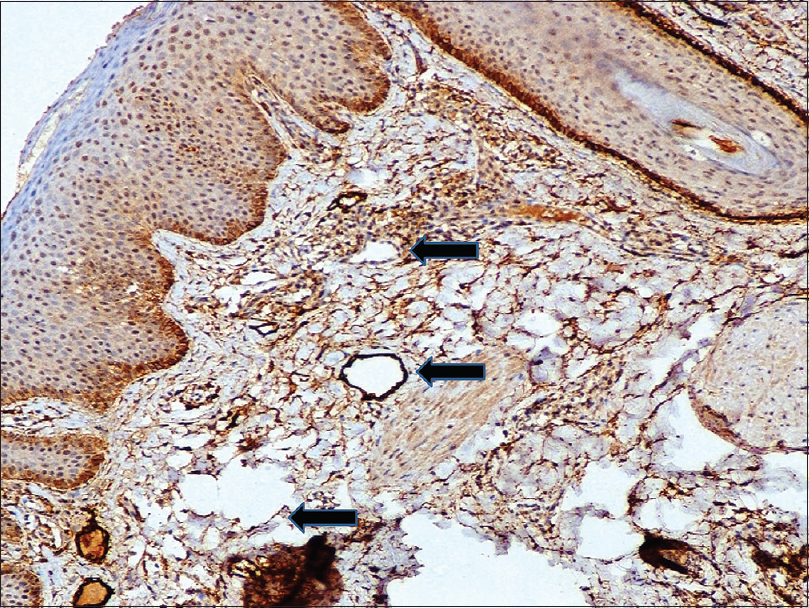

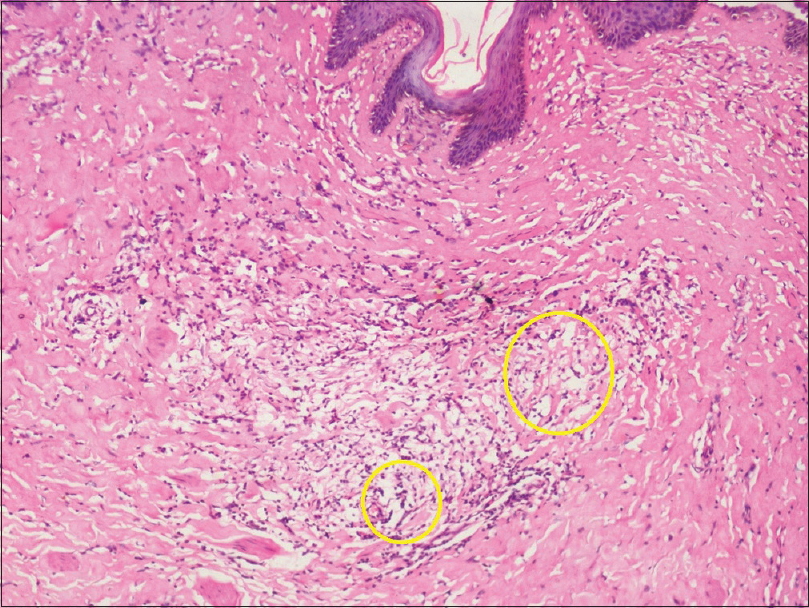

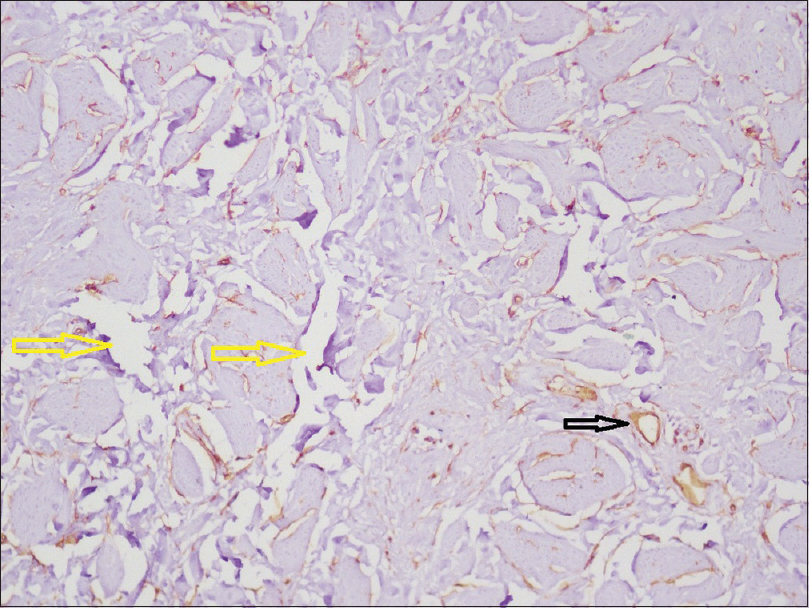

A 23-year-old male presented with complaints of swelling and redness of the upper eyelids and face, of 7 years duration. The swelling initially started on the upper eyelids and gradually progressed over the next few years to involve the forehead and both cheeks. He denied any pain, itching or worsening of symptoms after sun exposure. There was no history of association with food intake, stress, contact allergy or any visual symptoms. Two years prior to the onset of the facial rash, he was diagnosed with primary penoscrotal lymphedema when he developed progressive penoscrotal swelling causing urinary obstruction and difficulty in retraction of the prepuce. He underwent scrotoplasty and circumcision with relief from urinary symptoms; however, the penoscrotal edema persisted. Dermatological examination revealed erythematous edema with mild scaling involving the forehead, glabella, cheeks and both upper and lower eyelids, causing difficulty in opening his eyes completely [Figure - 1]. There was edema of the penis and scrotum with deformity of the penis [Figure - 2] and increased rugosity of the scrotal skin along with healed scars [Figure - 3]. Dermoscopic examination of the lesions on the face revealed linear vessels and white chrysalis-like structures on a yellow background. Differential diagnoses of Morbihan syndrome, Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome, sarcoidosis and granuloma faciale were considered. All laboratory investigations including hematologic, biochemical and serological investigations, serum angiotensin converting enzyme levels, chest X-ray and high-resolution computed tomography thorax were normal. Histopathological examination of a punch biopsy done from the forehead revealed sebaceous gland hyperplasia, dermal edema, extravasation of RBCs and perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate [Figure - 4] composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells [Figure - 5]. Toluidine blue stain showed an increase in the number of mast cells [Figure - 6]. Dilated lymphatic channels were seen in superficial and deeper dermis, lined by D2-40 positive endothelial cells [Figure - 7]. Histopathological examination of the scrotal skin revealed dermal edema, chronic inflammatory infiltrate and dilated ectatic lymphatics [Figure - 8]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) with CD-34 staining demonstrated normal arterioles lined by endothelial cells and dilated lymphatic channels [Figure - 9]. Taking into account all the findings, the patient was diagnosed as a case of Morbihan disease. Along with sun-protective measures and a broad-spectrum sunscreen application, he was started on cap isotretinoin 20 mg daily which was later increased to 40 mg daily and was continued for 24 weeks; however, no significant improvement was seen with the therapy.

|

| Figure 1: Erythematous solid edema with mild scaling, involving the face and both eyelids causing difficulty in opening the eyes completely |

|

| Figure 2: Edema of the penis and scrotum with deformity of the penis |

|

| Figure 3: Increased rugosity of scrotal skin along with healed scar marks |

|

| Figure 4: Sebaceous hyperplasia (red arrow) with a dense periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate (blue arrow) (H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 5: Inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 6: Numerous mast cells (yellow arrows) with prominent metachromatically stained cytoplasmic granules (toluidine blue, ×1000) |

|

| Figure 7: On immunohistochemistry, numerous dilated lymphatics (black arrows) lined discontinuous lining of D2-40 positive endothelial cells (IHC D2-40, ×400) |

|

| Figure 8: Scrotal biopsy: Dermal edema, chronic inflammatory infiltrate and dilated ectatic lymphatic vessels (yellow circles) (H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 9: Scrotal biopsy: Immunohistochemical staining showing normal arterioles lined by endothelial cells (black arrow) and numerous dilated lymphatic channels (yellow arrows) (immunohistochemistry CD34, ×400) |

Morbihan disease was first described by the French dermatologist Robert Degos in 1957. This condition was first reported from the French region of Morbihan (north-western France); hence, the name, Morbihan disease. Since its description, it has been called by several other names, including solid persistent facial edema, rosaceous lymphedema and morbus Morbihan. Clinically, it presents with chronic and recurrent symmetrical persistent erythema and solid edema of the upper two-thirds of the face.[1] Morbihan disease is predominantly seen in Caucasians and on a literature search; we could find only one Indian patient being reported previously with the disease.[2]

This disease is a likely manifestation of downstream effects from rosacea's recurrent episodes of vasodilation and chronic inflammation. Some authors also hypothesize that it may be caused by an underlying primary lymph vessel abnormality. Ultrasonography and laser Doppler flowmetry demonstrated a preexisting lymphatic drainage defect in the affected skin of one such patient with this condition.[3] Recently, immunohistochemical studies have shown an increase in D2-40 expression in the lymphatic endothelium of the skin affected by Morbihan disease, suggesting that a primary abnormality in lymphangiogenesis may be involved in the pathogenesis.[1]

Histopathological features of Morbihan disease include dermal edema, dilated blood vessels, perifollicular fibrosis and perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates. Rarely, increased mast cell infiltration may be seen and their degranulation may be the underlying cause of collagen deposition and fibrotic reaction seen in Morbihan disease.[4] Sebaceous gland hyperplasia may be observed and rarely, granulomas may also be present. In a case of Morbihan disease, dilated and damaged lymphatics with adjacent epithelioid cell granulomas and lymphatic obstruction were reported by Nagasaka et al.[5] Our patient had histopathological findings consistent with Morbihan disease, which were further reinforced by toluidine blue staining and immunohistochemical staining.

Along with the classical findings of Morbihan disease, our patient had primary genital lymphedema. Genital lymphedema occurs as a result of accumulation of lymph in the superficial lymph vessels between the skin and fascia (Colles fascia in the scrotum and Buck's fascia of the penis). Primary lymphedema occurs due to hypoplasia or aplasia of the lymphatics and is classified as per the age of onset as congenital lymphedema variant (10%–20%) and the praecox variant (80%).[6] Our patient belonged to the latter group with the onset of genital lymphedema around 14 years of age.

Treatment options for Morbihan disease reported in the literature include isotretinoin, systemic antibiotics (tetracyclines, metronidazole), antihistamines (ketotifen), systemic corticosteroids, clofazimine and thalidomide which generally overlap with the management of rosacea.[7] However, at best, these drugs are associated with a reduction of only facial erythema with little or no improvement in facial edema.[7],[8] Although about 15%–20% of patients may not respond to isotretinoin, it is considered the first-line of therapy.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of Morbihan disease in association with primary genital lymphedema. Further research and studies are required to successfully comment on a definite association between this disease and the underlying primary lymphatic vessel abnormality, as hypothesized previously by a few authors.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the legal guardian has given his consent for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The guardian understands that names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal patient identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to our patient for his support and cooperation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Morales-Burgos A, Alvarez Del Manzano G, Sánchez JL, Cruz CL. Persistent eyelid swelling in a patient with rosacea.PR Health Sci J 2009;28:80-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Mahajan PM. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris. Cutis 1998;61:215-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Romiti N. Morbus morbihan: Solid and persistent facial edema and erythema in Portuguese. An Bras Dermatol 2000;75:599-603.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Fujimoto N, Mitsuru M, Tanaka T. Successful treatment of morbihan disease with long-term minocycline and its association with mast cell infiltration. Acta Derm Venereol 2015;95:368-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Nagasaka T, Koyama T, Matsumura K, Chen KR. Persistent lymphoedema in Morbihan disease: Formation of perilymphatic epithelioid cell granulomas as a possible pathogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008;33:764-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Namir SA, Trattner A. Transient idiopathic primary penoscrotal edema. Indian J Dermatol 2013;58:408.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Veraldi S, Persico MC, Francia C. Morbihan syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J 2013;4:122-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Ranu H, Lee J, Hee TH. Therapeutic hotline: Successful treatment of Morbihan's disease with oral prednisolone and doxycycline. Dermatol Ther 2010;23:682-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

7,907

PDF downloads

3,503