Translate this page into:

Mycophenolate mofetil

Correspondence Address:

Amar Surjushe

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, Grant Medical College and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Mumbai - 400 008, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Surjushe A, Saple D G. Mycophenolate mofetil. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:180-184 |

|

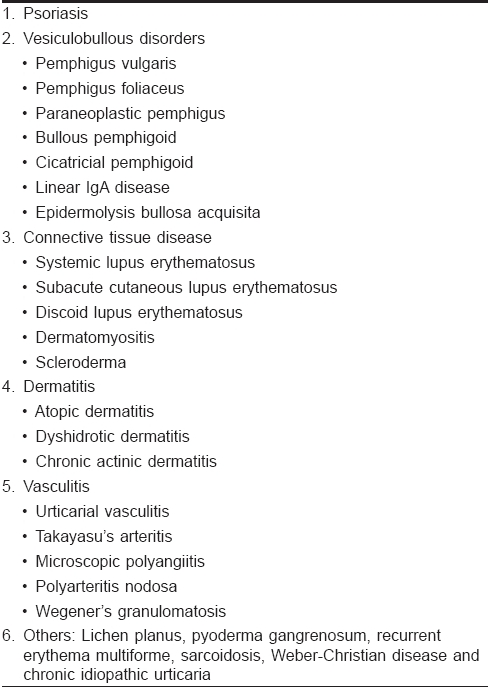

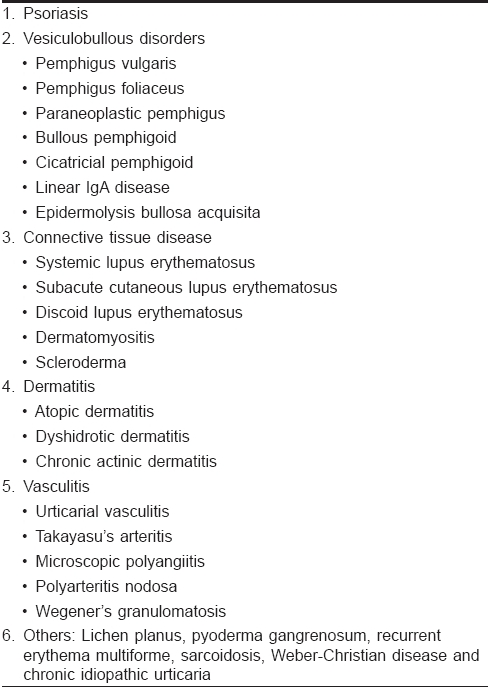

| Figure 1: Mechanism of action of mycophenolate mofetil |

|

| Figure 1: Mechanism of action of mycophenolate mofetil |

Introduction

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a novel immunosuppressant in the armamentarium of dermatologists, which is used for the treatment of immune-mediated skin disease. It is a prodrug of the active compound, mycophenolic acid (MPA). Originally isolated from cultures of Penicillium stoloniferum as a fermentation product, MPA was first recognized as a lipid-soluble, weak organic acid. [1] Currently approved for the prevention of organ rejection, its "off-label" indications in various dermatological disorders are increasing, although controlled trials are needed to know its real efficacy.

Mechanism of Action

Mycophenolate mofetil is a semisynthetic 2-morpholinoethyl ester. It is a prodrug, which is rapidly converted in vivo to the active metabolite, MPA by plasma esterase. MPA is a potent immunosuppressive agent and acts as a selective, uncompetitive and reversible inhibitor of the enzyme, inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), a key enzyme in the de novo purine biosynthesis pathway. IMPDH is an enzyme required for the conversion of inosine monophosphate (IMP) and xanthine monophosphate (XMP) to guanosine monophosphate, which is an important substrate for the synthesis of DNA and RNA [Figure - 1]. [2],[3]

There are two isoforms of IMPDH: Type I and type II. The IMPDH type I isoform is used by nonreplicating cells while the IMPDH type II isoform is predominantly used by proliferating lymphocytes. MPA has five times higher binding affinity for the IMPDH type II isoform and therefore, causes depletion of guanosine nucleotides, inhibition of DNA synthesis and the arrest of replicating lymphocytes in the S phase. [4] Thus, MMF is more cytotoxic to proliferating T and B-lymphocytes.

T and B lymphocytes depend upon de novo synthesis of purines for their proliferation, whereas other cell types can utilize the salvage pathway, i.e., hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase pathway for their proliferation. [5] MPA thus, has more potent cytostatic effects on T and B lymphocytes and causes decreases in the levels of immunoglobulins and delayed type hypersensitivity responses. [6] MMF also prevents the glycosylation of lymphocyte and monocyte glycoproteins that are involved in adhesion to endothelial cells. Thus, it inhibits chemotaxis, impairs antigen presentation and induces immune tolerance. [7]

Pharmacokinetics

MMF is well absorbed orally with a mean bioavailability of 94% and is predominantly bound to albumin. Food intake decreases the C max level due to which MMF should be taken on an empty stomach. In the liver, it is rapidly conjugated to form the pharmacologically inactive mycophenolic acid glucuronide (MPAG). [8],[9]

After absorptoin, MPA shows two peak levels in plasma. The first peak occurs approximately one hour after intake and the secondary peak is seen six to eight hours later. The first peak is due to the distribution of the drug and the second peak is due to enterohepatic recirculation of MPAG which is hydrolyzed back to MPA in the gastrointestinal tract by beta-glucuronidase. The elimination half-life of MPA is approximately 18 h and approximately 87% of the oral dose is excreted as MPAG in the urine and 6% is eliminated in feces. [9],[10]

Dosages

MMF is available as 250 mg capsules, 500 mg tablets and a powder for oral suspension (200 mg/ml). It is available as a lyophilized, sterile powder in a vial, which contains the equivalent of 500 mg MMF as the hydrochloride salt for intravenous administration.

In adults, the usual dose of MMF ranges from 1.25 to 2 g day. The dose can be tapered to 1 g daily in divided doses with improvement in skin conditions. In pediatric patients, it is administered as a 600-mg/m 2 dose every 12 h up to a maximum daily dose of 2 g. Dose reduction should be considered in patients with severe renal impairment. [11],[12]

Enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (ECMS) is available as delayed-release tablets containing either 180 or 360 mg of MPA. It can be used as an alternative in the patients with adverse MMF-induced gastrointestinal effects. [13]

Indications

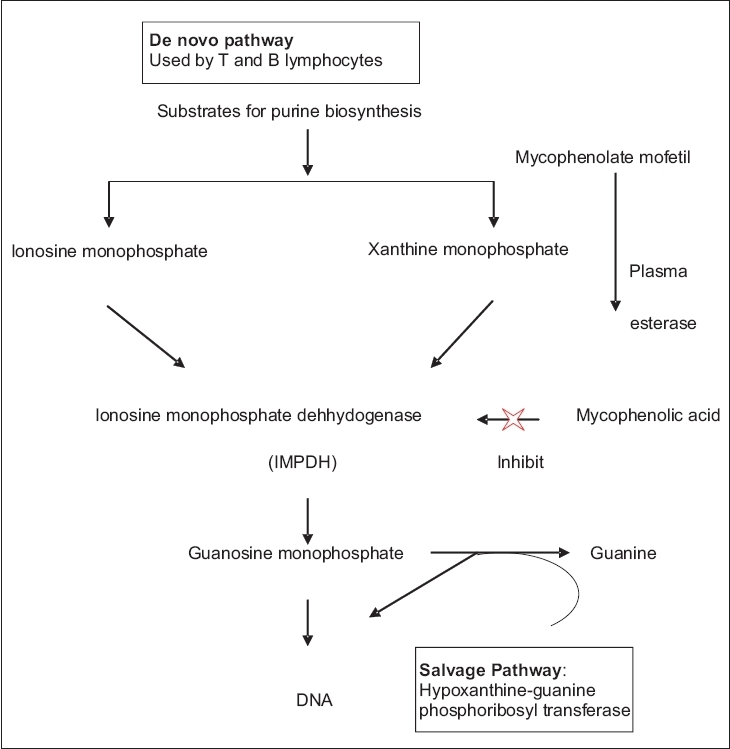

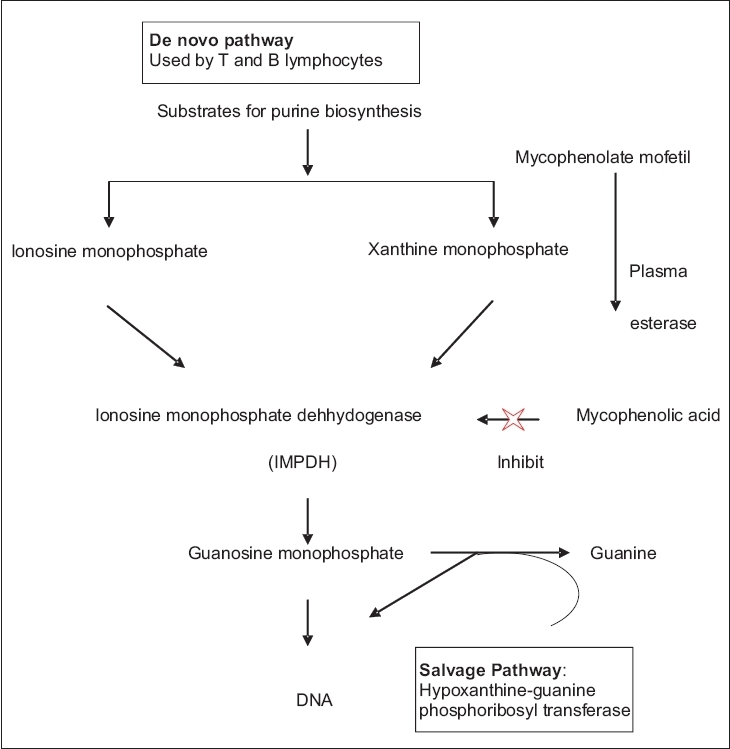

The only FDA-approved indication of MMF is for the prophylaxis of organ transplant rejection in conjunction with cyclosporine and corticosteroids. [14] It was first used in psoriasis in 1975 and since then, case reports and clinical trials document its use in various dermatological conditions as "off-label" indications [Table - 1]. MMF has been successfully used either as monotherapy or in combination with systemic steroids or as a steroid-sparing agent. MMF is best suited for individuals in whom other systemic immunotherapies are contraindicated because of hypertension, impaired renal function or liver disease. [15]

Although early reports have shown good efficacy and tolerability of MMF, randomized clinical trials with long surveillance periods are needed to document the efficacy and long-term safety of the drug in various skin diseases.

Psoriasis

In 1975-76, early open and placebo-controlled studies reported that MPA was effective in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, including those with severe refractory disease or intolerance to conventional therapy. [16] Recent studies also showed the benefit of MMF in psoriasis. MMF was reported to be effective in widespread plaque psoriasis, [17] moderate-to-severe psoriasis, [18] erythrodermic psoriasis, [19] refractory psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis at the dose of 2 g daily in these studies. [20]

Vesiculobullous disorders

MMF is mainly used as a steroid-sparing agent in blistering disorders. Mimouni et al. demonstrated complete remission of pemphigus in 22 out of 31 patients of pemphigus vulgaris (71%) and 5 out of 11 patients of pemphigus foliaceus (45%), who were recalcitrant to standard therapies with an average duration of 22 months. [21] Other studies have also demonstrated the effective use of MMF in other blistering disorders such as bullous pemphigoid, [22] paraneoplastic pemphigus, [23] cicatricial pemphigoid, [24] linear IgA disease [25] and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. [26]

Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, chronic actinic dermatitis and dyshidrotic eczema have been treated successfully with MMF. [27],[28]

Connective tissue diseases

Multiple studies have proved the efficacy of MMF in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It has been used effectively in diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis, [29] SLE-associated immune thrombocytopenia, [30] SLE with neuropsychiatric symptoms [31] and also in the prevention of clinical relapse of SLE. [32] Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus not responding to steroids, immunosuppressants or antimalarials and resistant cases of discoid lupus erythematous of palms and soles were treated successfully with MMF. [33],[34]

In dermatomyositis, MMF alone or in combination with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) can not only induce long-lasting remission but can also avoid adverse effects of long-term steroids. [35] In patients with diffuse scleroderma with recent, clinically apparent alveolitis, early treatment with MMF and corticosteroids may represent an effective, well-tolerated and safe alternative therapy. [36]

Vasculitis

MMF has been used in both small and large vessel vasculitis (Takayasu′s arteritis). [37],[38] It has been used with success for induction and maintenance therapy either alone or in combination with oral steroids.

Other skin diseases

Various studies and case reports have documented MMF to be effective in a variety of skin disorders like lichen planus (hypertrophic, bullous, ulcerative variety and lichen planopilaris), [39],[40] pyoderma gangrenosum, [41] Weber-Christian disease, [42] recurrent erythema multiforme, [43] sarcoidosis [44] and chronic idiopathic urticaria. [45]

Adverse Effects

The most common dose-related side effects are gastrointestinal and genitourinary. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, constipation, vomiting and anorexia while genitourinary symptoms include urgency, frequency, dysuria, hematuria and sterile pyuria. [11] GI symptoms are usually managed either by dose reduction or by splitting the total dose into three or four doses per day.

Being an immunosuppressant, MMF increases the risk of bacterial, fungal and viral infections and has a long-term risk of carcinogenicity like lymphomas and skin malignancies. [2],[9]

Other reported adverse events include hematological (i.e., anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia), neurologic (i.e., headache, tinnitus, insomnia), cutaneous (i.e., exanthematous eruptions, onycholysis), cardiorespiratory (i.e., dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations) and metabolic (i.e., hypercholesterolemia, hyperglycemia, hypophosphatemia and hypo/hyperkalemia). [2],[9]

Contraindications

MMF is absolutely contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to any component of the drug and is included in pregnancy category C. [11],[15] Peptic ulcer disease, renal disease, hepatic disease, lactation and cardiopulmonary disease are the relative contraindications. [9]

Drug Interactions

Drugs such as acyclovir, ganciclovir and probenecid inhibit the tubular secretion of MMF and hence, increase its level while drugs like antacids (containing aluminum and magnesium), ferrous sulphate, metronidazole and fluoroquinolones decrease the absorption and bioavailability of MMF and decrease its blood level. Cholestyramine inhibits enterohepatic recirculation of MMF and decreases its level. Salicylates and furosemide compete with MMF for plasma albumin binding and hence, increase the elimination of MMF. Mycophenolic mofetil does not seem to interact with other immunosuppressive agents except azathioprine. A combination of MMF and azathioprine should not be used as both block purine synthesis by the same pathway. [2],[9],[11],[15]

Monitoring

Complete physical examination should be carried out at each visit or at least every 6-12 months to look for any opportunistic infections and malignancies. Complete blood counts should be performed at baseline and biweekly during the first 2-3 months and then, monthly through the first year. Liver function and renal function tests should be performed at baseline and serum transaminases should be repeated after one month and then, quarterly. During follow-up, treatment should be discontinued if the leukocyte count is less than 3500-4000 cells/mm 3 . [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11]

| 1. |

Alsberg CL, Black OF. Contribution to the study of maize deterioration: Biochemical and toxicological investigations of Penicillium puberulum and Penicillium stoloniferum . Bull Burl Anim Ind. US Dept Agr 1913;270:1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

CellCept R TGA Approved Product Information 31 st January 2001.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Allison AC, Engui EM. Mycophenolate mofetil and its mechanisms of action. Immunopharmacology 2000;47:85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Carr SF, Papp E, Wu JC, Natsumeda Y. Characterization of human type 1 and type 2 IMP dehydrogenases. J Biol Chem 1993;268:272-86.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Schiff MH, Goldblum R, Rees MM. New DMARD. Mycophenolate mofetil (Myco-M) effectively treats rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients for one year. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:89.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Sliverman KJE, Pomeianz MK, Pak G, Washenik K, Schupack JL. Rediscovering mycophenolic acid: A review of its mechanism, side effects and potential uses. J Am Acad Dermatol1997;37:445.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Mehling A, Grabbe S, Voskort M, Schwarz T, Luger TA, Beissert S. Mycophenolate mofetil impairs the maturation and function of murine dendritic cells. J Immunol 2000;165:2374.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Nousari HC, Grant JA. Immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory drugs. In : Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in general medicine. 5 th ed. Philadephia: McGrawHill; 1999. p. 2860.

th ed. Philadephia: McGrawHill; 1999. p. 2860.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Hoffman-La Roche Inc. Cellcept (Mycophenolate mofetil) Product Information: 1995.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Bullingham RE, Nicholls AJ, Kamm BR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil. Clin Pharmacokinet 1998;34:429.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Perlis C, Pan TD, McDonald CJ. Cytotoxic agents. In : Wolverton S, editor. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy. 2 nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. p. 197-217.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Assmann T, Ruzicka T. New immunosuppressive drugs in dermatology (mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus): Unapproved uses, dosages or indications. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:505.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Product Monograph. Myofortic� (mycophenolate sodium). Novartis Pharma: USA; February 2004.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

European Mycophenolate Mofetil Study Group. Placebo-controlled study of mycophenolate mofetil combined with cyclosporine and corticosteroids for prevention of acute rejection. Lancet 1995;345:1321.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Non-steroidal immunosuppressive drugs. In : Khopkar U, Pande S, Nischal KC. Hand book of Dermatological Drug Therapy. 1 st ed. New Delhi: Elsevier Publication: 2007. p. 127-38.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Jones EL, Epinette WW, Hackney VC, Menendez L, Frost P. Treatment of psoriasis with oral mycophenolic acid. J Invest Dermatol 1975;65:537.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Tong DW, Walder BK. Widespread plaque psoriasis responsive to mycophenolate mofetil. Australas J Dermatol 1999;40:135.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Haufs MG, Beissert S, Grabbe S, Schutte B, Luger TA. Psoriasis vulgaris treated successfully with mycophenolate mofetil. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:179.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Geilen CC, Tebbe B, Garcia Bartels C, Krengel S, Orfanos CE. Successful treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis with mycophenolate mofetil. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:1101.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Grundmann-Kollmann M, Mooser G, Schraeder P, Zollner T, Kaskel P, Ochsendorf F, et al . Treatment of chronic plaque-stage psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:835.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Mimouni D, Anhalt GJ, Cummins DL, Kouba DJ, Thorne JE, Nousary HC. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:739.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Nousari HC, Griffin WA, Anhalt GJ. Successful therapy for bullous pemphigoid with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:497.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Williams JV, Marks JG Jr, Billingsley EM. Use of mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:506.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Megahed M, Schmiedeberg S, Becker J, Ruzicka T. Treatment of cicatricial pemphigoid with mycophenolate mofetil as a steroid-sparing agent. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:256.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Farley-Li J, Mancini AJ. Treatment of linear IgA bullous dermatosis of childhood with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1121.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Kowalzick L, Suckow S, Ziegler H, Waldmann T, P φnnighaus J, Glδser V. Mycophenolate Mofetil in Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Dermatology 2003;207:332.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Grundmann-Kollmann M, Kaufmann R, Zollner TM. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with mycophenolate mofetil. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:351.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Thomson MA, Stewart DG, Lewis HM. Chronic actinic dermatitis treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:784.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Chan TM, Li FK, Tang CS, Wong RW, Fang GX, Ji YL, et al. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. N Eng J Med 2000;343:1156.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Vassso S, Thumboo J, Fong KY. Refractory immune thrombocytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus: Response to mycophenolate mofetil. Lupus 2003;12:630-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Jose J, Paulose BK, Vasuki Z, Danda D. Mycophenolate mofetil in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Med Sci 2005;59:353.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Bijl M, Horst G, Bootsma H, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents a clinical relapse in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus at risk. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:534.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Schanz S, Ulmer A, Rassner G, Fierlbeck G. Successful treatment of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus with mycophenolate mofetil. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:174.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Goyal S, Nousari HC. Treatment of resistant discoid lupus Erythematosus of the palms and soles with mycoplenolate mofetil. J Am Acd Dermatol 2001;45:142.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Ann-Kathrin T, Michael M. Mycophenolate mofetil for dermatomyositis. Dermatology 2001;202:341.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Liossis SN, Bounas A, Andonopoulos AP. Mycophenolate mofetil as first-line treatment improves clinically evident early scleroderma lung disease. Rheumatology 2006 45:1005.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Daina E, Schieppati A, Remuzzi G. Mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of Takayasu arteritis: Report of three cases. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:422.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Russell JP, Gibson LE. Primary cutaneous small vessel vasculitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Frieling, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, Luger T, Beissert S. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acd Dermatol 2003;49:1063.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Tursen U, Api H, Kaya T, Ikizoglu G. Treatment of lichen planopilaris with mycophenolate mofetil. Dermatol Online J 2004;10:24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Nousari HC, Lynch W, Anhalt GJ, Petri M. The effectiveness of mycophenolate mofetil in refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:1509.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Enk AH, Knop J. Treatment of relapsing idiopathic nodular panniculitis (Pfeiffer-Weber-Christian disease) with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:508.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Davis MD, Rogers RS 3rd, Pittelkow MR. Recurrent erythema multiforme/Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: Response to mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1547.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Kouba DJ, Mimouni D, Rencic A, Nousari HC. Mycophenolate mofetil may serve as a steroid-sparing agent for sarcoidosis. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:147.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Shahar E, Bergman R, Guttman-Yassky E, Pollack S. Treatment of severe chronic idiopathic urticaria with oral mycophenolate mofetil in patients not responding to antihistamines and/or corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:1224.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

14,011

PDF downloads

5,666